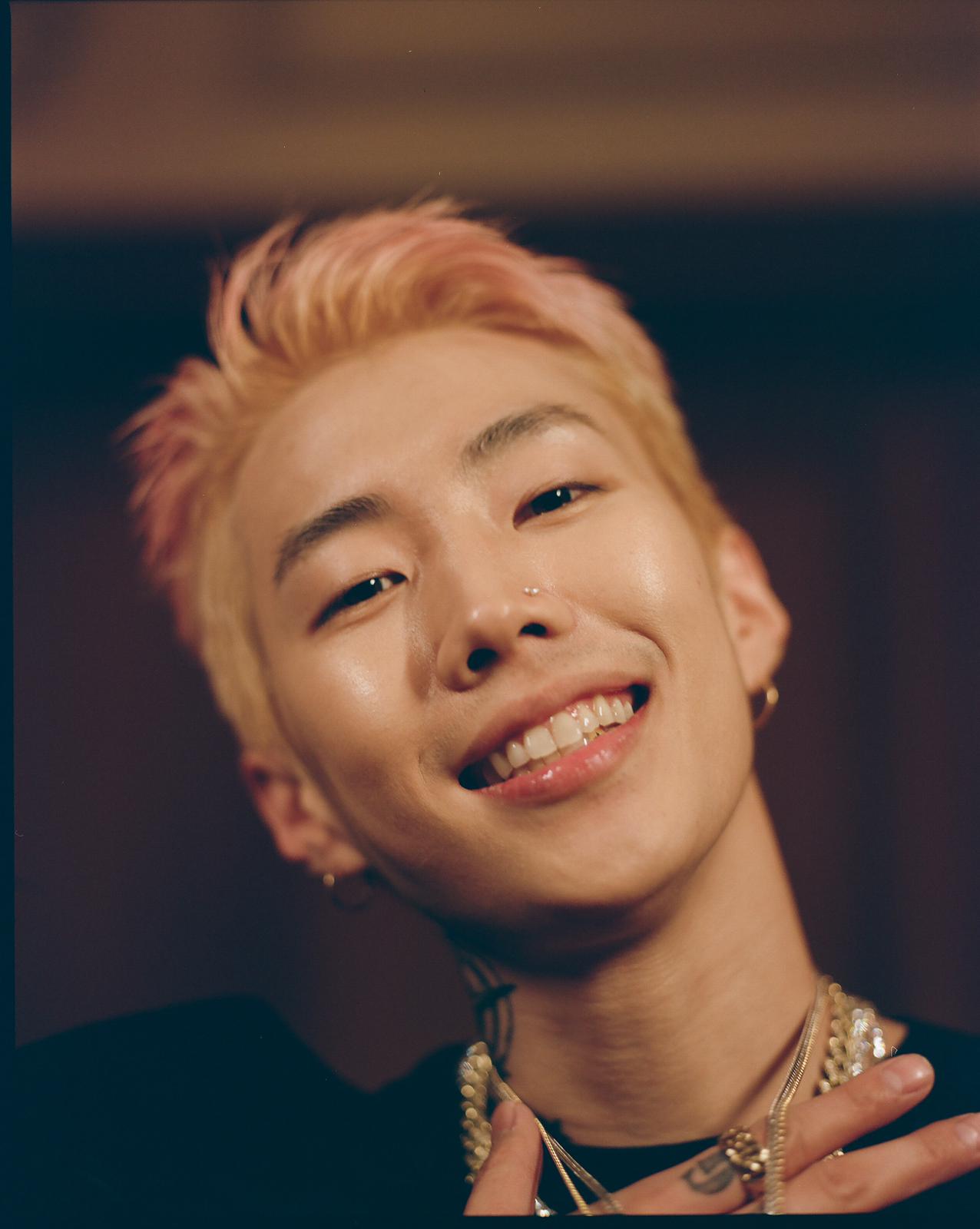

Jay Park is the first Asian-American artist to be signed to Roc Nation. He’s the CEO of independent Seoul-based record labels AOMG and H1ghr Music (both of which have shaped the narrative of hip-hop in South Korea over the past couple of years) and, across his five solo studio albums and four EPs, has built a legacy as one of the personalities responsible for propelling Korean hip-hop into the global spotlight.

It all started about a decade ago, when Jay (born Park Jae-beom, in Seattle) became the leader of newly-minted JYP-signed K-pop group 2PM and was sent spiralling on an upward trajectory. Exactly a year after the group’s debut, however, negative comments that he had made in English on his MySpace account – back in 2005, while he was still a trainee – were egregiously mistranslated and published by Korean media. In the fallout of the incident, where people all but demanded his departure from the group, Jay resigned from his position and returned to the United States. Since then he’s established himself as a multi-platinum selling international artist, scored a gig as a judge on Asia’s Got Talent and — as he tells us when we call him a few days after the release of his new This Wasn’t Supposed To Happen EP — has basically been “going where life takes me”.

Jay’s surprisingly soft voice melts through the receiver as he sits backstage in Miami, the latest stop on his well-named SEXY 4EVA Tour. “I don’t want to say that I’m not ignorant. I’m sure that I’m ignorant in some facet,” he says, reflecting on what would be his first of a few brushes with controversy. “Nobody knows everything. I just try to be the best human being that I can, to me and to other people. Do unto others as you want others to do to you — that’s the saying, right?” He owes his success, he says, to his own determination, luck, and a constant learning curve.

You see, Jay Park owns who he is. He remembers his mistakes. He counts his blessings. He realises how immense the weight of ‘being Jay Park’ can be, and he tries his best to live up to it constantly. “I like to move forward in life,” he says. “I don’t want to stay stagnant, because it’s not progressive. You made a mistake… what are you going to do to better yourself, your surroundings or the people around you? That’s always been my attitude.”

Genre is a fluvial concept for Jay: he’s given us sultry flows with Yuna on “Does She”, silken-smooth R&B on “Me Like Yuh”, and just the right amount of braggadocio on “K-Town”. The latter features on the singer’s This Wasn’t Supposed To Happen EP , which merges cutting satire with bouncy club anthems and sees Jay coming back stronger than ever. “It literally wasn’t planned,” he says of the collaboration with producer Hit-Boy — who has previously worked with the likes of Kanye, Jay-Z, Beyoncé, Kendrick, Selena and Drake — on the EP. “Just, with me being signed to Roc Nation and me being in the position that I am… it’s not every day you see an Asian hip-hop artist with a big producer like Hit-Boy, doing a project together.” Increasing representation is an adopted role that Jay is keenly aware of. In 2017, when he announced his signing to Roc Nation on Instagram, he described it as a win for “Asian-Americans… for the overlooked and under-appreciated.”

The signing came hand-in-hand with a wave of Korean artists finding their place within a global hip-hop context. While early Korean run-ins with hip-hop having been very blatantly influenced by the west, more recent associations with K-pop embraced the dialogue about authenticity. Bridging the gap between classic hip-hop flair and more localised elements, though, has always been precarious territory. Korean-American musicians like Jay Park then — who essentially fit both cultural moulds – have been instrumental in taking the genre global; a gargantuan task in itself, and one that gets very lonely, very quickly.

“I do feel like I belong though,” he assures us. “I feel like I’m a very daring person. I take a lot of risks. In Korea, I didn’t really know the culture. I was ignorant of how Koreans thought and how they spoke and what their thought process was like. I had never lived there before. There was a disconnect.” In the early years, Jay explains, he spent a lot of time feeling like an outsider. “Now when I come over to America, even if I’m at Roc Nation event, how many Asians do you think will be at that Roc Nation event?” He pauses. “Of course, they’re all very welcoming. They’ve been very supportive, very kind, but at the same time… I haven’t experienced what they have experienced, and they haven’t experienced what I’ve seen. Right there is the disconnect.”

As the reach of Asian hip-hop covers more ground globally by the year, so has the territory become more complex to navigate. It’s one thing trying to maintain authenticity, but at what point does it become a defence for cultural appropriation, something which Asian artists have often been called out for? Attributing it to the homogeneity of Asian countries or the relative infancy of the genre in the region — a more common argument used in the context of South Korea — is weak justification for handpicking “trends” without comprehending the cultural complexities and weight behind them.

At the start of this year, Jay himself faced backlash for defending US rapper Avatar Darko, who is white, after he was called out for sporting dreadlocks in a video. “I never tried to disrespect anybody and if I felt like I came at people wrongly, I definitely apologised,” he tells us by way of explanation. “There are always different perspectives — nobody can understand each other completely because we all have different experiences. At the same time, spewing hate towards each other is not going to educate anybody. It’s just a conversation that needs to be had.”

“K-pop artists in Korea or Asia [have] never lived in the States. They’ve never experienced the racism that goes on in the States. They’re not going to know why certain things are the way they are and why it’s insensitive,” Jay explains. “That’s for them to educate themselves, and for other people to as well. Hip-hop culture comes from the States, and if you really love it and all that it’s done for you, you should really take the time to study up on it and learn about it. Then you’ll have a better understanding of what’s insensitive and which lines you shouldn’t cross.”

Having long accepted the importance of leaving space in your life to make mistakes, Jay is sure to pass this message on to his artists. “You can tell somebody a thousand times that the stove is hot,” he tells us, “but if they haven’t felt it for themselves, they’re going to want to touch it.”

While Jay is quick to admit that he’s made a fair few mistakes of his own, he readily accepts them for the life lessons they bring. “If I didn’t make all those mistakes, I would never be here,” he muses. “Life gives you very valuable lessons. It depends on what you make those lessons into. You can take it and make it into gold or you can just look past it and think it’s nothing, think it’s garbage. It all depends on perspective, on what your attitude is.”

Jay Park’s This Isn’t Supposed To Happen EP is out now. Check it out here.