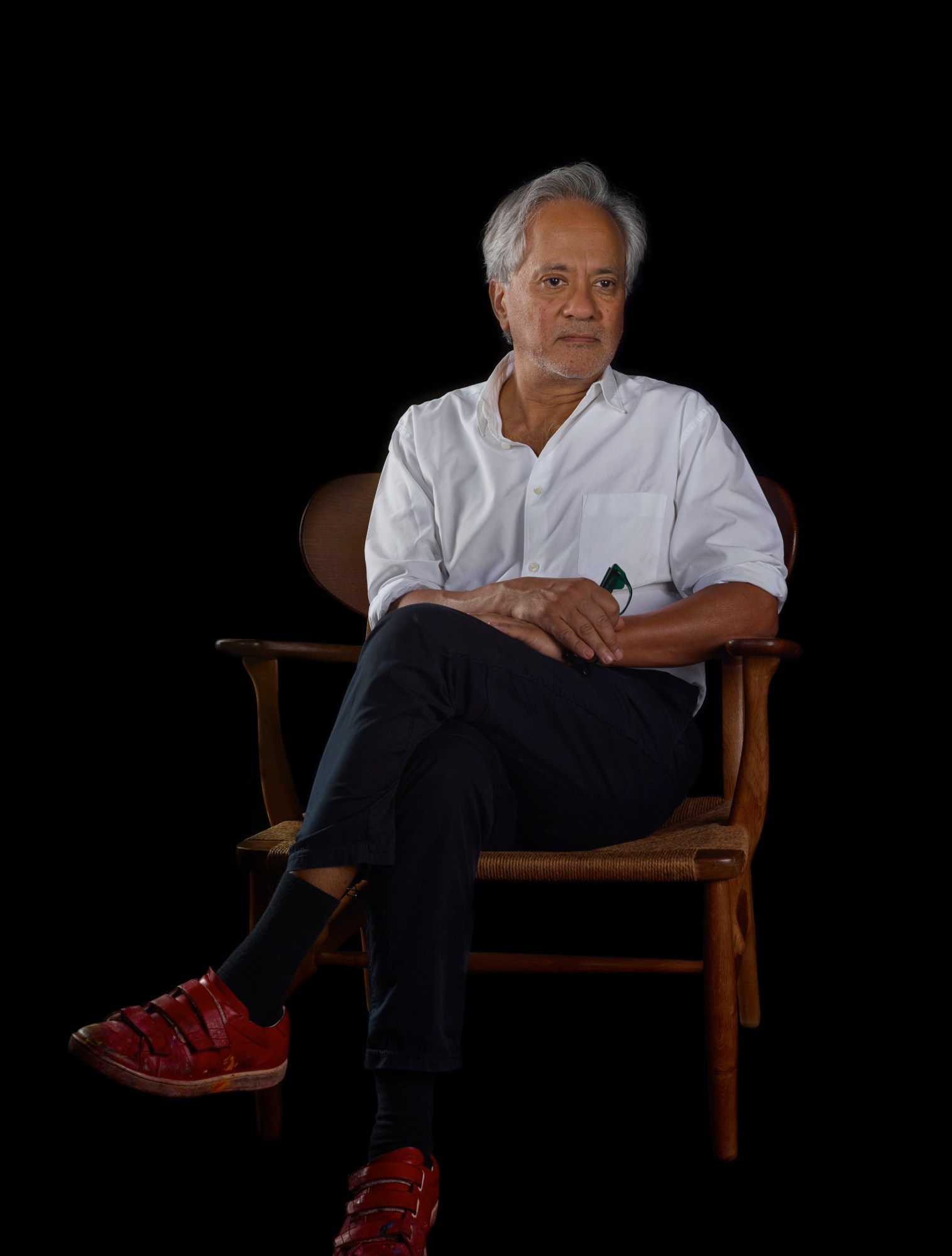

Catherine Opie’s most famous portrait is called Pervert, and it features the photographer in a gimp mask, needles piercing her arms, she’s topless and has the word pervert scratched into her bare chest. Her most recent body of work, on display at the moment at Thomas Dane Gallery in London, features stately and regal portraits of grand dames and icons of the British art world. No gimp masks, just Anish Kapoor and David Hockney and Gillian Wearing. The portraits recall the stark beauty of the Baroque-era, with sitters upon deep black backgrounds, Catherine’s body of work plays upon the interweaved history of painting and photography, and changing ideas of what it means to document and represent the world we live in. We caught up with the artist for a chat.

Do you still get nervous about showing new work to the public?

No, not really. I still get excited though. I’m happy with the portraits and I’m excited because I feel good about the work. The only real nerve-wracking moment was when I was included in the 95 Whitney Biennial, which was the first time people ever saw those self-portraits, Pervert especially.

You’re a very American photographer and a lot of your subjects are very American subjects.

My work is about identity and being an American, that’s what I look at, the specificity of American identity. I’ve been mapping that out for however many years now.

This is very different though. What drew you to Britain and made you want to make portraits of famous British artists?

They’re primarily British artists but it’s not a series just about that. My niece is in it, for example, with her young son on her lap, and that’s a bit more allegorical rather than a straight portrait. I’ve been coming to London since the 90s, and I just wanted to do something with all these amazing artists, many of whom I have a long friendship and relationship with. So it comes out of mutual respect.

Some images feature people very well-known for their portraits and self-portraits too.

Yeah, Gillian Wearing, for example, or Celia Paul, David Hockney, too, is a great portraitist. I wanted to make a portrait of someone who works in self-portraiture, like Gillian, who’s often behind a mask in her self-portraits. I wanted to think about what it means to make a portrait of someone who is already thinking about portraiture. I loved the conversation that came out of that.

Did you notice a difference between shooting Gillian, who as you say, works a lot in self-portraiture, to say Anish Kapoor, whose work is very non-representational.

I enter the photography studio thinking about the artist’s works, sure, but I try to interrupt the idea a little. So, for example, in Anish’s portrait, his foot is out the frame. And for me, that’s a nod to Hockney and the way he frames portraits. Anish is a really formal artist, and I wanted to draw the focus onto something a little off, but I also wanted to make it a conversation between the different artists in the series.

So does a lot of the work come before the sitting?

Yeah, but the portrait only emerges during the sitting. I tell them they’re sitting for a formal portrait, and that’s about all the information I give. There’s a conversation in these portraits with the Baroque, and with painting, and then when people come to the studio things emerge from that framework. I move their body around and I’m fairly controlling. I don’t necessarily have a preconceived idea of what the final portrait will look like exactly. It’s a dance, really, but I work very quickly in the studio.

Really?

Oh yeah, but they don’t look it, do they? They look like they take a very long time. But it goes very fast.

I think it’s a trick of the mind with the references to that very Baroque style of portraiture.

When you look at those old paintings, they were sitting there for a really long time, and they have that pensive, bored, stare — so I try to get people to not engage with the camera. I want them looking off, out of the shot, but I want the viewer to spend a lot of time with the work. I like the idea of engaging with looking at somebody. It feels very intimate without having an intimate moment. Sometimes you need a portrait to gaze back, but if every single one does it loses its power — you need a bit of shyness to create a space for viewing. I really want these portraits to hold you, to not be something to flick through quickly on our phones.

What drew you to this style of portraiture?

I’ve always been interested in painting. The early portraits I was making in the 90s of my friends in the lesbian scene, well that was referring to Holbein, and how he developed portraiture in his era. The invention of photography really changed portraiture, because it changed our ideas about the nature of representation. Painting at one point was about documentation, whether it was a person or a period in time or the artistic influence that was around. I hope how I construct these pictures holds that way of wanting to engage with those ideas.

You teach at UCLA right?

Yeah, why do I sound like a professor now?

No! I was just wondering, well photography changed portraiture, but the people you teach, has their relationship to photography changed because of the access, ease and shareability of image-making now? To make a portrait of your friends, or to create a self portrait, well that’s the easiest thing in the world to do and distribute.

I did a class about four years ago that was called Selfies, Self Portraiture #whatthefuck. And I really had them unpack all this. With this series, I want to challenge that relationship between portraiture, paintings and photography. This isn’t documentary photography, it’s not photography for Instagram, it’s very formal, it’s very slow, it’s about looking at something and taking in it. I want people to really see the work, be emotional with it, and allow a subtlety and allegory into the work of photography too. There’s a lot of questions I want the work to ask.

I was reading an old interview with you, where you said you wanted to avoid using squares in your photography because there was too much association with Robert Mapplethorpe, but now the square is associated with Instagram. It’s totally changed what it means to use a square photograph.

And originally for Instagram the square mimicked the Hasselblad camera, or a Rolleiflex, or a 120 roll of film. I was watching the iPhone 10 demonstration, and there was an option on the camera to do a portrait with a black background. I was like ‘Huh! That’s fucked up.’ I was working really hard at getting that effect right.

And there is also the new abstract landscape work in the exhibition.

The White Cliffs of Dover.

Ah that’s what it was.

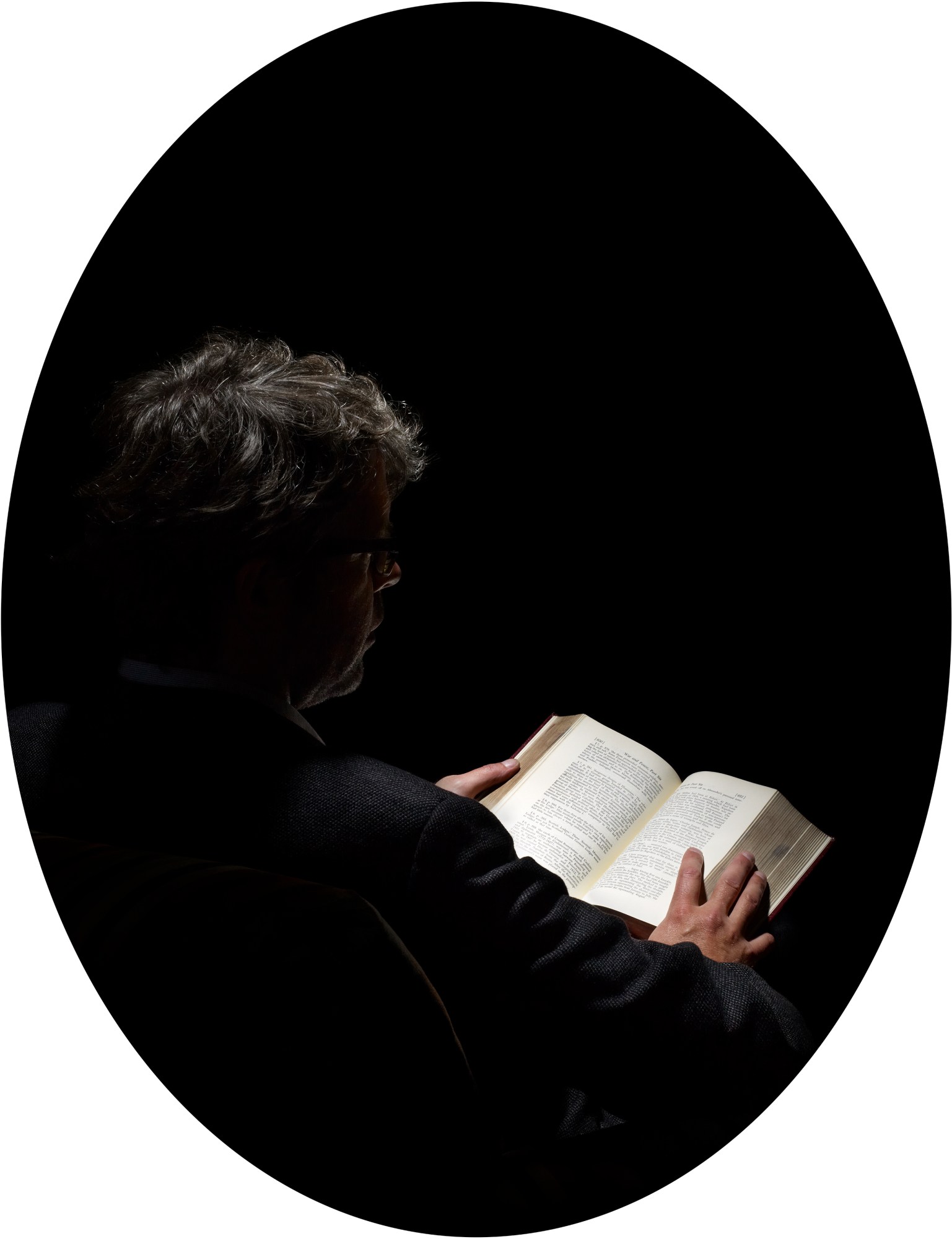

Oh fuck I wasn’t supposed to tell you, it’s Untitled. It’s meant to be like, you think you know, but you question whether you know, and that is completely linked to… well a smear of the abstract changes everything. I happen to have a house in the Sequoia National Forest, in California, which has some of the biggest and oldest trees in the world. Every day you see people get out, they stand in front of the trees and they take their pictures on their cell phones to prove they were there, and post them online immediately. What do these landscapes mean? I’m really interested in that. The first time I ever saw England I came in from Holland on the ferry, and they [the White Cliffs of Dover] were the first thing I saw. In the UK you have an amazing landscape, but it’s not necessarily iconic. It’s about greenness, springtime, sheep. Although the sea is a part of the landscape too. This was my way of bringing that in, I wanted it to hold you, to create a question, in the way the portraits hold you, I want people to think about it in the same way that they might think about the portrait of Jonathan Franzen reading War and Peace.

All photography © Catherine Opie, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Thomas Dane Gallery, London