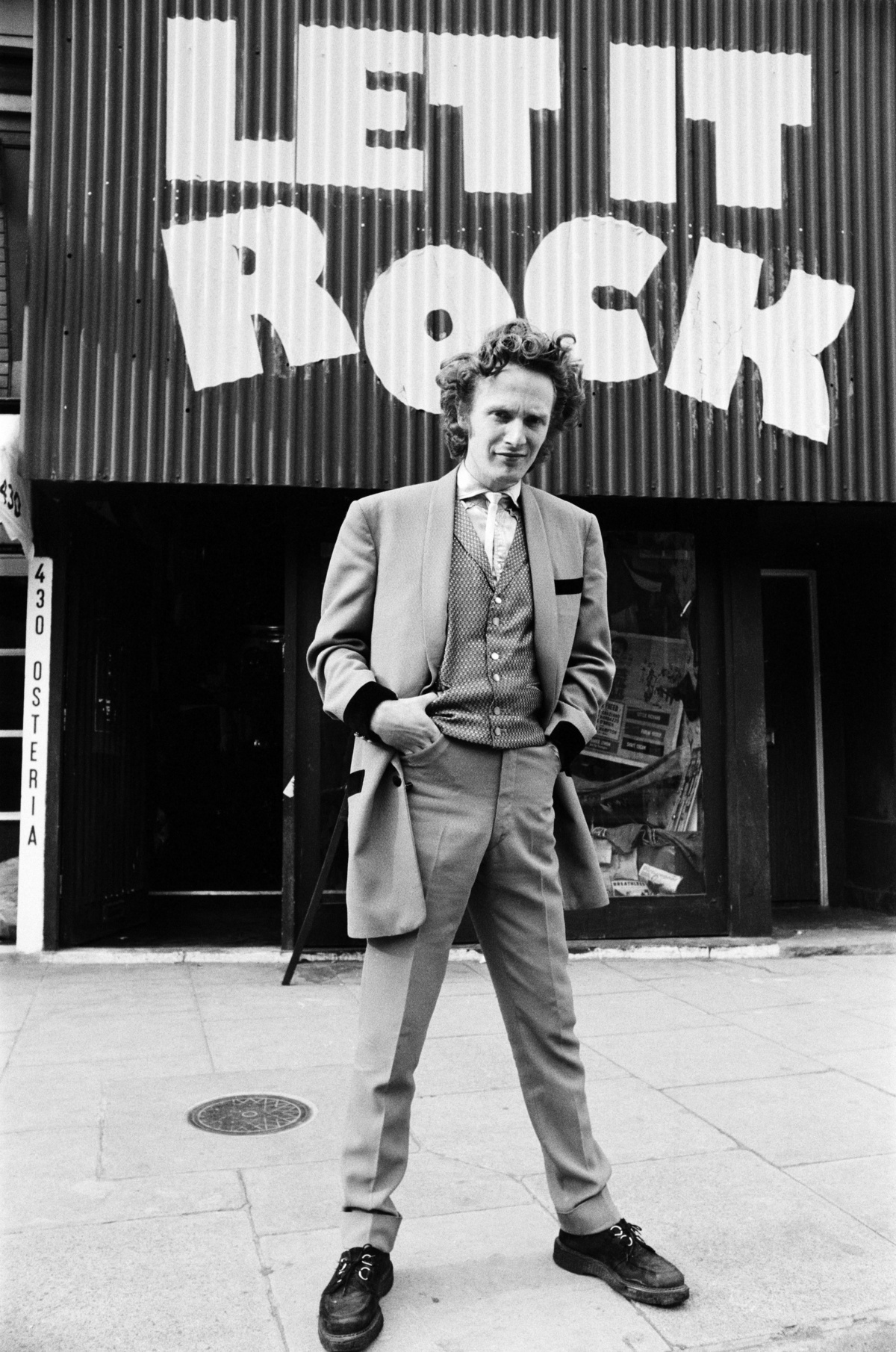

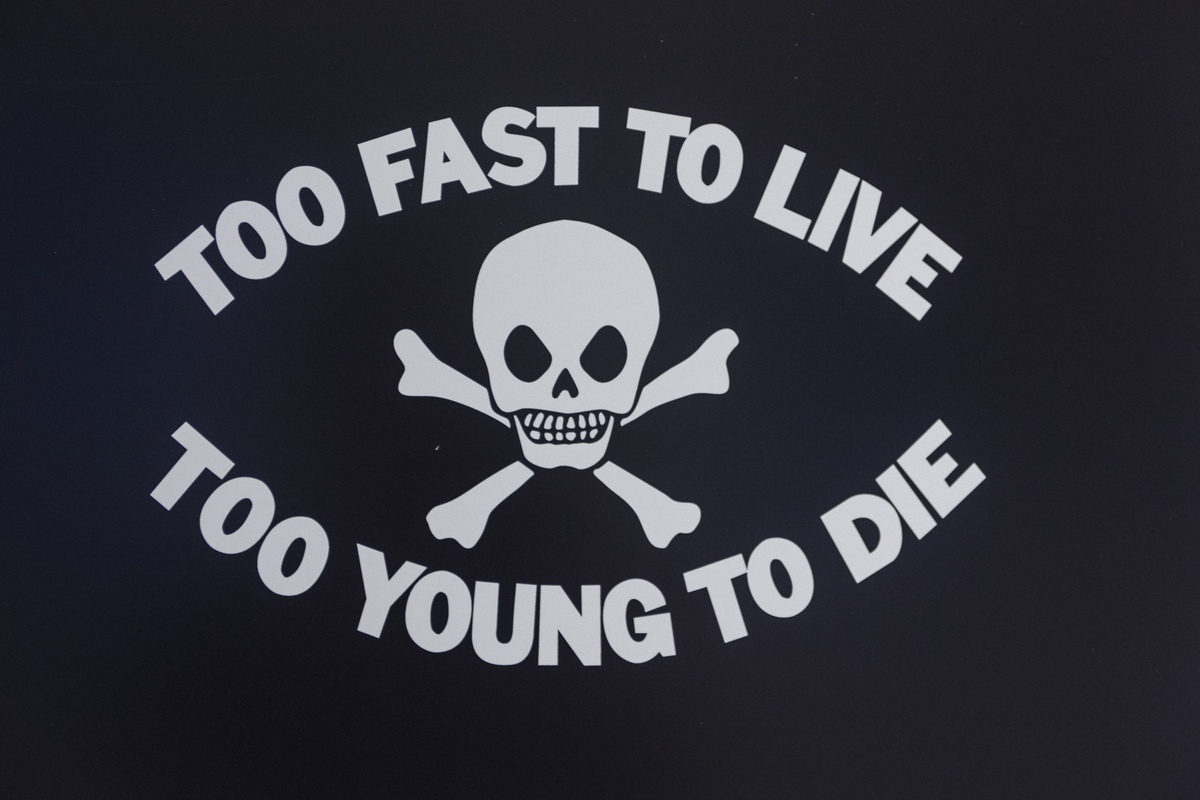

Alongside showings of rare films, the Young Kim and Paul Gorman curated Let It Rock: The Look Of Music The Sound Of Fashion is an ephemera-filled environment that revolves around installations dedicated to the shop from which it takes its title. Divided into six sections, each area is dedicated to the manifestations of 430 King’s Road as well as Nostalgia Of Mud, the space operated by Malcolm and Vivienne Westwood at 5 St Christopher’s Place in London’s West End from 1982 to 1984.

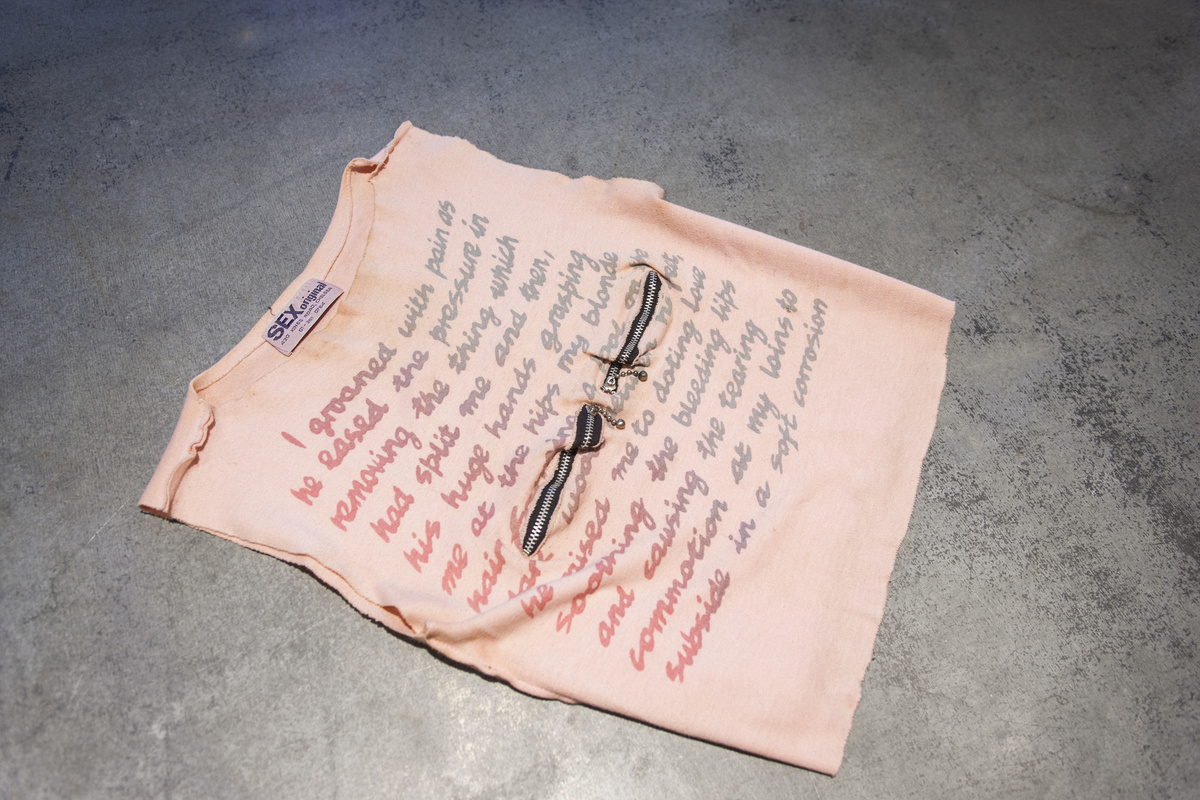

Clothing, documentation, notebooks, flyers, invitations, posters and films can be pored over. Each piece is loaded with narrative. A single tie made by re-appropriating vintage cloth, now holds the story of how it was made and the moment it captured, the people who wore it and the people who own it now. The colourful chaos and powerful provocation has lost none of its impact. You can lose yourself in these masterfully mapped memories and echoed experiences. So much has been remembered and so much already seen but not from this position. Young and Paul have curated an emotive experience that enables the visitor to view this familiar world through fresh eyes, through Malcolm McLaren’s eyes.

What was the catalyst for the exhibition?

Young: I want people to understand everything from Malcolm’s point of view. To understand what he created and why because that’s important to know. Everything came from the mind of an artist, there was a reason for it, it was entrenched in pop culture and in terms of the clothes themselves, he had real knowledge. He was someone who knew what they were doing. Everything is so beautifully made.

How long have you been planning this exhibition, both mentally and physically?

Young: Well… (laughs)… through a Japanese journalist, we were approached by Arnauld Vanraet, one of the the creative directors of The Crystal Hall, in May and due to Danish holidays, we had to turn everything around in June.

That’s remarkable, I thought you were going to say months, years even. The exhibition is so articulated, both in its conception and curation. It feels as though it should have already happened.

Paul: There’s reasons for that but now just feels right, everything in its time.

Young: We’ve been working on compiling everything as we’re planning a book on the clothes specifically, so we have been gathering and organising for the last year and a half. If that preparatory work hadn’t been done, it would have been impossible.

Paul: The moment we were approached, we knew precisely what we wanted to do and what we didn’t. We didn’t want to get hung up on Punk.

Young: Everyone thinks they know punk, few really do but as this is a fashion fair, we wanted to focus on the clothes. It was a period of great creation from Malcolm and not many people realise that anymore. For some people, as Vivienne continued in fashion they dismiss Malcolm’s design role.

Paul: They think he was a shop manager.

Young: He came from a fashion background, his grandfather was a Savile Row tailor and his mother had a dress factory, he grew up around clothes. He really knew and understood how clothes were made.

Paul: He was hugely knowledgeable of cut and construction. He had this background, went off to art school at sixteen and engaged himself in an art education, had his first exhibition in 1967 when he was twenty one and when he left, he had this overriding interest in music. It was always about music for Malcolm and from that an interest in fashion, fusing this together led to Let It Rock.

How would describe Malcolm’s creative approach?

Young: He was an artist who constantly had ideas. He wanted to express himself freely. He fell into fashion in a sense because he needed to survive, to make a living after Vivienne fell pregnant. He initially stole books from the library and sold them. He was trying to find his way and ended up going to flea markets and buying surplus military material, found this store on the King’s Road and went from there. He was an artist making commercial fashion and that’s why the stores were treated as installations, they didn’t last long because it was all about creating new ideas.

Paul: He was the editor, the art director and creative director in one. He conceived garments and was involved right through to the end. His process that goes back to Let It Rock…

Young: … is collaging and combining different influences together to create something new.

Paul: It’s Postmodern. Today, we can place him as an artist within the narrative. There’s certain principles that define Postmodernism and Malcolm ticks all of them. It was revolutionary at the time.

He was a great collaborator too, how would describe his approach to collaboration? Did he seek emerging talents or did were they drawn to him?

Young: It was both, he was great at getting the best out of people.

Paul: There was such a gravity around him, people wanted to work with him and Malcolm was always open to talk to any student. They found like-minded people in London but did the same on visits to New York too. It was a great time of idea exchange and held on to this throughout his life.

Young: He was drawn to new things and he loved young people.

Would he have considered himself a fashion designer at the time?

Paul: At that time, I think so. A bit later on he said he had been a fashion designer but ultimately, he was an artist.

Young: He certainly didn’t want to be part of the fashion establishment. He used to chase people from Vogue out of the shop.

Paul: There’s a great early interview where he said, ‘I hate chic!’ It didn’t take long before it received great press, there’s a double page spread in The Sunday Times Magazine, four months after it opened. People like Valerie Wade who wrote that piece and now has an antiques shop on Fulham Road, Janet Street Porter and a few others had access but it was very much an underground thing, it was a tiny shop of mainly one-off items.

It was an ever evolving subculture.

Paul: It was. There’s another great quote from Malcolm where he said, ‘kids today are waiting for something to happen.’ He brought it through. It didn’t happen by accident.

Young: Malcolm knew how to connect with youth, he fused pop culture in a way that was truly exciting.

How much of it was anticipating a moment that was yet to happen or observing something that was already beginning?

Paul: You have to remember that he was involved in the political revolts of the late 60s, that was shifting the intelligence of the time and he knew the mechanisms of shaking things up.

Young: All of the ideas you see here were part of Malcolm for such a long time. At the time, I don’t think he himself anticipated what it would all mean, the impact it would have.

Did he keep an archive?

Young: He held onto very little and anything that was kept was disorganised. Thankfully, the people he worked with did. He worked with hoarders, photographer Bob Gruen kept everything.

Paul: Malcolm was an artist, once an idea had been realised, he moved on.

As you worked through the archive and walk through the space now, was there anything that particularly surprised you or left you most excited?

Young: A printed wool dress from the Nostalgia of Mud collection of 82/83. The print itself came from a record he found during his research for Bow Wow Wow and world music.

Paul: The silhouette is powerful as it is but it’s all about the layers of influences and materials.

Young: The Witches outfit with the Keith Haring collaborative print, generously loaned by Kim Jones, is so fun, it could be worn today.

Alongside the Off-White exhibition, do you see a certain synergy between Malcolm’s body of work and Virgil’s?

Young: They’re both street fashion. Malcolm created expensive street fashion, it wasn’t couture like the French were doing it but it was still beautifully made. In this sense, you can see similarities with Virgil.

What’s next for the exhibition?

Young: There’s been so much interest in doing something but it’s all about doing the right project. I’m very happy that this was able to come together in such a tight deadline. By chance, this exhibiton, in some form atleast will travel to a music and fashion show in Grenoble in October and then we’ll see.

Credits

Text Steve Salter

Photography Jean-Francois Carly