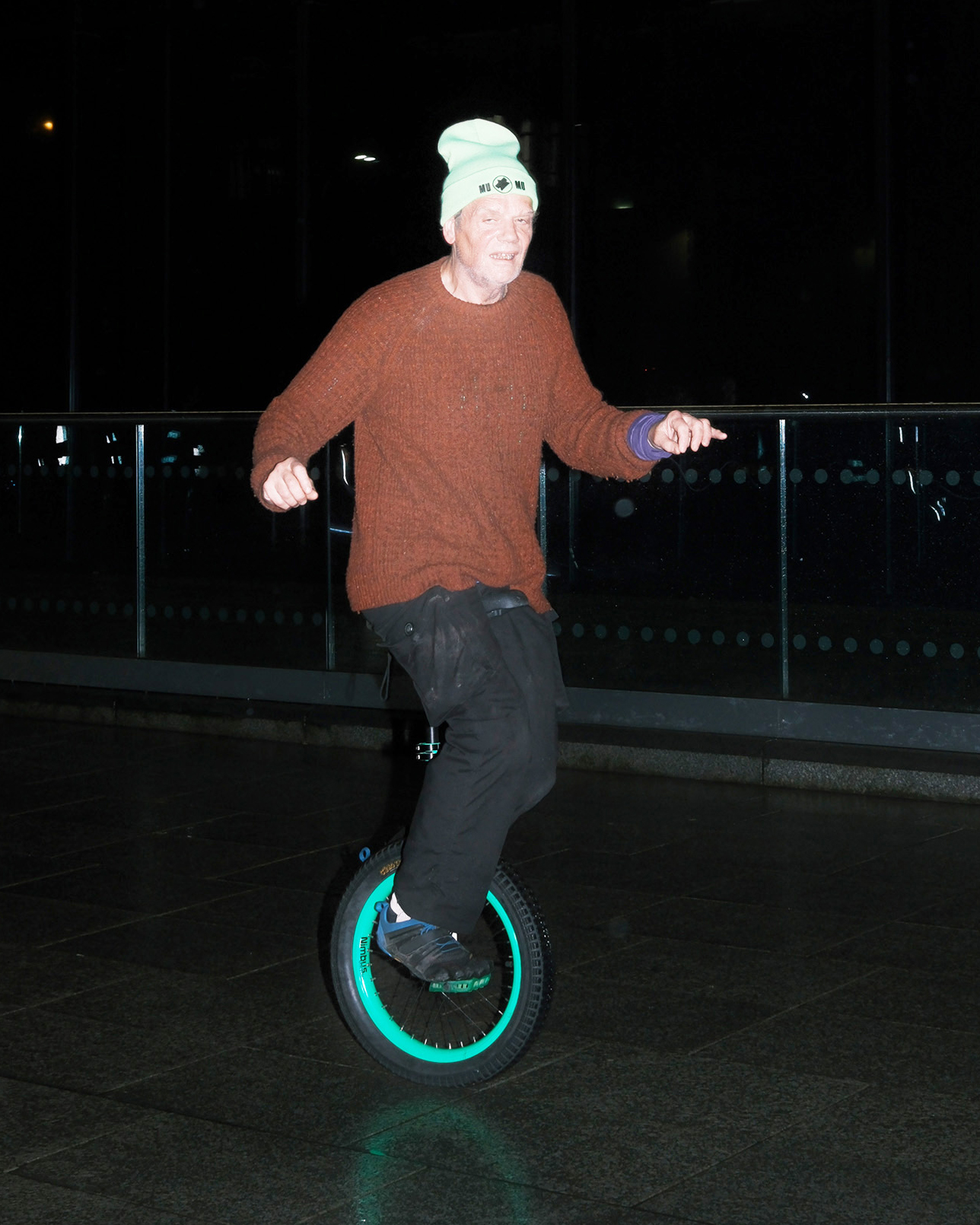

“What’s all this about then?” a man on a bicycle asks me. It’s a fair question, given that I’m one of 400-odd people blocking the main road, dressed variously in hi-vis overalls, psychedelic ghillie suits and sinister papier-maché masks. Confused shoppers look on as we march through Liverpool city centre waving neon-lit totem poles, banging drums, blowing on discordant foghorns and shouting about death. “It’s sort of a funeral,” I try to explain, “but not really.”

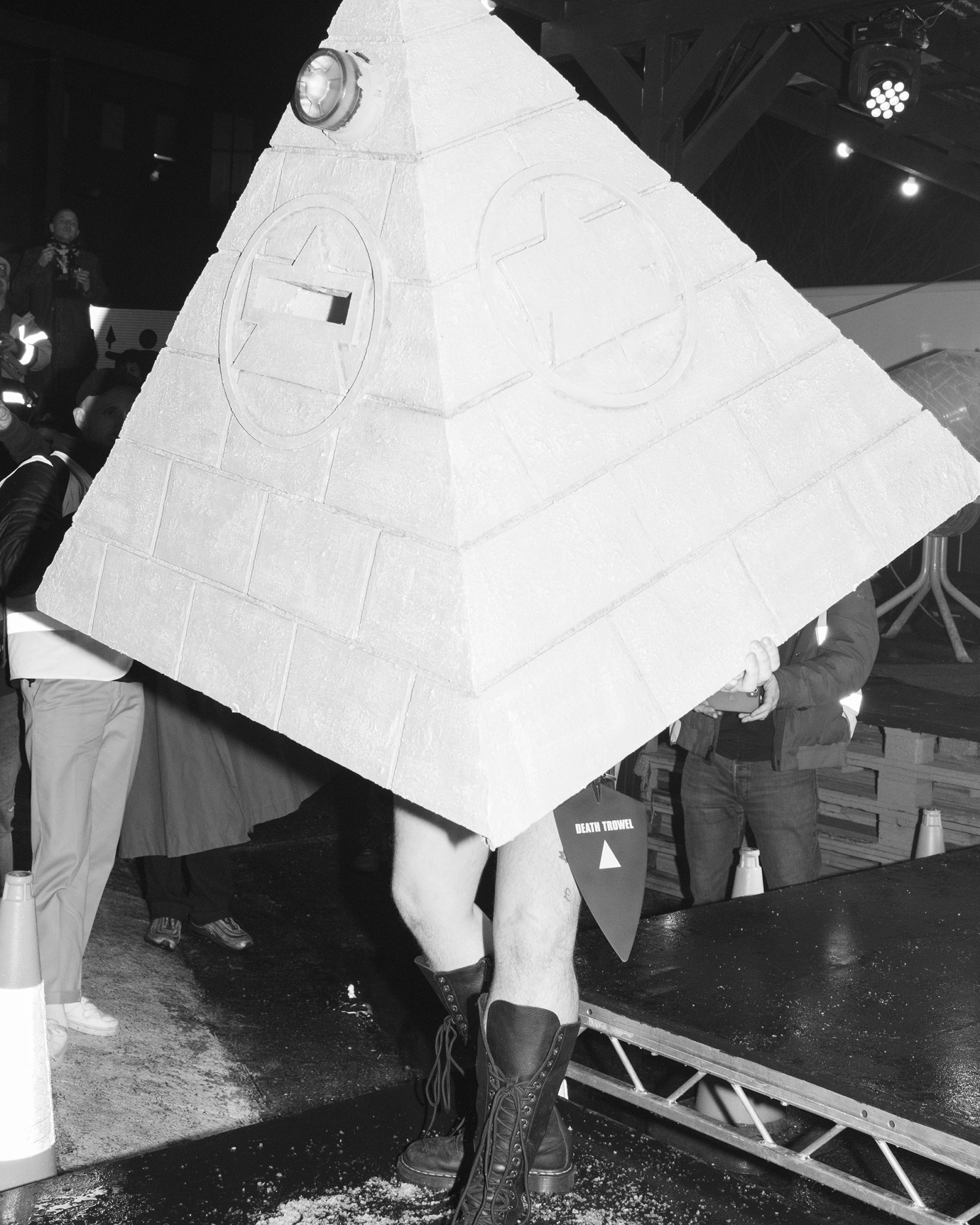

My efforts fail to capture the overwhelming strangeness of the People’s Day Of Death: a public ritual created by art-pop provocateurs the KLF as part of their plans to encase the ashes of 30,000 people in a gigantic brick pyramid in the Wirral. Described as “a ceremony to honour the dead and a celebration of life,” it’s part funeral march, part art happening, part club night, and part fashion show — co-curated this year by renegade clothing brand Sports Banger.

All of this aligns with KLF members Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty’s penchant for riotous cultural mischief stretching back almost 40 years, from quitting the music industry by machine-gunning the Brit Awards audience (their use of blanks one of very few concessions to social etiquette) to burning a million pounds on a remote Scottish island. Today’s events are an evolution of the Toxteth Day Of The Dead held in 2017, at which Drummond and Cauty returned from 23 years of self-imposed creative exile: the first cohort of “brick-bearers” paid for their loved ones’ places in the pyramid by bringing Drummond a stolen shopping trolley.

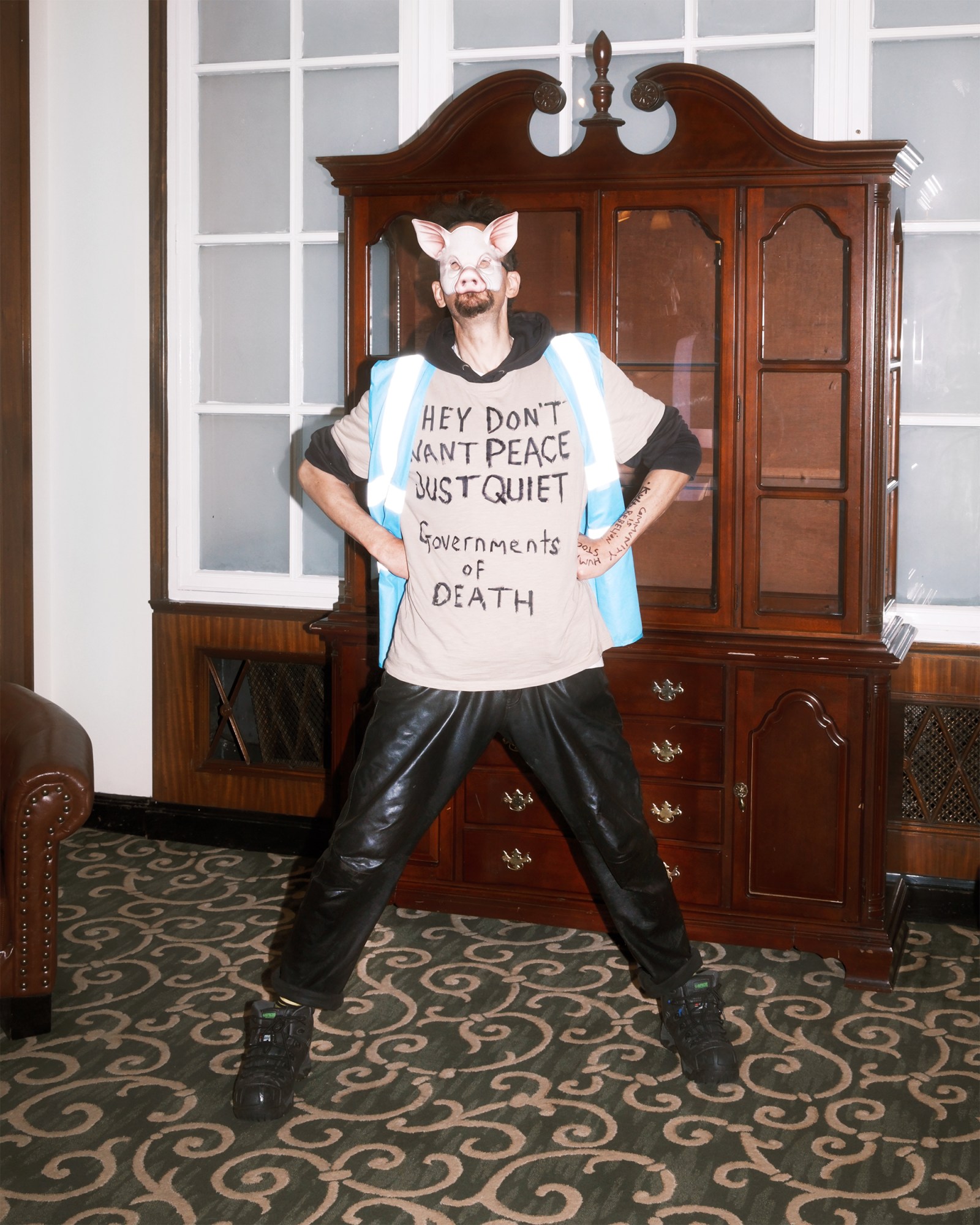

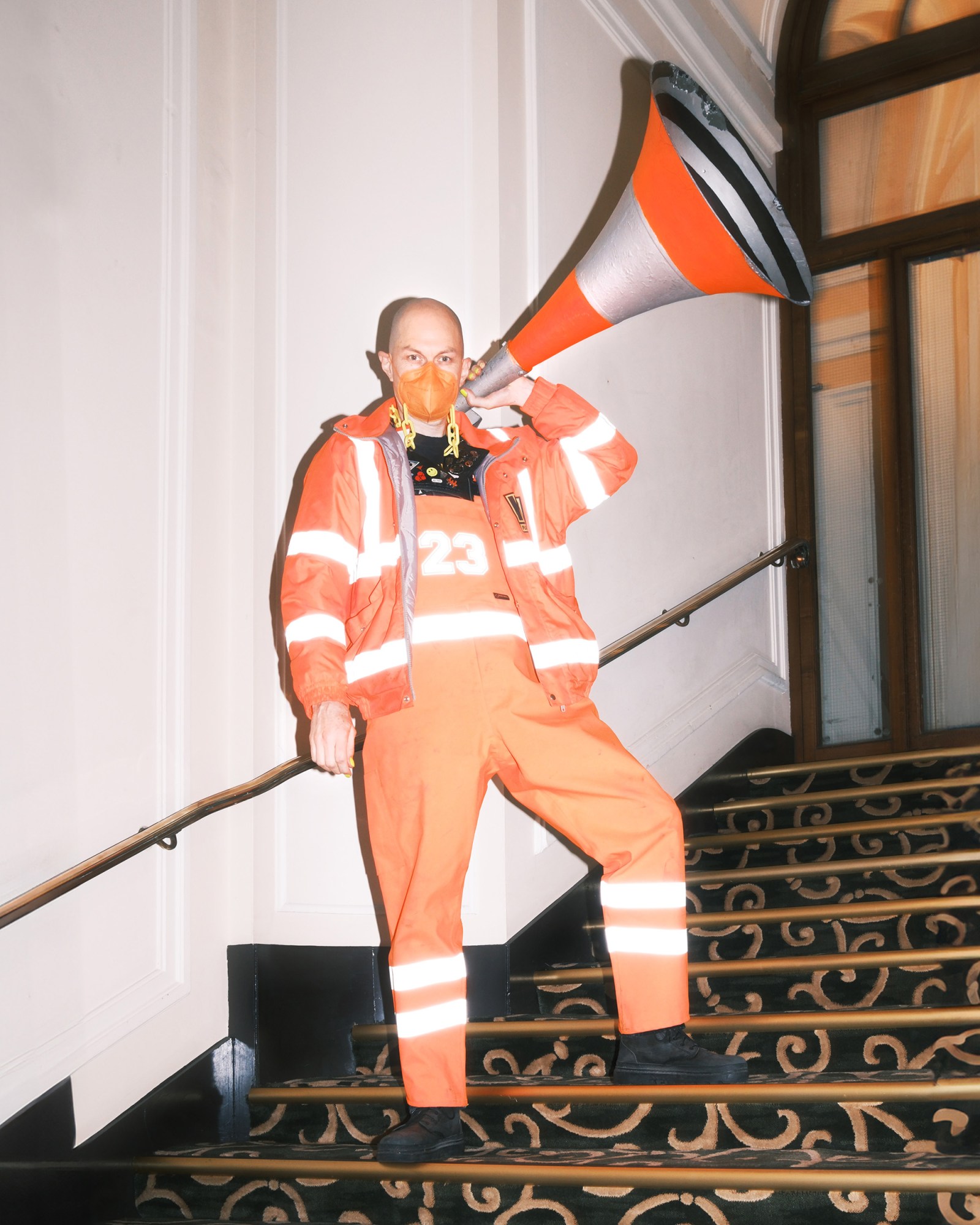

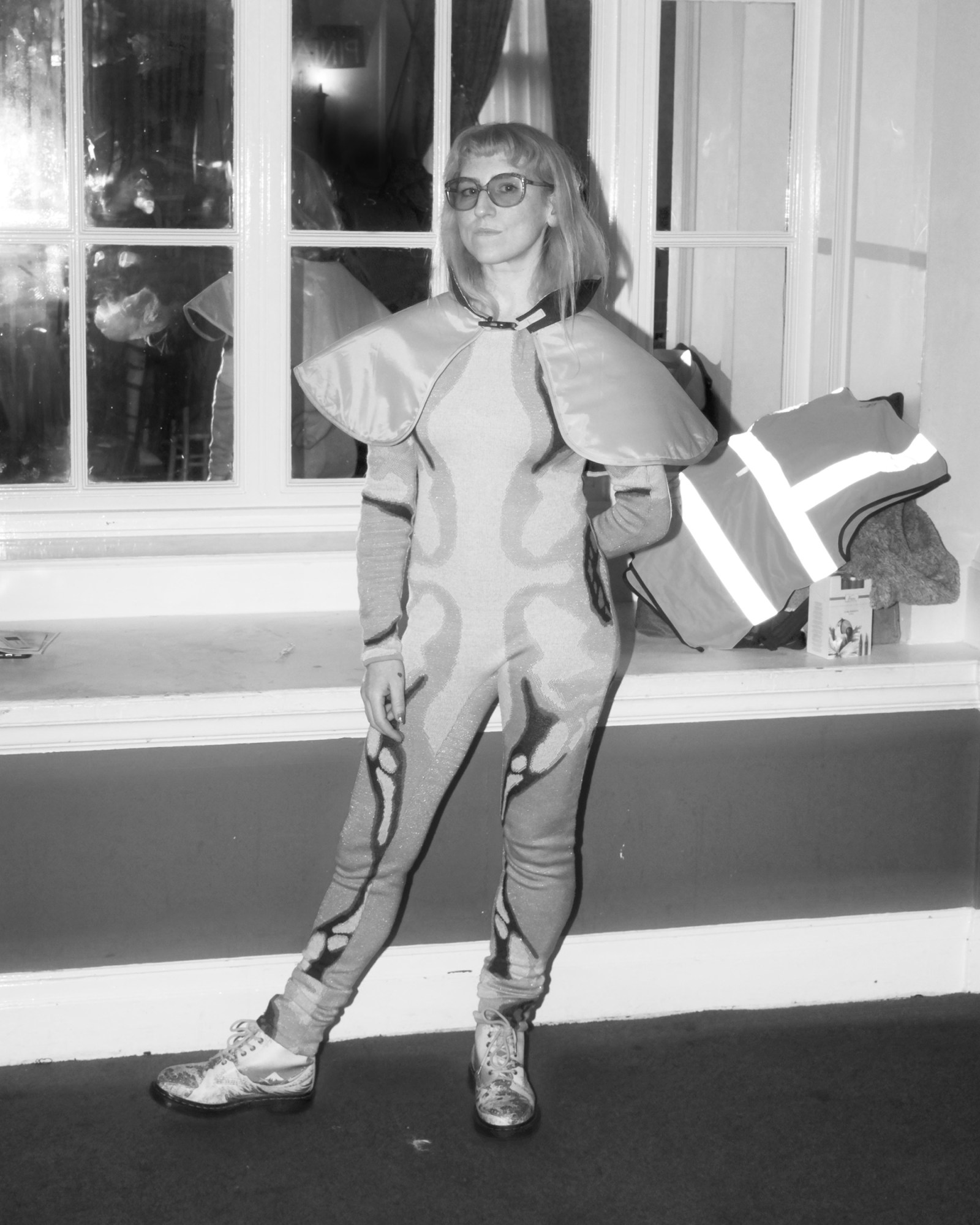

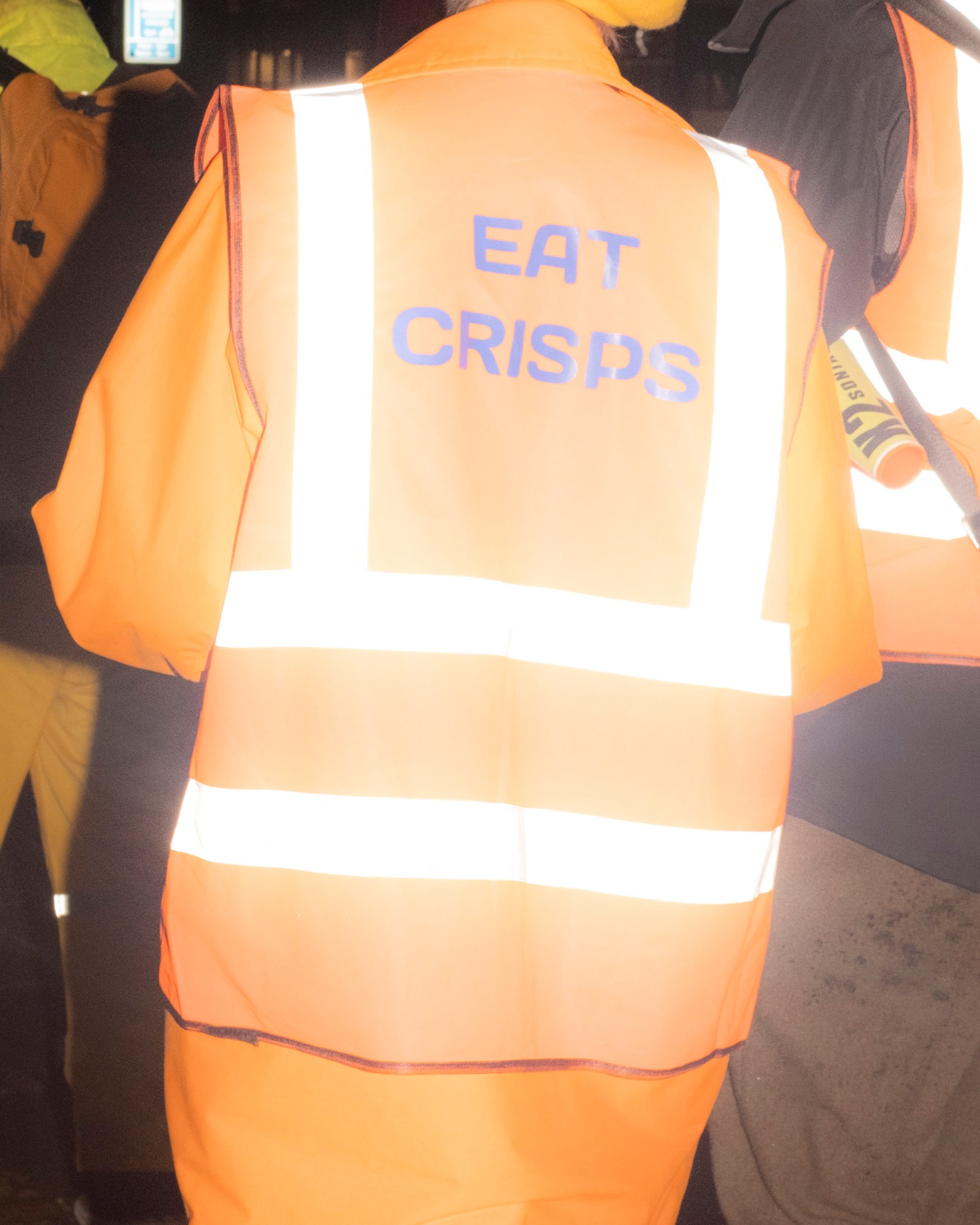

With the People’s Day Of Death now an annual fixture held every 23rd November (the number 23 is a recurring motif in the KLF mythos), we’re summoned to assemble in the faded grandeur of the Adelphi Hotel at precisely 12.23pm. On arrival, we’re tasked with joining one or more Skools, each responsible for creating the ceremony to follow: the Skool Of Horns build vuvuzela-esque foghorns out of balloons, glue and plastic plumbing tubes; the Skool of Katwalk recruit the evening’s cast of models; the Skool Of Truancy have failed to turn up. Four hours later, we convene in the foyer, 400 dayglo freaks wielding crude musical instruments and lanterns, overwhelmingly conforming to the “hi-vis, high fashion” dress code. Attendees at the Adelphi’s other two events, the Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation’s Strictly Come Dancing Charity Fundraising Gala and a wedding, look at us askance.

We begin the funeral procession by stepping out into the road and demanding that the traffic stops for us, our horns blaring. No formal clearance has been sought for this: “fuck permission” I’m later told by Tommy, the puckish figure in a lion-tamer’s jacket and top hat who’s led these marches since 2017. It encapsulates in a moment the irreverent and gently rebellious tone of proceedings: the collective mischief of an illegal rave or unsanctioned protest, rewiring our staid Victorian notions of what death rites should look or feel like.

Later, as we wait at the ferry terminal, I speak to Ed and Scott: the latter holds a brick with a small recess containing the mandated 23 grams of their father’s ashes. “He would have loved this,” Ed says. “He was really into art and alternative thinking. We did a traditional funeral but even then you don’t know everyone there. We’re amongst strangers here, but you don’t feel alone.” As the other brick-bearers receive their bricks, the mood shifts from raucous and celebratory to something more contemplative. “It comes in waves” says Scott of his grief: his father died 10 years ago, but when he and Ed came to a previous ceremony they knew this was the right use of the remaining ashes.

We cross the water in complete silence, waves gently lapping at the side of the hull, the Mersey transformed for a moment into the River Styx. The names of this year’s 26 dead are read solemnly over the tannoy. “Don’t be afraid of anything, ever,” we are told, “because you are already dead.” When we reach the opposite dock, we shout the names of those we’ve lost into the wind and rain of Storm Bert. I turn to a friend, and find they’ve been completely overcome with emotion.

We march on into the night, through light industrial units and the formerly prestigious Georgian squares of Birkenhead, until we find ourselves in a small concrete forecourt with a soundsystem, a stage and a cement mixer. Each of the dead are called in turn: some brick-bearers hold their bricks aloft, others give them a farewell kiss. Ed and Scott perform an awkward but wonderful ritual of their own devising, circling their way forwards while holding their brick between them. When one woman hesitates, Tommy puts an arm around her and they walk together. Each name is cheered with foghorn blasts and joyous, mournful howls. An undertaker reads brief eulogies as the dead are cemented into the small but growing People’s Pyramid: some are poetic and poignant, others hilarious. The point at which I finally lose it, and join those around me crying openly for a collection of total strangers, is when one eulogy reads in full: “My dad.”

Then, after death, comes life. Within minutes of people sobbing uncontrollably, and in some cases while they’re still doing so, I’m watching Sport Banger’s newly-recruited models walk the runway in KLF-branded cagoules, a couture-ified bright yellow bodybag, and a gigantic model of a pyramid. They’re accompanied by a bagpiper, a techno striptease featuring prosthetic tits jiggling on a performer’s shoulderblades, a thumping remix of the KLF’s own “What Time Is Love?” and drag queen Sharon Le Grand belting out “Like A Prayer”. Jimmy Cauty appears on the catwalk waving a massive replica of the bricks in which people have just been interred. It’s an absurd and chaotic mix of imagery and emotions, but makes perfect sense within the anarchic, improvisational world of both the KLF and Sports Banger. It also feels like a far truer reflection of the messy, occasionally hilarious realities of life and death than the dry formalities of a “normal” funeral.

The rest of the night is soundtracked by DiY Soundsystem, playing bass-heavy deep house from a disused ice cream van. Their presence brings things full circle: in 1990, Cauty handed them the first demo tape of “What Time Is Love?” to play at Glastonbury, helping to kickstart the illegal free party scene. Today one of DiY’s founding members, Simon “DK” Smith, is added to the pyramid. Dancing in such close proximity to death feels weirdly freeing, as if running today’s emotional gauntlet was our price for accessing the cathartic release of the dancefloor. “I still go to fashion shows or big clubs and squat raves, but it’s not the same” says Jonny from Sports Banger: he came to last year’s event on a whim, and ended it shaking Cauty and Drummond’s hands and agreeing to help run it next time. “This is the only way I get a buzz now.”

Words: Ed Gillett

Photography: Sam Hutchinson