By 1975, New York City was $11 billion dollars in debt. Teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, the city could no longer afford to maintain basic municipal services. Enraged about proposed budget cuts, unions representing the New York Police Department (NYPD) and the New York Fire Department (FDNY) created a pamphlet titled “Welcome to Fear City: A Survival Guide for Visitors to the City of New York,” which they passed out at local airports and hotels. On the cover, a black hooded skull smiled menacingly; inside were a list of nine “safety” tips for tourists such as “Stay off the streets after 6 P.M.” and “Remain in Manhattan.”

Unsuspecting recipients had no idea they were caught in a propaganda war waged against Mayor Abe Beame, who took the battle to court and secured a temporary restraining order to protect the “economic well-being of the city”. But the image of New York had already taken a nosedive as Hollywood and the media capitalised on the gritty glamour of a city struggling to survive.

Taking a page from the new wave of neo-realist Hollywood films, including The French Connection and The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3, the Fear City pamphlet cast New York as a den of sin, doomed but for the heroism of the boys in blue. Copaganda, as it is popularly known, is a long-standing American trope, one which found increasing popularity with the arrival of television in the 1950s with shows like Dragnet, Naked City and Peter Gunn.

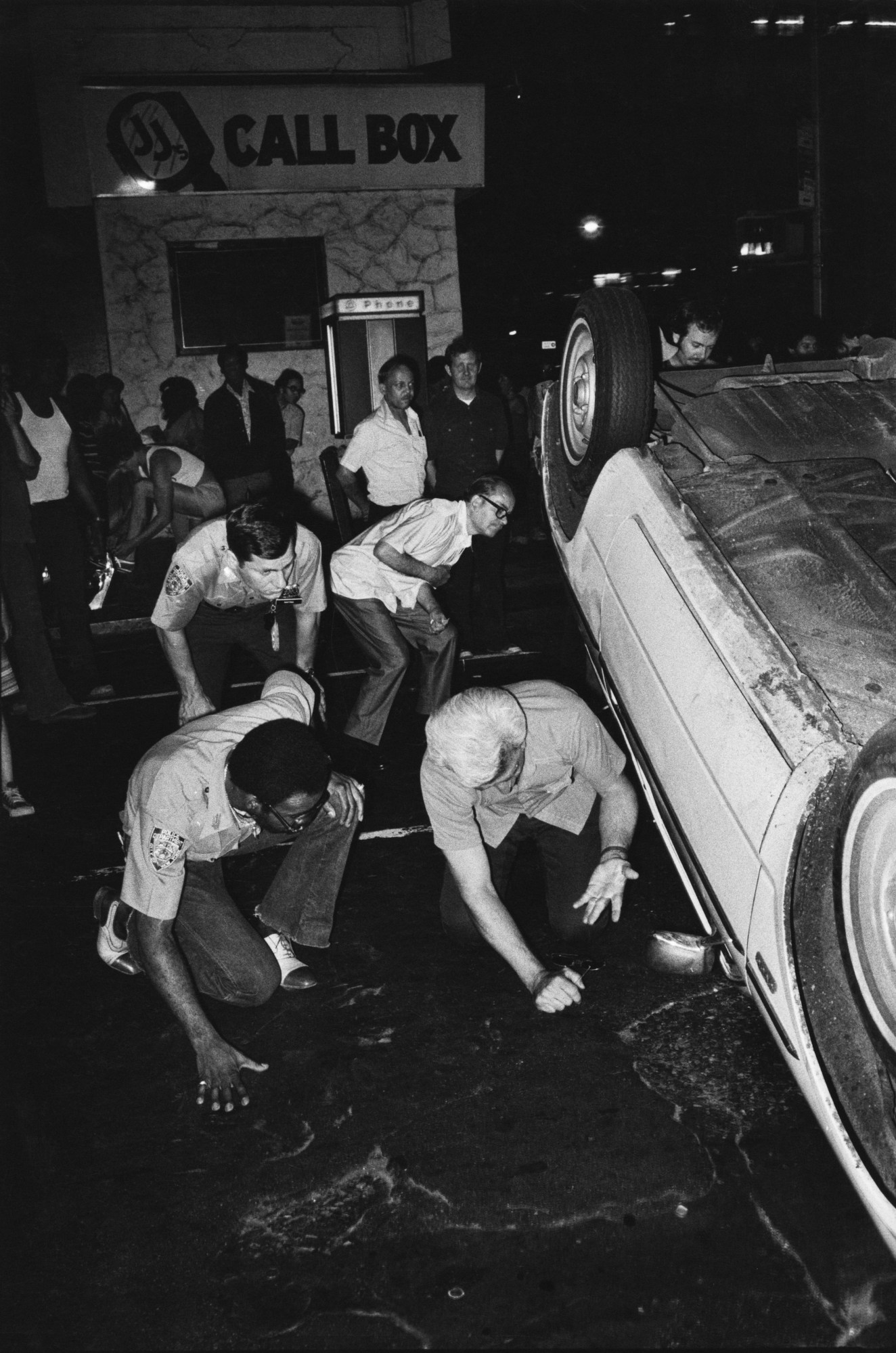

By the 1970s, copaganda was everywhere, slickly produced to package violence to the masses. American photographer Jill Freedman (1939–2019) was not impressed. “I hate the violence you see on TV and in the movies. I wanted to show it straight, violence without commercial interruption, sleazy and not so pretty without its make-up,” she wrote in the introduction to her 1982 monograph Street Cops, which is being republished and exhibited this month.

“Jill was a rebel until the day she died,” says her first cousin Marcia “Cookie” Schiffman, who, along with her daughters Susan Hecht and Nancy Schiffman Sklar, are trustees of the Jill Freedman Estate.

Hailing from Pittsburg, Jill arrived in New York City in 1964, where she worked as an advertising copywriter until the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Devastated, Jill joined the Poor People’s Campaign, where she lived among 3,000 people in Resurrection City, a shantytown built on the Washington Mall that stood for six weeks until the government tore it down.

In 1970, Jill published her first book, Old News: Resurrection City, which would be republished in 2017 as her last. In the book, she clearly sides with the people and against authority. “Jill hated policemen,” Nancy says. “When she was in Resurrection City, the cops were nasty and violent.”

Ever ready to challenge authority and breakthrough social and cultural norms, Jill was the last person one might expect to describe the police as “good guys”. But after completing her 1977 book Firemen, she decided to embark upon a four-year ride along with members of the NYPD to see for herself. “Cops are a hard brotherhood to break into,” Susan says. “Jill was one of the guys, and that’s what they loved about her.”

Given a front-row view of the action as it unfolded before her lens, Jill maintained a rare position for a woman photographer — a label she disdained. At a time when gendered titles were used to diminish and discriminate, Jill wanted to be known for her work and nothing else. Yet, she invariably ran afoul of sexism of the time. “Jill didn’t have a lot of filters; she said what was on her mind,” Susan says. “She spoke like a man and drank like a man. She did not tolerate stupidity. It was acceptable for a man to behave that way, but it was a real detriment for her.”

Jill continuously broke the mould, challenging gender norms in both her life and her work. She embraced aggression in women and vulnerability in men, centring those on the margins in her work. “Street Cops is about a job, being a cop,” she wrote inside the book. “The good ones are street smart, they know who’s who and what’s what. They see it all. I saw enough. What I learned with cops is there are really good guys, and the bad guys like to hurt people. Sometimes it’s better not to know too much. Sometimes it isn’t. This story wasn’t easy.”

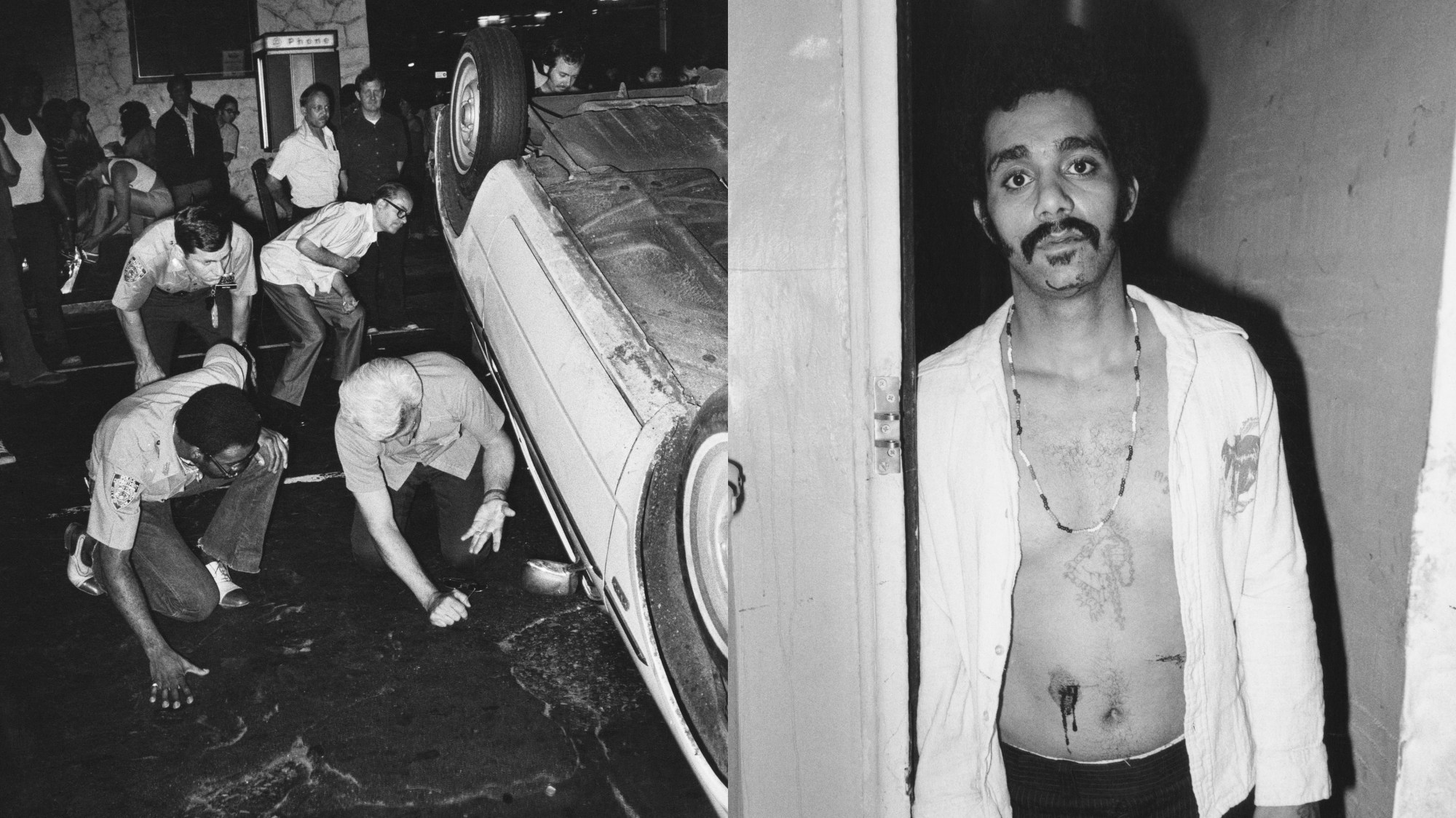

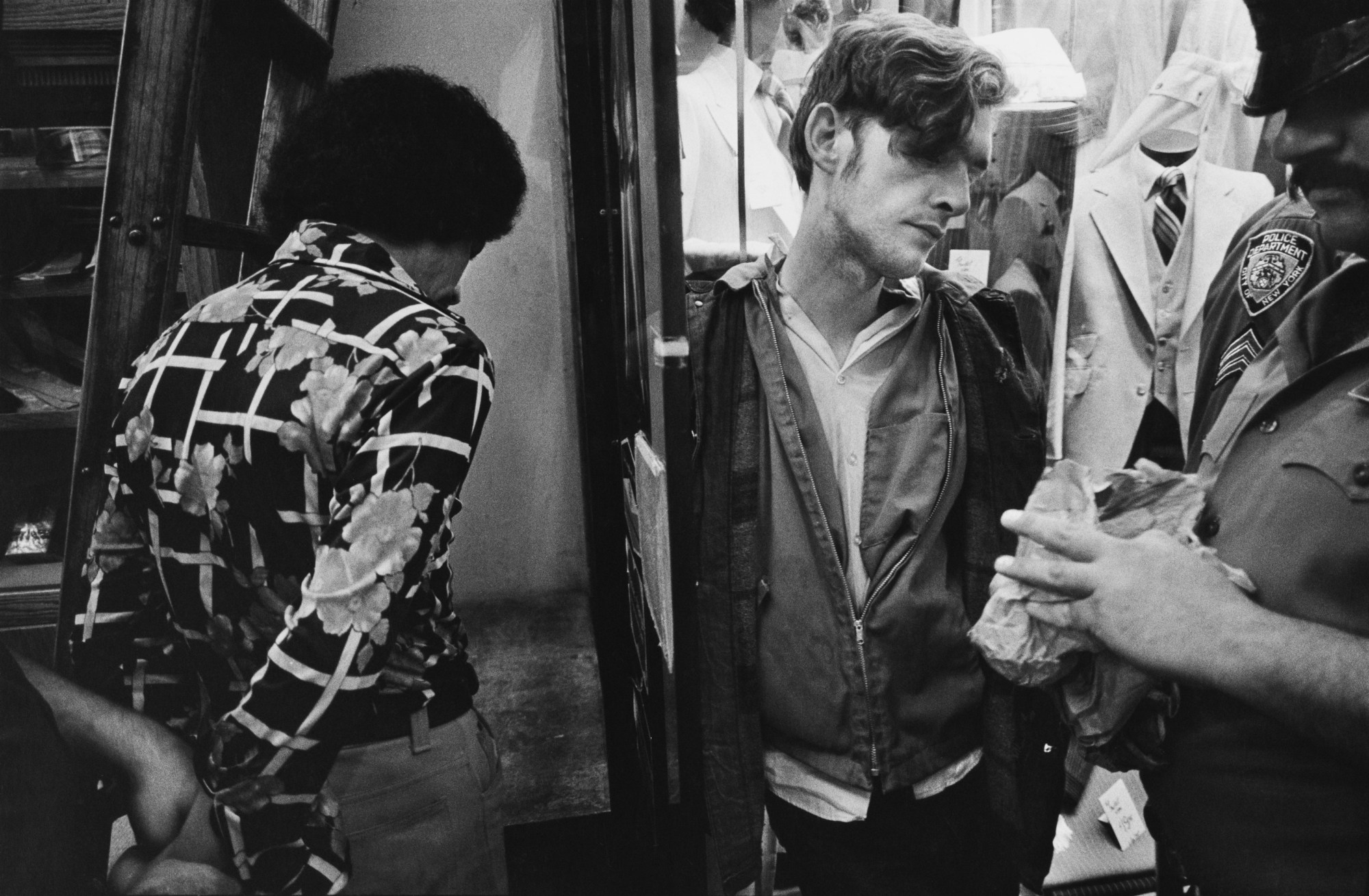

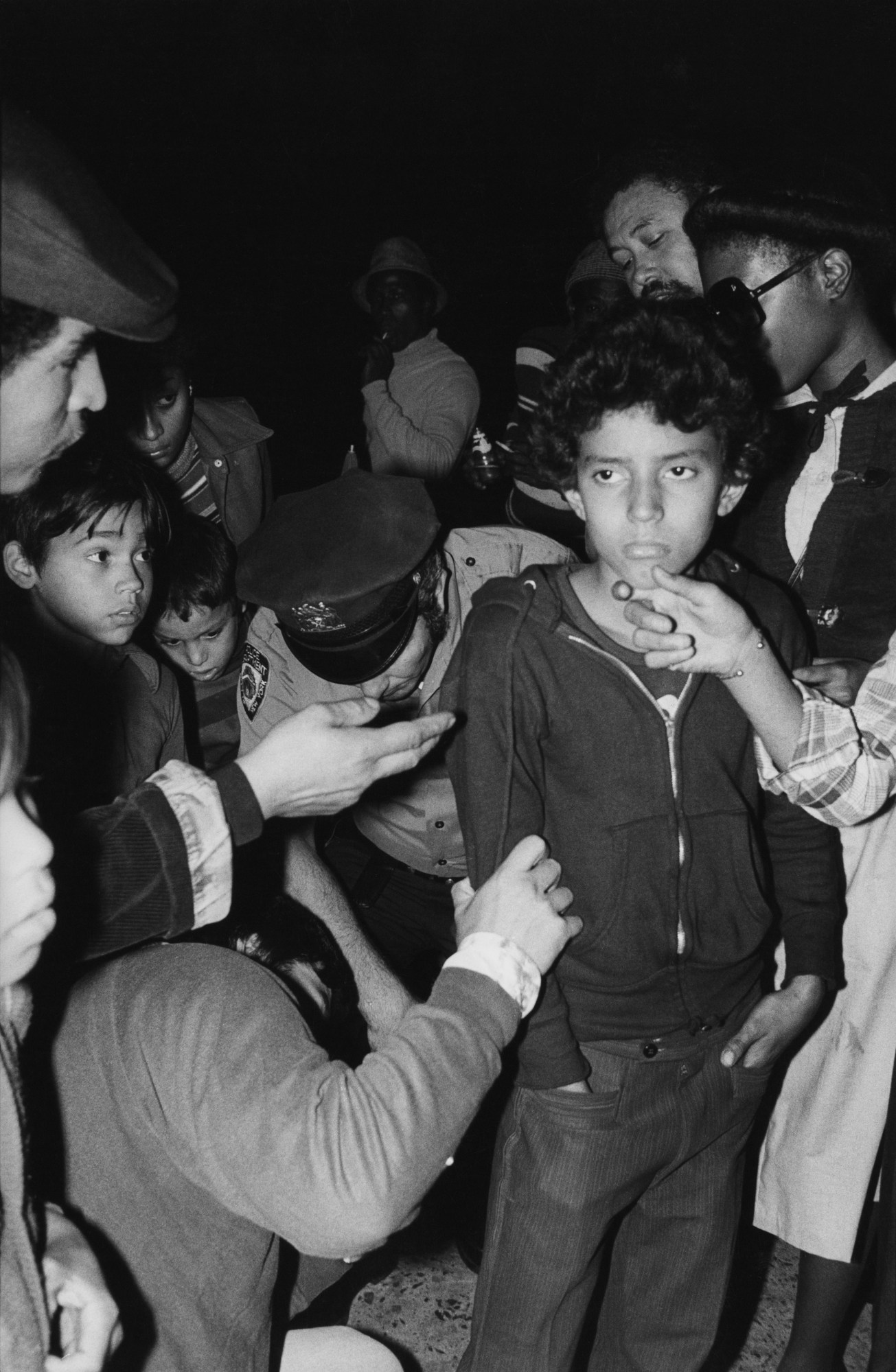

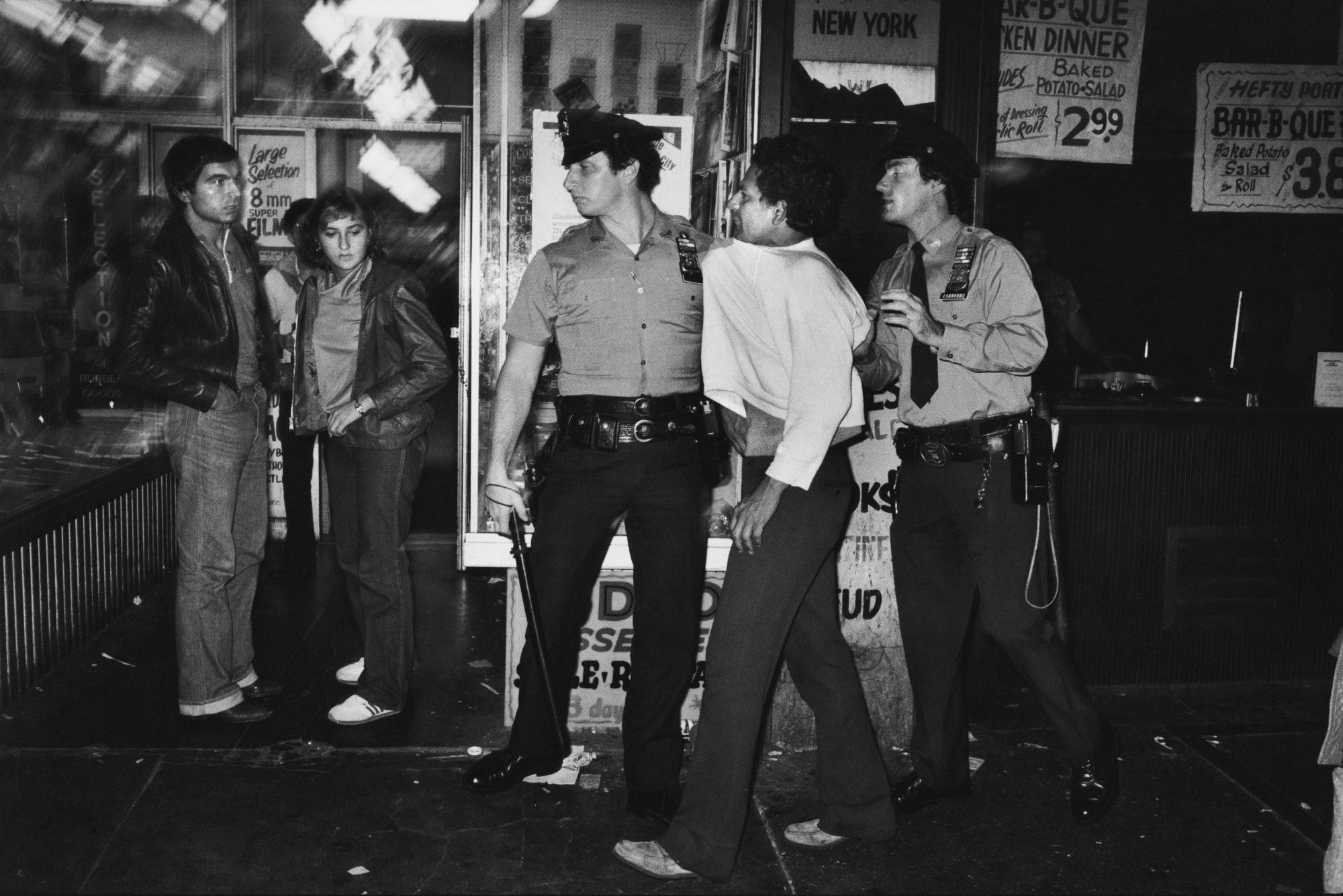

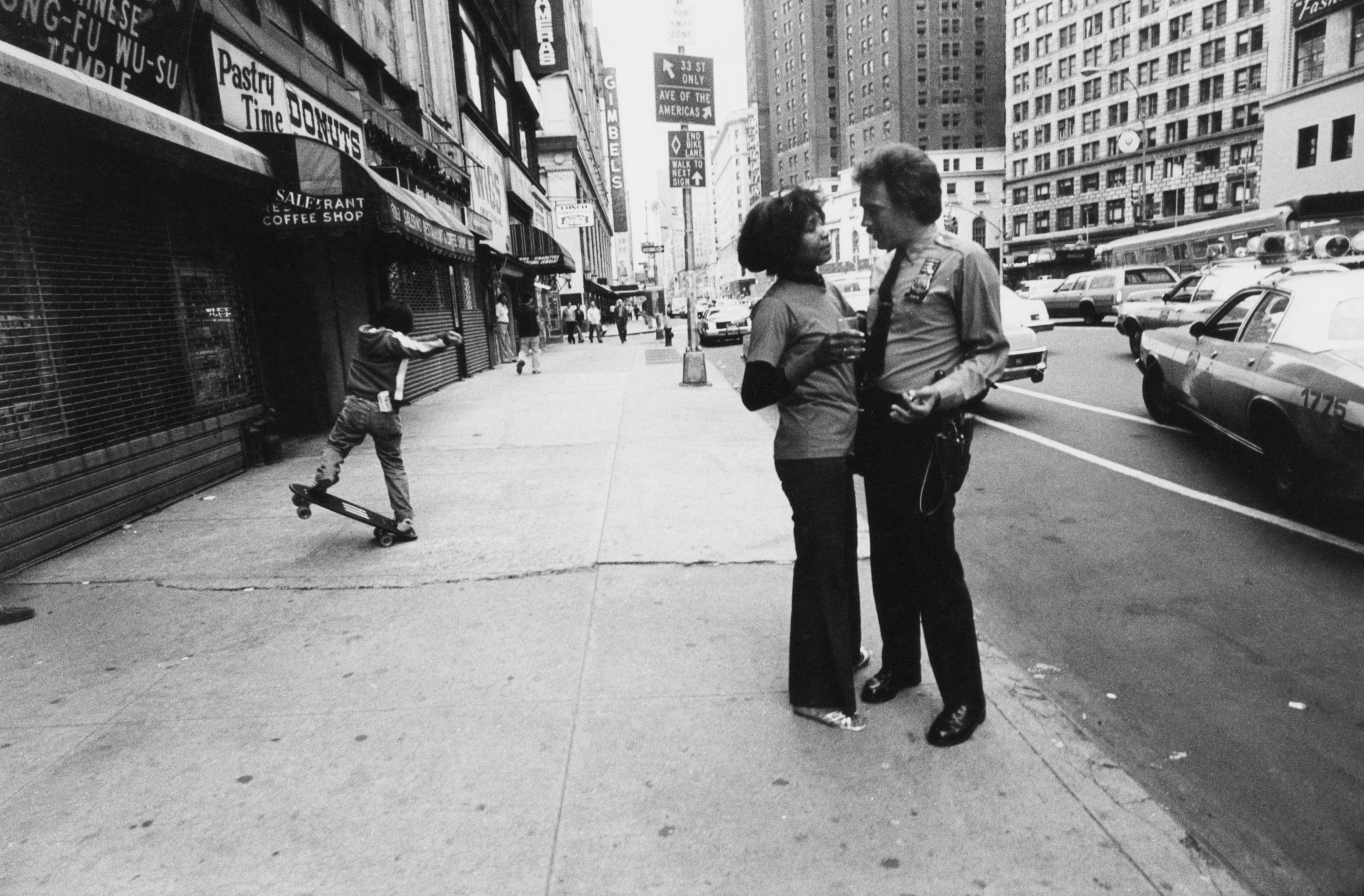

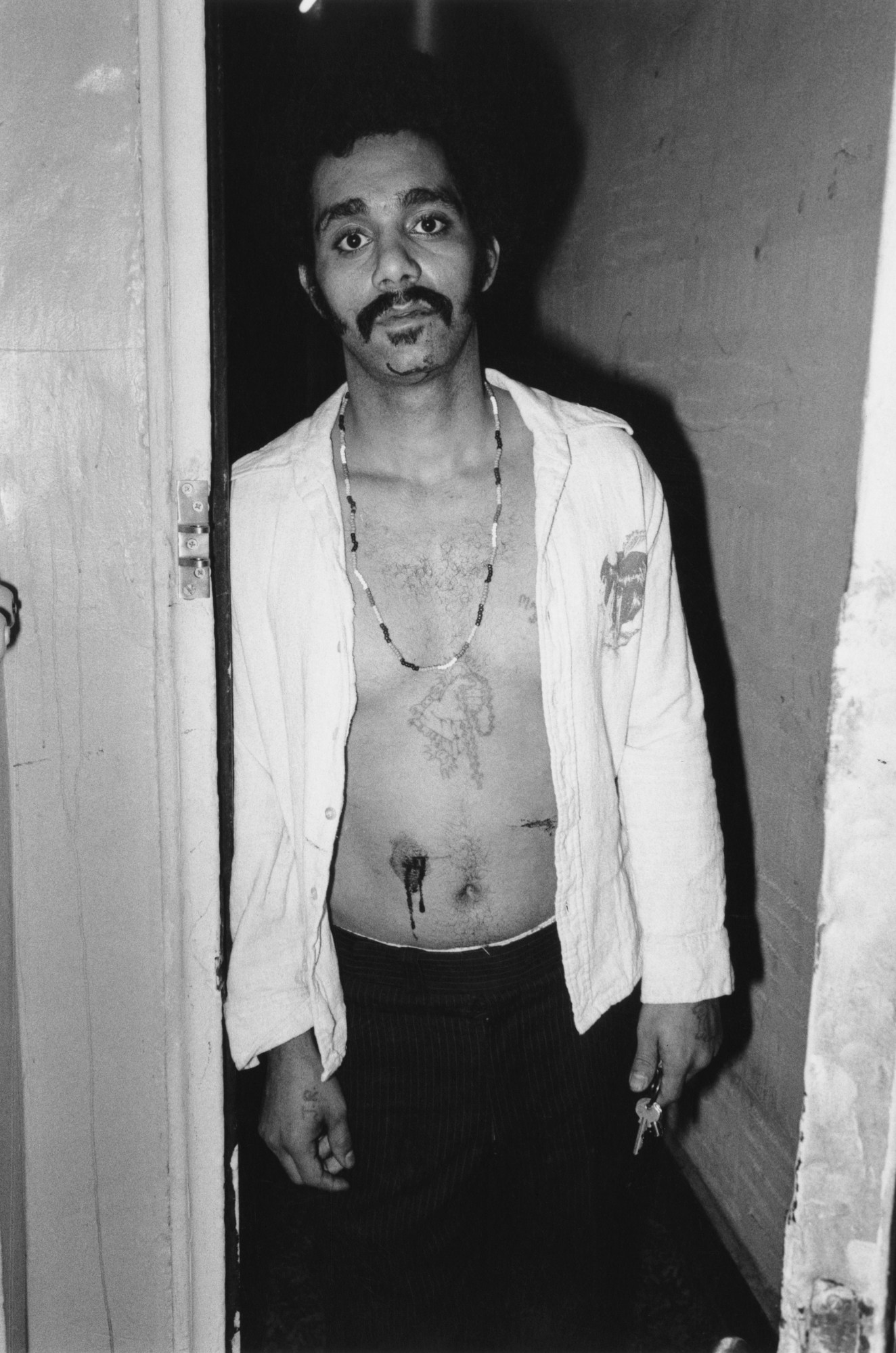

Offering a complicated albeit sympathetic portrait of NYPD, Jill embraces the “good guys vs. bad guys” paradigm that runs counter to the photographic evidence. The police are frequently seen treating white perpetrators with good humour and ease and sharing a laugh in the back of a cop car or at the station. Black and Latino perps, however, are seen being pushed against the wall, dragged down the stairs and slammed to the floor.

“The only thing that stands between you and the people out in the street is fear. If they don’t fear you, they don’t respect you. If they don’t respect you, you’re dead,” Jill quotes an unidentified police officer as saying, placing the text opposite a photograph of a white male cop and a Black man enjoying a moment of camaraderie.

In another spread, a white male undercover police officer straddles the chest of a Black teen boy and grips his right hand by the wrist. Opposite the photograph, Jill writes, “Street crime is the purest type of police work. All you’re doing is watching out for the bad guy.” Undoubtedly not every cop uses their position of power to perpetrate systemic abuse; some, as Jill reveals, actually take a stand. She recounts the story of a police officer devastated at the death of an infant, who was docked 15 days pay after punching a doctor who said, “Why’d you waste your time? It’s just a n******”. “That’s a cop. That’s a fuckin cop,” Jill raves.

Let inside an often impenetrable circle, one forged in the bonds of violence and death, Jill takes a deeply subjective stance. This isn’t “just the facts, ma’am” reportage. It’s a document of an era where the government abandoned the police and the citizens alike and left them to fend for themselves. The one thing everyone in the book seems to agree on is that nothing is promised, except the possibility there may be no tomorrow.

‘Jill Freedman: Street Cops 1978-1981’ is on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York, from 17 September – 30 October 2021. ‘Jill Freedman: Street Cops’ will be released by Setanta Books on 10 September.

Credits

All images © Jill Freedman Estate, Courtesy of Daniel Cooney Fine Art