This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Out Of Body Issue, no. 367, Spring 2022. Order your copy here.

In 2019, Irish hip-hop trio Kneecap took to the stage at Body and Soul, an independent music festival in Westmeath, Ireland, playing to a sold-out crowd of fans. That’s no mean feat for any new act, but especially for this 10,000 strong crowd, who are all singing the band’s lyrics back to them – predominantly in Gaeilge. In a video posted to YouTube ahead of the gig, the band joked that every Irish speaker in the country must be there.

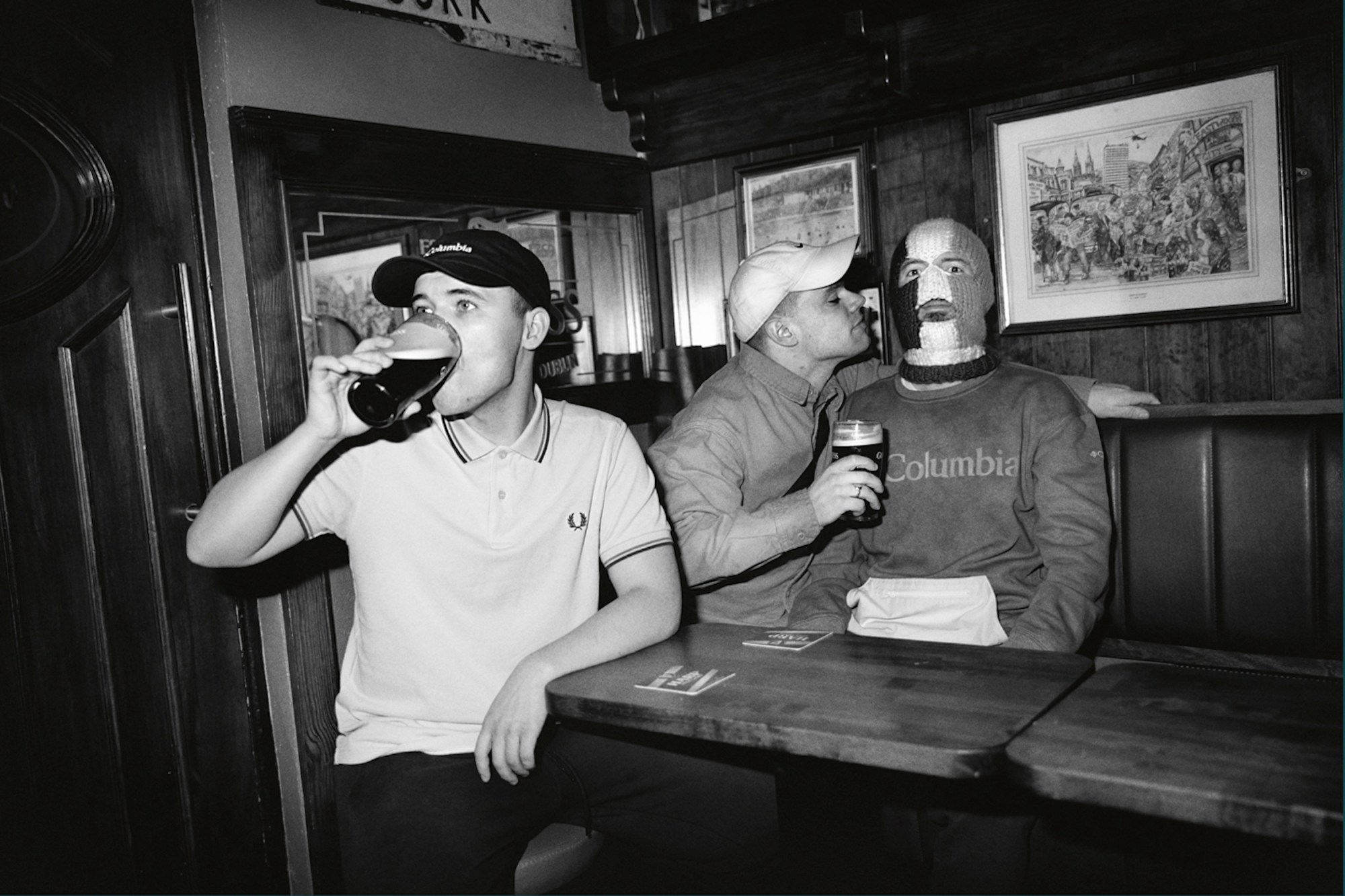

While, in the Republic of Ireland, mandatory education programmes mean that most people leave school with at least a basic grasp of the language, in the north, where the band are based – frontmen Móglaí Bap and Mo Chara are from Belfast and the balaclava-wearing DJ Provaí is from Derry – the picture is murkier. The Irish language is seen as a controversial issue in Northern Ireland, and a recent move to give it protected status led in no small part to a complete breakdown of Stormont, Northern Ireland’s parliament, for several years. For Kneecap though, their use of language isn’t political – it’s instinctive.

The group are Gaeilgeoirs – native speakers who revert to Irish when talking to their friends and family – and so, naturally, they write and rap in the language they speak. While their origins might indicate otherwise – the group supposedly began when Móglaí Bap fled arrest after spray painting “Cearta” (a reference to Irish language rights, and also the name of the first single) in Belfast the day before the Irish Language Act march in May 2017 – their music is not created to make a point. It’s created for people to get on it.

“Irish is less of a subject for us, and more of a living thing,” Móglaí Bap explains. “We’re not on a three-man mission to try to save the language,” Mo Chara interjects. “People always ask us that, but it’s not really what we’re here for. We’re here for tunes and a big fucking party. If that comes with it, then happy days.” It’s that spirit that makes Kneecap so exciting and so beloved both in their hometown of Belfast and beyond. Their gigs have far more of a debauched, raver energy than anything akin to a lecture hall or a protest. Their lyrics, while in Irish, are interesting – not because they’re in Irish, but because they’re catchy and clever.

So, while Kneecap’s music might be intrinsically linked to the political status of the Irish language, their music is personal, not political. They make stuff that sounds like what they like – Kneecap’s lyrics might sound lifted from an Irish folk song, but the beat and cadence is infected with old school 90s hip-hop. Their later tracks are more heavily electronic rap; a faster, more frenetic Kojaque, maybe, or a staccato Slowthai.

It’s genre-bending party music which reflects their reality as young people in Belfast (“We’re at the afters and it’s a disaster / Cunts are talking politics, there’s a lack of a laughter” Mo Chara raps on the anthemic Get Your Brits Out). And, despite the north’s outsized reputation for musical talent (albeit often in a boomer-y way: Ash, Snow Patrol, Stiff Little Fingers, noted anti-vaxxer Van Morrison), they’re the first in a while to do that, and certainly to do it so well.

“We’re not on a mission to try to save the Irish language. We’re here for tunes and a big fucking party.” Mo Chara

But, considering the climate they inhabit, it’s perhaps unavoidable that the band’s rise to fame has been tied to politics. They have been banned from playing at University College Dublin – an incident that led to them later penning the anti-security track Bouncers – and banned from RTÉ, the Republic of Ireland’s national broadcaster, which they appealed on the basis that their music was satirical, and “a caricature of life in west Belfast” for young people.

They have been attacked by the conservative Democratic Unionist Party for inciting anti-imperialist chants at a venue in Belfast, which had hosted Prince William and Kate Middleton the night before their gig (this led to the anti-DUP techno-lite earworm Get Your Brits Out). One line in their song C.E.A.R.T.A – “Raithneach dhleathach in focain Éirinn Aontaithe” – translates to a call for the legalisation of weed in a United Ireland. It has not been a quiet one, lads.

Even the band’s name – a reference to paramilitary kneecappings – leaves some uncomfortable, but that discomfort perhaps speaks to a generational gap of criticisms sometimes levied against them. They are of the ceasefire generation: a moniker applied to post-conflict children born in Northern Ireland in the aftermath of The Troubles and 1998 Good Friday agreement.

They’re also part of a global culture of young people who are marked by their ability to find humour in absurdity, who make memes of divisive politicians and detooth their most aggressive stances through viral tweets. “Now people expect [our performances] to be a bit tongue-in-cheek,” Móglaí Bap says. Accordingly, bouncers are less problematic than they were in the early Kneecap days; they “love the craic we bring to the stage now”, Móglaí says.

Plenty of their fans don’t seem to care, either. Many sing along to Kneecap songs with no grasp of the Irish language, in the same enthusiastic fashion others might to BTS or Rosalía: they know their faves don’t need to sing in English to have songs that slap. “The subjects of our songs might be specific to where we live but they’re very universal too,’ Móglaí says. “Even if you don’t speak any Irish, you can enjoy the music and not feel guilty about not being able to speak it.”

“Even if you don’t have any Irish roots, there’s an anti-establishment message there that people can instantly connect with,” Mo Chara adds. One thing is for sure: Kneecap certainly don’t need to wait for those lost in translation to catch up with them.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on music.

Credits

Photography Rich Gilligan.

Post production Jamie Saunders.