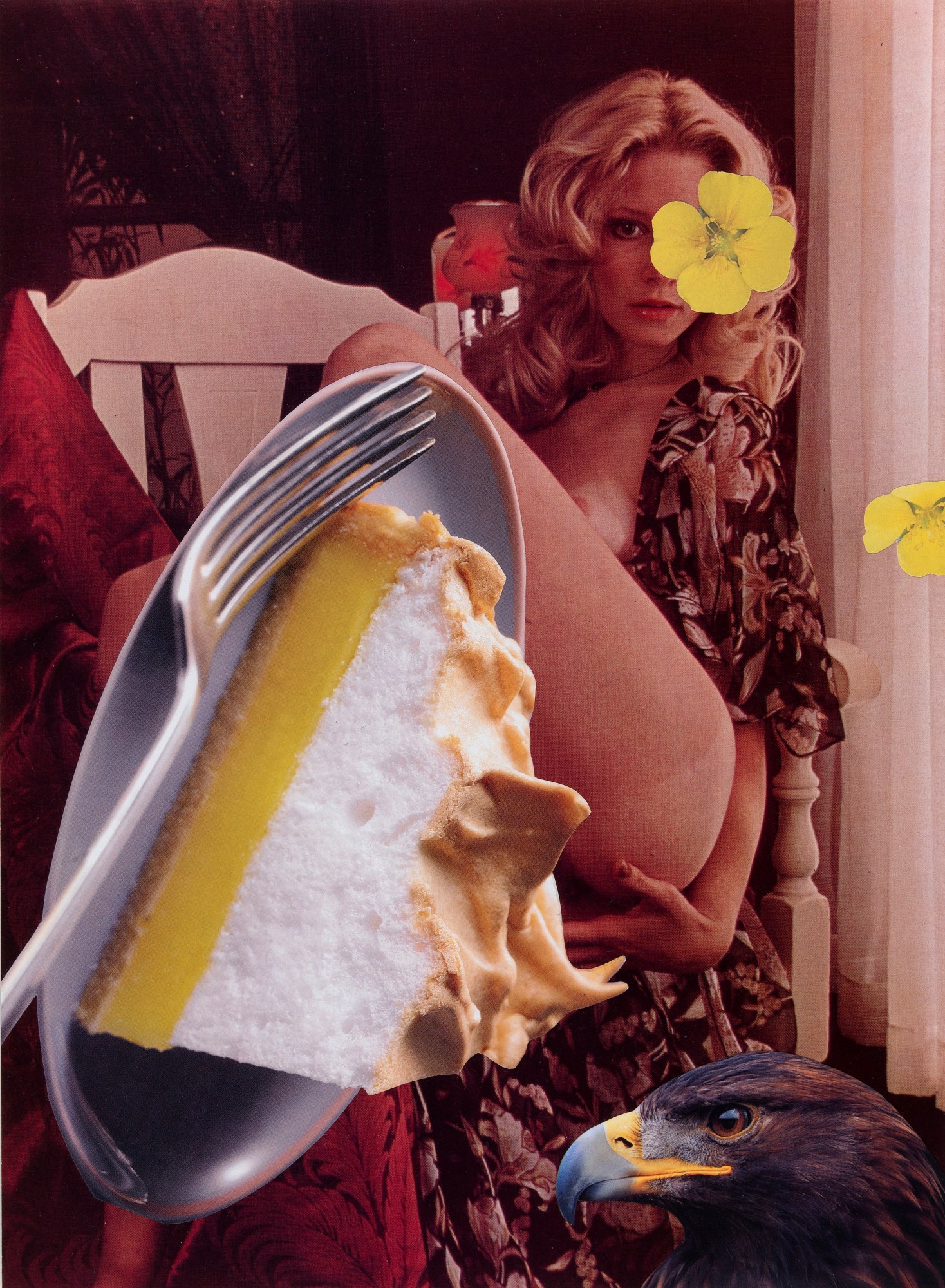

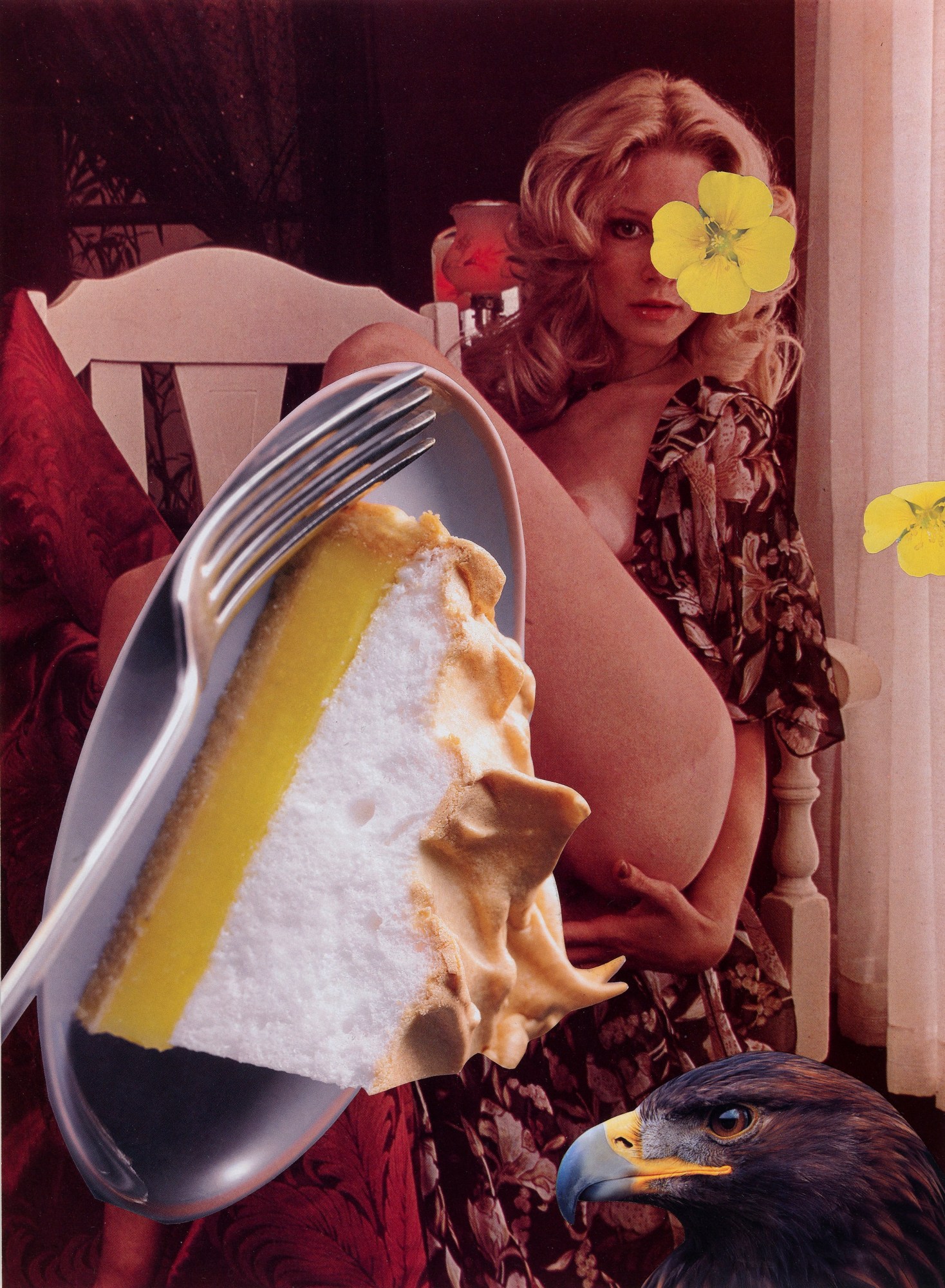

Linder Sterling is standing in front of an artwork of hers and speaking to me on the phone. It’s a photomontage of the cover of a gay porn magazine called Stroke UK. The piece, part of her new exhibition Ever Standing Apart from Everything at London’s Modern Art opening later in the week, sits next to Black & Blue, another porn magazine with a shared cheap, dated aesthetic. She takes a moment to photograph both pictures next to one another on her phone and text it over. Both covers have cut out roses across them; words like “hardcore” and “juicy” juxtaposed with delicate florals in red and soft pink.

Though her work is varied and multidisciplinary, for those unfamiliar with Linder, this piece might best exemplify her practise and the images she’s known best for. “Whether it’s Stroke UK, whether it’s an image from Vogue, these images are all so carefully constructed and quite fragile, and it does not take much to completely have the meaning spinning off in a completely different direction,” she explains enthusiastically. “It can take a cut-out of a rose, or a cut-out of a kettle, it doesn’t take much.”

It must be noted, to those who have not consciously experienced Linder’s work, it’s unlikely you’ve never seen any of it. Part of Manchester’s thriving punk and post-punk scene in the 1970s, she created the artwork for the Buzzcocks’s Orgasm Addict, and her cut-and-paste aesthetic went on to become a defining characteristic in the iconography of the punk era, and the whole scene in general. Many years later, her work has been accepted by the “art world” which, Linder stresses, was not even a concept until the eighties. It wasn’t until the mid-noughties that her work was acquired by the Tate. Then in 2018, her work appeared on billboards, posters and tube maps, as part of the TfL-commissioned all-female Art on the Underground series, at Chatsworth House — Linder their inaugural “artist in residence” — and at Nottingham Contemporary, which hosted a career retrospective.

Wandering around her exhibition for the first time, Linder discusses her work, her approach, the dark web, the Kardashians and more with i-D.

Tell us about Ever Standing Apart from Everything.

I hung the exhibition yesterday and I’m about to walk through it. I think that one of the themes is that of transformation. We’re still obsessed with makeovers and before and afters. I think the work that I do, you could almost tether it in Ovid or Homer. It’s all to do with tales of transformation and metamorphoses. My makeovers are quite monstrous. And they’re quite nightmarish. They’re not necessarily pleasant. The narrative in the show I suppose right now, is mostly encouraging one to transform.

This is your first solo exhibition in London for about seven years…

It’s a glorious moment. There was the 85 metres of billboard at Southwark for Art on the Underground last year. But this show… the works are very modest in scale. Working with found imagery, working with magazine pages. I am very aware at all times that the billboard was a very, very public display, and the works here are very intimate.

In the last seven years a lot has changed with regards to some of the content of your work.

It’s maybe not so much the content as the context. In the last 12 months I’ve made work for Chatsworth, I’ve made work for the Glasgow Women’s Library, there’s millions of copies of my tube map cover out right now, the billboards… The context has radically changed, therefore the audience has radically changed, and the scale has changed. I think a lot of the themes I’m dealing with, are themes I’ve been dealing with since 1976, they’re still extremely relevant. It’s not as if culture and society has radically changed. It is changing slowly, but everything still feels very relevant.

Do you get a sense of how younger audiences engage with your work compared to generations previous?

Wherever I go now, I often meet a new generation. They could be 14 or even younger, and they ask a lot of questions, especially the 14/15/16-year-olds. They ask ‘What was it like back then?’ and I feel a little like a war veteran, a gender war veteran. They’re always very, very eager to know what the context was of the early works and how they, as 14-year-olds, can have any sort of voice, how they can become articulate, how they can be heard.

This young generation, they recognise that perhaps something is missing culturally. Despite social media there’s still something missing, there are still gaps in communication. That seems to be their big thing. ‘What was it like?’ ‘What can we do now?’ I presume the younger generation are also wondering how we get into this mess that we’re in, and looking back to my generation for answers. The world is, in some ways, quite a mess right now and my generation are all culpable for that.

Last year, your work was shown at two major exhibition — one at Chatsworth House and one at the Nottingham Contemporary — propelling you far from your punk beginnings. In an interview with i-D before he passed away, Judy Blame said he’d recently met you and you’d said “our era of people who came through the punk thing, in the early 80s, you’d think nothing creative was going on in England at that time, but punk didn’t fizzle out, we were all still going, but the museums ignored it, the galleries ignored it, no one bought it, no one collected it”. How do you feel now that’s changed?

During that period of punk, the “art world” didn’t exist. That phrase was coined later in the 1980s, so it didn’t exist. None of us were eligible for any kind of arts funding, none of us had studios, there was grotesque unemployment in Britain. If you go back to the context of punk, if you photograph punks from 1976 it’s Britain at that time, that tells as much as the clothes the subjects are wearing. I think very very few of that generation has survived. Or at least, mentally intact. Judy passed away all too soon. In a way, I’m one of the few that made it through to a place we now call the “art world”. So many people ended up being farmers, or working in post offices or factories… they never got the chance to follow that creative trajectory.

So yes, I’m one of the lucky ones who did find a way of surviving. I suppose now it’s having the dream of the studio, the gallery, the collectors. I still marvel at that because that wasn’t my experience for so long.

What did it feel like at the time?

I think all of us, whether we were musicians or making visual imagery, deep down we all had a feeling something very important was happening… and then there are now various academics from various disciplines saying that those days were the last days of the British underground. It’s sort of hard to argue against that. I think we had a sense that what we were doing was very important, but that it wouldn’t last by its nature. Any sort of revolution never lasts. But a lot of that work I made was just hidden away in a drawer for decades. I mean, the Tate didn’t acquire a piece until, I think 2005-2006. For a long long long time, no one was interested in not only my work, but in the work of others. Judy Blame, with hindsight, we can look at his life and pick out highlights and think of him as just successful, but there were long long periods for Judy and others when the struggle to survive was all too real.

One of the most recent pieces from the new exhibition I’ve seen is the cover of a gay porn magazine entitled Stroke UK with two white men and a British flag. Can you talk a bit about this piece?

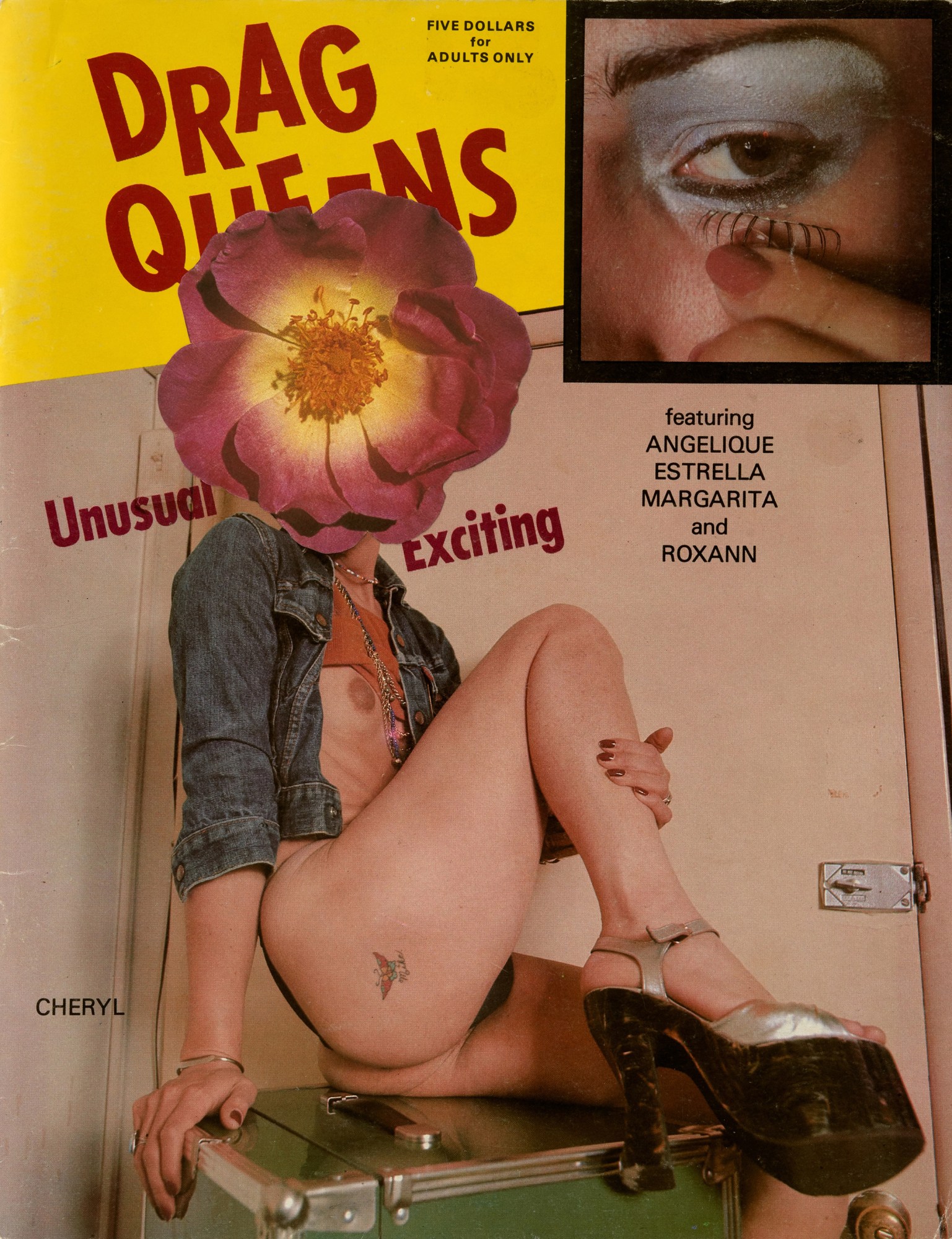

I’m going to stand in front of it right now. In the gallery it sits next to a magazine called Black & Blue. We have Black & Blue and Stroke UK, and it’s next to Claws magazine, it’s about “hussies grappling and wrestling”, next to drag queens. There’s a selection of magazine sleeves. So the only intervention I’ve made with Stroke UK is to put the roses on. So you’ve got the flags there, the strapline is “Bad mood fuck”.

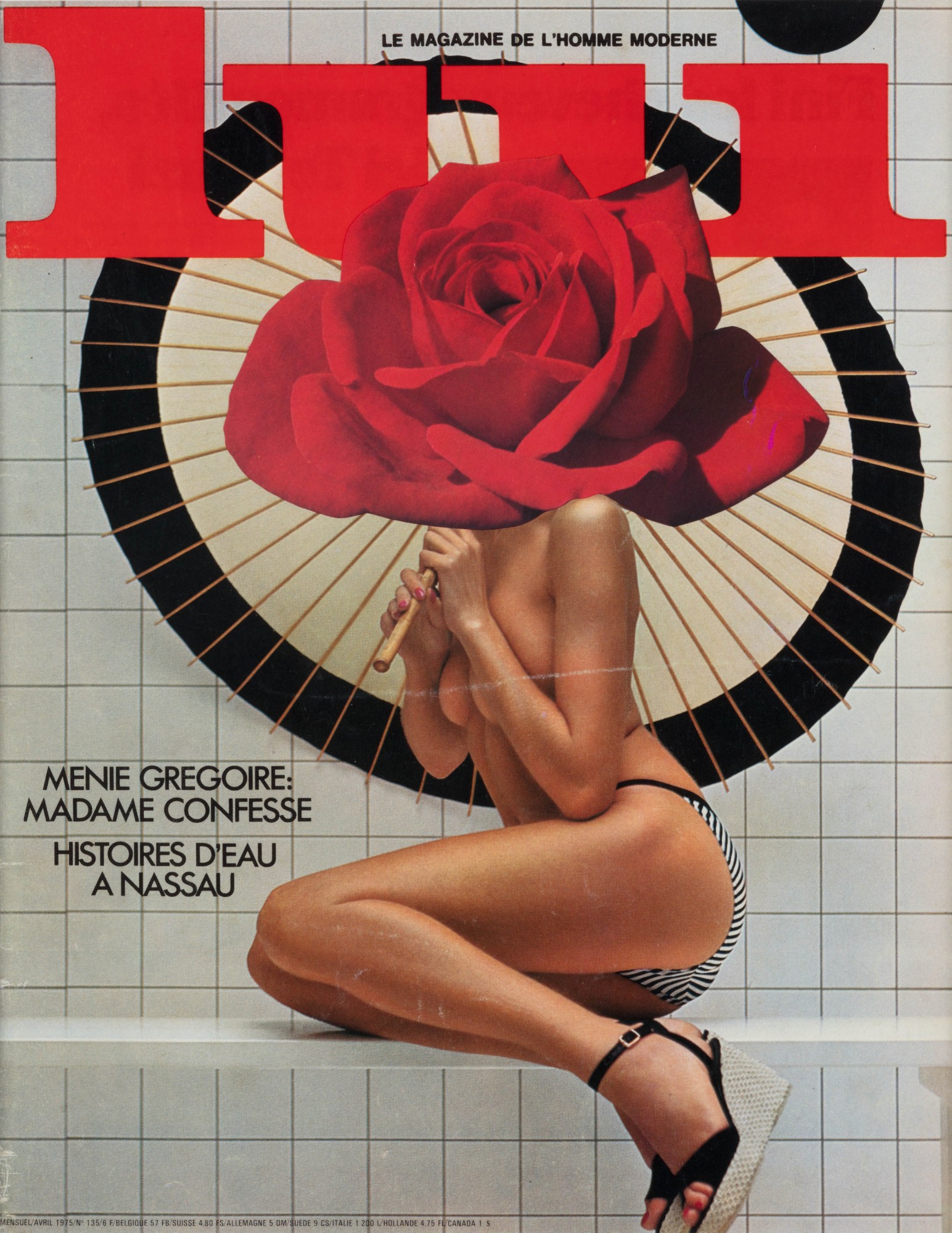

Everything I always do, I always to try and make the least possible intervention into an image. I work like a surgeon, with a scalpel, and I think the series of magazine covers — as much as anything, they’re rather like little biopsies from different periods. So Claws magazine — of women wrestling, I think from the 50s — it’s like seeing different cultures being grown in petri dishes. They’re from different periods. And yes, there’s a preservative of some kind, in the shape of a rose, but really it’s as much about the found object.

The material in this exhibition mostly comes from the mid-40s onwards, and it’s usually culled from so-called women’s and men’s magazines. This is pre-style press. The style press didn’t exist in the 70s, so there’s no i-D, or AnOther magazine or whatever. I mean, even now, in WH Smiths you’ll find women’s interest, men’s interest. It always fascinates me that music magazines are found in ‘men’s interests’, but I digress.

In the 70s, when I started, amassing material it was a lot easier, but I was just going and buying men’s magazines and women’s magazines. It’s about looking at the female figure, and how she migrates from being dressed to undressed, i.e. from the pages of Vogue, to the pages of Playboy. So again it’s just that work in forensics, just tracing the representation of the female across various media.

There’s a series of works made from contemporary hardcore pornography, and they’re montaged with contemporary catalogues for modernist furniture. Both things are fetishised. Modernist furniture is now fetishised and salivated over so, in some ways you can still say I’m doing exactly the same thing I was decades ago.

Do you think your work has the power to shock as much as it did years before?

Ummm, well of course if I delved deeper into the so called dark web, I’m sure I’d be horrified, appalled and shocked by what I saw, so of course, of course one can shock. People say fashion photography borrows a lot from the language of pornography, and yes it does, but it’s softcore. A lot of the Kardashian aesthetic to me comes straight from softcore pornography, so that’s not shocking — well, the Kardashians are shocking for the wrong reasons. You can still shock, it depends where you look. I often do not have the stomach to look where I need to look to truly shock.

Are there any parallels between now and the days of punk?

I hope there are. And if there are, I probably don’t know about them, by their nature. John Savage and I made a fanzine called The Secret Public in the mid-70s. The whole idea was that revolt and rebellion had to in some part happen in secret. Today there seems to be this collective urge to share everything within seconds, whatever one’s thoughts are. So I hope there are really radical — radical as in positive and creative — movements happening, then I won’t know about them.

Where do you find your inspiration these days?

I’ve been using pigments for the first time in years. Using pigments again, looking back to a British surrealist called Ithell Colquhoun, who lived completely off-grid and we know very little about her, she developed a technique called Mantic Staining, with enamels, and I’ve been using that technique recently. I get very very excited about that. Because I am so proficient at collages now there’s a huge degree of control over the images I make. But when I use pigments and the Mantic Staining technique, then I have zero control, and I get very excited about that. That’s where the inspiration is coming right now. Scale, colour and the fluidity of pigment is really exciting right now.

Linder, ‘Ever Standing Apart From Everything’, 1 February – 16 March 2019, modernart.net