Raised in Paris by a French-Basque father and a Chinese-American mother, designer Joseph Altuzarra worked with houses on both sides of the pond (Proenza Schouler, Marc Jacobs, Rochas, and Givenchy) before launching his own New York-based label in 2008. This multicultural upbringing profoundly shapes Altuzarra’s work. On his runways, we find a balance between French feminine sophistication and easy American glamor.

Unsurprisingly, Altuzarra has drawn design influence from a vast array of French and American films. Among them: Luis Buñuel’s Belle de Jour (an erotic dramedy released in 1967), Just Jaeckin’s Emmanuelle (mid-70s softcore porn), and Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands (a wholesome, classic Christmas story). Yet his favorite movie — and his selection for i-D’s Fashion and Film series — is neither French nor American. It is very, very British.

Altuzarra chose to screen Sally Potter’s Orlando because, “It’s a film that’s really had an impact on me aesthetically and personally,” he tells i-D. The arthouse darling, released in 1992, “was probably one of the first times I watched a film that was so related to gender, and that was very impactful for me.”

The film loosely adapts Virginia Woolf’s Orlando: A Biography. Published in 1928, the novel is a satirical history of 400 years of British literature, and today regarded as one of Woolf’s best. The story follows a young poet born into Elizabethan nobility, who is mysteriously granted immortality. Over the centuries, Orlando traverses continents, meets with iconic writers and rulers, and changes genders from male to female.

“The sort of overarching narrative of the movie is something I think a lot about with the collections,” says Altuzarra. Orlando was a touchpoint for his spring/summer 13 collection, in which workwear elements were refreshed with elegant, feminine tailoring. The film’s influence is perhaps more keenly felt in Altuzarra’s fall/winter 17 offering, which brings to mind the resplendent Tudor dresses and adornments found in its earlier scenes.

The book is based on Vita Sackville-West, an aristocratic poet, novelist, and horticulturalist who Woolf counted as her close friend and lover. Sackville-West was raised on a palatial estate that had been granted to her family by Queen Elizabeth I. Yet, as a woman, she could never legally own or inherit this home. Orlando playfully reimagines Sackville-West’s noble lineage and, in the process, powerfully interfaces with the implications of gender roles and class structures. Woolf herself described the work as “an escapade” — “half-laughing, half-serious: with great splashes of exaggeration.”

Adapting such an ambitious (not to mention incredulous) work of fiction into a fresh and cohesive piece of cinema is a tall order, even today. But in the 1980s, when filmmaker Sally Potter was pitching the project, it seemed unthinkable. One film exec told the British director that Orlando was “unmakeable, impossible, far too expensive, and anyway not interesting.” But, driven by the story’s unique sense of liberation, Potter undertook a four-year, cross-continental production that changed the possibilities of what a period piece can be and do.

“My desire to break from ‘heritage cinema’ (or ‘bonnet pictures’ as they are often called in private conversation) meant taking a lot of risks,” Potter noted in the film’s press notes. “It would have been a disservice to Virginia Woolf to remain slavish to the letter of the book, for just as she was always a writer who engaged with writing and the form of the novel, similarly the film needed to engage with the energy of cinema.”

To Potter, cinema’s energy is pragmatic. So she simplified the storyline and refocused the picture’s ending — cutting away elements that color Woolf’s text, but do not directly propel her protagonist through history. Potter sought a similarly driven approach in the film’s visuals. Each century has its own distinctive color palette: “the regal Elizabethan periods are done in reds and golds, the winter scenes on the Thames are washed in silver and blues, the Victorian period in misty greens and purples, the 20th century in metal and plastic.”

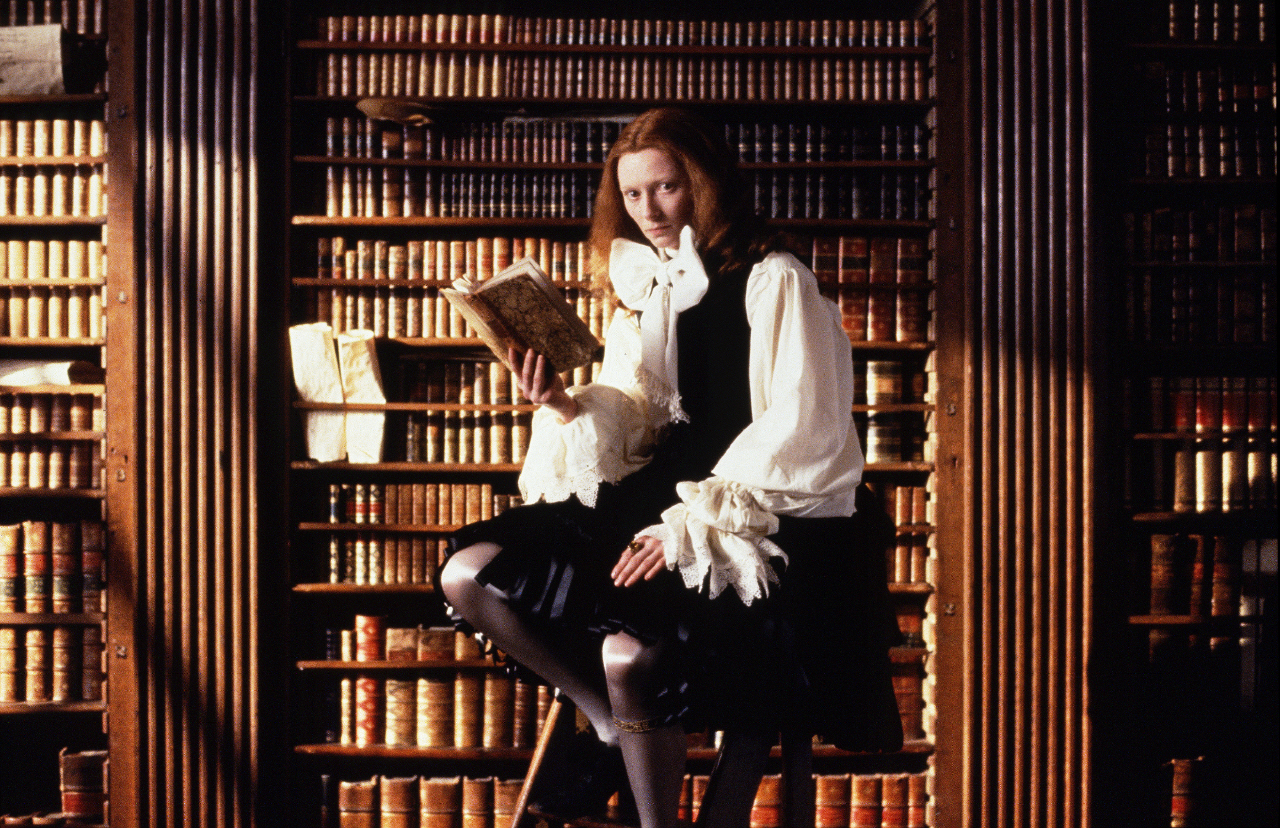

To bring this elegant yet unconventional period adaptation to life, Potter teamed with two female forces in experimental British film: Tilda Swinton and Sandy Powell. We now know them both as Academy Award winners, but at the time, the actress and costume designer were both collaborators of Derek Jarman who cut their teeth on historical projects such as Caravaggio, The Last of England, and Edward II.

In a brilliant Slate piece published at the time of its re-release in 2010, Dan Kois asserted Orlando‘s enduring “influence is still being felt — not only because its mix of the ornate and the offhand has become so prevalent an aesthetic in the indie world, but because its behind-the-scenes artists, all of them veterans of Britain’s 1980s experimental-film scene, have filtered into the mainstream.” Later in the piece, Kois doubled down on his first point: “You can see the impeccably-designed vignettes of Orlando in Wes Anderson’s filmed dioramas, or in Sofia Coppola’s new-wave Marie Antoinette. Without Orlando, would Todd Haynes have been able to make his arch, stylized masterpieces Far From Heaven and Velvet Goldmine? (Costumes, natch, by Sandy Powell.)”

Altuzarra, too, views Orlando as anything but anachronistic. “There’s very interesting gender play in the movie,” he explains. “It brings up a lot of questions and a lot of issues which are really relevant today.”