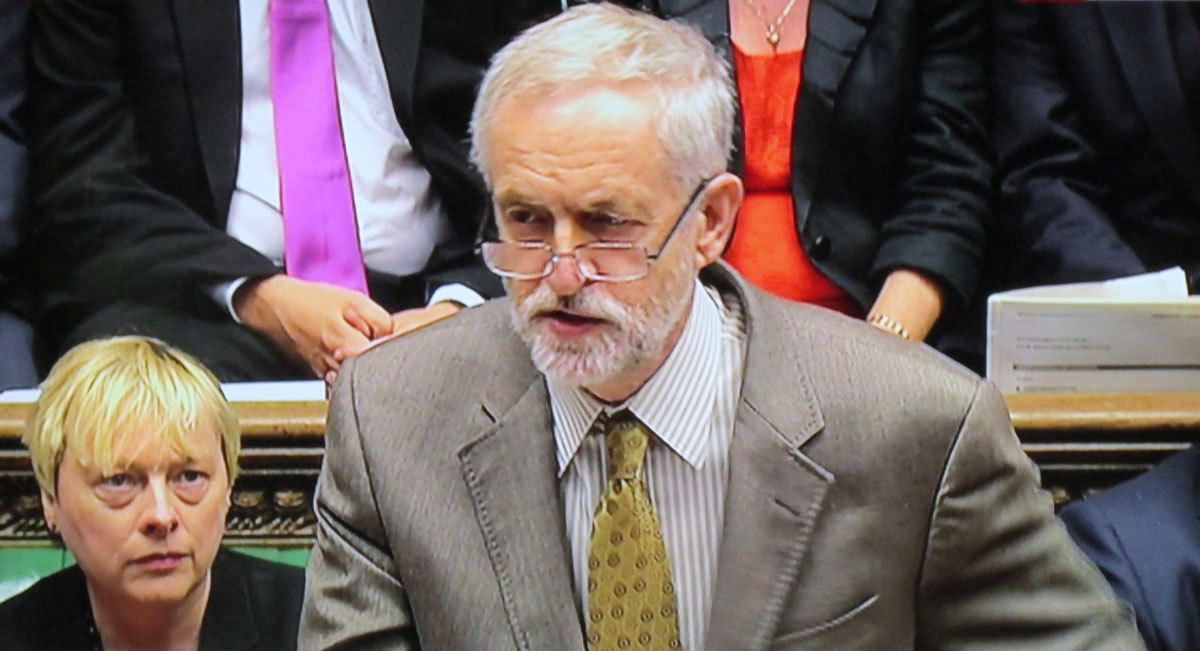

It started innocuously enough with the veteran MP — bearded, vegetarian, teetotal, Obi Wan Kenobi look-a-like — just limping over the line with the 35 signatures he needed from fellow MPs to get onto the Labour Party’s leadership ballot. It ended, gloriously, with him becoming the party’s most radical and left wing leader ever in living memory. In a few short months Jeremy Corbyn has gone from 200/1 outsider to win the Labour Leadership to running even with George Osborne and Boris Johnson to become the next Prime Minister. Elected to parliament during the 1983 General Election, Jeremy Corbyn is an overnight success 32 years in the making. It’s a victory that reignited politics and reinvigorated debate, and was completely unexpected.

Unless you live in his constituency of Islington North, and unless you are depressingly au fait with the left wing of the Labour Party, he probably passed you by until he managed to get onto Labour’s leadership ballot. Even then he barely scraped through the selection process, and was included only in the name of ‘widening the debate’, which makes his sudden rise all the more shocking and thrilling; it surprised everyone in the Labour Party that people are actually interested in having a wider debate.

History, it’s commonly said, ended in 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed. The old age of ideological politics was over. The final nails in its coffin where the elections of Tony Blair and Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1997, and the rise of The Third Way, a new, ideology-less ideology between socialism and capitalism that wanted to harness the best of both worlds, for a new, bright, shiny, material future. Western democracy and free market capitalism had won, we’d reached the highest of heights we would ever reach.

This all came crumbling down with the 2008 with the financial crash. The Third Way, which proclaimed the death of boom-and-bust economics, was shown be a mirage. The rise of Jeremy Corbyn can be seen as a direct result of the continued absence of a new solution for the problems that crisis evoked, and that those post-ideological politics had no answer for. Jeremy limped onto the ballot paper because fellow politicians didn’t realise there had been no adequate solution, he overwhelmingly won the public vote because the people did.

Much of the debate during the leadership election centred around his electability, and his possible relationship with a general public. It could go either two ways; he could be a left wing Nigel Farage, admired as an outsider by those who disdain the managerialism of the political class, and could be a figurehead of a popular movement for change; or he could be totally ignored and viewed as an anachronistic throwback to the ideologies we supposedly gave up on once and for all when Tony Blair was elected.

It’s ironic then, that a large portion of his supporters were born after the ideology he believes in apparently died, and have rejected the “new” politics that sprung up in its wake, which was meant to make life better for them. By simply being the only person offering a different solution, this old school beard-and-sandals lefty managed to become “down with the kids” without even trying; without wearing a baseball cap like William Hague, without threatening to hug a hoody like Cameron, without pretending to like the Arctic Monkeys like Gordon Brown, without playing a guitar and cuddling up to Noel Gallagher like Tony Blair.

Has he appealed to the young because he’s the only politician who actively seems to be listening, fronting people’s questions to Cameron in his first PMQs? Instead of learning responses by rote, in the platitudes of PR double-speak, he speaks like a human being with a sympathetic ear to the problems of people. Instead of chastising us as idiots or dreamers for imaging a fairer, more equal, less vicious society, he wants to help make that happen. He was the only candidate to campaign explicitly for protecting the weakest against the interests of the richest; of scrapping university fees, rent caps, clamping down on tax avoidance, renationalising energy companies and trains and industries, he appeals to peace and justice and kindness; he’s hardly Pol Pot in a pair of Birkenstocks.

We live in a world where everything’s rising — unemployment, rent, tuition fees, living costs, sea levels — except wages, which are still lower, in real terms, than they were before the 2008 crash. We’re the first generation to be worse off than our parents, and they’re a generation telling us that’s the only way it could be. A few short months ago there was no mainstream opposition to these policies, now, our opposition might actually oppose them.

Most importantly he resonates with the young because it’s the young who are finding it hardest to succeed at the moment, who are disproportionately affected by the government’s programme of cuts. The young are targeted because the government know they are both least likely to vote, and equally, least likely to vote Conservative. The young are also more likely to be idealistic, and Corbyn, if nothing else, represents that idealism; we’re young enough to dream of a better world, hungry enough to challenge the orthodoxy, and realistic enough to know things have to get better, because we can barely afford to live in London, can barely afford tuition fees, and can barely find decent jobs. The current government is now so right wing, that even one of its most right wing MPs, David Davis, has denounced its recent Trade Union legislation as being fascistic. Corbyn, amongst all the misery modern life subjects us to, is a ray of hope.

It was the young who were most adversely affected by the financial crisis, and who sprung up around the world in various grass-roots movements to protest against its effects; from Occupy to Uk Uncut, from Podemos in Spain, to Syriza in Greece. Loose coalitions of leftwing activists, hippies, anarchists, and academics who came together to form an alternative to a world that was suggesting there was none. Though they may not have directly succeeded, these movements’ ripples have now brought us Bernie Sanders in the US and Jeremy Corbyn here in the UK: these movements were born out of new, global networks created by social media, and whose leaders are old school, authentic and real.

It’s precisely Jeremy’s oldness that’s appealing to the young too; his un-coolness, his casualness, his aura of a man out of time, propelled to leadership — unlike every other suit-wearing Oxbridge mannequin in Parliament — by principle instead of desire for power. His sheer difference is enthralling for a generation who grew up under the spinning presidential shadow of Tony Blair, and the smooth, formless, authoritarianism of David Cameron.

Corbyn, conversely, is a man untouched by the apolitical chumminess of Blair’s Britpop and the technocratic elitism of Oxford PPE degrees and the shifting amorality of high office that sprung up in its wake. Corbyn is no career politician, and he’s untainted by Labour’s glory years in office. Paradoxically his refusal to ever change his principles gives him precisely the platform he needs to help the Labour Party change.

Can he actually become Prime Minister? No one gave him a chance of becoming even leader of the opposition, so it would be unwise to write him off. You might as well dare to dream. Yet it’s hard to tell the difference between the light at dawn and sunset, and it’s equally hard to predict whether Corbyn will herald in a brighter day or is merely the last golden rays of an older age.

Credits

Text Felix Petty