When Boyz n the Hood was released on October 1991, it hit screens at a particularly interesting — and incendiary — time in contemporary American culture. Public Enemy and N.W.A. were fighting the power — and fucking the police — loudly, angrily. It was two years after Reagan’s crack-cocaine reigning two terms, halfway through George Bush Senior’s term, during which time he ushered in the first Gulf War against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Mike Tyson was arrested for rape, Jeffrey Dahmer for the murder of 11 men and boys. Amateur footage of the savage beating of a young, black man called Rodney King by members of the LAPD was leaked. The 1992 riots were a mere eight months around the corner. Parts of America were, almost literally, on fire.

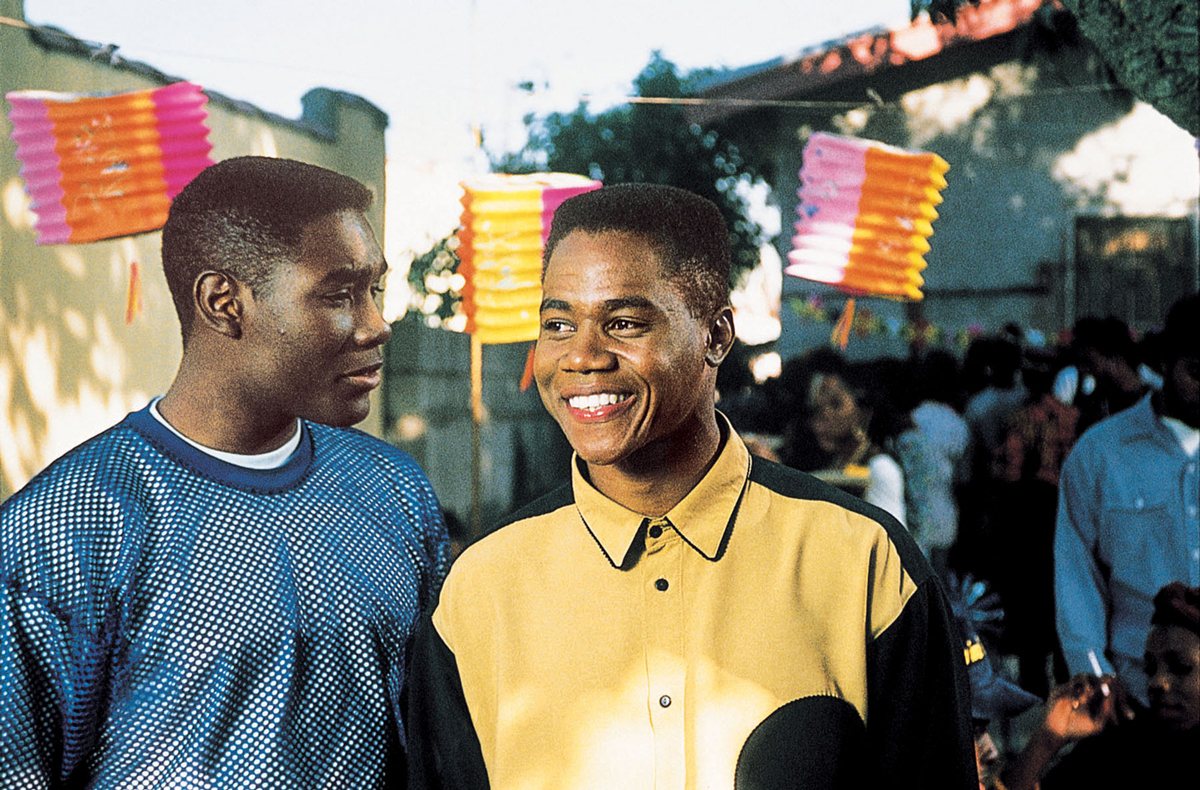

Following Ice T’s debut in Mario Peeble’s New Jack City, a then 23-year-old John Singleton — a novice filmmaker still in film school — decided to write a film focused on his own upbringing in South Central L.A. Rather than recreating Peeble’s otherworldly gangsters, Singleton’s semi-autobiographical Boyz n the Hood was a much more nuanced take on the influx of crack-cocaine that decimated communities during the 80s and 90s. The film opens with a sense of nostalgia and naivety, but its lead characters are soon forced to abandon any notions of childhood as their lives became seeped in a litany of gang violence and police brutality. This story wasn’t uncommon to the characters of Ricky, Doughboy, and Tre. Boyz opens with the statistic that (at that time, in 1991) one out of 21 black males would be murdered before he is 25 — most at the hands of other black men.

The film was an intense and unflinching look at both black-on-black crime and the factors that contribute to its prevalence. It earned Singleton an Oscar nomination, and made a movie star out of Ice Cube. Boyz was soon flowed by a slew of other movies that examined the working class African-American experience, including Ernest R. Dickerson’s excellent Juice, starring Tupac.

As the film celebrates 25 years with screenings throughout the UK this week, i-D meets director John Singleton to reflect on his powerful coming-of-age drama.

How is life? What are you currently working on?

I’m doing good. It’s a warm sunny day in Los Angeles. I just finished up a season of Snowfall; it’s about Los Angeles in the early 80s, before the crack academic.

How different is it to create for TV, compared to film?

It’s the same really; you just work faster. It’s great now because television has become more cinematic. Years ago, I would have been more averse to television but now more people have flatscreen TV, which are more like cinema screens, so you can compose for the TV screen the way you would with film.

What are your memories of making Boyz n the Hood as a young, inexperienced filmmaker fresh out of film school?

It was great, it was a moment where I was learning everything. I mean, I’m still a person that learns, but I knew nothing when I made Boyz n the Hood. I was at the front of it; it was a whole new experience for me, as a person. I was finding myself as a person and as a filmmaker. You know? I mean, I had help from my crew, but I had to watch films and learn from that.

What did you want to say with Boyz and do you think you achieved that?

Oh, I said a lot. I really wanted to establish a narrative of what was going on in my neighborhood.

How has South Central changed?

It’s changed, there’s still things that happen but it’s a lot less violent.

One thing that hasn’t changed is the relationship between the police and young African-American men.

Yeah, that’s never changed. That was going on before the movie and it continues today.

Is it worse now? The perception certainly seems to be that things are no better.

I think it’s better now than it was in 1991, the relationship with the police, but the neighborhood has changed a lot. People have moved away, there has been gentrification, different elements have moved in and changed it.

How do you reflect on the expressions of black popular culture in 2016? Back in 91, Boyz was coming off the back of NWA, Reagan, Rodney King, and Public Enemy. Today we have protest and protest songs, but it’s a different narrative, a different climate. How do you find pop culture’s responses to what’s happening now, compared to when you were making Boyz?

It’s the same but it’s expressed in different tones. The passion is still there but in more muted tones. The passion is still there; you listen to some of Kendrick’s music or Beyoncé’s music, there’s still protest in there. Back in the day, we were a little less sophisticated. People are a little more refined in the way I protest, I guess.

But has the sense of urgency gone — can the protest be as powerful as it was in the late 80s, early 90s?

They don’t make films like that anymore, honestly. [Boyz] came out at a time where studios knew they didn’t know how to talk to those audiences. Now, they feel like they can micromanage and get that audience. Most of the black films that come out now, they’re really micromanaged by studio handlers and they don’t have that pure vision — unless they’re totally independent.

What do you have to say, as a filmmaker, in film and TV today?

I have a lot to say. With this new show [Snowfall], I’m reflective of the past, but I’m also knowledgeable of what’s going on in the contemporary America, black America and white America, and I want to reflect that in my continuing work. I’m also getting older and looking at the past in certain contexts.

In 2014, you said Hollywood wasn’t letting black Americans make black films. How do you feel in 2016 — given the range of black film, from Tangerine to Moonlight to Ava DuVerney’s The 13th?

There are very few films that are coming out that I’ve seen that have the passion and the verve of films of the past. One of the best films that came out this year was basically destroyed by the personal life of the filmmaker [Birth of a Nation] — that superseded the film. I don’t know if you’ve seen it yet but it’s a very powerful film and the audience didn’t find it because of the guy’s past coming back to haunt him. I think there was forces at work that didn’t want that film to work and didn’t want to have the Black Lives Matter generation get behind that film. They got kind of scared thinking that something would happen if the people who were in the streets rioting in protest, got behind it. It was an unwarranted fear.

You worked with two of pop culture’s biggest icons — Tupac and Michael Jackson [Singleton directed MJ’s “Remember The Time”]. Do you reflect what voice they may have had in these times?

It was a big part of my life and it’s hard to bring it up, it’s very painful. Pac was the quintessential actor for me that I could have made all of these pictures with, and he was taken away.

Do you think there needs to be a Boyz N The Hood 2017?

Yeah, I mean, the themes are still there. I look at that picture as a teenage film; it’s a coming-of-age. There’s always going to be people coming of age.

What would you like to do next?

I’d like to do a film about post-Obama America. What happens after Barack Obama is out of office? When Obama came into office eight years ago, the country was very polarized; economically we were in flux because so many forces were at work controlling our economy and for selfish reasons. Obama came in as president as a healer; he basically saved the economy, protected the nation. But there’s been a contingent against him as a black president of the country, psychologically. And he’s kept a positive point of view throughout it all, which takes a lot of strength. But what happens after that, you know? What is this country going to be? We will find out in the next few months, and that’s interesting, no matter who wins the election, what’s the country going to be? I’m interested in a contemporary film set in post-Obama America. I think it’s going to be more intense.

What do you think Obama’s legacy will be?

I have no idea; I have no idea what the future is going to be. It was positive, he was a healing factor for the country — so what happens when the healing factor leaves?

Are we in danger of Trump being the next president?

He has no chance.

From a black president to a female president, then. What does this say about US politics today, and how do you think Hilary will fare?

I think she’ll make a great president, but she faces the same situation as Obama; because Obama was a figurehead, he had to endure so much extra within government. Psychologically, what his very presence did to certain older generational people, it bought out their racist tendencies, and he had to go through that and the country had to go through that that. I think with Hilary as a figurehead, even though she will make a good president, she’ll have to go through the ego-massaging factor, as if a woman can’t do what a man can do — there will be a lot of that over the four years. There will be an interesting time with sexual politics. You have a patriarchal society that automatically changes because a female president comes to power. How are some people going to take that?

What do you think is the legacy of the Boyz n the Hood?

The film is still very, very powerful; the legacy is really showing that moment in time of the neighborhood I grew up in, South Central Los Angeles, and how beautiful people are, and what they were going through at that time. I think it’s a timeless movie — a classic coming-of-age movie. I accomplished what I wanted to, in creating something people wanted to see more than one time.

Why is filmmaking important, both as entertainment and culturally or politically?

Because films are a reflection of life. Over the years, people of various cultures, their voices were excluded from film and media. It was pretty much a white-dominated medium, so how is it when you don’t see yourself onscreen? You feel invisible, you don’t feel validated. The reason we have film and TV is the same reason cavemen drew on walls — to show who I am, I’m significant, I have a soul, I existed at a certain time. It’s the same reason people make film — they want to get their stories onscreen, they want to validate their own existence.

John Singleton’s ‘Boyz n the Hood’ is showing next weekend as part of the BFI’s Set It Off season. Get tickets here.

Credits

Text Hattie Collins