, , 2012

This article, by Jenna Wortham, was originally published in Aperture Magazine‘s summer issue, “Platform Africa”

Africa is often defined from the outside. Throughout history, works about the continent— films, photographs, and books—have rarely come from the people living those realities. Centuries of colonization and oppression have kept Africans from authoring their own narratives. But recent years have seen the rise of young African photographers, including Zanele Muholi, Siphiwe Sibeko, Neo Ntsoma, and Jody Brand, who challenge those notions and define reality on their own terms.

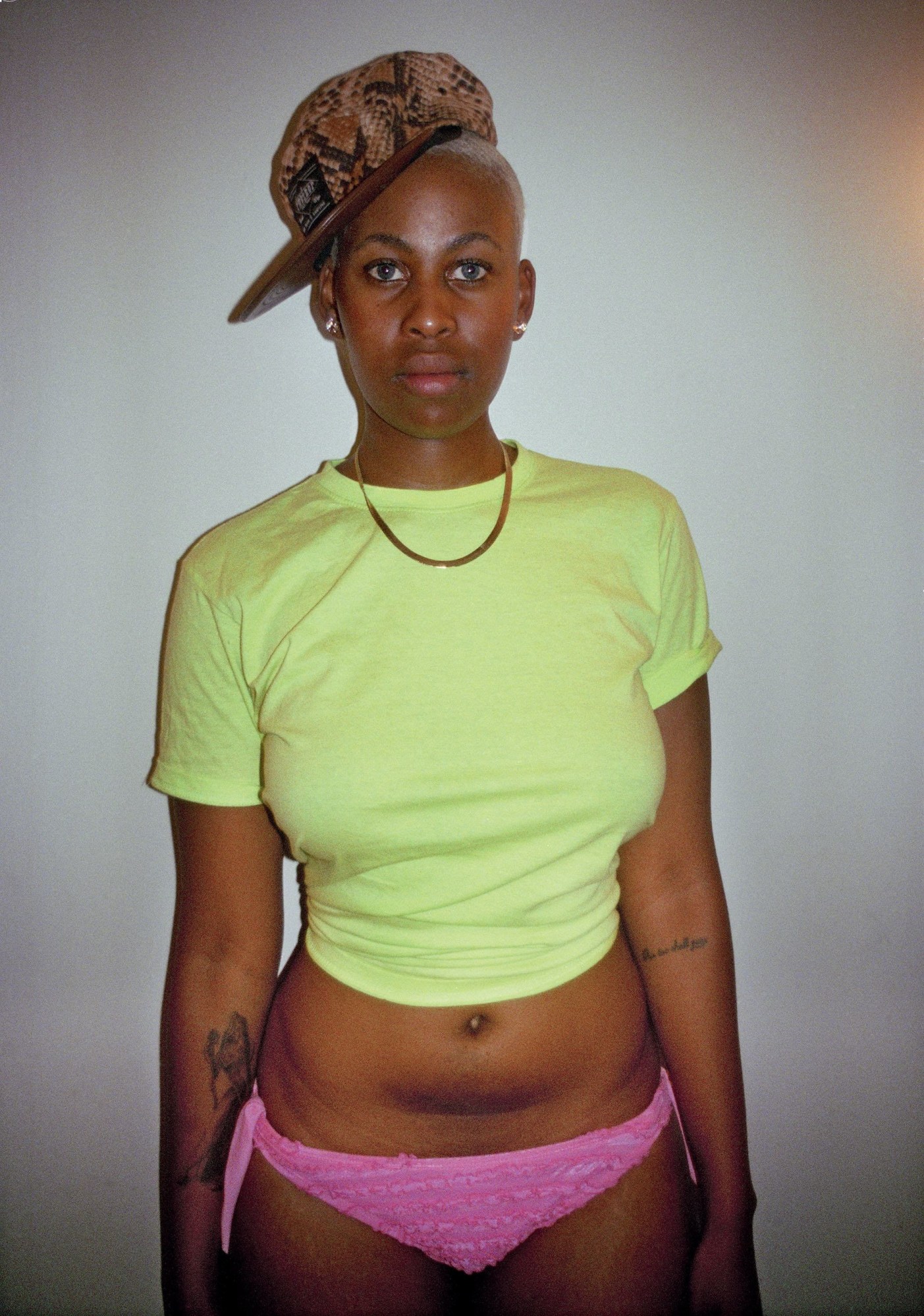

Brand brings an unmistakable Internet aesthetic to her photography. She is twenty-seven years old, so social media has defined how she interacts with the world beyond her own. For Brand, growing up in Cape Town, the Internet became a portal and a safe haven, telegraphing relief and comfort by showing how people of color live in the world. It was a place where she “realized you can be a person of color and different and alternative.” It’s why she still uses a Tumblr account to publish the majority of her work: the openness and accessibility of the platform make it available to others, like her, who crave their reflection online. The name of her page, chomma, comes from the slang for “friend”—signaling the lens that she is offering into her world, as well as the hand she is extending out to others.

Brand began taking photographs because she felt non-Africans were still owning the conversation and dialogue about African identity. “People who insert themselves within a situation and take what they want and leave—it felt very National Geographic,” she told me. It made her question what she was seeing—and ultimately, what the world was seeing. “They’re not adding anything to the conversation or the culture,” she said, “they’re just colonizing it.”

Some photographers’ work, she feels, still observes and potentially uses Africans as subjects, not protagonists. “There are a lot of power dynamics involved with photography,” she said. “Photography carries so much baggage, especially on the continent.” Brand uses a cheap plastic point-and-shoot. She doesn’t have a car, so she walks or takes public transportation. The images she makes come from personal interactions she has on a daily basis.

Brand initially planned on becoming a journalist. She enrolled at the University of Cape Town with the hopes of giving the marginalized and the underreported community a voice. But she found the experience to be traumatizing, and the educational system to be entitled and colonialistic. “I really hated everything I was being taught,” she said. She turned to photography and began pursuing a career in fine art, working for art directors and assisting on shoots.

Brand tends to photograph her friends, and there is an undeniable intimacy to the work. It is as tangible as an item of clothing. “The struggle of living in Cape Town is being belittled and dealing with covert racism, like the way the city is planned so that white people don’t deal with the reality of the majority of the people in this country because they keep them out of sight,” she said. “There are limitations to what you can do as a young person of color in this city.” Her work is about allowing black people the opportunity to look at themselves with “love and dignity.” “I take pictures of people to remind them they are beautiful and worthy and part of something and they belong to something greater.”

Occupying space—in someone’s mind, on a screen, in a gallery—is a form of protest that functions on a number of levels, internally and externally. For Brand, as a nonwhite South African, “we navigate spaces in an almost apologetic way. I want to do the complete opposite in a reckless way.” She makes images that stand in defiance of white expectations and don’t adhere to any aesthetic other than her own. They present young black and brown Africans flourishing under oppression, and influenced by popular Internet culture. Ultimately, Brand hopes to offer a lifeline to others, like her, who feel disenfranchised by the culture of their environment. “To me, that’s the power of art,” she said.

Jody Brand’s work is on view at Stevenson in Cape Town through July 15, 2017.

Read more from i-D Magazine’s showcase of work from Aperture Magazine.

Kitty de la Renza, Cape Town, 2015

Maxine Wild, Cape Town, 2015

Sam, Cape Town, 2012

Angel-Ho, Cape Town, 2014

Credits

Text Jenna Wortham

Photography Jody Brand courtesy the artist and Aperture