The courtyard at the Royal Academy has been transformed with gold-rimmed fountains, towering palm trees and a giant, personalised Jeff Koons silver bunny. But it’s not actually the British art institution’s Piccadilly home, rather it’s a scene from Unreal Estate (2015), a video game engine-generated simulation created by Lawrence Lek, in which the grand Palladian mansion has been converted to an oligarch playboy’s fantasy on a private tropical island. “I’m really interested in the experience of a place, which isn’t necessarily dependent on physically being somewhere,” explains the London-based Malaysian-Chinese visual artist. “That could be through film or literature, as much as architecture,” the field in which he studied at the University of Cambridge and New York’s Cooper Union. “I’ve been making these virtual worlds for about six years now, and that came about because of the freedom that virtual reality provides. It allows you to explore the intersection between real and imagined worlds, which is what you see in the installations, films, music and video games that I make.”

![Lawrence Lek, Unreal Estate (the Royal Academy is Yours), 2015 [still]. © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.](https://i-d.co/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/1585051104880-LawrenceLek_UnrealEstate_02_high_quality.jpeg?quality=90&w=2000)

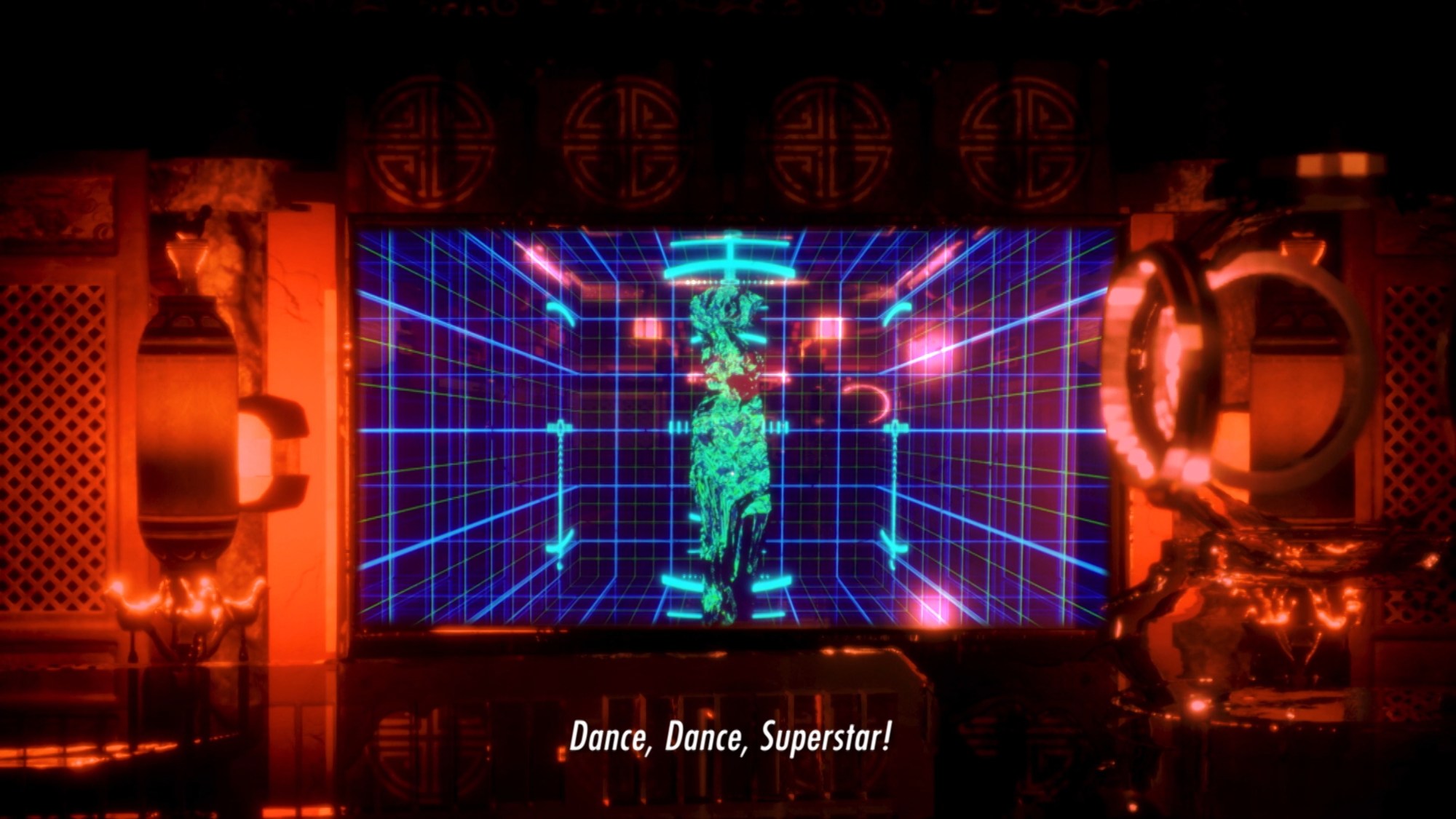

It’s in Lawrence’s most recent installation, Temple OST (2019), exhibited as part of TRANSFORMER: A Rebirth Of Wonder at 180 Strand, that all of these elements most seamlessly converge. Visitors entering the building’s cavernous concrete basement were welcomed into a slick, neon-lit nightclub, with overhanging screens playing simulations of a walk from Temple tube station to the unreal nightclub in which the viewer stands, all soundtracked by the artist’s own music.

His feature-length works achieve a similarly uncanny effect, albeit through narrative complexity rather than through the overlay of simulation and reality. Geomancer (2017) tells the story of its titular protagonist, an AI satellite with dreams of becoming an artist; AIDOL (2019) follows the quest of faded star Diva for enduring fame with now-ghostwriter Geomancer’s help. Throughout his work, there’s a pervading sense of how mutable ‘authentic’ human experience is — as well as of how porous the boundary is between it and ‘artificial’ intelligence. We chatted with Lawrence about his approach to creating his uncanny virtual worlds, humanised AIs, and how music drives his process.

![Lawrence Lek, Temple OST, 2019 [still]. © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.](https://i-d.co/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/1585051497364-02_LL_TempleOST_vlcsnap-2019-10-20-23h22m33s210_high_quality.jpeg?quality=90&w=2000)

With your site-specific works, there’s an interesting relationship between being physically present in a building and seeing it replicated and abstracted on a screen. What’s behind your approach here?

With both site-specific installation and sculpture, there’s this idea that you should relate directly to the site. In my earlier work, I was thinking about how that might translate to the virtual world. With Unreal Estate, which is based on the Royal Academy (RA), there’s an aspect of political commentary about alienation and xenophobia as the same thing. Since I’ve been in London, there’s been an increasing prevalence of this narrative of oligarchs buying up the country. Whether they’re Middle Eastern, Russian or Chinese, it’s the same projection of the other. But there’s also a sense of envy that operates there as well, this sense of ‘If I can’t be in that position, I’m going to take it down.’ With the RA specifically, Burlington House used to be a private mansion, so I thought it would be funny to return it to its original state, exaggerating that premise in a way. For example, in the middle of the courtyard, there’s a statue of Joshua Reynolds, the RA’s first president, holding a paintbrush and pointing into the distance. Translating that to ‘Unreal Estate,’ I thought that a billionaire might commission Jeff Koons to make a bunny in the same pose.

How does that approach play out in something like Dalston, Mon Amour ?

Well, it’s a completely different context. It’s set on Gillett Square where there are always skateboarders and old rastas hanging out. It’s a public space, but then there’s the sense that it’s always under the threat of regeneration or loss. As a sort of analogy to that, I set it within this post-apocalyptic landscape, centred around the Rio Cinema. In it, Hiroshima mon amour by Alain Resnais and Marguerite Duras, plays — which is about loss, the trauma of war and the way that changes your memory. It’s a cliche, but every time I go to Dalston or Shoreditch, I’m always struck by how much it’s changed, and you start questioning your personal memories of a space in light of what it is now.

![Lawrence Lek, AIDOL, 2019 [still]. © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.](https://i-d.co/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/1585051302884-AIDOL-Screenshot_03_LL_4k_high_quality.jpeg?quality=90&w=2000)

You often use tropical scenery — sand and palm trees in Dalston, for example. What role does climate play?

There’s definitely a Ballardian, The Drowned World vibe, a sense that the entire world has changed. I wouldn’t say that I make ecological work, instead, I use atmosphere in what is essentially a set design to situate it, to take familiar landscapes and then other them somehow. I often use weather to evoke a mood that may not be completely conscious or understood, which is a widely-used literary device. With physical filmmaking, you’re dependent on the weather, but because I work with simulation, it’s something that I can be in control of.

The digital reproduction of physical landmarks raises interesting questions about copying and originality, too

When I was studying architecture, the objective was to make an iconic building — like Thomas Heatherwick, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas — whose form has never been seen before. I was essentially trained with this idea of innovation as a consequence of formal originality. But at the same time, I’m a big fan of pop culture. I like basic stuff, basically. The most logical entry point for me is just doing something that I would personally want. I would love to live in the RA, for example, or I would love to make this dark basement at 180 Strand into a nightclub I would want to go to. Whereas copying and originality is more kind of a formal concern, when I’m working with film or music or virtual worlds, it’s more of a collage-based reality — I’m free to draw from many different things. It differs from, say, appropriation art, where the artist wants you to know that they have either stolen or borrowed or doctored something that already exists. Because I’m always remodelling things, it’s also an act of reconfiguration.

Music plays a central role — in AIDOL especially, it seems to carry the plot along. How does music affect the visual direction you take?

With Geomancer and AIDOL, the process was pretty chaotic. I would write some of the script, and then do work on some music to set the emotional tone. CGI on its own is, fundamentally, a medium about nothing, so it’s really important to try and ground in some kind of emotional expression to start with and then allow that to pervade things. But I wouldn’t say that one part’s more important than the other. Sometimes the soundtrack comes first, and then the film, other times it’s the other way.

![Lawrence Lek, Geomancer, 2017 [still]. © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.](https://i-d.co/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/1585051363018-Geomancer_03_1920x1080_high_quality.jpeg?quality=90&w=2000)

In your work, AI is often discussed in terms of genealogy and ancestry. Would you say that you try to bridge human and artificial intelligence?

For me, humanising or personifying AI isn’t intentional. That said, the more I’ve explored, and questioned my own reactions and motivations, the more I’ve started thinking: ‘Is my own creative process not algorithmic?’ I want to make a film, and build this world within it. And I have my own criteria as for what makes for a successful artwork, and to achieve that I make dozens and dozens of choices every day based on my own personal human value judgment. That’s essentially an algorithmic process, too. As much as I’m personifying an AI by giving it genealogy, history, emotions or a voice, I also notice myself becoming even more aware of my own biases, processes, and the patterns that I fall into.

The use of different languages seems to be tied to similar notions of bias — you seem to play with the power associated with them.

The geopolitical implications of each language are very important. I want to make it ambiguous what region the film is for, but also, each language has particular cultural connotations. For example, Geomancer speaks Mandarin, the most generic Chinese, which an AI would speak in order to be universally understood, but the AI dealer in the casino speaks Cantonese. Choices like that have subtle but pervasive implications — in communist China, they made Mandarin the standardised language and they actively tried to decrease the amount of people using their own dialect, moving people from one region to the other so they couldn’t actually create these localised, provincial forms of solidarity. In Singapore and Hong Kong, on the other hand, being diasporic countries, dialects are much better spoken than Mandarin Chinese especially among older generations. That obviously doesn’t necessarily communicate to everyone, but in cases where people do understand, like if it’s shown in Hong Kong, people will get that.

On an experiential level, though, I really like playing with the sound of the language. For example, if you had two human actors read the script of AIDOL, the dialogue would flow quite naturally. I, on the other hand, generally like to cut the phrases and add more space in between them, so that the subtitles, whether in English or Chinese, are something to be read in their own right. Very often, subtitles are the ultimate afterthought, but when I was writing the script for Geomancer, I was conscious of the fact that how text appears on the screen is a significant part of the image. I therefore wrote in aphorisms, rather than natural speech — sentences that would look good on screen.

![Lawrence Lek, Geomancer, 2017 [still]. © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.](https://i-d.co/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/1585051561364-Geomancer_05_1920x1080_high_quality.jpeg?quality=90&w=2000)

You mention the casino dealer in Geomancer — given how driven they are by programmed logic, isn’t it odd that an AI would want to gamble?

In Geomancer, I was thinking that the ultimate fantasy for a superintelligent AI would be to participate in something where chaos, or pure chance, reigns, something incalculable. But the reason I chose a roulette wheel specifically is the fact that people can still place bets when both the wheel and ball are still spinning. I thought that, in theory, if you had sharp enough resolution and a superfast frame rate, you could calculate where the ball would end up. While that would be very, very difficult, does it still count as chance?

But it wasn’t just about this idea of chance; it also comes down to this very deep cultural belief in fate — an equivalent distinction in Western philosophy can be found in the conversation around free will. In Confucianism, there’s a sense that you’re born into a preordained position — emperor or farmer or anything in between. It’s possible to rise above that, but there’s a real ‘don’t make too much of a fuss’ sort of vibe. Within that, I think it becomes clear why gambling is so culturally significant. Money embodies fortune on a philosophical level, but also on a practical level — it means the ability to provide for your probably very large family. The importance of gambling, to me, isn’t just that it operates through chance — it’s that it offers a potential shortcut to success outside of the system.

The soundtrack to Temple OST is now available via The Vinyl Factory

![Lawrence Lek, AIDOL, 2019 [still]. © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.](https://i-d.co/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/1585051640742-AIDOL-Screenshot_01_LL_4k_high_quality.jpeg?quality=90&w=2000)

![Lawrence Lek, AIDOL, 2019 [still]. © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.](https://i-d.co/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/1585051858434-AIDOL-Screenshot_06_LL_4k_high_quality.jpeg?quality=90&w=2000)

![Lawrence Lek, Temple OST, 2019 [still]. © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.](https://i-d.co/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/1585051929480-12_LL_TempleOST_vlcsnap-2019-10-20-23h31m30s128_high_quality.jpeg?quality=90&w=2000)