There’s a saying in Cantonese that has stuck with 26-year-old documentary photographer Kyle Lui. “It’s kind of an old-school parenting phrase, and it translates to, ‘I have eaten more salt than you have rice (我食鹽多過你食米)’,” he says over Zoom from his home in Brooklyn. “It literally means, ‘I have gone through more hardship than you have’. I don’t think that the phrase is unique to immigrant families, but it speaks to what many children of immigrants hear growing up.”

The proverb inspired the title of his latest multimedia project, Sowing Rice With Salt, which sheds light on the interconnected struggles of children of immigrants by exploring the deeply formative yet often strained relationships they share with their parents. “My rewriting of the phrase refers to the parent who has gone through so many hardships to allow for the success and well-being of their children. This project is about how the child – the ‘rice’, in this instance – is coming to terms with that.”

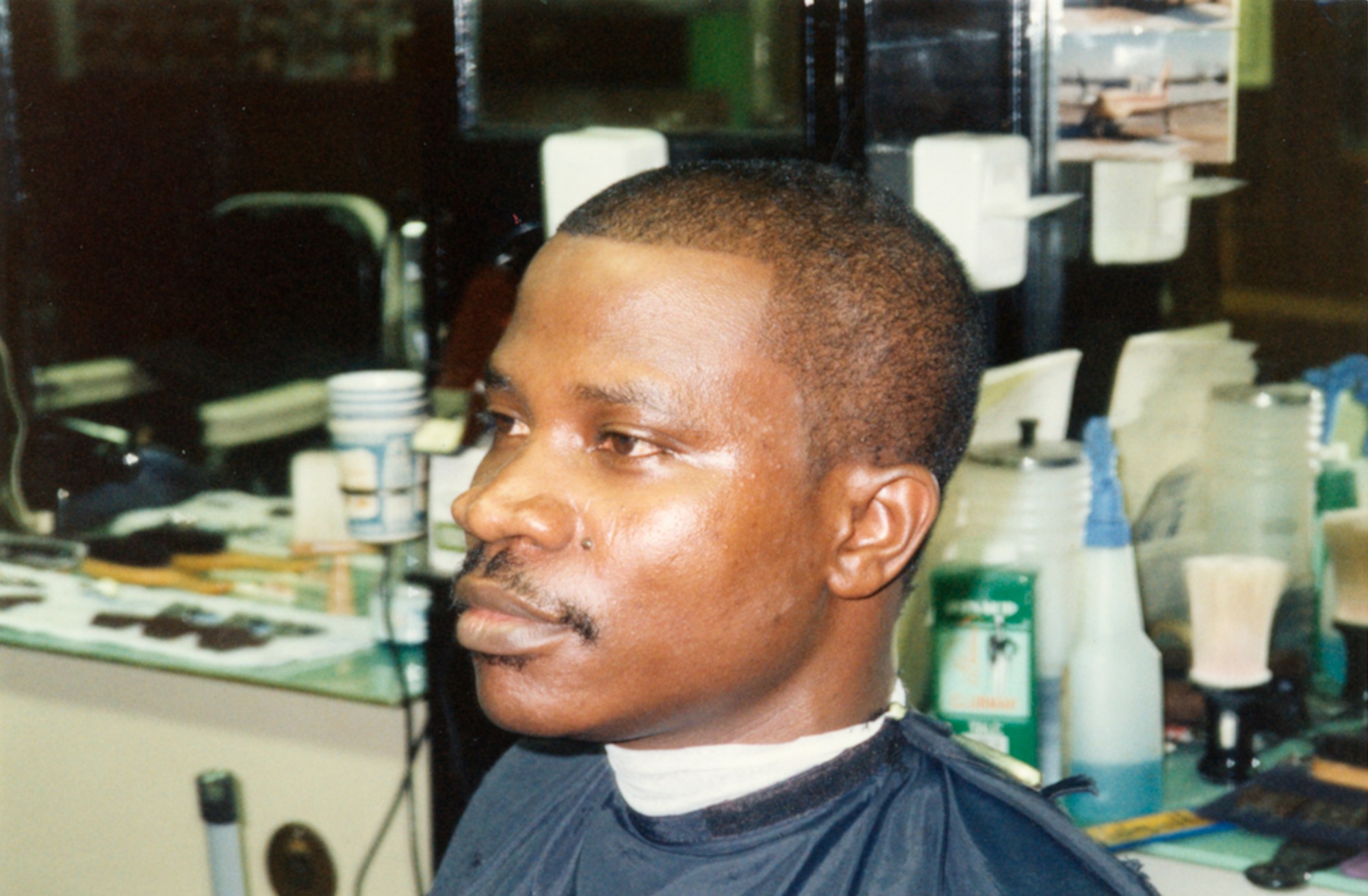

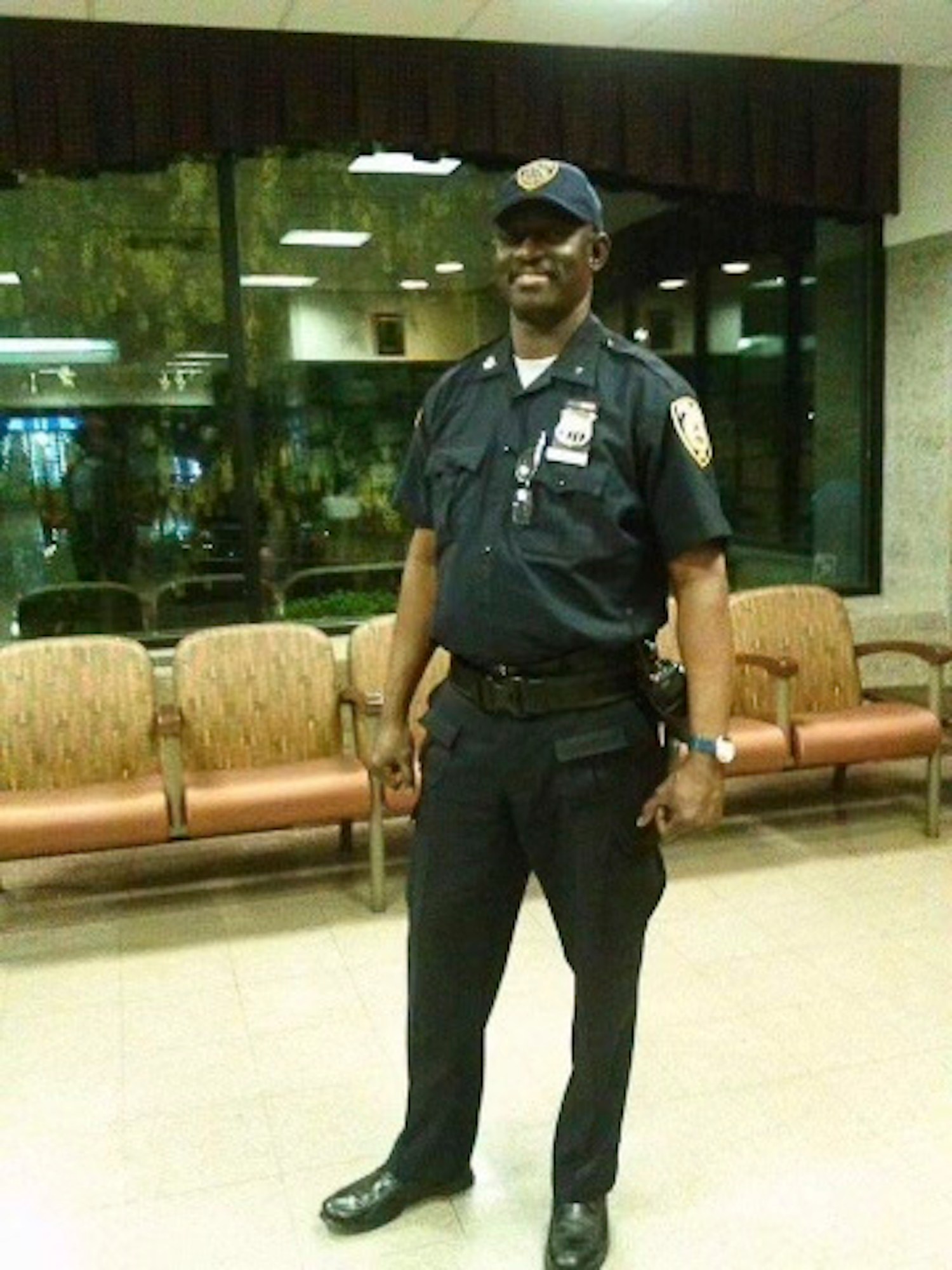

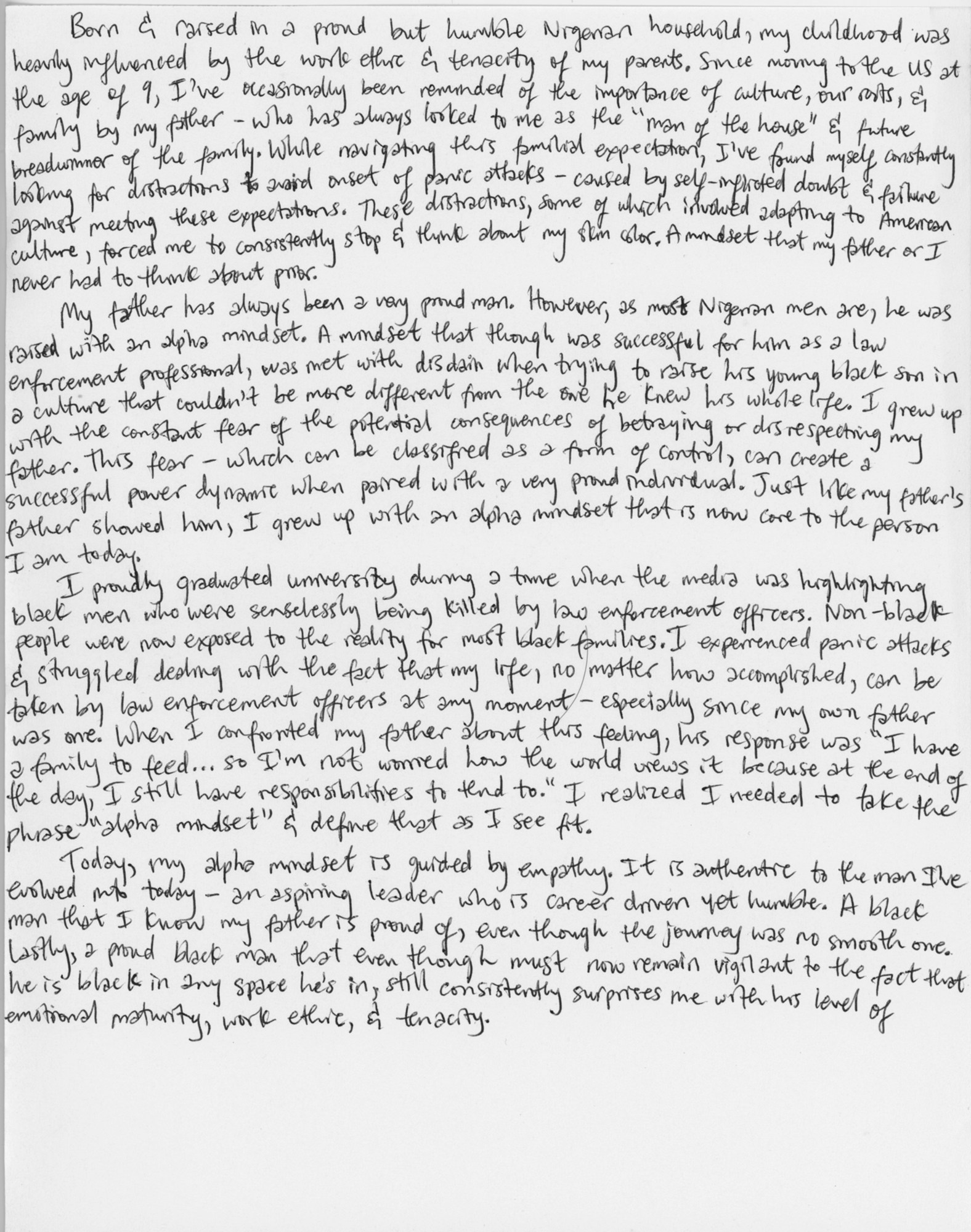

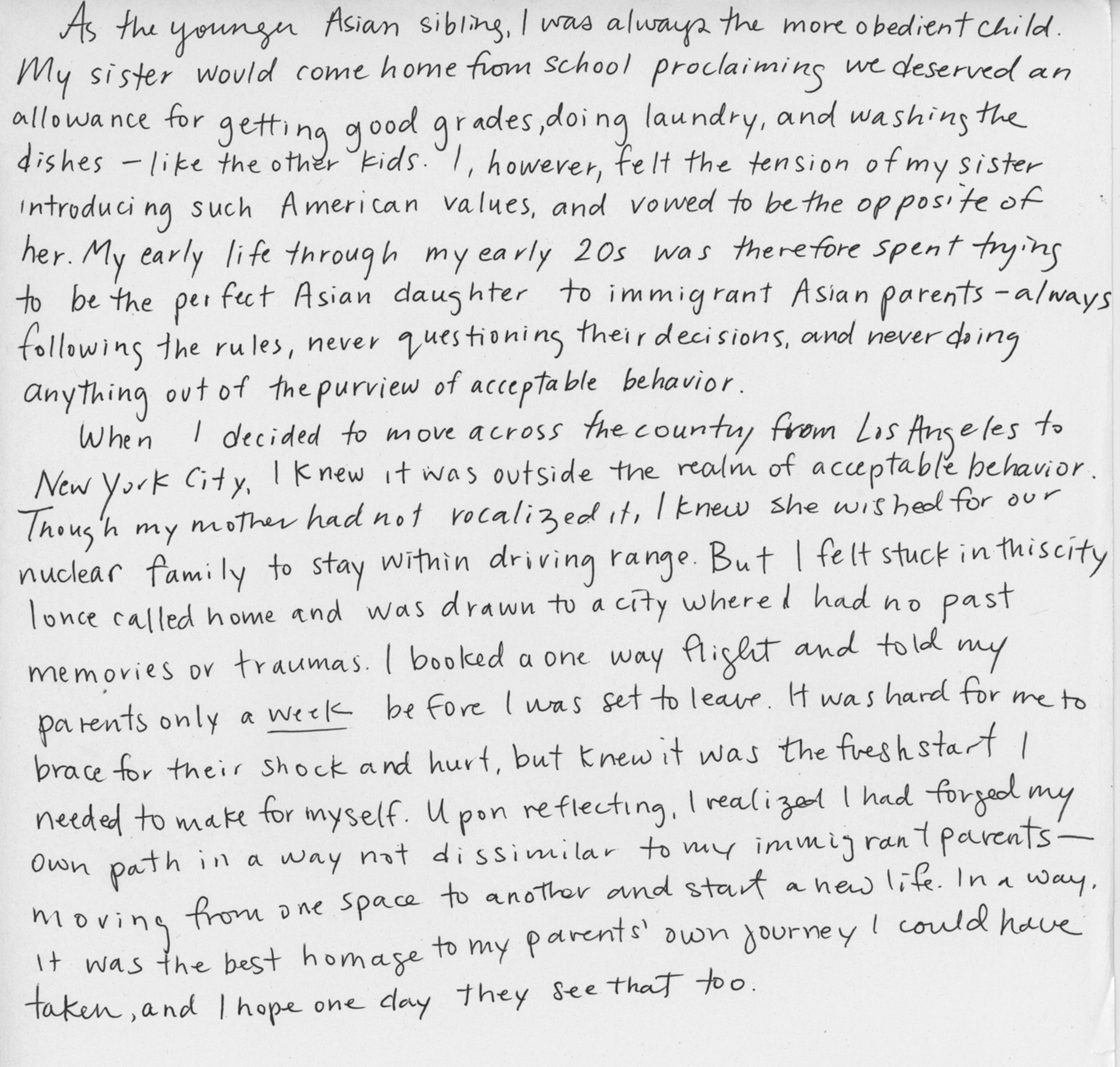

Four years in the making, Kyle’s project spotlights 30 parent-child relationships, all centred around the diasporic landing point of New York City. Structured in diptychs, he takes an archival image of an immigrant parent and shoots an interpretive recreation of that image with their child. Side by side, then and now, we see two generations waving in front of the Statue of Liberty, posing in Times Square or Chinatown, sitting in barbershops, sprawled out in city parks, or smiling beside fairground rides. The recreated images, shot by Kyle on film to evoke the nostalgic hue of the originals, are accompanied by the young person’s handwritten reflections on their relationship to their parent and their ancestral culture.

Among many things, Sowing Rice With Salt is an exercise in empathy. “By visually placing the child in the shoes of the past version of a parent, I wanted to devise a visual bridge where the child could empathetically imagine their parent’s past,” Kyle says. “Many of the participants wrote about feeling frustrated with their parents growing up. As we get older and learn more about our family history and what our parents had to go through to succeed in the US, I think we’re better able to empathise with them.”

Growing up in Manhattan as the child of immigrant parents from Hong Kong, Kyle felt isolated in his experience of coping with cultural loss and assimilation, and describes his childhood as a kind of “limbo”. As one of the few Asian-Americans at his private school on the Upper East Side, he remembers racist jibes and always being the kid with the “exotic” lunch box – how, at the age of five, a teacher snatched his tea egg out of his hand and threw it in the bin, thinking it was rotten. But on weekend trips to Chinatown, he was known as the kid with the poor Cantonese and felt a sense of shame at being unable to communicate fluidly with older family members. “Being between those two worlds, there was always a desire to fit in,” he says. “But knowing I wouldn’t be able to, I just wanted to be invisible and not take up too much space, so my differences wouldn’t be noticed.”

Among the myriad struggles faced by second-generation immigrants, his decision to focus on parental relationships evolved from his own connection with his father. “I picked that topic at that time in my life, in my final year of college, because I was doing a lot of work reconciling my upbringing with my father,” he says. Reading through all the handwritten letters in the project, which move through a multitude of emotions, spanning gratitude, guilt, grief, misunderstanding, aspiration, acceptance, and reconciliation, the theme of sacrifice resonates with Kyle the most.

“My father always talked about the sacrifices he had to make, and for a long time, I internalised those feelings of guilt and the pressure to succeed,” he says. “For a lot of folks, there’s this balance between wanting to show love for your parents by making their sacrifices seem ‘worthwhile’ and pursuing your own sense of happiness and creative freedom.”

These complexities are everywhere in the letters, emerging from the clash of cultural values and customs, from the space between hardship and privilege, and from communicative ruptures – not only in differences between native languages but also between love languages. Aaron writes of the late-night arithmetic drills his dad forced him to do as a child and learning to see them as his dad’s way of showing love: “He demands a life for me better than the one handed to him… I’ve come to realise that what’s left unsaid leaves room for intimacy. We may not talk, but he speaks to me through his actions.”

Lillian details the discord between her life of “countless violin lessons, the SAT prep, the elite high schools and later, elite universities” with the hardships her mother faced, having left her studies, friends and family in China for the US with “nothing but a bag of books and $80”. Isaiah explores his love for the Trinidadian Soca and Calypso music his mother shared with him, which formed “a bond that remains strong today”, while Kingsley, “born and raised in a proud but humble Nigerian household”, grapples with the “alpha mindset” of his father, a law enforcement officer, and having to navigate his father’s profession as a young Black man.

“What prevails through the writings is the possibility and resilience of love in these relationships, despite all the tensions caused by cultural and historical gaps of knowledge and understanding,” Kyle says. “What makes this project so meaningful is seeing the diversity of the stories and how there are all these shared themes. Despite the silences around these conversations, you find out that the most intimate is actually the most universal.”

Though timeless in its themes, Kyle’s project has come at a moment of increased representation for immigrant families and Asian-American identity in popular culture, from A24’s Oscar-winning Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022) to Netflix’s dark comedy series Beef (2023), about an explosive feud between Danny, a failing contractor who’s desperately trying to build a house so his parents can move back to the US from South Korea, and Amy, an unfulfilled entrepreneur who’s estranged from her Chinese-Vietnamese parents. “I think Steven Yeun’s character, Danny, speaks a lot to this project. He has this intense love for his parents, and he’s trying to pay back his feelings of gratitude and debt in a very rigid way,” Kyle says.

As he prepares to exhibit Sowing Rice With Salt at this year’s Photoville Festival in Brooklyn Bridge Park, Kyle considers how he wants the project to be received. “Sometimes the folks I show these stories to are not the children of immigrants, but the project still tugs at their heartstrings,” he finishes with. “I want it to speak primarily to the community that it’s about, but I find it really gratifying that it’s speaking to this broader human desire to connect with the people who raised you.”

‘Sowing Rice With Salt‘ will be exhibited at this year’s Photoville Festival in Brooklyn Bridge Park, New York, from 3-18 June 2023. To see more of Kyle Lui’s work, check out his website.

Credits

All images courtesy Kyle Lui