Kansai Yamamoto selected one of his most demure suits for his latest trip to New York. It’s fitted, graphically patterned, and flecked with bright gold. The revolutionary Japanese designer — now 74, but going on 17 — might be even?more attracted to flamboyant outfits than David Bowie himself. Yamamoto began collaborating with The Starman after witnessing him emerge from a disco ball on a trip to New York back in 1973. The following day, the two men managed to meet, just before Bowie went on stage for a second performance.

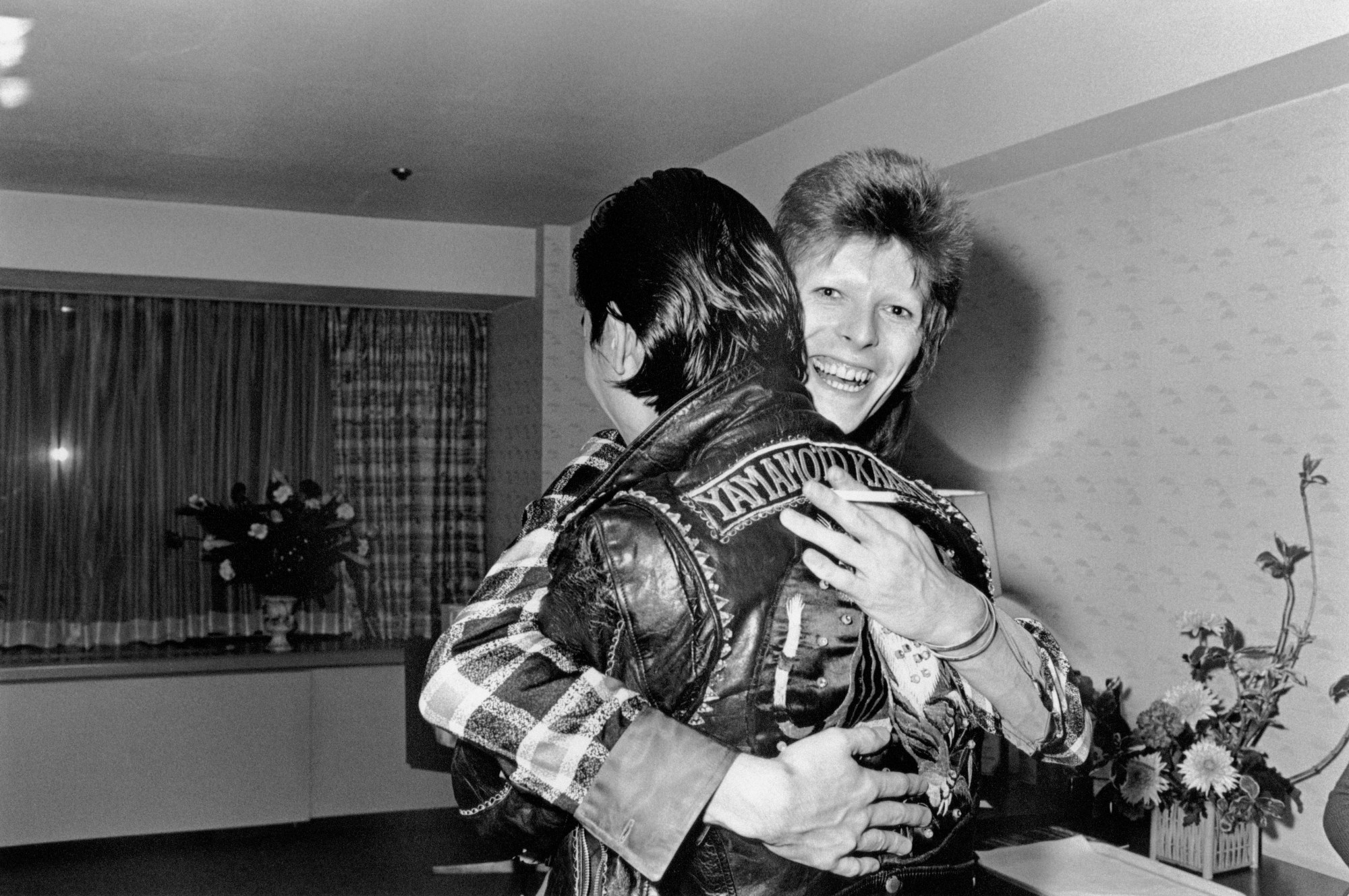

During a talk at the Brooklyn Museum last night with Vanessa Friedman, Yamamoto showed the audience a black-and-white photograph of that initial meeting. He thought Bowie was wearing an orange coat. He recalled his own look more clearly. “I think you can see I’m wearing a belt,” Yamamoto deadpanned, referring to a hefty studded leather design that would have Tommy Wiseau salivating. He casually explained it was actually a collar for Shibu or Akita Inu dogs. “This is just what I wore from Tokyo.”

Yamamoto and Bowie might have one of the most unique working relationships in modern creative history. The designer can’t name a single Bowie song — though he knows there’s one about a rocket that goes up and comes down. It does not pain him, Yamamoto claims, to go one whole week without listening to music. But color is his lifeline. “Color is like the oxygen we are both breathing in the same space. A world without color does not exist,” he said. “When I see the sun rise from the horizon, I see music.” In the early 70s, Yamamoto would frequently accompany Bowie to Kyoto, the traditional Japanese temple city that was Bowie’s favorite. “David was always reserved, but would flip on a switch and become David Bowie,” he recalled. “Myself, I am always Kansai!”

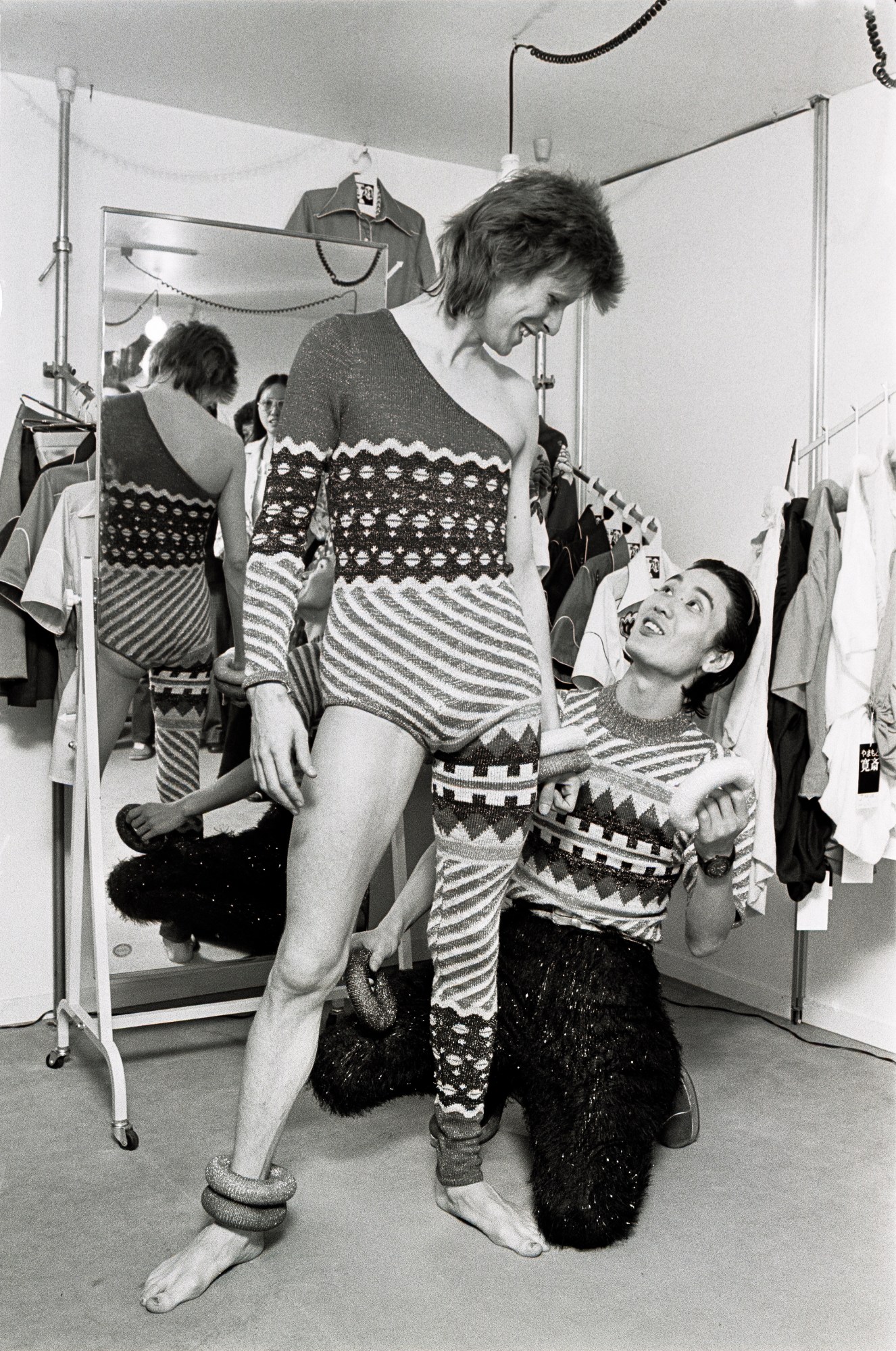

It’s his relationship with Bowie that has seen Yamamoto thrust back into the Western consciousness. His name isn’t one that first comes to mind when thinking of influential Japanese designers like Yohji, Issey, or Rei. But he’s responsible for one of the most iconic costumes ever: the balloon-legged vinyl jumpsuit Bowie wore on the ‘73 Ziggy Stardust tour, which now forms the centerpiece of the exhibition David Bowie Is. It was Yamamoto, naturally, who first introduced Bowie to the kabuki aesthetic that defined the singer’s style from the Ziggy era throughout Aladdin Sane. “My understanding of Western style comes from David Bowie,” Yamamoto explained, “and he learned the Eastern style through me.”

The jumpsuit is Yamamoto’s favorite costume he ever designed for Bowie. There’s only one other piece in David Bowie Is that the designer truly loves: the Alexander McQueen Union Jack coat Bowie wore on the cover of his 1997 Earthling album.

Like Bowie, Yamamoto was a pioneer of genderless dressing in a quietly radical way. “When I designed Bowie’s clothes, I approached it as if I was designing for a female,” Yamamoto said. “There’s no zip in the front.” Yet Kansai didn’t really know what to make of the West’s affinity for blurring gender lines in the early 70s, an era when the streets of Japan weren’t so friendly towards men in sequins. (Same-sex marriage was simply inconceivable.) Yamamoto said he was overwhelmed by the number of David Bowie Is visitors wearing unconventional, gender-blurring outfits. “To see the younger people dressing the way they do is a victory.”

Outsized, blown-up shapes are a hallmark of Yamamoto’s ouvre, and not just when it comes to fashion. Towards the end of his talk he pulled up a photo of one of his most elaborate stage settings, featuring an enormous inflatable whale suspended in the air. “I’m the top in my own company and I don’t own a car. But I own a 35-meter air balloon — two of them,” he said, more finishing on a more poignant note: “To have Bowie sit atop those air balloons, and have him sing his songs, was my dream.”

So is Yamamoto finally getting to retire? Hardly. Next up for the designer is a trip to the North Pole. He wants to find inspiration for an ice-themed show he’ll stage in New York or London in two years time. Requesting, to the horror of the Brooklyn Museum’s lighting technicians, that the auditorium’s lights be turned onto the audience, he offers some words of advice to the many young fashion students in attendance. (Yamamoto is self-taught, and submitted his work for a prestigious Japanese fashion award every single year until he finally won the thing.) “Fashion is not a profession I would recommend. But even if people tell you that, if that’s what you want to do, please do it.”