JH Engström never strays far from home. For the Swedish photographer, home is more of a state of mind than it is a physical place. His raw and autobiographical work is informed by a distinctly subjective approach, probing his sense of self within an existential framework. These numerous and nuanced investigations, more often than not, materialise in photo books through which JH explores the evaporating and frail condition of being human. “Editing a book is a combination of the experience of having done it many times before, intuition and letting go,” JH says. “All of my books demand different approaches. And one book always leads to another. They are all linked.”

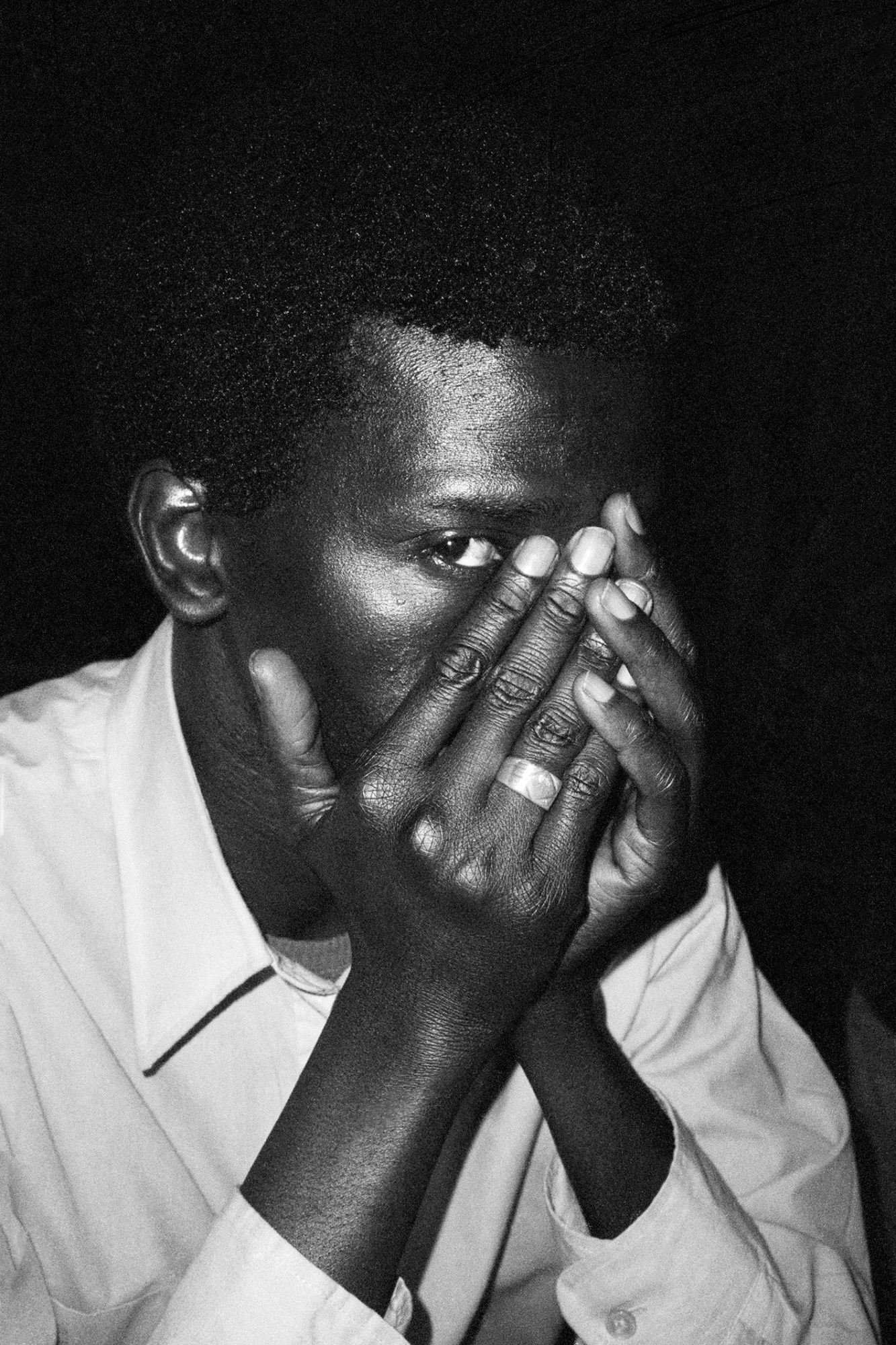

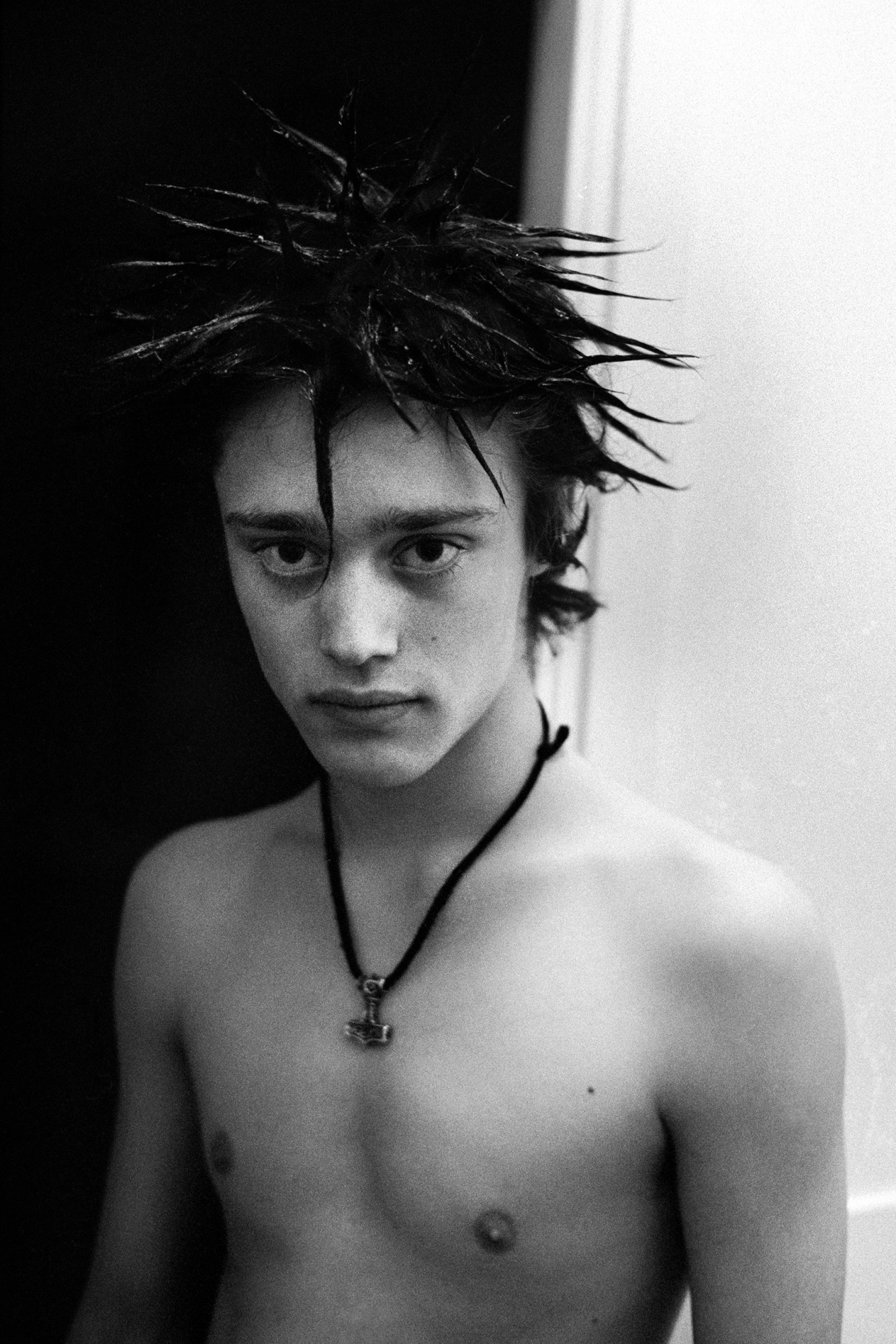

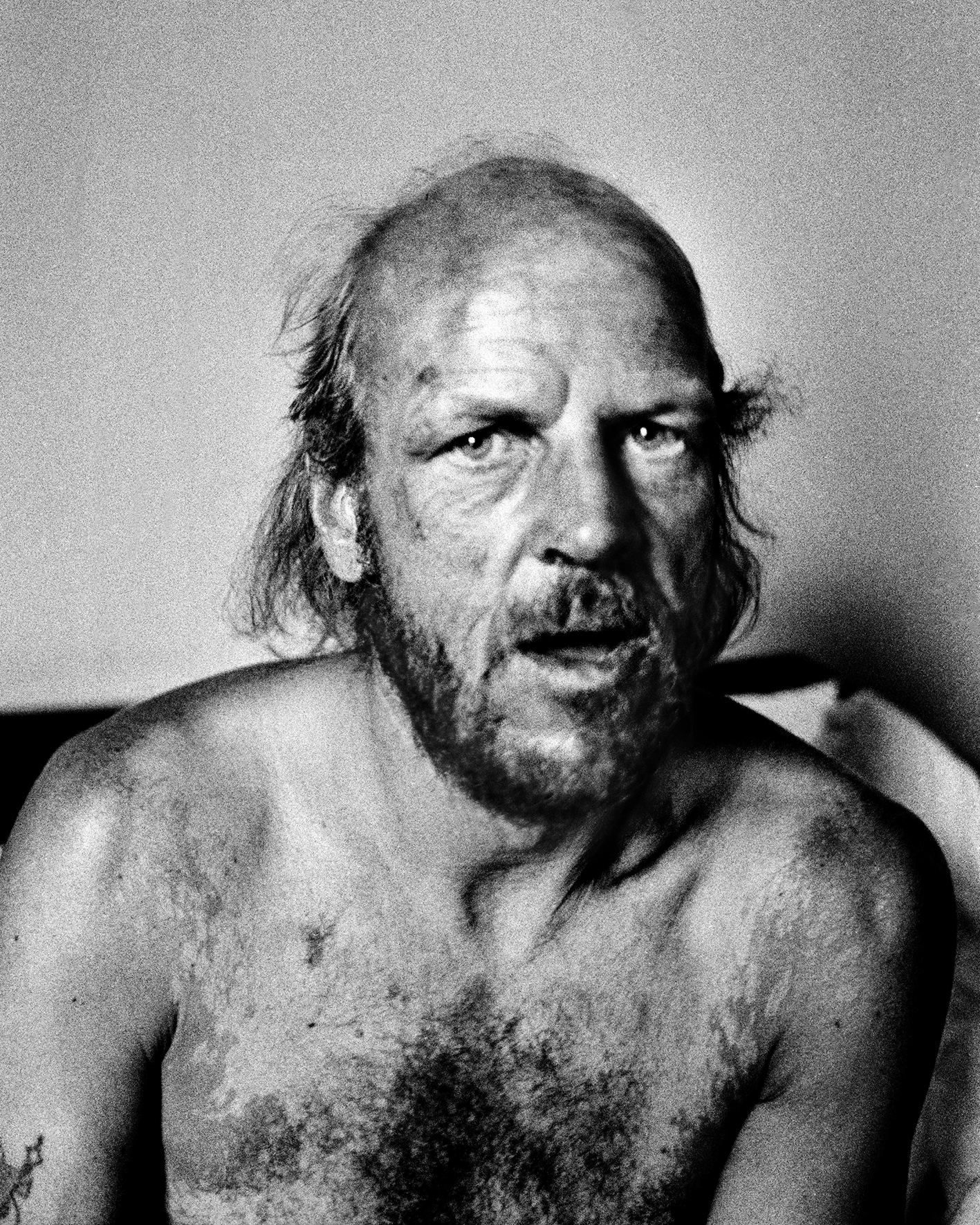

JH’s latest, The Frame, is a daunting black object that rests heavy in your hands. Inside, the Swede has orchestrated shots of ice-aged rocks from his hometown in Värmland alongside 30 years’ worth of photographs of men — trans and cis — and non-binary people. The faces we find are not those of warriors, conquerors or heroes but of fathers, brothers and sons. The book packs a tender punch, surveying the multivalent meanings of masculinity, rife with contradiction and complexity. JH’s point of view is the only thing that connects this disparate range of portraits, so it’s intense, confrontational and reliably existential. Here, we catch up with JH to talk about gender, time and home.

You once said that you seldom go somewhere to photograph but rather photograph because you are somewhere. Yet you have amassed an incredible archive of portraits of men. What have you been drawn to in them, even if subconsciously?

I photograph what I somehow identify with. Being a man myself, I naturally question what that even “means”. There are two levels here: the private and the collective. Of course, they coexist with one another. Definitions are complex. For me, definitions almost always end up with tonnes of questions. This whole book is basically a million questions. As I write on the back cover: “Within the frame of bodies, words and time, I see transience, questions and change…”

Who are the people in the book?

They are a mix of friends, acquaintances and passing encounters. My father is in there and my grandfather too. These are people who I have crossed paths with, and I never photographed them with the intention of making this specific book. Photographing, for me, is an intuitive, instinctive and even primitive act. There is no recipe. I believe all my work, in the end, can be summed up as one huge self-portrait. That’s the way I do art because that’s who I am. We don’t always get to choose these things. We are who we are.

I like how you have scattered self-portraits throughout the book in such a subtle and seamless way.

As I mentioned, I photograph that which I identify with, consciously or unconsciously, so placing myself in the book was a natural decision for me. Again, the private and the collective coexist. But where does that start and end? What are the frames? What are the borders?

This questioning of borderlines feels pertinent now, with definitions around gender and identity increasingly under scrutiny. How do you hope the book resonates?

I believe in the reader. The questions the book raises are existential, and I hope readers can enter them without any prejudices. If there’s one thing that I am allergic to, it’s when artists have the ambition to tell the reader what to think or feel. I would rather approach the subjects as questions instead of answers. What is gender? What is identity? What is masculinity? What is the father figure?

I find these questions very interesting. They are, of course, linked to society’s perceptions of things, movements and time. We are certainly witnessing a historical change and renegotiation regarding how we define and perceive gender…

The photographs of the ice-aged rocks which bookend The Frame really evoke the scale and passage of time.

These moraine rocks were pushed forward by the enormous forces of sheets during the ice age. This was around 10,000 years ago, and they have not moved since. To stand before and witness something that looks exactly the same as it did all those years ago is a stunning and surreal experience. So, these photographs led me to questions about time. And maybe time is the only frame we can be sure of in our lives.

They were taken in your hometown. Why is this sense of home important to your work?

I prefer working with what is close to me, on one level or another. Sometimes, I might not even know that I am connected to something until I feel the urge to photograph it. I photographed these rocks because they were there, right in front of me. They brought back many memories from childhood. I tend to think that being oneself is really being at home. That’s why home is important.

‘The Frame’ by JH Engström is published by Pierre von Kleist.

Credits

All images courtesy of JH Engström