Dan Martensen’s story originally appeared in i-D’s The Icons and Idols Issue, no. 359, Spring 2020. Order your copy here.

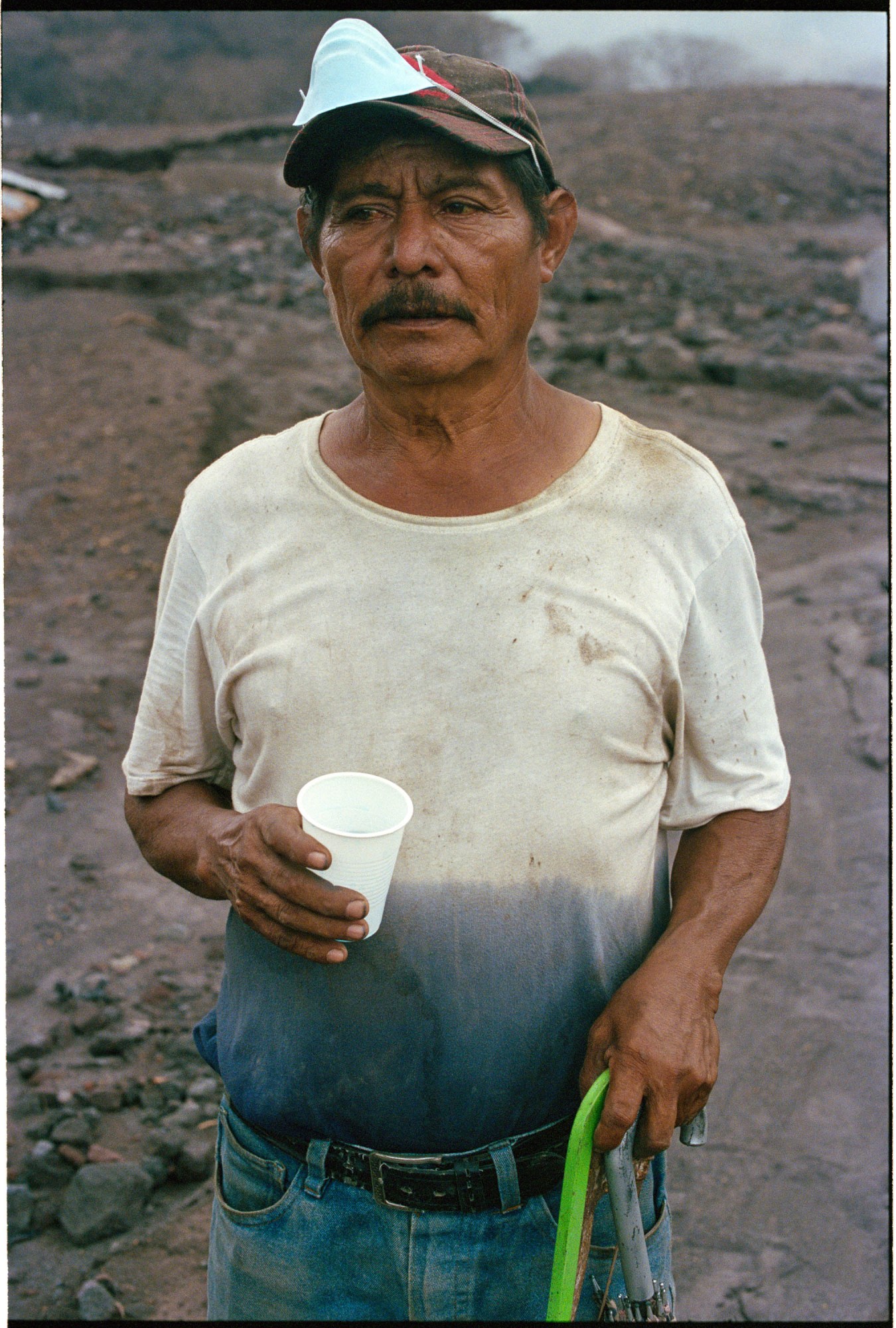

In 2018, I was sitting in a pick-up truck in a remote part of Guatemala, headed up the backside of the recently erupted Volcán de Fuego (“Volcano of Fire”). The truck was loaded with over 500 pounds of hot food, driving on a road that could be described, at best, as treacherous — and that was before it had been washed out by burning hot mudslides. I was with my new friends, delivering food to local people who had been cut off from civilisation by the erupting volcano. We were racing against the clock. If the rain came before we arrived, we would risk being stranded on the active volcano as well. I realised I had found what I was looking for… then I got bitten by a stray dog.

Two weeks before this, I had visited Puerto Rico on assignment to photograph José Andrés and the efforts of his organisation, the World Central Kitchen (WCK). I had followed José’s work for some time and was keen to contribute to the cause he represented. José founded the WCK in 2010, preparing meals for people in Haiti in the aftermath of its devastating earthquake. Since then, the organisation has provided food in the wake of natural disasters in Cuba, Uganda, Cambodia, The Bahamas and more. To me, José was a culinary god. But he’s also humble and passionate and maybe the most charming man I’ve ever met.

Following the devastation of Hurricane Maria, José jumped on the first available plane to Puerto Rico alongside Nate Mook, his director of operations (now CEO). Despite significant obstacles — pushback by FEMA, power cuts, barely any drinking water — José built a kitchen and started cooking. On their first day, the WCK provided 1,000 meals. On the second, 2,000. Each day, the machine would run more smoothly, and at the height of their operation there, the WCK were serving over 180,000 meals per day from 18 different kitchens and a fleet of trucks.

Making this food not only fed the island, but it got local businesses — farms, bakeries, grocers — up and running again. People were going back to work; the food nourished them and gave them purpose. José saw that most organisations’ efforts often overlook that in the aftermath of natural disaster, economic recovery is impeded by the large influx of products donated to the local organisations, which effectively stymie local businesses. By simply ordering bread from a local bakery to feed the people, the WCK put the local baker back to work. The WCK does more than just give people food — it offers them dignity.

I like to think my experience working with the WCK gave me the confidence to do great things, even if they are small — even if they just look like a few plates of hot food. In the months since going to Puerto Rico and meeting the men and women who volunteer with the WCK, the focus of my work has changed dramatically. I began travelling with the organisation and documenting their efforts, recording every mission; from the wildfires in Australia and Northern California to their efforts at the Mexican-American border, in Indonesia, North Carolina and Guatemala. As José says: “Life starts at the end of your comfort zone.”

These photographs were taken on our travels around the world with WCK. This is only some of what I have seen so far. Back in London, about two months since I last saw José, we hopped on a phone call to discuss the work he’s done and what we experienced together…

José: Man, we’ve been in so many places together. Dan: I know, it’s funny when you look back at it all. My god. It’s funny to have good memories from these places, you know what I mean? But it’s such a positive experience when I look back at where we’ve been, and that’s a testament to you and the World Central Kitchen. I guess the first question I have for you is, when you look back on Puerto Rico today, what do you think about? When I think of Puerto Rico, I also think of the first project we did in Haiti, 10 years earlier. We got to Haiti with four people, and my friend Nate, who was there to document what we were doing. In Haiti I was still learning, but in Puerto Rico I was mature. I’d also been in Houston in 2017, after the hurricane, which was an incredibly important moment for me, personally, because it was the moment I realised how much I could actually help. We were in the convention centre, feeding the thousands of people who were using it as a shelter, and I realised how badly prepared the powers that be are in planning for these things, but how adaptable the WCK can be, with our small team, and make a big impact. You can, through food, connect with communities, really understand what they need help with. I thought Houston was badly organised, but when I got to Puerto Rico, well… the Red Cross were claiming to be there, the Salvation Army, too. But what they were doing was barely scratching the surface. I realised no one was responsible, there was no plan at all. We planned to be there for just a week, but we kept going; we didn’t have the money, but we wanted to help. We wanted to feed everyone, which is impossible, but in life you have to dream big, right?

And you’re also helping the local community by getting them back to work, helping in the kitchen. You can do so much by being really flexible. Exactly, and at a fraction of the price. I remember, in Puerto Rico, I called my wife, and I just said: “I’m not coming back anytime soon.” There was so much to do.

I want to ask about Guatemala quickly. Because in Guatemala, we were in a place where, even if there hadn’t been a natural disaster, well these communities were hurting anyway. The people in these communities live really difficult lives. The situation isn’t good anyway; these people are already hungry.

I think in the future the WCK will hopefully be able to play a bigger role. I want to help these communities beyond the immediate emergency. For example, what we are doing in Puerto Rico right now is that we’re trying to lift people up. We want to help businesses that are employing people, that are creating sustainable economies around farming by creating jobs and feeding their fellow citizens in the process. It will take us a year or two to see how well we’ve done, because the success will have to be sustainable, durable and real.

When you leave, you want to leave it a better place than it was before the hurricane.

Exactly. We want to create some permanent change. In the Bahamas, for example, we’ve been subsidising new kitchens for homes that need them, trying to create some kind of normalcy in people’s lives. We want to give grants to set up sustainable, useful, local businesses, help local people to open fruit stores or vegetable stores, for example, because banks and private businesses aren’t supporting them.

When Wilmington, North Carolina, flooded, this was the first time you were somewhere in advance of the problem, right? It was still a crazy situation, but you were as prepared as you could be?

Well yes and no. We were already in Haiti when the hurricane came, but that’s because we were already there helping out because of the earthquake. That was a massive learning experience, because we saw how everything works with the NGOs, how the mechanisms operate. And often the NGOs move everyone out in advance, because they don’t want to leave a load of people to face down a hurricane. So we learnt a lot in Haiti, but in Wilmington we really worked out how to be properly prepared, how to make good decisions in stressful moments.

How is it going with fundraising for the organisation?

If I actually stopped and thought about money, we wouldn’t be anywhere, we wouldn’t be doing anything. We have problems with money. It’s not easy. But I don’t let that stop me from going to Puerto Rico, from going to Haiti, from trying to make a difference. We will help if someone is in need. And hopefully it’s working – it seems to work at least. We have someone in the Philippines now, we have some people in Albania now, and everywhere we help makes us better the next time we need to help somewhere else.

I’ve seen you guys evolve so much since you started. It’s incredible, it’s insane.

The basics are the same everywhere – you just need to be able to adapt, and you can get better at adapting when you have more experience. A few years ago we had two people on the payroll and now we have 30, so that obviously helps, and we have at least some money now, too. We have an amphibious vehicle, which helps a lot. I remember the first time we got to use a helicopter to deliver food in Mozambique: it was incredible, because suddenly we could access all these places that we couldn’t before. I hate losing food, or not being able to help a community because it’s too difficult to get to them, because the rivers are flooded, the bridges are broken, the roads are destroyed. In Mozambique, we couldn’t get to these people, and then suddenly we managed to get a helicopter. You can be incredibly resourceful when you’re under stress, when you’re trying to work out a way to help people. They say that life really starts at the end of your comfort zone. When you take people out of their comfort zones, that’s sometimes when what’s best about us shows up. When you do the things you didn’t think were possible within you, you not only surprise yourself, but you surprise those around you.

One thing I wanted to get into: we’re doing this story for i-D. It’s a fashion magazine but it has always been committed to covering these kinds of issues, and has a young readership too… I think there’s a point in all of our lives hopefully, if you’re lucky enough, that you feel a call to service, you feel like you need to do something. And I wonder what you would want to tell this generation, who are set to suffer so many crises around the world. There’s going to be people reading this, who hopefully will be inspired by what you’ve done. Sometimes it seems very difficult to make an actual difference, so what would you say to them?

I would say: be optimistic. And I would say it’s okay to carry a pin. It’s okay to wear a shirt with a message. All of these things are okay. But this is the marketing side of things – we need boots on the ground, we need action, too. Some big problems have very simple solutions, and sometimes we can make a difference personally. You know, go out and plant some trees, and that will make a difference. If you feel like the institutions that are meant to serve us don’t, then campaign to change them. I think there’s no substitute for action. If you want to see less hunger in the world, feed people. If you want to reduce CO2 in the atmosphere then, yeah, plant those trees. Use less plastic if you want there to be less plastic in the world. Doing something can inspire other people to make a difference, too. And if we come together, we can create a movement that they won’t be able to stop.

Credits

Photography Dan Martensen

Text Dan Martensen