“Plague! We are in the middle of a fucking plague! Plague! 40 million infected people is a fucking plague. And nobody acts as if it is.” When Larry Kramer gave this speech in September 1991 — ten years after The New York Times reported the appearance of a strange form of ‘gay cancer’ — AIDS had killed 150,000 people in America alone. “And nobody knows what to do next.”

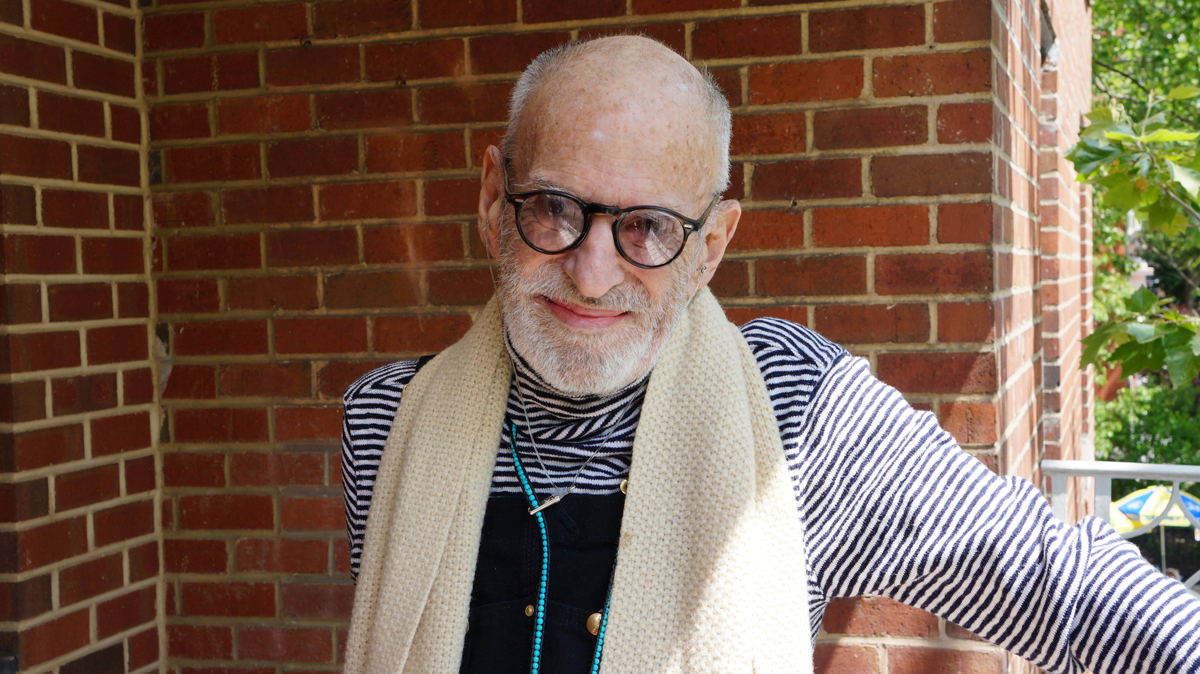

Larry Kramer is one of the foremost HIV and AIDS activists to ever lived. His acerbic tongue and valorous temper brought with it accusations of governmental plans to commit genocide on the gay population, and made him very unpopular both within parts of the gay community and without, but ultimately it brought results.

“I guess I was brought up to believe in right and wrong, and how gay people are treated is wrong and that makes me angry and that’s enough,” he retorts down the phone, in response to a question about what caused him to speak so loudly both throughout the AIDS crisis of the 80s, and today when that crisis rages on. “I believe gay people should have the same as everyone else and AIDS has showed us that that simply doesn’t exist. It’s the 35th year of a plague that would not have existed if it was not in the world’s mind that it was caused by gay men. I’m a fighter and I want everyone else to be a fighter.”

Larry Kramer in Love & Anger is the title of the HBO biopic about the writer-cum-activist’s life, which airs in London this weekend. At 80, Larry is one of the few people who has seen the political and social landscape for gay people change over decades — from our time in the Pines on Fire Island, to the outbreak and rise of HIV and AIDS through the 80s, into a people today who have been politically pacified with promise of equal marriage, and treatment but no cure. It is in part a look at Kramer as a person — the film debunks his incendiary reputation, and presents him as someone who cares so overwhelmingly about the treatment of gay people — as well as a chronological account of his work as a writer and activist who crystallised the fear and urgency of the rise of the ‘AIDS plague’ in a time when nobody was really listening, or writing, about it.

Initially resistant to the making of a movie about his life, friend Jean Carlomusto told Larry she would make it anyway, and so he consented. And what does Larry want people to take from the film? “I want gay people to know their history and what it was like during those early years, and I want them to see how you can get things accomplished through activism if there are enough of you fighting together in a united fashion for a specific goal.” Even still, Kramer is fighting for the gay population to be taken seriously, he wants to incite rage rather than assimilation, a fighting spirit in favour of passivity.

“Why do we have to fight now? Listen. You have to fight everyday of your life. Activism is a seven day a week job — to get what you deserve — and if you’re not fighting for it you can’t complain about not having it.” Kramer is at once proud, and very critical, of the gay community — which he has now dubbed the gay population, because “there are many communities of different sorts of gays.” Along with the documentary, he has channeled his confusion about the gay population’s apparent inability to fight into writing a book, to prove why this might be.

The American People is Kramer’s history of homosexuality in America: “gay people, even when there wasn’t a name for us — have been treated cruelly since the very beginning of America, and it continues until the present day.” An undeniable claim the world over in fact, and upon ending our conversation Kramer halts the niceties of the farewell, “if I wanted one thing, one gift, from everybody, it would be that they would go out and read about our history. The American People is an attempt to show everyone where we came from, and I think it’s important for every people to know their history, and we have an amazing history, so let’s educate ourselves.”

It’s true. As a community of gay people we are pacified. Perhaps now in the West the prognosis is slightly better than when we were being ignored — and as Kramer puts it, murdered, by bureaucracy — but the upshot is still a life of absolute otherness, of outsiderness and of not being taken seriously.

Kramer has fought for over half of his life so that there would be a gay community in existence to actually have a history, which he has now written. He is an integral voice in our heritage as gay people and, along with so many, we have Kramer to thank for our continuance.

“Well, why is it any different today than when the first case [of HIV] was announced in 1981?” Kramer pushes. In truth the fight is far from over — 39 million people have died from AIDS related illnesses since that NYT article back in 1981. So what to do next? Perhaps brushing up on your gay history is the best place to start.

Credits

Text Tom Rasmussen