Poor housing conditions have plagued Britain for centuries. In our modern world, little has changed for the better for the nation’s poorest. In 2013, shelters reported that over 975,000 children were living in “bad, overcrowded” social housing. Less than a decade on, the issue has become far worse. NHF‘s housing needs report, published in December last year, found that up to two million children currently are living in overcrowded and unsuitable living conditions in England — a fifth of all children. The deepening crisis is hardly unsurprising after decades of underfunding through austerity politics ushered in by successive Tory governments, and with the pandemic and rise of living costs going up, it’s only set to get worse. If you are black, brown or working class, then it is likely that you or someone around you will be on the front line of this issue.

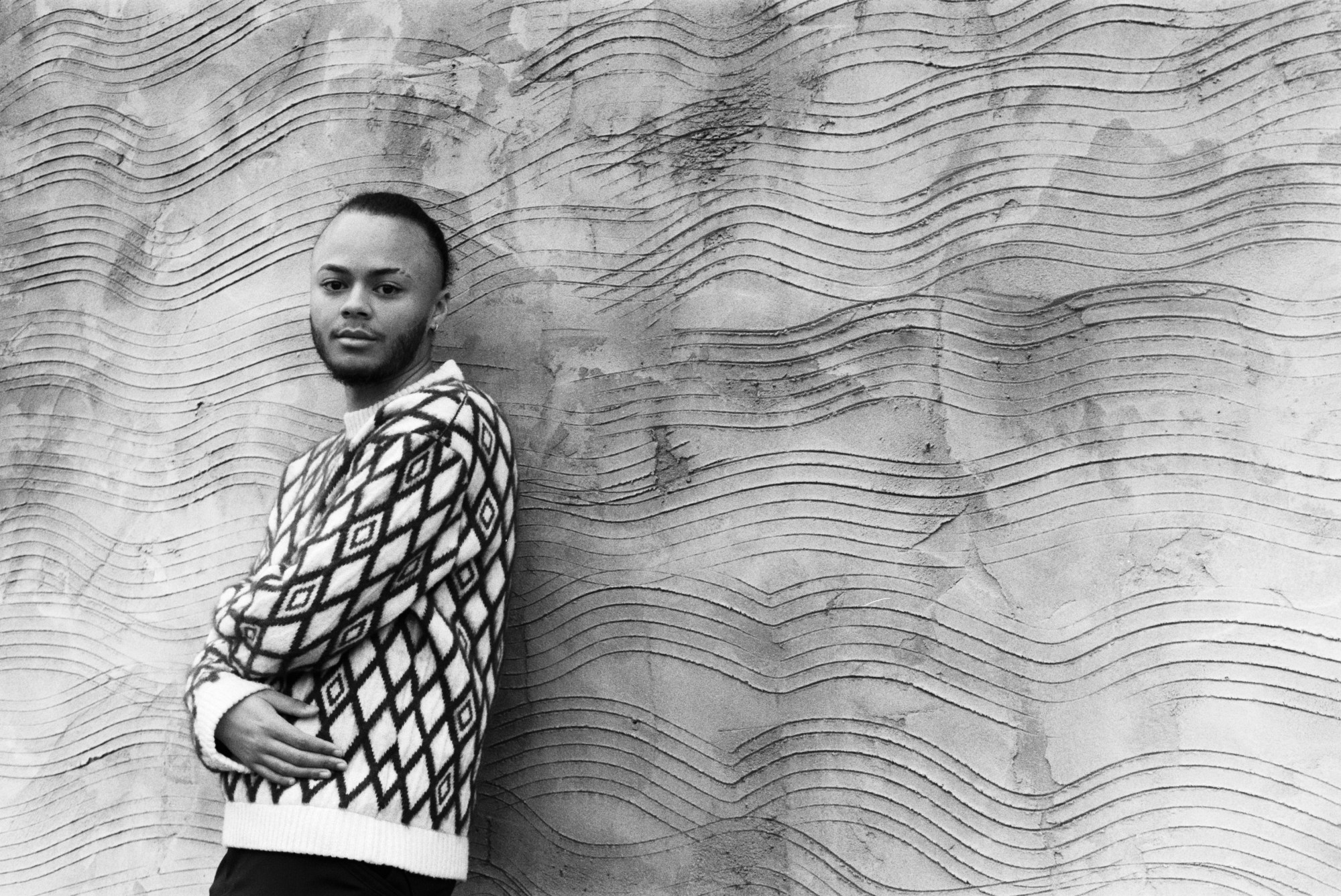

But a new generation of young activists are determined to change that. Kwajo Tweneboa, one such campaigner, has made a name for himself as one of the most prominent voices on the ground by meeting social housing tenants and bringing to light the derelict conditions they have been forced to endure. He is working to make sure hope lies at the end of the tunnel.

And at only 23 years old, Kwajo has become something of a hero for social housing tenants, making BBC headlines for his wins against the housing giants. His social media campaign shamed Clarion, Europe’s biggest housing association, into making much-needed repairs on a property him and his two sisters were living in on the Eastfields Estate in south London. The property had no ceiling in the main room, mould, asbestos, a rat infestation, and water pouring through electrical fittings. After 18 months of unanswered calls, Kwajo took to Twitter to share pictures of the shocking conditions.

Once the public shaming Clarion sprung into action, Kwajo continued to post videos from the dilapidated properties of different tenants, exposing housing associations and criticising those in power who have neglected tenants for too long. “I simply just had enough”, he says. “I was in social housing since I was a child. I’ve lived in temporary accommodation, a cold, damp converted car garage that still had a garage door on it and other living arrangements that no one should have to go through.”

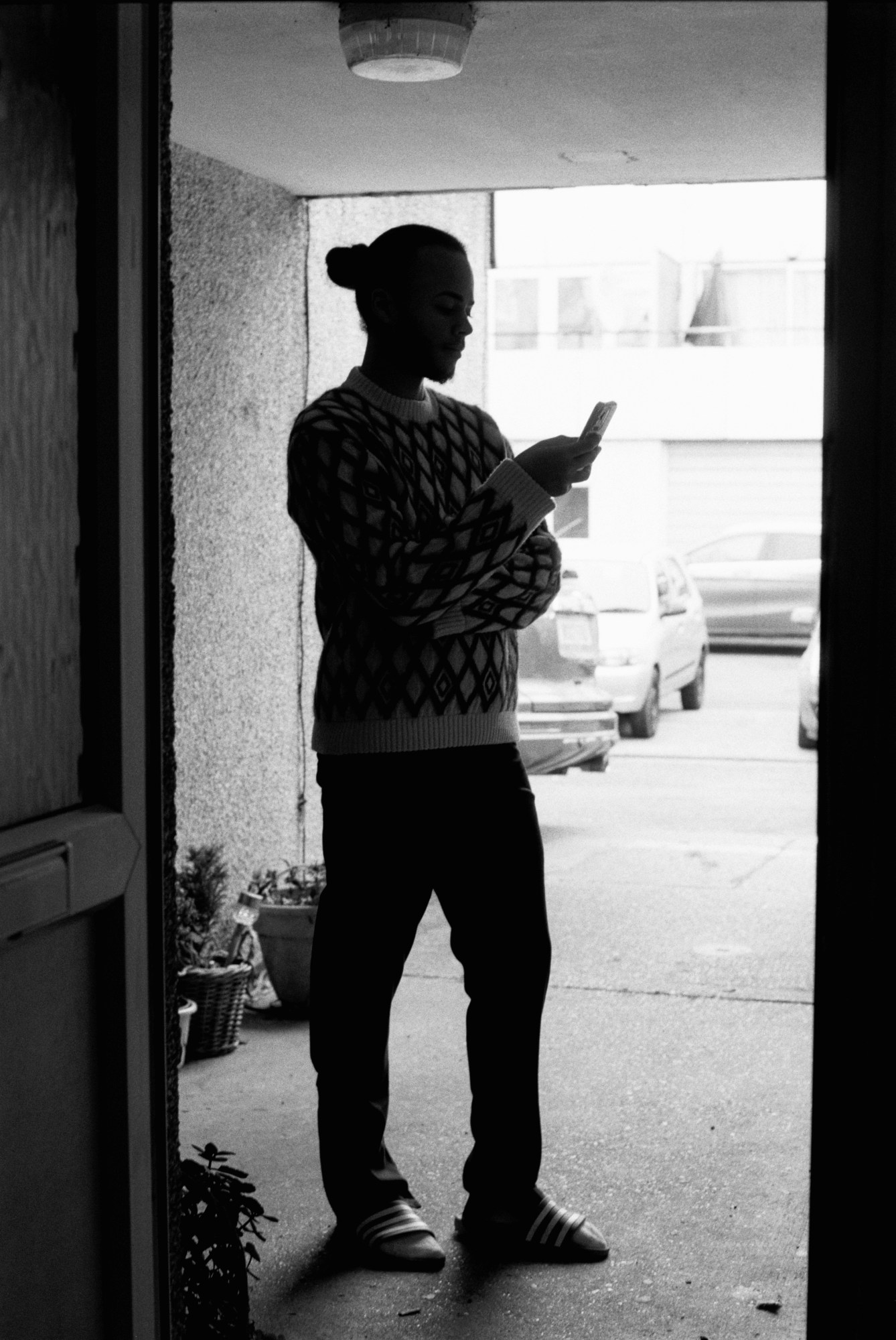

Most people spend their rainy Sunday afternoons relaxing, but today Kwajo is travelling across London to meet social housing tenants with first-hand experience of the living conditions he is passionately grappling against. Kwajo is talking Zoom from outside Tooting Broadway Station. “Today, I’m going to go see a tenant that lives in Ealing and then another one on the other side of London,” he says.

Despite his age, he speaks with the air of a wise community elder. He remains both humble and grateful for the community that helped raise him. “I have some very special people, from friends to family members, and people that I’ve met along the way who have helped and pushed me to keep going.” Even living on the brink of severe poverty, he still finds glimpses of joy in the struggle. Midway through our conversation, Kwajo and I get lost reflecting on our joint working-class experience — pondering on the “struggle” meals we once had. “Corn beef slaps!” he says. “I haven’t had it in ages, I need to.”

Kwajo was initially hesitant at sharing an honest account of the conditions he grew up in, fearing ridicule and rejection. “I didn’t want to use social media”, he says. “When I was young, I would never talk to my friends about my living conditions and never invite them over to my house. By putting my living situation out there, my friends, family and everyone would see my poor living conditions, conditions that people shouldn’t have to deal with.” But his reluctance to be seen quickly became a thing of the past, as his message started resonating with the public. You do not have to look far for the evidence – Kwajo’s Twitter followers have surged from 5k to almost 40,000 in a matter of months since he became a leading advocate for social housing.

“I took a leap of faith”, he says. “It was a risk, but it was a risk that paid off.” His journey has enabled him to comprehend the wider social and political dilemmas that drive social housing tenants into dispossession and poverty, while also being aware of those in power who disregard them. “The working class and people of colour are left to rot at the bottom and suffer the most for every social and institutional issue we’re currently facing.” He says. “We have elected officials that are failing us – if our MPs cannot provide decent living conditions for all, they should give up their £80,000 job and give it to someone who cares.”

On 22 February this year, following the attention his Clarion campaign brought him – Kwajo met with the Secretary of State for Housing, Michael Gove, to discuss how the lives of housing tenants are at risk. “We discussed tenants being ignored and how housing associations and councils are equally as bad in terms of disrepair,” he says. But despite promises from politicians remaining as yet under-delivered, Kwajo remains optimistic for what is yet to come. “I do appreciate that [Michael Gove] has been the first minister to sit down and have a conversation with me,” he says. “And I do hope that change will happen. I’m sure it will.”

Since then, Kwajo has continued to work with politicians on the issue of social housing in London and beyond. In March, he met with the Deputy Mayor and Mayor of London, where they discussed the poor standards of private and social housing in London, and 15 potential solutions to the crisis raised by Kwajo himself. He is pushing for revolutionary change, where all people are entitled to a decent living space – regardless of their class, race and gender. “I’m winging it right now, but I want there to be reform to legislation and changes in regulations and standards of people’s living.”

But Kwajo isn’t content in leading the way as a lone figure. Instead, he wants to bring up the next generation of housing activists by going into schools and educational institutions to lead young people on the right path to change. “I want to teach others how to advocate for change,” he says. “Because it takes the collective, not the few, to make a change at the end of the day.”

This is the goal of housing activists and community campaigners like Kwajo: to inspire collective action, to affect real and irrevocable change. To do so, we must create a welcoming environment where young leaders can discuss with policy-makers and other campaigners, allowing their ideas to blossom and thrive — thus leaving a blueprint for generations to come. In the meantime, Kwajo is not going anywhere anytime soon. “It has been a hard two years, but the story has just begun.”

Credits

Photography Jay Izzard