Last summer, Shoichi Aoki, the founder and editor of STREET magazine, uploaded 100 issues to its website, granting access to one of the most comprehensive archives of street style in existence.

“I had noticed that there weren’t enough photographers documenting street style in the world back then,” Shoichi told us of the magazine’s origins. “I did not know about Mr. Bill Cunningham at the time, but I knew that there was good street fashion in Paris and London.”

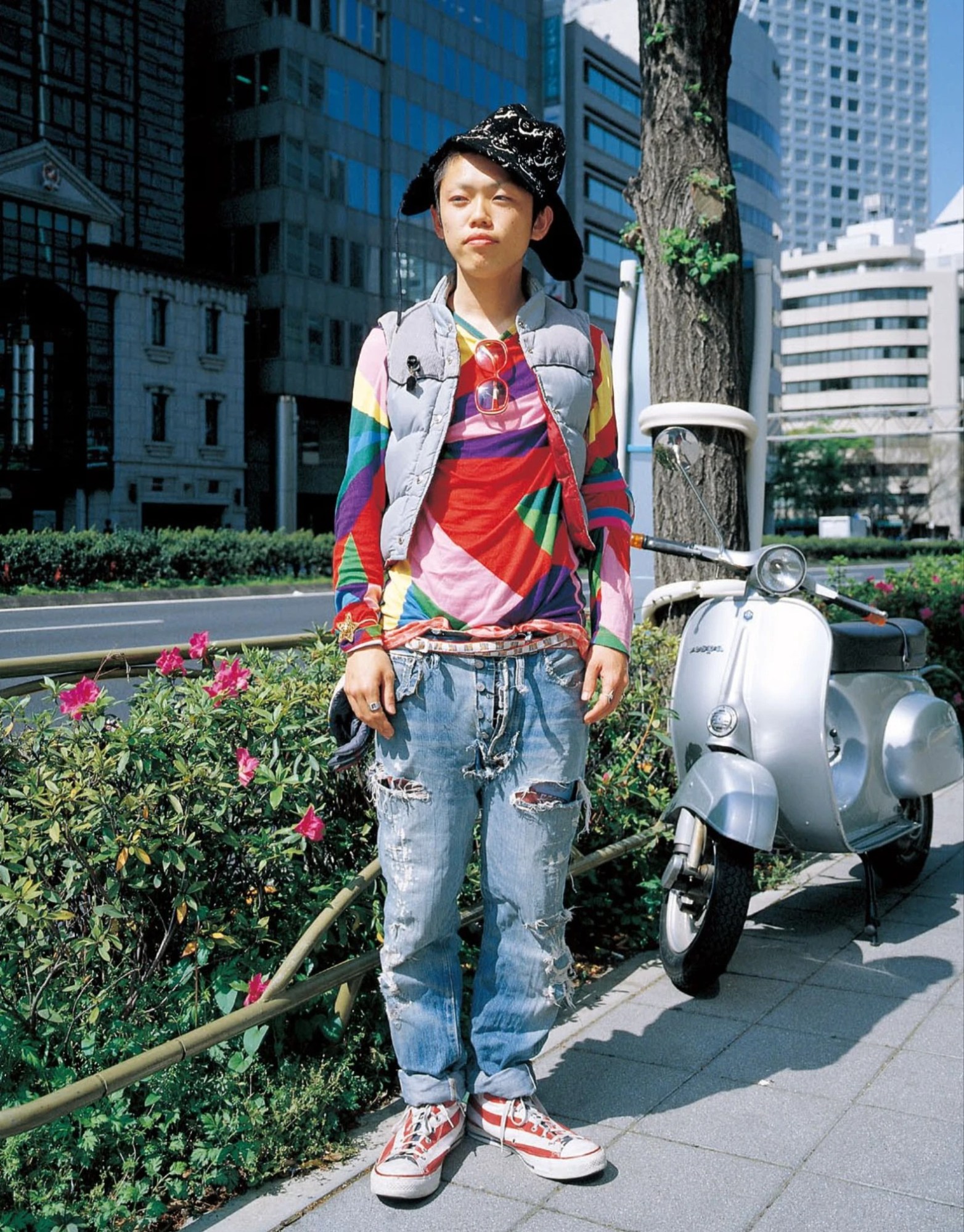

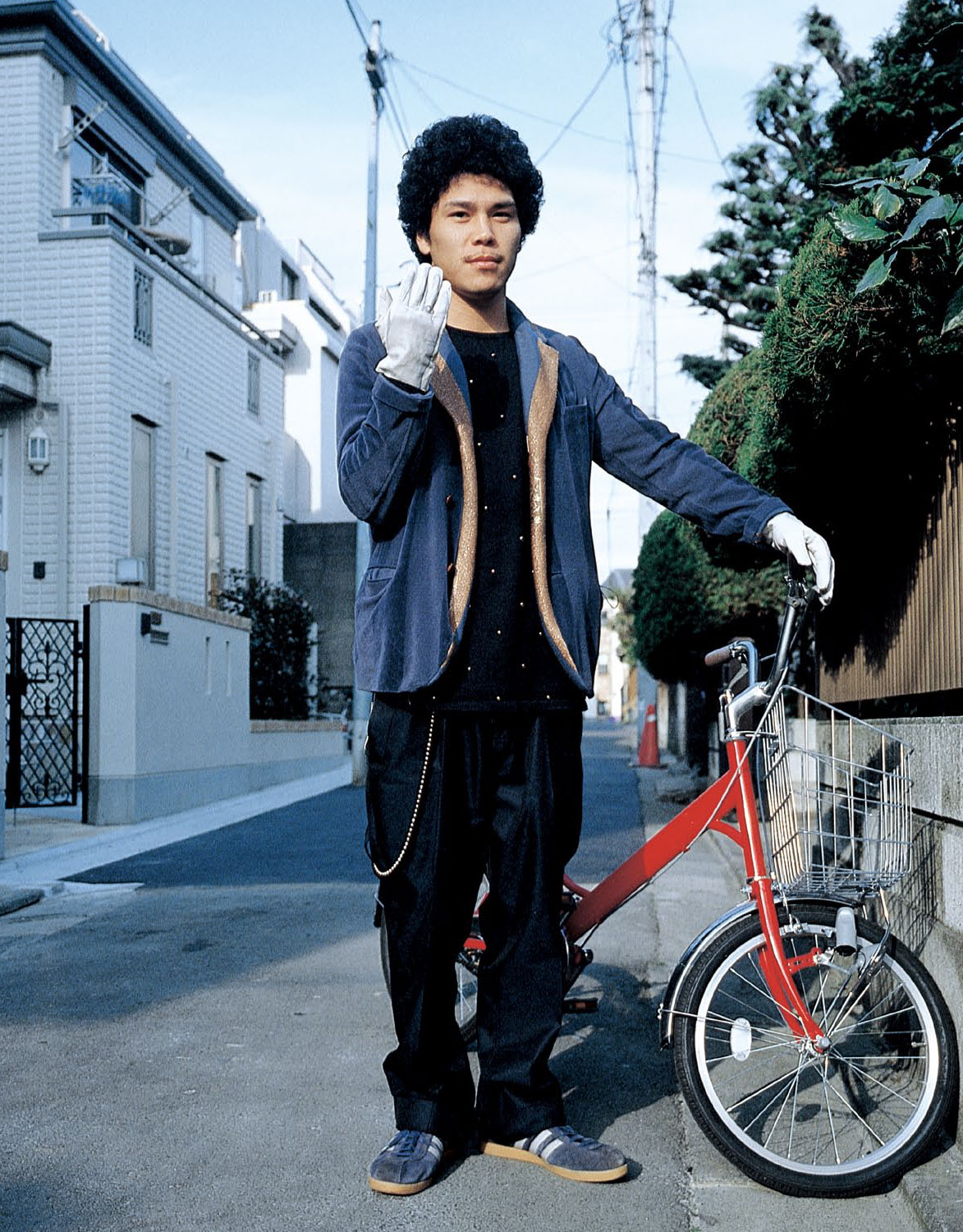

Following its success, Shoichi has now made the TUNE archive available, an offshoot magazine that focused on men’s street fashion in Harajuku between 2004 and 2015.

“For about 10 years, boys’ fashion in Harajuku was very creative,” Shoichi says. “So we began to publish the magazine TUNE to document that scene.”

Men’s fashion in Tokyo had lived through many different eras in the years preceding TUNE‘s birth. “The 80s was all about the crazy DC boom,” Shoichi says. The ‘DC boom’ (meaning ‘designer’ and ‘character’) is considered “the first fashion trend to originate from Japan instead of being based on imitations of overseas fashions”. Its proponents were the ‘Shinjinrui Generation’, an equivalent of Gen X, who were attempting to break away from boomers of Japan, whose style dominated the latter half of the 1970s.

“In the late 90s, things began to settle down, and brands that originated in London such as Vivienne Westwood and Christopher Nemeth became the centre of attention,” he says. It was here the Harajuku fashions that would become the backbone of FRUiTS magazine — Shiochi’s best-known title, that ran between 1997 and 2007 — were born. “Up until then, both men and women followed the same fashion trends. However, from around 1997, Harajuku boys’ fashion became all about Urahara-kei.”

Urahara-kei means fashion that came from Urahara, an area in the backstreets of Harajuku. “‘-kei’ has no direct translation, but in this context, its closest meaning is ‘style’.” Urahara-kei fashion is loosely defined by “T-shirts with characters and logos printed… American casual, hoodies with logos printed or embroidered, nylon blousons, thick denim items,” per the blog Just a Little Japanese. “It was heavily influenced by reggae culture, hip hop, and skater style.” Popular Urahara-kei brands included Neighbourhood, Undercover and A Bathing Ape.

“Some of the Urahara-kei brands started around 1990 but really became popular in the mid-90s,” Soichi says. “It was really interesting to see how things changed over those five years, but the end result was that all the boys in Harajuku were wearing Urahara-kei fashion. All of them!”

It wasn’t until the Urahara-kei style began to die out around 2003 that TUNE was born. “TUNE was the first to feature a new style that followed,” he says, “which was kick-started, in my opinion, by Cannabis, a shop on Cat Street, Tokyo. It was the complete opposite of Urahara-kei fashion. This new style came from experienced fashionistas.” Looking at these images you’ll see designer mixed with streetwear in a fashion we’ve since come to know as being synonymous with Tokyo.

“Then that fashion scene faded out and in 2015 TUNE stopped publishing. It’s been almost five years since then, and still no new fashion has emerged,” Shoichi finishes with. With 128 issues, documenting 10 years of fashion, there’s 10,752 pages of street style available in total. It’s available to buy in volumes of 10.

The digital eBook version of TUNE covers its entire publication run (No.001 – No.128) and totals 10,752 pages. Priced at $35.00 per set of 10, or $450.00 for the entire series, the eBooks can be downloaded directly from its shop.

Credits

All images courtesy Shoichi Aoki