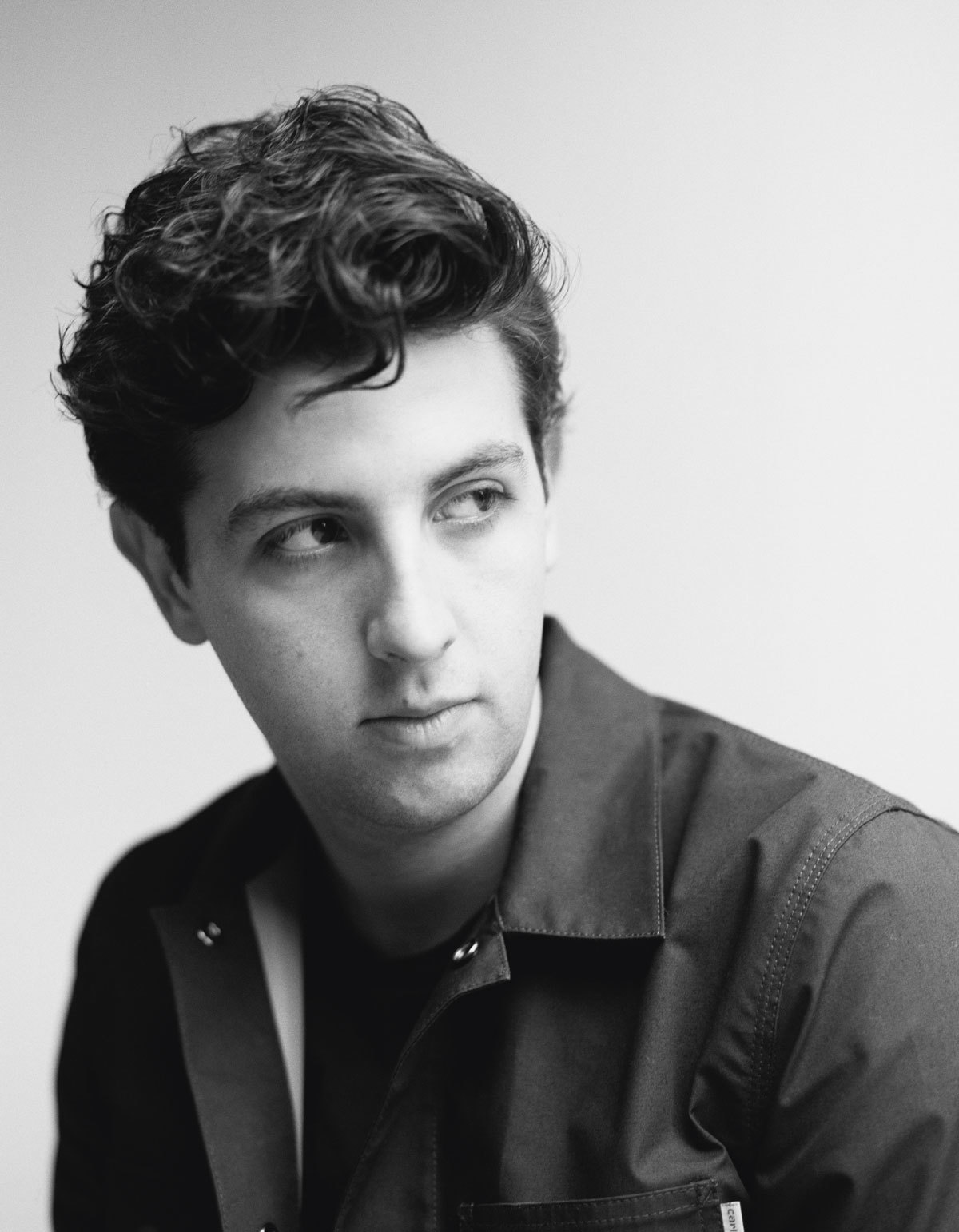

In March 2014, Jamie xx dropped two songs into the ether, quietly actualizing another gratifying curve to his thrilling young musical portfolio. Might this shy South Londoner now be adding solo stardom onto a CV that already cuts at wild right angles against his introverted manner? Of all his peers, Jamie crafted the sound that stretched furthest into the commercial corners of the world. It wasn’t meant to be like this. He didn’t even mean it to happen.

The content of the songs gave subtle clues as to why a solo record may be a natural moonlight from Jamie’s three strand day-job as part of the quietly wonderful pop trio the xx, a remixer of discerning taste and distinction, and global DJ draw. The first, Sleep Sound, was a direct descendant of his work with the xx, ramped mere inches away from their naturally melancholic, queer state into something that would correlate correctly on his version of the dance-floor. You earn a smile from Jamie. I get one when I ask if his special skill is to fashion music at an unusual default axis between the sinister and the warm. “That’s it, really,” he says. The second song, Girl, was another matter entirely. Opening with the pure, sampled invocation ‘You’re the most beautiful girl in Hackney, you know?’ and then building a dewy slow jam around a sample from the old Freeez classic, I.O.U (‘I want your love, give me your love, girl‘), it’s the closest Jamie has got to scripting a tripped out, straight up, post-club love song. In its unaffected beauty it sounded like the one song that might be delivered from the boy in the Palace T-shirt to the girl he couldn’t quite mutter the words ‘I love you’ to and instead chose to do it on a mixtape. Jamie, however, isn’t to be drawn on who the most beautiful girl in Hackney is. “I can’t tell you.” He will say that the Freeez sample was easy to attain because it was owned by his parent record label, The Beggars Group, and that the track set a new wheel in motion for his brilliant adventures in sound.

Somewhere around Girl’s release, Jamie stopped being in denial and conceded that, yes, his work alone, outside of the xx was probably turning into a solo album. He suits a solitary state and says all the time he spends in his studio is alone, without even an engineer, driving himself mad waiting for something to happen. “Even when I started making Girl, which was probably three years ago, I did think about making my own album. But I didn’t think I’d be able to do it with the time and effort it takes.” Constraints were piling on after the global success of the xx, which came as a surprise to all of them and which they wore with an appealing lack of guile. “I had this idea of making a mixtape and putting it out for free. But really I was just kidding myself to be able to make enough music for it and then I would focus on turning it into an album. Basically, it’s about not overthinking it. Which I would have done if I’d thought about making an album from scratch.” His work methodology is hard and simple. He tries and tries and tries until he gets something he adjudicates to be right. He used to make his best music, he says, on airplanes, where there was no distraction. Now he buries himself away in solitude. “I do send myself mad,” he confesses.

Jamie is part of a noticeable subset of clever, sedentary and un-showy young men that invert their generation’s need to broadcast every thought and word. Their privacy has made them all the more recognisable. You might see this man standing politely at the counter at Phonica or Kristina Records. They are fastidiously careful online music snoopers who build DJ sets with the strict sensuality and perfectionism of conducting a complicated orchestral recital. They emerged in the mid 00s as a direct counterpoint to the beer-soaked, drug-addled, money strewn superstar DJ, shaking at Ibiza airport in a Hawaiian shirt that had owned dance music for more than a decade and started to look like dance music’s embarrassing dad and treated DJing with all the crazed jubilance of a National Lottery win. This new British dance music boy is not chemically averse but still manages to maintain an interesting stance at the opposite of mindless hedonism. They have a special skill for self-flagellation. Jamie’s great duality is that he is a virtuoso DJ and producer who doesn’t think he’s much cop. “There are occasionally sets that I’m really happy with. More often than not, I’m just waiting for one of those really good ones.” This unique tension plays out as a clean, discreetly hopeful underscore to his music. His type have more of the disposition and spirit of The Hacienda before ecstasy than after and a similar broadside eclecticism when it comes to aggregating and mixing up genres. These are DJs and musicians interested in a place beyond the podium and the mirror-ball that like nothing more than a blackened room and every available detail of the equipment’s barcodes. They sound to me like they make music for girls who have gone to nightclubs on the night their world fell apart. 20 years ago, music journalists would’ve broken their backs finding a genre name for these new archetypes of young manhood but the nearest we’ve got in this snarky age is ‘Blubstep’, a horrible dismissive that deliberately infantilises real men’s real musical sensitivities.

Jamie’s early nightlife virginity was lost at Mass in Brixton and he found his Mecca at the recently shut down Plastic People, hearing his early hero, Four Tet play. For Jamie, nightclubs were not necessarily, sometimes not even, social spaces. “For me, it used to be simply music. I would enjoy it more if I was on my own.” For an older generation of nightclub people, who witnessed first-hand the come-together commonality and delirious positivism of Britain’s emerging dance music heroes back in the 80s, this is an astonishing admission. Was there no self-consciousness going to what is ostensibly a social space to be alone? “Yeah, there was sometimes. But if I was in a place like Plastic then it’s fine. It’s kind of more enjoyable to be on your own because you can’t really chat to anybody anyway. It’s just dark and loud.”

This is simply part of Jamie’s make-up. It’s how he likes it. When he first discovered and thrilled to the possibilities of dance music, he wasn’t even the boy at the counter in the record shop. “No, I never really did that sort of thing. Because… I’m not great at interacting with people.” The irony of his now facilitating so much crystalline night-time energy is not lost on him. He loves the idea of giving pleasure for a living. “To be able to play music that you love and see other people enjoy it might be the best job in the world, really.”

Success always looked like it would be a vulgar anathema to Jamie’s consummately new night-time contingent, paving a more reflective, less obviously celebratory tangent path into the twilight. They were moody not by design but instinct. Yet they have become the inheritors of a very old tradition of British musicians, incubated at the Independent labels under Daniel Miller, Tony Wilson and The BEF, fascinated by the rigorous possibilities of shadowy humanity and technology colliding. Of everything I learnt about Jamie in a lovely December afternoon with him that started in a Peckham living room and wound up in a taxi ride to the top of Cambridge Heath Road, the most telling was a story about his uncle who worked as a DJ at the Sheffield outpost of Kiss FM in the 90s, part of the tail-end of the last generation of Super-everything DJs. Their offspring didn’t want that aggrandised baton handing down to them. “I used to go to the radio station and he’d give me records. He played dance music. He tried to make me do a radio show. But I wouldn’t speak on air.”

The internet serviced him more fortuitously and Jamie was part of the original Boiler Room boys that gifted bespoke, sophisticated DJ services into the home via the laptop. “I started when it started, basically. When it was actually in a boiler room. It was just four dudes hanging out in a cold room next to Hackney Downs station, where Platform magazine used to be. It was pretty cool. I just used to go down and hang out and listen to other DJs.” At 17, he made his broadcast debut. “I was on maybe the fifth or sixth Boiler Room.”

If he wasn’t going looking for it, success was clearly going to find him. When recording the astonishing first xx record, a long player that may yet turn out to be as important to a generation as Blue Lines, Technique or Club Classics Vol.I was to their parents’, the head of Jamie’s label, Richard Russell would stop by the studio often. Russell is just old enough to predate the stadium house generation that corrupted something of the purity from the lean and judicious British dance music tradition from which the Phonica boys broke rank. Charging up XL Records in the early days he was part of a continuum, the signatory of faceless early breakbeat, progressive and techno 12″s that moved the disco conversation sensationally and awkwardly into the pop charts. By the time Britpop came along, it was almost as if characters such as Russell were the only ones looking forward rather than back, setting up nicely a 21st century in which the traditional rock band has become historic anathema and where urban music, once more, sets the fiery pace of futurism. (Jamie’s favorite XL record is Roy Davis Jr’s Gabriel, a spine-tingling ghost track that still sounds as if it were fashioned on another, more heavenly planet).

Jamie likes Richard. “For some reason I find it easy to talk to him,” he says. “I suppose that’s why he’s so good at his job and has built up the best independent record label in the world.” Russell was producing a revival album for canonised street poet Gil Scott Heron, I’m Not Here, at the same time the xx were making their first record. “He said it was inspiring to him.” The succession of events that happened after that to turn Jamie into a global radio name were nothing short of astonishing.

A Gil Scott Heron remix album, We’re New Here, he fashioned on the back of the xx tour bus (“just to keep myself busy while I was homesick”) picked up more acclaim than the original. Rihanna, then the biggest pop star in the world, borrowed a drop from the xx’s Intro for Drunk on Love, the opening cut from her world-beating Talk That Talk album. Then Drake, the most gifted rapper of his age, took the track from Jamie’s mix of Gil’s Take Care, with its familiarly close sounding timpani and soft pad rhythmic charms and turned it into the dominant pop hit of year at the end of 2011.

This was not the world Jamie had signed up for. “It was weird,” he says. He liked Drake himself. “He’s so nice. He’s a great dude and really talented. Everybody, his producer and everyone were so nice.” The machinery around him was less to his taste. “It’s more like that world, where [industry] people can sort of do what they want, it’s not really him but management and people around him, that’s what everybody thinks the music industry is like. Luckily I’ve been out of that because XL and Young Turks are the nicest people in the world. That whole thing was very weird. I felt a little bit guilty about it and I didn’t really get a choice in the matter. I was very happy that he wanted to use it and he really loved it, ever since I played him the original.” In a haunting twist in this tale, Gil Scott Heron died six months before Drake refashioned him into the surprising sound of now. “So at the same time, it was extra special to me because it had Gil on it and it was so very recent to Gil passing away. So I didn’t want it to become just a big pop song.”

Having Russell around him has helped incubate Jamie through the astonishing places his tiny yet astronomical skill for music has taken him. “A big part of what inspires us is having all of this around us. So much has changed since we were just a touring-in-pubs-band to when we were at XL and getting to meet other artists and to listen to other music via them. It’s completely changed us. The music wouldn’t be what it is without it all.”

For Jamie, the British history of dance music is a sacred, canonised space, a history he doesn’t think he intuits as well as he does. He doesn’t think it is too wild a prospect to describe a faith in the transubstantiative power of a dancefloor as a kind of modern belief system. “No, I don’t think it is at all. The worrying thing is that the more you go out to try and get that, the less it happens. I don’t know. I think that that’s true. I hope it’s not.”

Jamie xx dropped the third track that confirmed, yes, he was ready to become a solo artist in the summer of last year. All Under One Roof Raving represented an apogee of his talents, a spacious, daringly episodic bass track dotted with careful crowd samples from old raves that attempted to run a timeline through British club culture and perhaps even to point to its future. “I have a nostalgic view about the progression of dance music, especially in the UK. It fascinates me. That’s why I made that track. It’s such a rich history that’s sort of overlooked by everybody who’s not into club music. But it’s such a big part of people’s lives, even if they don’t really think about it.”

For Jamie, it is everything. The idea for All Under One Roof Raving was so simple yet somehow so big. “I guess it was that if you were in a club listening to it, the old guys would be nostalgic about the old times and the young guys would sort of be excited about new electronic music.” It found him another mass audience.

When we meet he is deep into the textures that will define the jamiexx.com xx record. Both his bandmates Romy and Oli will appear on Jamie xx’s album because, well, he says they have to. “I don’t think I could make my own album, because I owe so much to them, I couldn’t make one without them on it”‘ he says. “We all owe everything to each other.”

Credits

Text Paul Flynn

Photography Clare Shilland

Styling Max Clark

Photography Assistance Liam Hart