Shoes. Treacherously long fingernails. Flowers as hats. Egg cups as hats. Eloise. Lena Dunham. At first, the objects and people in Joana Avillez’s illustrations seem dissimilar, but look long enough and you’ll see commonality. “I like to draw people who look crazy and are okay with looking crazy,” Joana tells me. “New York is very inspiring for that.”

Joana herself doesn’t quite fit this description. When I meet her in her Tribeca loft, the 28-year-old wears tailored overalls and a gingham shirt, more Jane Birkin than kooky, paint-splattered artist. Though, as a fourth-generation New Yorker, she knows many of the latter breed. Growing up, one family friend dyed her hair purple for decades. A babysitter wore long, “kind of terrifying” fake nails, which she memorialised in a childhood sketch. Joana’s great-grandmother, the poet Blanche Oelrichs, was something of an eccentric, as one would have called her in the 20s: “She only wore custom-made suits and ties. And she was gay.”

Joana’s work features friends as well as famous fashion oddballs, like Knight Landesman, Grace Coddington, and Zandra Rhodes, whom she’s sketched for Vogue and The New Yorker. Ultimately, she’s more interested in style than fashion. “If someone’s really beautiful it doesn’t make them a great drawing.” More captivating are people on the street who “present themselves outwardly as they’d like to be on the inside.” In other words, those of us who fashion ourselves as cartoons before anyone starts to doodle us.

One of Joana’s favourite subjects is her longtime friend Lena Dunham. The two met in preschool in Tribeca in 1989, and Joana acted in Lena’s 2009 webseries Delusional Downtown Divas. For years, Joana had trouble sketching her. “I would try to focus on her mouth, or something else, but it would never look like her,” Joana said. “But as soon as she got her little bob, I got her! Illustrations are caricatures. It never quite looks like them—it’s me through them.”

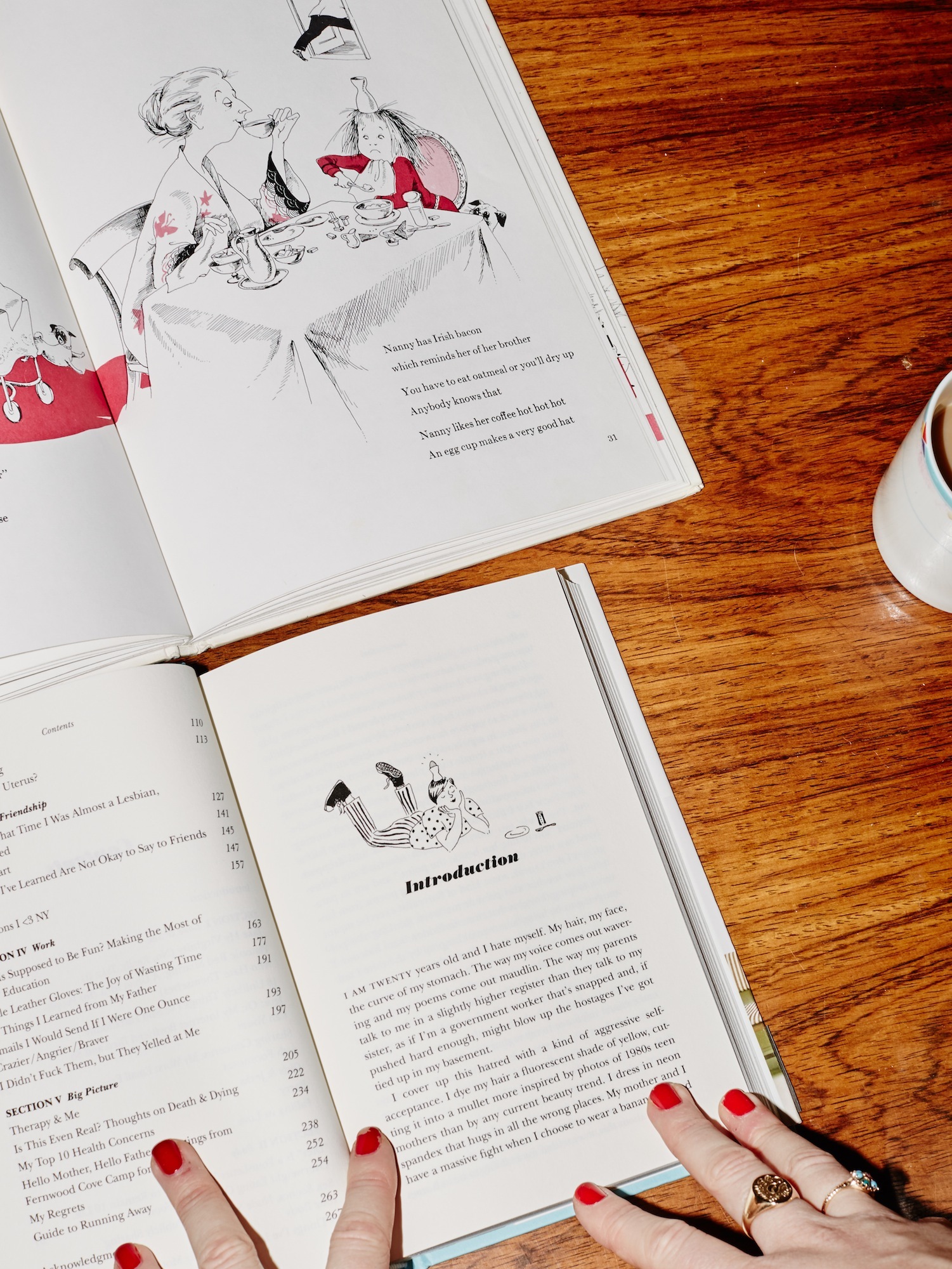

Joana’s largest project to date involves more than 70 sketches of Lena, for the filmmaker and actress’s book of essays, Not that Kind of Girl, released in October. “We have a similar sensibility. I know what things will tickle her,” Joana said. For instance, in the book’s introduction, Joana sketched Lena with an egg cup balanced on her head, an homage to Eloise, the 50s children’s book heroine who remains the Plaza Hotel’s most famous resident. “Lena’s kind of an Eloise,” Joana tells me. In 2013, in a spread for New York, Joana reimagined Eloise as a girl who lives in Brooklyn, at the Wythe Hotel instead of the Plaza. It’s practically a 6-year-old version of Girls. “I absolutely refuse to take my Adderall. Instead I leave them as tips wherever I go,” says Eloise.

To create the illustrations for Not that Kind of Girl, Lena and Joana sent text and images back and forth for months as the book was being written. “It was kind of like being pen-pals,” Joana said. Normally, her assignments are shorter: much of the work ends up in magazine features, and she also does invitations and live drawings (e.g. vigorously scribbling red carpet looks at the Met Ball). “I like that illustration is commercial,” she says. “I don’t call myself an artist. I’m not waiting around for inspiration like a mad genius.”

Joana’s mom is a capital-A Artist, the photographer and painter Gwenn Thomas. Her late father, Martim Avillez, was an illustrator. The Reade Street loft where Joana lives is practically a family archive. Paintings by her mom crown the desks covered in watercolours, paintbrushes, and paper scraps where Joana illustrates. On the other side of the room, bookshelves so high that they require a Beauty-and-the-Beast-style ladder hold thousands of comic, theory, and art books belonging to her dad. Before it was an Avillez family loft, the space was a noodle factory, and before that, a cocoa-powder factory.

Like some have done with Lena Dunham, it’s tempting to attribute Joana’s success to famous friends and artist parents. But, like Lena, such explanations wilt in the face of original, quality work. “It took me a while to realize you should go after what you like, not what you think you like,” she says. “All of my ideas come from my childhood. If it’s something that would have excited me when I was five, then I know it’s probably good.”

joanaavillez.com @joana_avillez

Credits

Text Alice Hines

Photography Kathy Lo