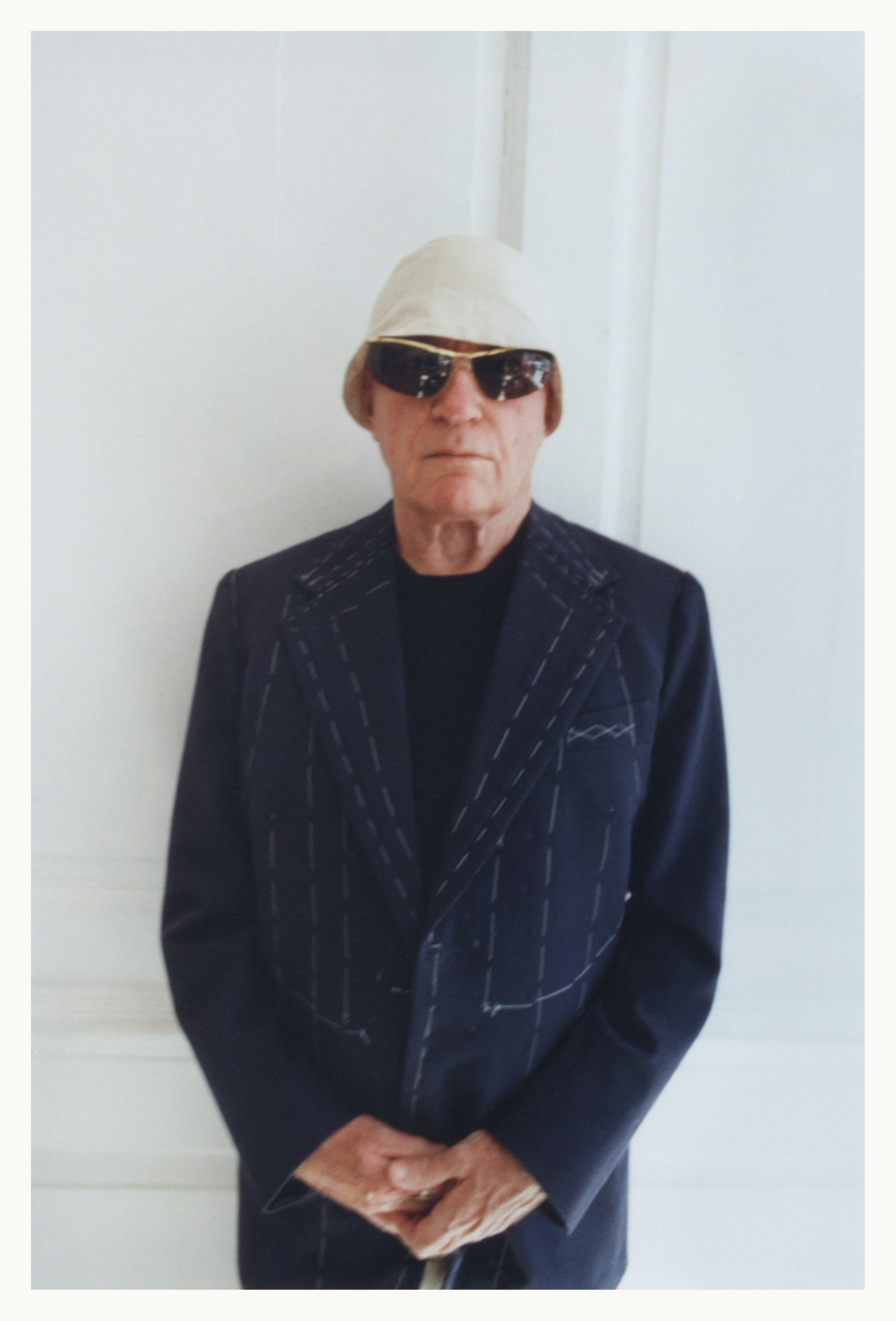

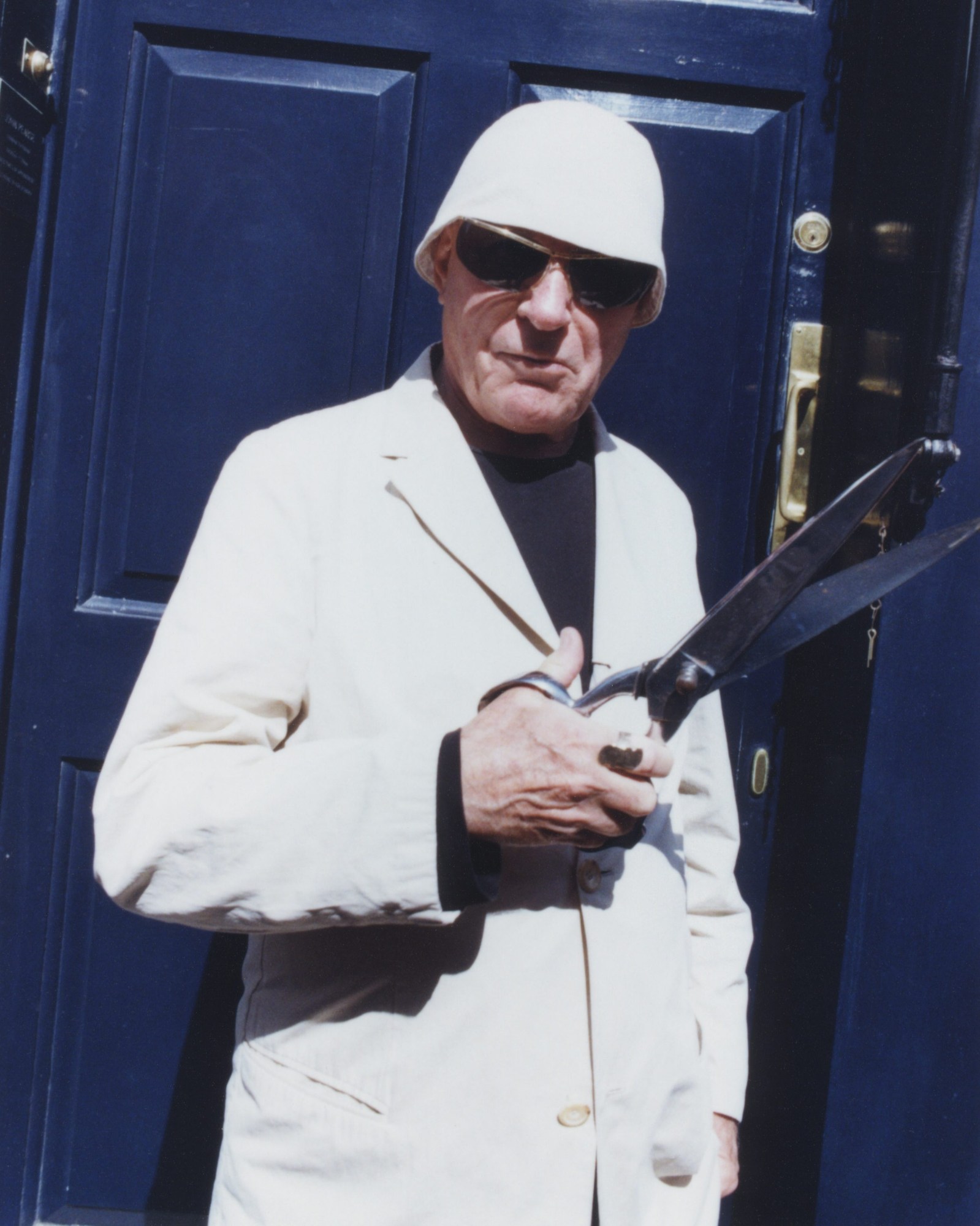

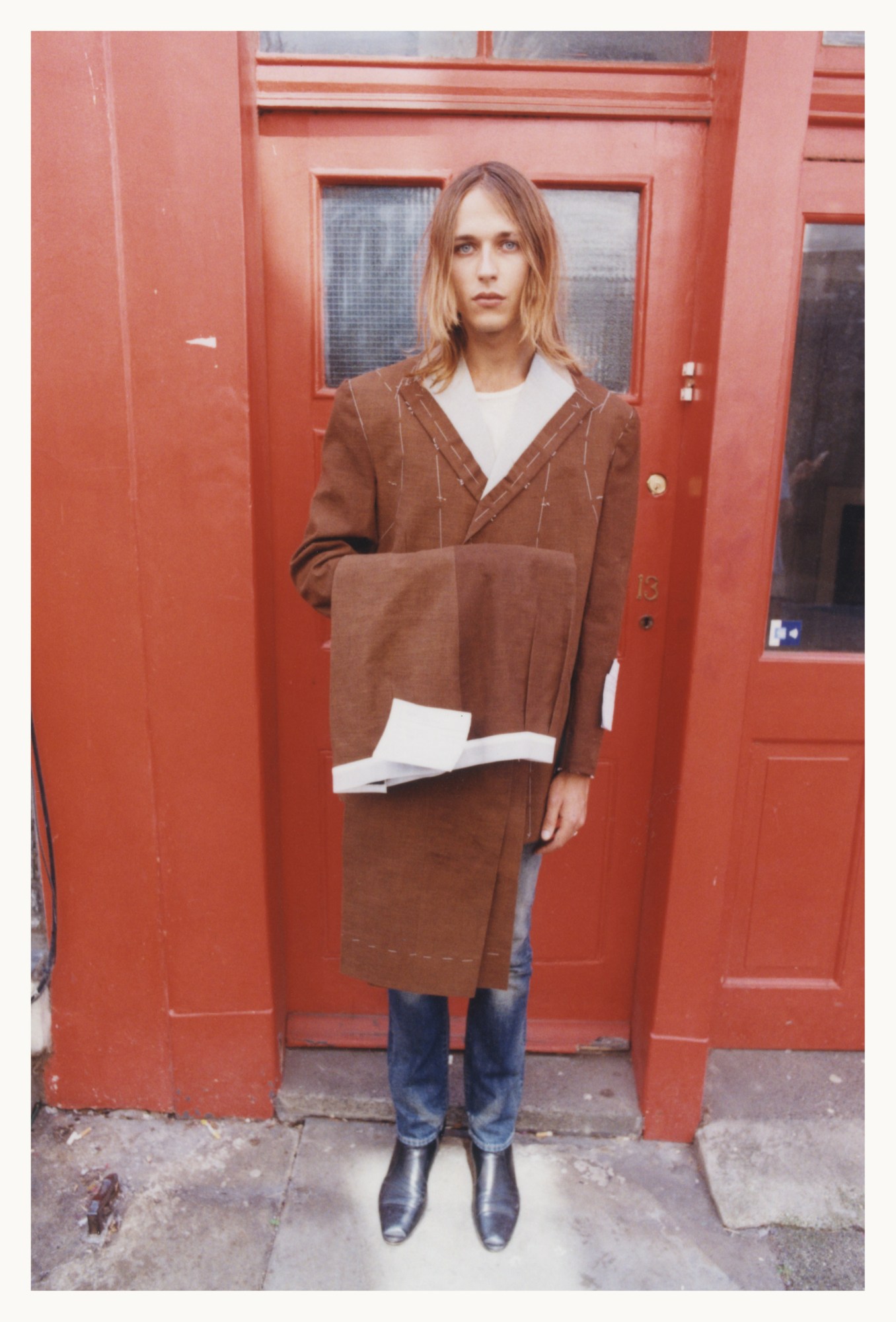

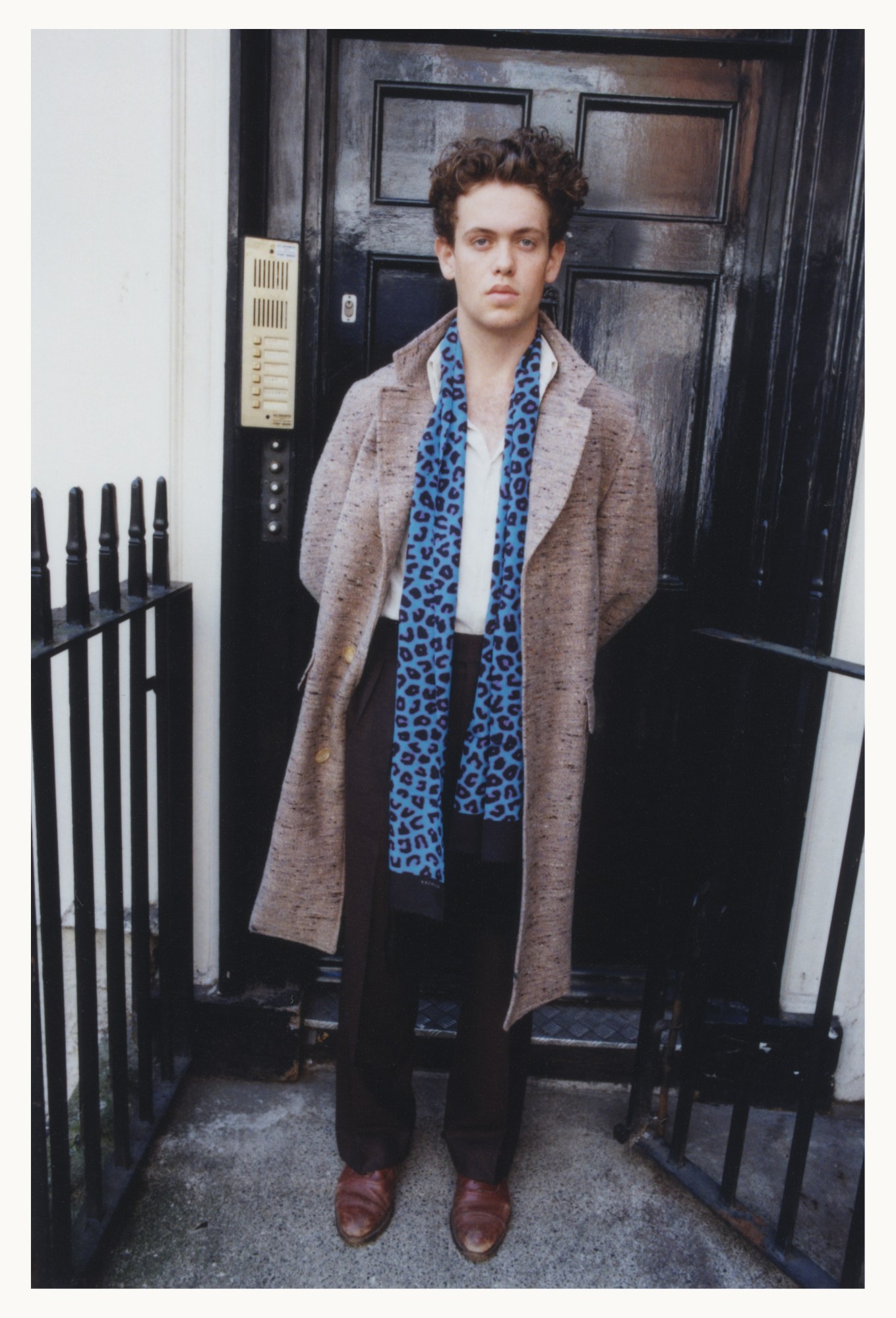

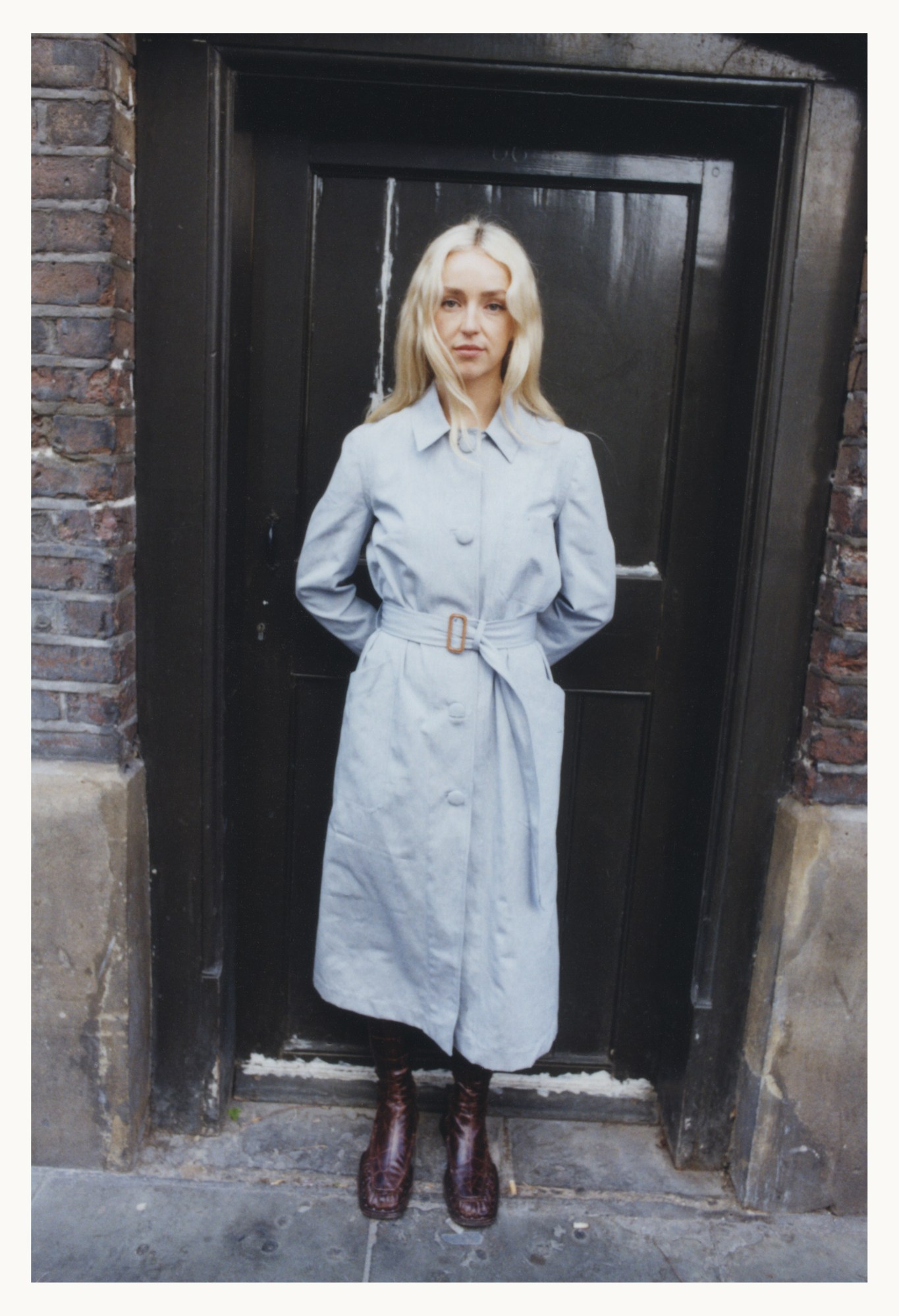

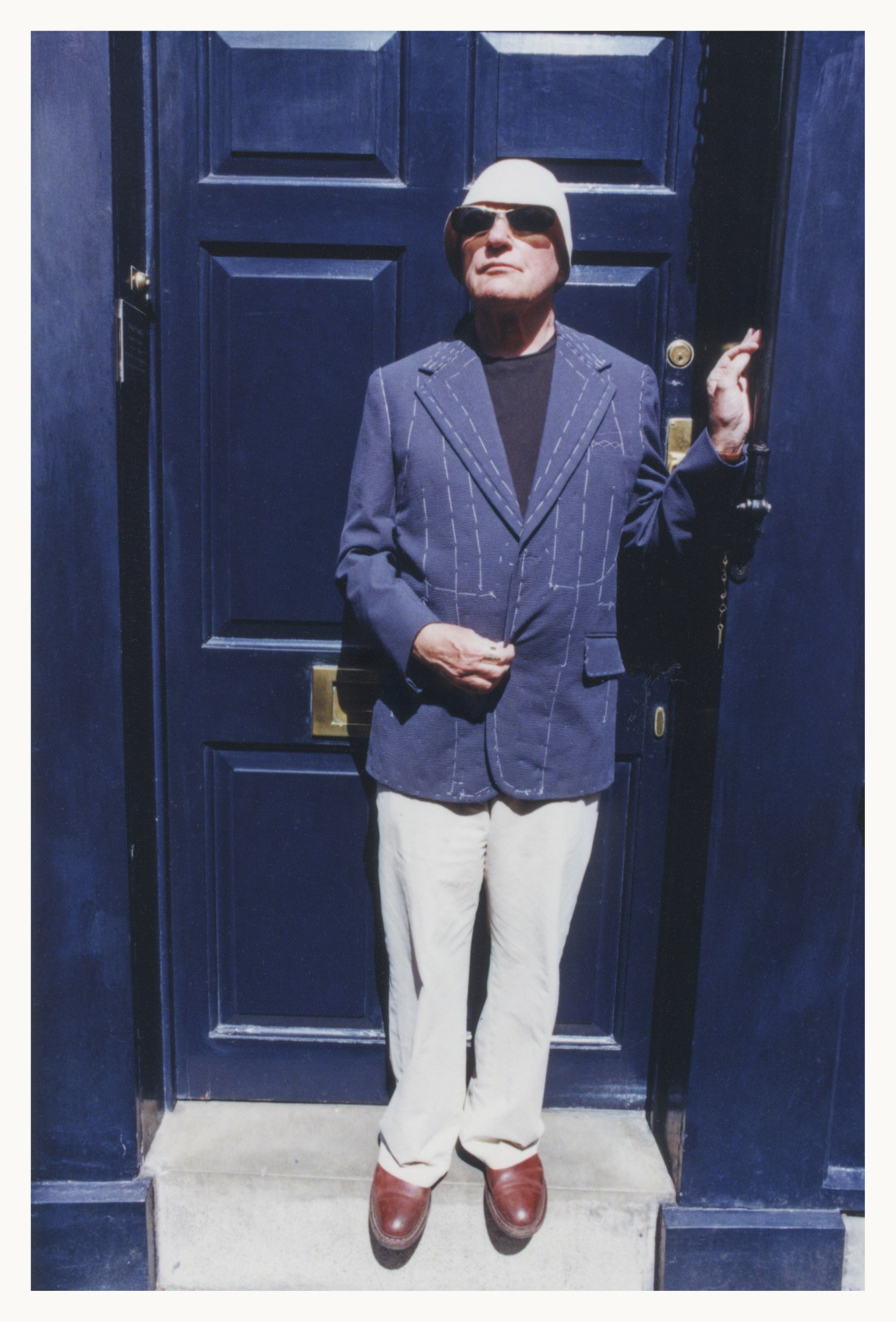

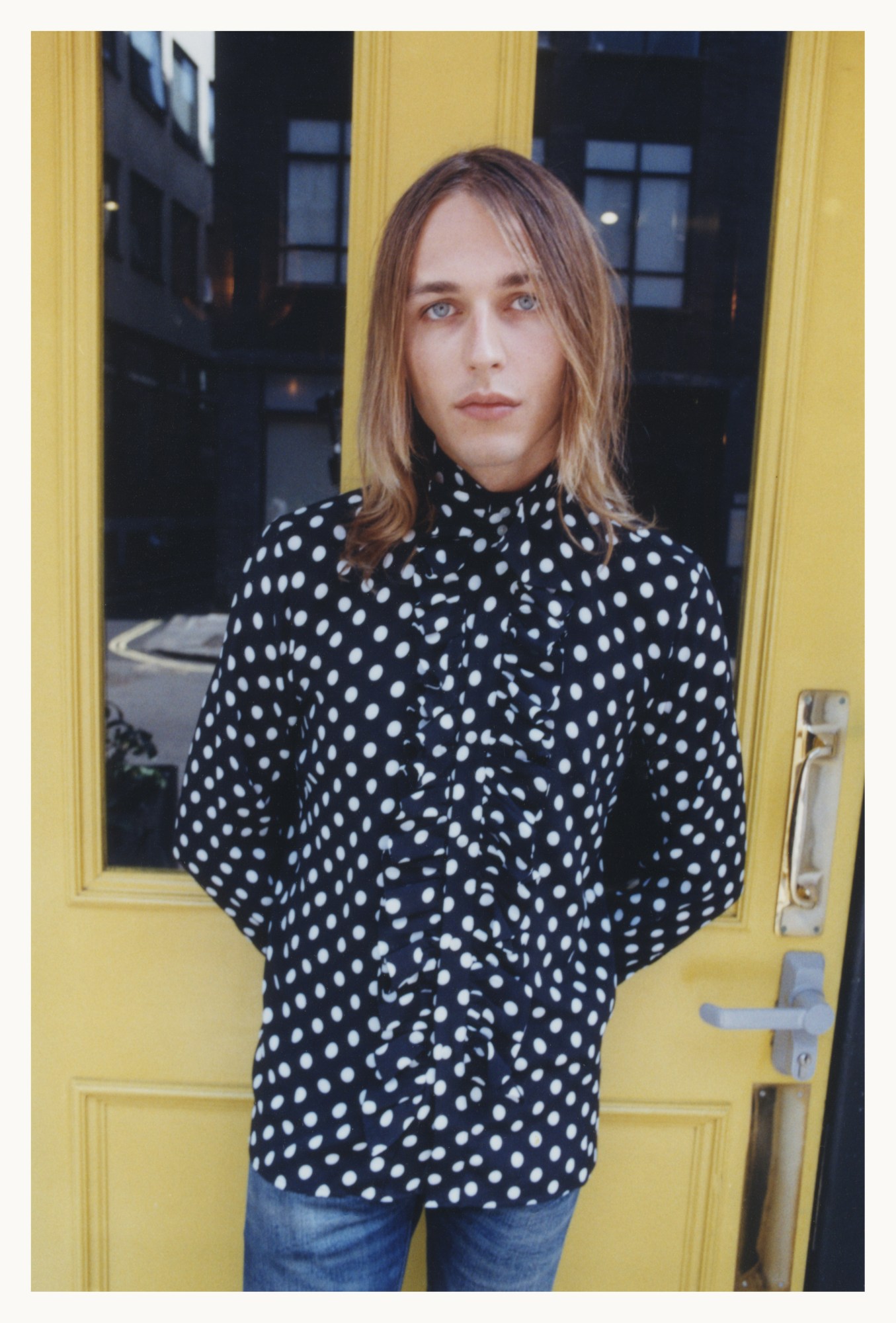

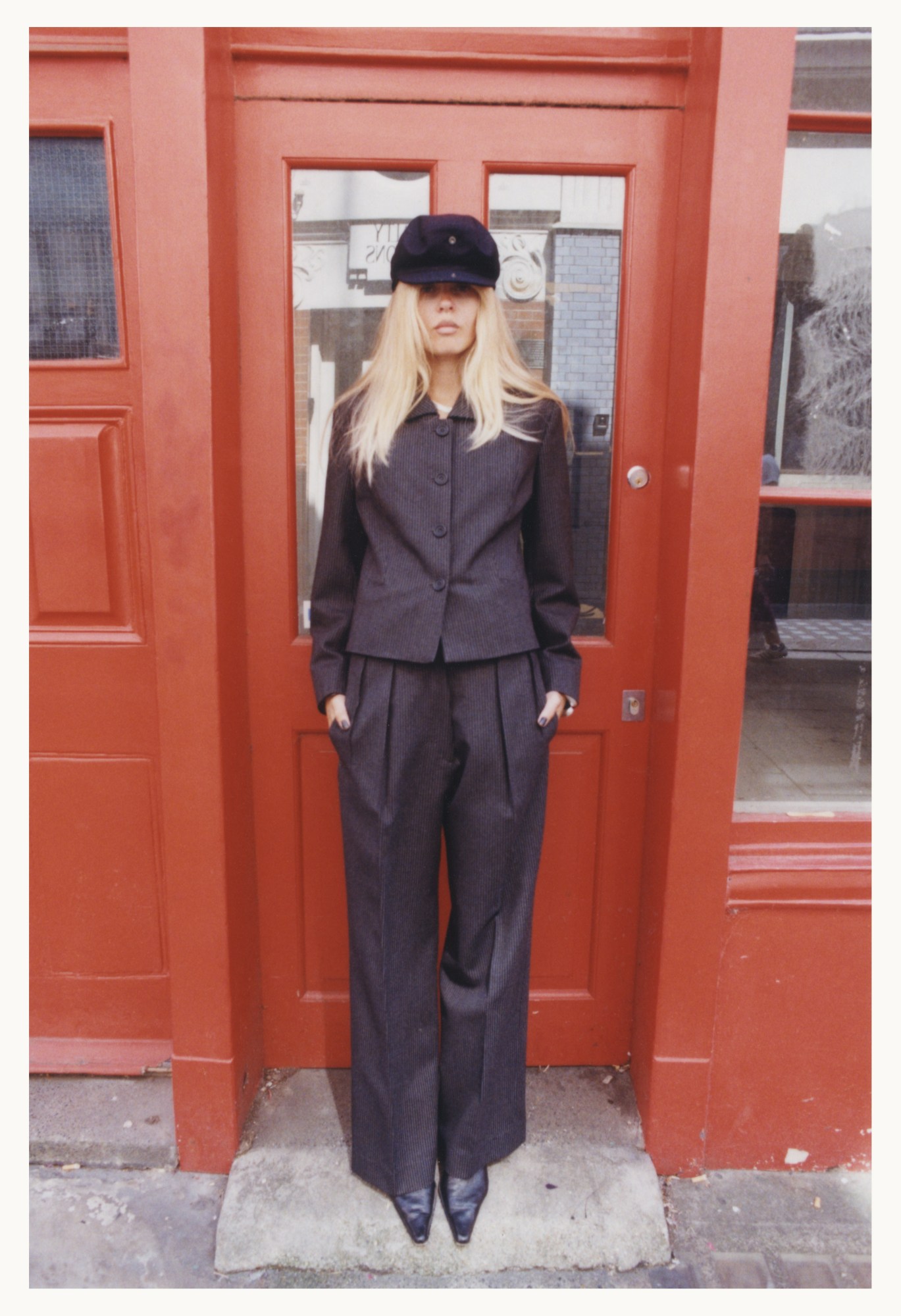

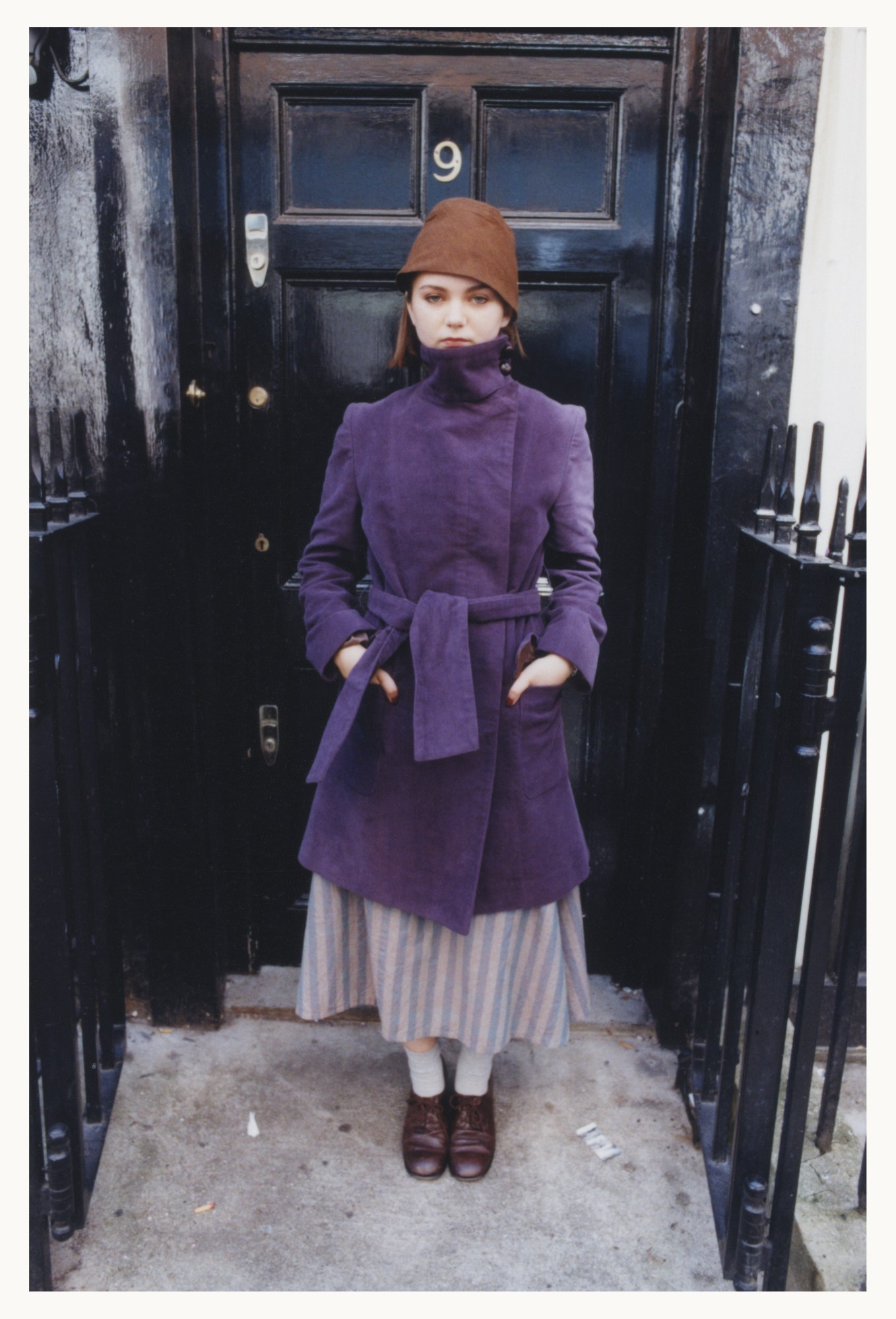

photography by LUCA WARD

I’m a sucker for tailoring and a nice suit. This, however, does not translate into me owning or wearing good tailoring or nice suits. I own one suit that I wear as often as possible—mostly because it is the most expensive thing I own and I want to get the maximum out of it—and about seven grey blazers that I’m trying to make my thing. Anyway, when I stumbled across John Pearse’s Instagram I couldn’t stop scrolling through his wonky iPhone snaps of his bespoke tailoring modelled on a coterie of young and beautiful friends, family and staff. I knew it in my bones that Pearse had lived a life and had a great story to tell, so I swung down to his store come studio in Soho to find out about his incredibly eclectic life.

Jackson Bowley: For those who don’t know you, how would you describe what you do?

John Pearse: I’m a tailor by trade, but by token of having the shop, I almost feel like a curator of clothes. We make things to sell, we restore things, and there’s always something being produced. There’s usually a story behind each piece—a memory in the fabric somewhere. I’m also a bit of a psychoanalyst. When someone comes in and says, “I want a suit,” I have to read them—where they’ll wear it, who they’ll be in it.

How did you first get into tailoring?

I left school at fifteen. I knew I wanted to be in Soho, even if I didn’t know exactly what I’d do. My first job was in a print factory above the Marquee Club on Wardour Street—I was training as a lithographic artist, but I couldn’t stand the noise of the clanking of the machinery. I thought, I need a quiet job, and I want a suit. The only way I’d ever get one was to learn to make it. So, I walked over to Savile Row and ended up at Henry Poole. They didn’t have a job for me, but they sent me to Hawes & Curtis on Dover Street. Suddenly I was an apprentice coat maker. We were all young, sitting cross-legged on the floor, gambling away our three guineas a week and selling scrap cloth on Brewer Street for extra cash. It was like Fagin’s Lair for tailors.

Did you have mentors?

There were a few older tailors who’d take the time to show you something—how to set a sleeve or shape a collar—but your bosses didn’t want you learning too quickly. You were cheap labour. I realised I didn’t want to be someone’s apprentice forever, so after a couple of years I left to travel.

Where did you go?

Spain first, then Morocco—like every young person running from London at the time. When I came back to London, one of the girls that was staying with us in Spain invited me to a basement flat on Gloucester Place where I met a young couple surrounded by old clothes. They were starting a shop on the King’s Road called Granny Takes a Trip and asked if I’d be part of it after realising I was a tailor.

The King’s Road in the ’60s, what was that scene like?

It was literally the end of London—we were based at the World’s End, across from the pub. Tailors I knew told me, “You haven’t got a hope in hell down there.” But it became the centre of everything: music, rebellion, fashion. The Stones, the Beatles, Hendrix—they all came through the door. Brigitte Bardot, too. Veruschka wore one of our dresses on the Blow-Up poster.

The shopfront changed constantly, at one point I cut my old 1947 Dodge that had broken down in half and had it bursting through the window. That was my way of saying I was ready to move on. I was in a band at the time. I played a one-string instrument called a phono fiddle. I would plug into an amplifier which would give it this drone that sounded like psychosis. We went to Amsterdam to play on a TV show but that fell through. We ended up playing at Fant Club but the various egos of the band ended up imploding and we split there. I came back to London via Paris during the ’68 riots.

And then you also ended up in Rome?

Rome was another world. My girlfriend at the time was Donyale Luna, the first Black model to appear on the cover of Vogue. Federico Fellini was filming Satyricon, and she was in it, playing a 2,000-year-old witch doctor. On Saturdays, we’d have supper at Fellini’s place.

One night, we went swimming at midnight. Donyale wouldn’t come back in from the sea, so Fellini turns to me and says, “Brother John, can you get her?” I shouted, “If you don’t come back in, we’re just gonna fuck off and leave you here!” and she finally came in. Fellini laughed and said, “Brother John, you could be a great film director.” I came back to London and made a feature called Moviemakers—sort of a farewell to that whole scene. It was like a requiem for the King’s Road. It went into the London Film Festival but it was poorly received by the critics. I also made a short film, Jailbird. I even had a project with Patti Smith in New York—she’d perform in the old Women’s House of Detention—but it fell through. Raising money for films back then was incredibly difficult, today you could make a movie with your phone.

What brought you back to tailoring?

I was at a party when a guy said, “You made me a suit in ’67, would you make me another?” That led to a few more commissions where I was tailoring from my home. I moved here in 1986 in the basement, the main storefront used to be a bookshop. It was like The Man from U.N.C.L.E.—the most exclusive tailor in the West End, but you had to know where to find me. Now I’m making clothes for the offspring of my old clients.

Who would you say the best dressed movies are?

I would say, the Italian movies with Marcello Mastroianni and men in black suits looking sharp. That was certainly it. Also overcoat movies, gangster movies, over chalk striped suits. The double bill Jimmy Cagney movies, you know. Also Humphrey Bogart, wonderfully dressed characters.

What city do you draw the most inspiration from?

I live three months of the year in Uruguay and I have a pop-up shop there sometimes. But I think Italy has always been interesting. They’re well dressed. The French are a bit more peacock and only wear black jackets, you know, there’s a uniform. So I would say the Italians. They have some very good tailors in Naples.

What would you say makes a great suit?

Comfort. That’s the best feeling you can have. Often if the suit is well made and doesn’t even fit you that well It still can work. The other thing is, some people can wear clothes and the clothes don’t wear them. It’s an attitude. You carry it.

What’s it like during a fitting?

It can be quite daunting. Obviously you want the customer to be happy and you’ve only really met them for around three fittings. On the final day it’s like opening a play, the curtain goes up and they’re standing in front of the mirror, looking at themselves. Do they like it? Do I like it? Often there’s a gestation period, when they walk out in the suit and I’ll see them in a year’s time and I think, who made that suit, it looks really good? Did I make that? Because that’s the other thing, things leave the studio and they’re gone from your life.

If not tailoring, then what would you want to do?

No, I think I’m happy. It’s been a good life and it’s social this place. I’m always meeting different people. It could’ve been film if I’d have gotten more breaks.