When you flick through Jim Goldberg’s new photo book, you feel as if you’re peering into someone else’s private world, their relationships, their heartbreak, their pain. It’s a visual autobiography of sorts, intensely intimate, touching on the collapse of a marriage, the death of his parents, the birth of his child, and the rediscovery of love. Through his wildly imaginative lens, it’s a deeply moving portrait of his world, one that most people can relate to in some way.

The book, titled Coming and Going, opens with news of his dad’s cancer spreading, and Jim is unflinching in the way he presents it. “It is natural for me to document, and I’m not afraid to look at hard things,” he says. “It really is about stopping time and looking at my life.”

However, Jim insists he didn’t make Coming and Going in order to grieve. “There is grief for when one breaks up with somebody,” he says, for example, “but that’s not what my life is about. And nor do I only take pictures to get rid of pain.” He explains that there can be a privilege that comes with witnessing someone passing. When his dad died, Jim was there, and he remembers photographing him. “I remember, aside from the photography, the experience … felt like a real privilege, like being at a birth,” he says. “So with grief comes a privilege, and that privilege is to be present in life and to see its comings and goings.”

As a photographer, Jim is best known for giving a voice to the marginalised in books like Raised by Wolves (1995), his iconic work about homeless youth. But with Coming and Going, he is turning the camera on his family, on his story, and it wasn’t always easy. “It’s not as if I like to have my picture taken; it’s not as if I like seeing myself in a book,” he says. “I would also love to edit certain things out of my life, but I can’t.”

In the book, Jim shows his viewer forensic details of this family life. Like the collection of his daughter’s used toothbrushes (17 in total). Or the collected shavings of his hair as it goes increasingly grey over the years. “I should collect this,” he thought at the time, “because I know I’m gonna go greyer and greyer and greyer.” That relentlessness in capturing every detail of a story is present throughout. “I felt I needed to be as rigorous with my own life and my own process as I am when I photograph outside in the world. It’s also more about life than it is about something anthropological, sociological. I — or my life — is the subject.”

Another big subject is the passing of time, which Jim depicts in his uniquely fragmented way, using mundane objects and incidental snippets. There are the aforementioned toothbrushes and grey hair. He also shows knotted cables that clog a corner of a room and piles of sweets on the floor, each with a label naming whose is whose pile. As time passes, the family’s private spaces change and evolve, leaving poetic traces of the people.

You suspect Jim couldn’t make this kind of work without being a compulsive collector or even just someone who saves seemingly meaningless items. “I also live with a person who saves things, so we have to be really careful that we don’t save too much,” he says. It means that organising and editing becomes an essential part of his process. He has a table that’s nearly 20 feet long on which he lays out various piles. “There might be a pile of pictures of my daughter or pictures of dogs, and then there might be piles of letters or found materials. And so I’ll go through them, and then I’ll make smaller piles.”

There’s a fearlessness in the way he presents these fragments. He’s not afraid of ‘mistakes’ – smudges, scratches, scribbles of text and paint. He’s not afraid of defacing photos or scrawling sentences across their surface. And that trademark rough-around-the-edges style feels fittingly human here. “Perhaps the smudges come from the fact that I’m sloppy, but it also might come from the fact that it feels more real to me. I’ve also always tried to raise more questions than to give answers.”

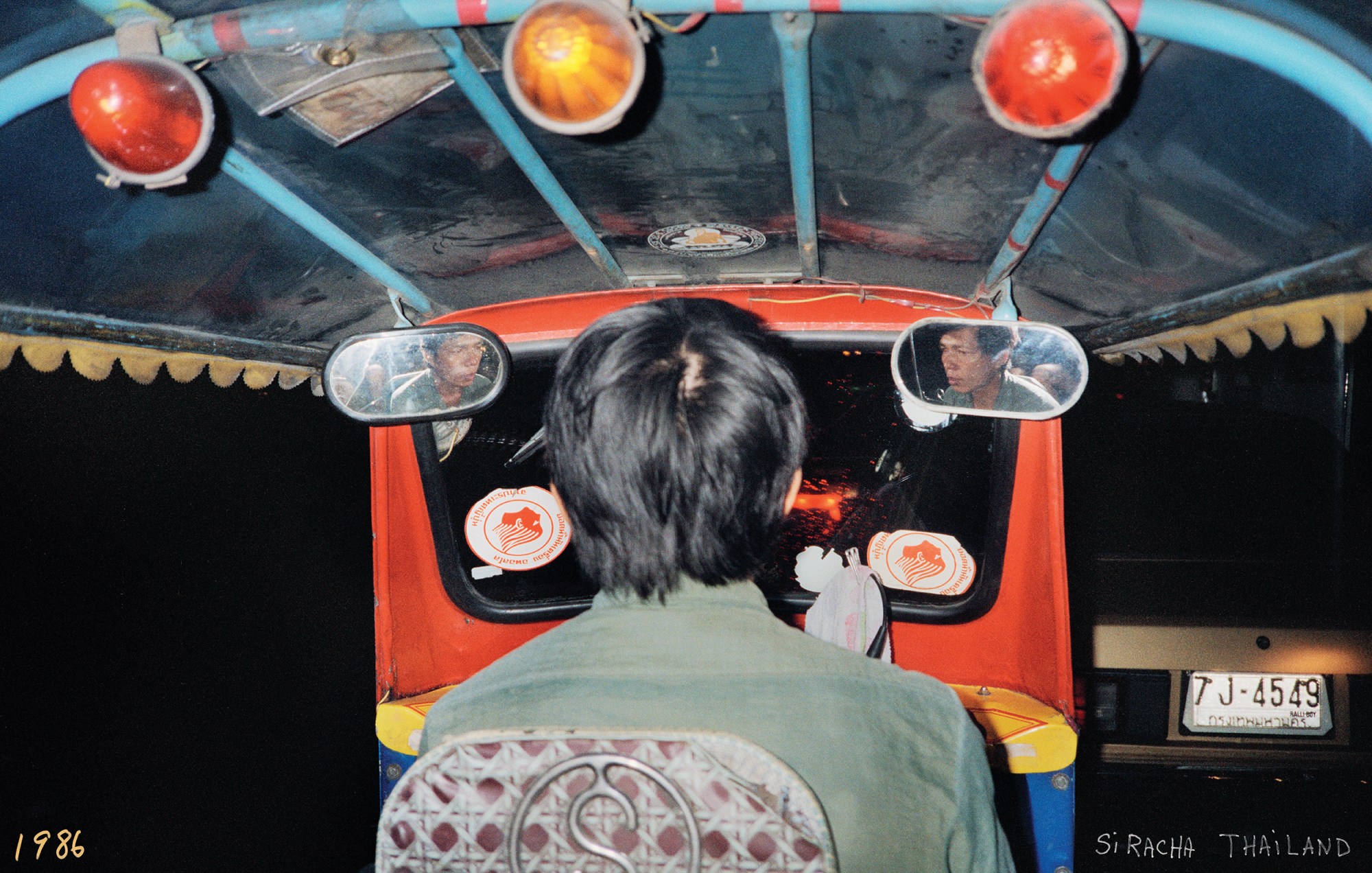

For this work, Jim used many different kinds of cameras and different types of art materials, and in his fusion of mixed media, he creates a kind of collage that evokes flickers of memories that come in and out of focus. “I like that there’s a hybridisation within my work of taking all these things and combining them,” he says. “I love the idea of many images coming together; there are layers on top of layers. And those layers then become a way for people to experience it.”

Jim has created an original visual language over the years that goes beyond mere photos laid out neatly in a book. There’s a compelling chaos to it that most photographers would shy away from. It can be messy and complex, much like life, but it’s always threaded together with compassion and curiosity for the world around him. “Maybe I’m just a frustrated painter,” he says of this singular way of seeing the world, which feels like a sort of kaleidoscopic unravelling of his experiences. “I think that’s kind of how life is, too. It’s all coming at us all the time. And if I can make a little bit of sense out of it, I feel like I’ve done my job.”

‘Coming and Going’ (2023) by Jim Goldberg published by MACK Books

Credits

All images courtesy of Jim Goldberg