written by MAX WOLF FRIEDLICH

This story appears in i-D 375, The Beta Issue. Get your copy here.

August 2017. I move to Los Angeles. I am 22. I am here to become a successful television writer. I am coming off a break-up (my fault) and the end of a situationship (my fault). All my friends are back in New York, having sex with each other. I am alone, still not yet self-aware enough to be lonely.

I rent a room from empty-nesters in Los Feliz. I lie awake in their adult son’s bed, wondering how long it will be before I get to live in my brilliant future. I do not own a car. I walk a mile to LA Fitness to reread Branden Jacobs-Jenkins plays on the elliptical. I Uber Pool to Trader Joe’s to buy cauliflower rice and medium-firm tofu. I am an usher at the Dolby Theatre, where they host the Oscars. The first event I work at is Sam Harris telling a capacity crowd of V-necks and turquoise bracelets that Islam is inherently violent. My university roommate’s mum commissions me to write a web series about dog walkers. She introduces me to her manager. I sign with said manager because her company represents Chief Keef. I get invited to Chief Keef’s Halloween party. I fire the manager after four months. My university roommate’s mom calls me “an ungrateful little cunt.” I am living in a parody. I am not sure of what, exactly.

I meet Riley Keough’s producing partner. She asks what I am working on. I show her a meme I made. She says I need to meet her friend. I meet him at the Le Pain Quotidien on Larchmont. He is the coolest guy ever. He has a King of the Hill tattoo. He was Shwayze’s DJ. I make a joke about the record label Captured Tracks. He hires me on the spot. I neither understand nor care what the job is. I am wanted.

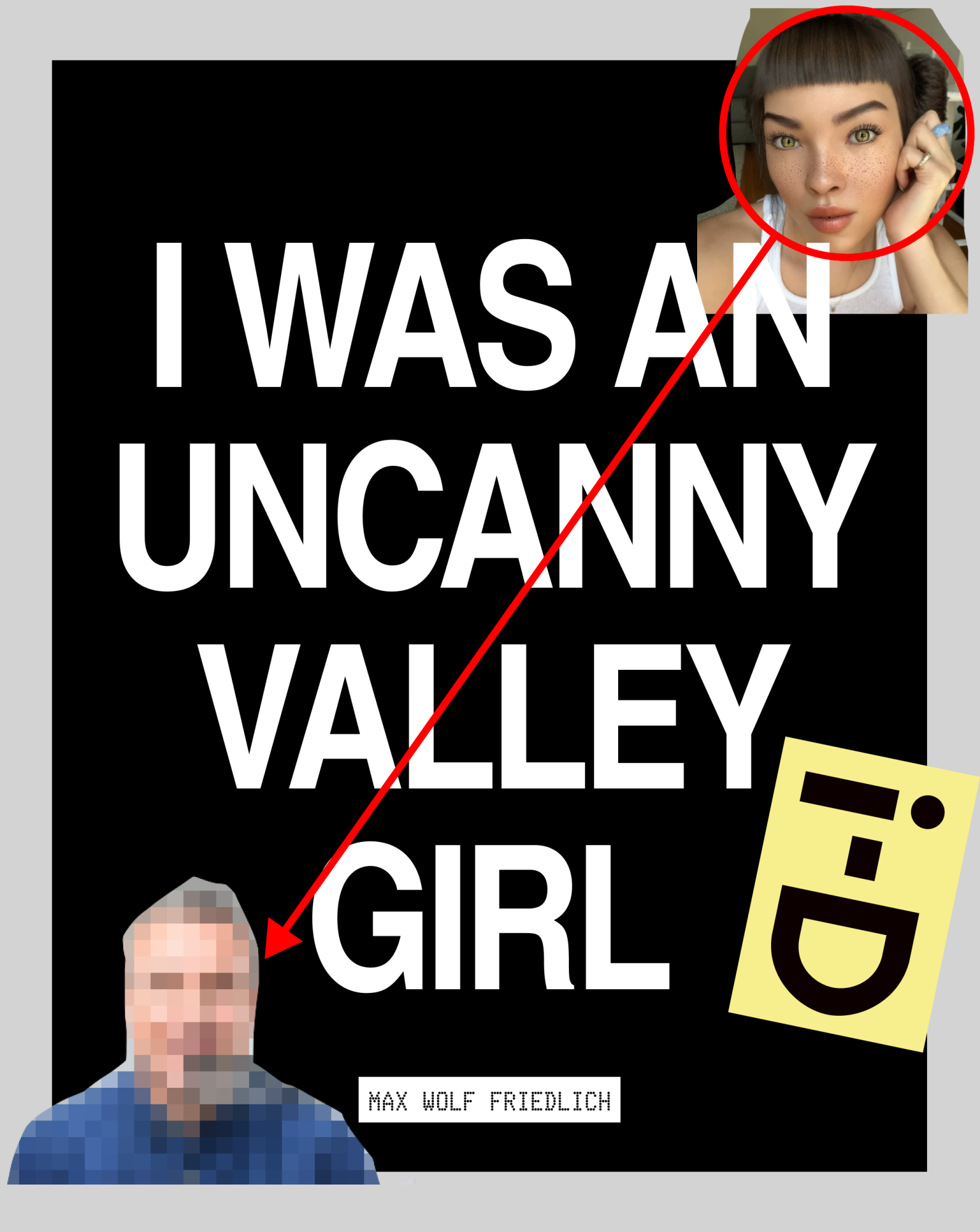

Apparently, I am now “story lead” for an influencer named “Lil Miquela.” I am in charge of her lore, of honing her voice. Miquela requires a story lead because she is a fictional character: a digital body transcribed onto real photos. Her face is designed to perform well in the Instagram algorithm––freckles, fringes, and racially ambiguous skin. My boss says we are building “decentralised Kendall Jenner.” Miquela will be better than any human celebrity, actually. Because she will use her platform to speak out on issues that matter––transphobia, racism, misogyny. He is telling the truth, but I’m not sure if the things he says are true. Either way––Volkswagen wants her for a campaign. Marni sends her a bag. Brands are excited at the idea of a woman who can’t say no.

Miquela’s followers are desperate to get to the bottom of her. Dozens of earnest “Are you a real person?” comments adorn every post, strangers chanting in unison, praying to an entity they neither love nor hate, but feel compelled to understand. With every @, every act of passive devotion, positive or negative, they manifest her marketability. As long as she remains a novelty, Miquela will grow. My job is to keep her new, forever.

More literally, my day-to-day job is to write Miquela’s captions. Online, the exchange rate for the written word is zero. If analogue talk is cheap, internet speech is free. I make her whoever we need her to be. Suddenly, millions of people are reading the words I put in her mouth. My boss confides that the long-term goal is to create a social-media-based cinematic universe, the “new Marvel,” with me as Stan Lee. Miquela’s account is hacked by a MAGA influencer named Bermuda, who works for an evil AI company, culminating in the reveal that Miquela is a robot. The Cut follows the hack in real time. She is on CNN, named a Most Influential Person on the Internet by Time magazine. Despite being a 23-year-old Jewish man, I am the internet’s most mysterious 19-year-old It girl. Every day, dozens of people beg to see my tits. Still, more tell me to kill myself. I have made it in Los Angeles!

In the wake of the viral hack, TechCrunch investigates. In an April 23, 2018, article journalist Jonathan Shieber reveals to the world, and to me, that I work for a Sequoia Capital-funded start-up valued at 125 million dollars. It turns out I am not a maverick creative changing storytelling––I am one of the lowest-paid tech bros in the country. I never wondered where the money was coming from because where does the money for anything come from? I now understand that, in America, 8 out of 10 times, the answer will be “a VC firm.”

Soon after the TechCrunch piece, my co-worker fucks up. She sends me an unedited photo of the model playing Miquela. I post it. My boss panics. Without novelty, we are nothing. I am told to do damage control. I spend 22 hours straight on Instagram muting phrases like “we saw your real face.” I disappear into the comments. I am neither me nor Miquela, but a bot programmed to suppress the obvious truth: That neither of us is actually a robot.

I am too tired to have a proper panic attack, so I read our DMs. An account claiming to be a 16-year-old in the Philippines says there are days he feels so depressed he can’t move. Miquela inspires him to keep going. I tell him he is my bestie. I tell him I have felt how he feels.“Wow, I can’t believe you responded to me! Are you a human???” I delete our interaction. I wonder if any of what we both said was real. Can a fake person have a real conversation?

In the coming months the story falls away. It’s too hard to integrate brand partnerships and narrative. I get fired in January 2019.

Today, Miquela is 22 years old, with 2.4 million followers. My cool boss sold her to an NFT “lab”––recently under investigation by the SEC––that runs on “the power of play.” I don’t know what this means, and I’m certain they don’t either. They made her partner with an “environmentalist AI.” If you tag #CleanItUpAI on your socials, there’s a chance she will Cash App you 50 dollars. In May, they gave her leukemia as part of a sponsored campaign to encourage stem cell donation. A human being could never. Get well soon, queen.

Everything I scroll past, be it a New York Times article or a celebrity break-up, has become Miquela to me: Business as usual masquerading as progress, a pitch deck wearing a G-string. Behind all these giant tech companies is some lonely boy stuck in Los Angeles without a car, hired to make profiteering slay-the-house-down-boots. It is all storytelling. The digital economy––and the regular economy, actually––runs on myth-making, on the belief in heroes and villains. And like any story, there are writers.

I was an Uncanny Valley Girl

"Job" playwright Max Wolf Friedlich penned one of the buzziest Broadway shows in recent years. Before that, and despite being a 23-year-old Jewish man, he was the internet’s most mysterious 19-year-old It girl.

Loading