Across his six novels, Alan Hollinghust has become one of the foremost literary inquisitors of the LGBTQ experience in modern Britain. His debut novel, 1988’s explicit The Swimming Pool Library, was described by The Guardian as “the first major novel in Britain to put gay life in its modern place and context”, while 2004’s Man Booker Prize winning The Line of Beauty explored themes of repression, hypocrisy and the AIDs crisis. His 2011 novel The Stranger’s Child adopted a more indirect approach to this investigation, instead focusing on the question of the sexual mystery of the past. “I’ve always been very interested in it, and I seem to keep going back to writing about earlier periods when it was much more difficult and complicated being queer than it is now,” he explains, “but also showing that life went on. It may not have been quite so conspicuous or uninhibited, but it did go on.”

His latest novel, the exquisite and expansive The Sparsholt Affair, accumulates all these themes in a narrative that traverses 70 years. The book hinges on a scandal that takes place in 1966, a year before the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality, which alludes to some sexual impropriety that results in the imprisonment of the enigmatic and handsome character named David Sparsholt. The novel, however, skirts the details of this “scandal”, instead spending its time focused on a cohort of academics at Oxford in the 1940s who come across Sparsholt as a teenager, and then later in the 1970s up to the present day as we follow his son, Johnny, a gay man and portraitist.

Yet, The Sparsholt Affair isn’t just a book that delves into the lives of queer people; it also explores the extraordinary impact of things left unsaid and what happens to relationships and reputations when things are just whispers behind closed doors. In this way, it mirrors queer literary tradition where often it’s what’s omitted that is just as important as what’s not — or as Hollinghust puts it: “The queer novelist had to, at a certain time, take on the prevailing conditions of the novel but do their own slightly subversive thing with it.”

With this in mind, we asked the Alan Hollinghurst about five of the queer books and authors that he himself views as important, and what they mean to him as a gay man and as a writer.

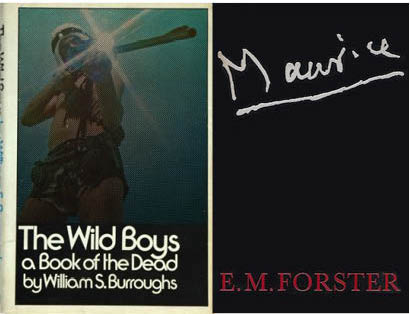

1. William Burroughs — The Wild Boys

“I remember reading Burroughs’s The Wild Boys when I was in the sixth form. A lot of it went completely over my head — I didn’t understand this world of junkies, hallucinations, or indeed what half the words meant. In a way, that added a further frisson to it. But all these extraordinary sexualised rituals being performed by these gangs was very exciting and glamorous to a boy from the English country boarding school. It’s interesting, too, that he’s not just a gay writer and that’s not actually his interest; it’s an element in his large, large imaginative activity. He’s very clever and very literary. He wasn’t just a fucked-up mess, although his life became so incredibly strange.”

2. E.M. Forster — Maurice

“I went up to Oxford in 1972 and I didn’t come out until my third year. I cannot honestly remember homosexuality being much talked about. Did we talk about Forster in that way? It’s so hard to think oneself back into the mind-set of an earlier period. Nothing had been published in his life time to acknowledge that he was gay. But then the year after his death, Maurice was published and then the gay short stories. Now, it’s so axiomatic to think of Forster as a gay writer, but up to that point certainly no one had written their undergraduate essay about it, so it was a huge change. When I started doing graduate work, which was in 1975 and so eight years after the partial decriminalisation, I chose to explore this subject as nobody really had up to that point.

“Of course, Maurice would have to be one of those books because it has an urgency of someone dealing with this very, very pressing subject. And since it has been published, it’s given us a taste of what it was like then. There are certain phrases, like when Maurice says to the doctor, ‘I’m an unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort’ that have entered into the way we imagine people understood themselves. It’s interesting, too, because of its underground life. Forster went back to it on at least two occasions, but the manuscript was passed around to people like Christopher Isherwood. It became like a sort of secret lifeline between gay generations, and I think that’s rather touching.”

3. Ronald Firbank

“Firbank was outrageous and his books were difficult modernist novels, coming out during the Great War (although the war itself never alluded to in any way). He had to pay for their publication himself — I think the earlier novels appeared in editions of around 300 copies. They developed a small cult, and I think he was a very significant influence and someone who completely shook up the novel as a form for the next generation of people like Evelyn Waugh, Henry Green and Auden, who was a passionate Firbankian. He showed what could be done by jettisoning the whole circumstance of the Victorian novel and building up these structures of glittering fragments through which you glimpse these shocking things going on. They’re very beautiful and very funny, but very elliptical; Firbank left a huge amount out, so it’s an art of condensation and simultaneous aeration.”

4. Denton Welch

“Denton Welch is a fascinating figure. Burroughs revered him and rather eccentrically dedicates The Place of Dead Roads to him. He even appears in a typically phantasmagorical way in some of Burroughs’s novels.

“He was a very brilliant writer who, when he was quite young, was knocked off his bicycle by a lorry and his spine was injured. He knew that he wasn’t going to have a long life and therefore writes with this extraordinary freshness and vividness of apprehension of a world that he’s likely to lose quite soon.

“He also kept this amazing journal, which was published in a very badly edited edition 30 years ago, in which he records, especially during the war, his tantalising encounters with soldiers and American G.I.s — boys stripping off and swimming in rivers. He had no money and lived in a garage apartment with this young man called Eric Oliver. Their love letters were published, actually, and edited by an American academic last year. But he’s an absolutely marvellous writer, partly because of his indirect and unabashed description of anything that interests him; he can move from describing a beautiful boy to describing a beautiful antic clock. It’s a hungry apprehension and he’s someone very much worth reminding people of.”

5. Edmund White — A Boy’s Own Story

“When I first read A Boy’s Own Story, I wrote a rather snooty review in the TLS, which afterwards I was very ashamed of. But I think that the book startled me in some way by showing this completely new thing that you could do — that you could write both very beautifully and finely and also completely unprecedentedly frankly about the experience of growing up gay. It was a combination that one hadn’t really seen before, that complete self-exposing candour and this marvellous literary imaginative vision. It was a really important book. Embarking on that first book of what would become a trilogy and deciding that he was going to write this very personal auto-fiction when he had no idea how it would have ended three books down the line. The whole thing, then, is a sort of adventure and seen through very personal eyes; its interest is only partly that it’s a chronicle of those decades. Its real interest is that it’s seen through the eyes of this very literary imagination.

“There’s a section in his autobiographical work, My Lives, called “My Master”, which is one of the most astonishingly frank things that I’ve ready by a major writer writing about themselves. I think it must be unprecedented in its candour, and I think some people rather threw up their hands and thought they were being told things that they didn’t strictly need to know. It is amazing, and you get underneath it, as you do very explicitly in A Boy’s Own Story, this sense of loneliness that this almost manic sexual appetite is fuelled by. It’s very powerful, but done with this limpid clarity. I do think he’s a major figure, and it saddens me when I hear that some of his books are harder to get hold of or when younger gay readers seem not to know about them.”

The Sparsholt Affair is now on Picador.