“In the scene you come across people in the generations above who would say ‘African music really took a bad turn in the late-80s, early-90s with all these synthesisers'” Brian Shimkovitz explains, with an understandably sarcastic tone in his voice. Ghana brought us Highlife and because of Kofi Ghanaba it brought us African jazz too, but Brian has forged for himself and many others a career in peddling music dismissed by his elders through his blog and record label Awesome Tapes From Africa. “They’d say ‘Ghana’s interesting but the music’s not that dope anymore because they’re using drum machines’, but I kinda like that. The music which some people back home might have dismissed as too electronic, was the music that was really grabbing me. It was the music being played in the clubs and the bars in Ghana, played in taxis and played on the radio and people just dig it.”

For a continent of over a billion people, the idea that all the music coming out of Africa post-80s is a ‘wrong turn’, is a statement that’s not only a gross generalisation, to adopt this rockist attitude, it’s somewhat insulting.

Ghana itself is a country of just over 28 million people who speak 11 different languages. It’s a country of dramatic diversity and a place that prides itself on being a melting pot of different cultures, backgrounds, beliefs and ethnicities. From the Nzemaa speaking communities in the Western region of the country to the nation’s capital Accra, Ghana is a diverse nation in many ways, from its drastic changes in landscape and wildlife to its strong traditions and the music which they fuel.

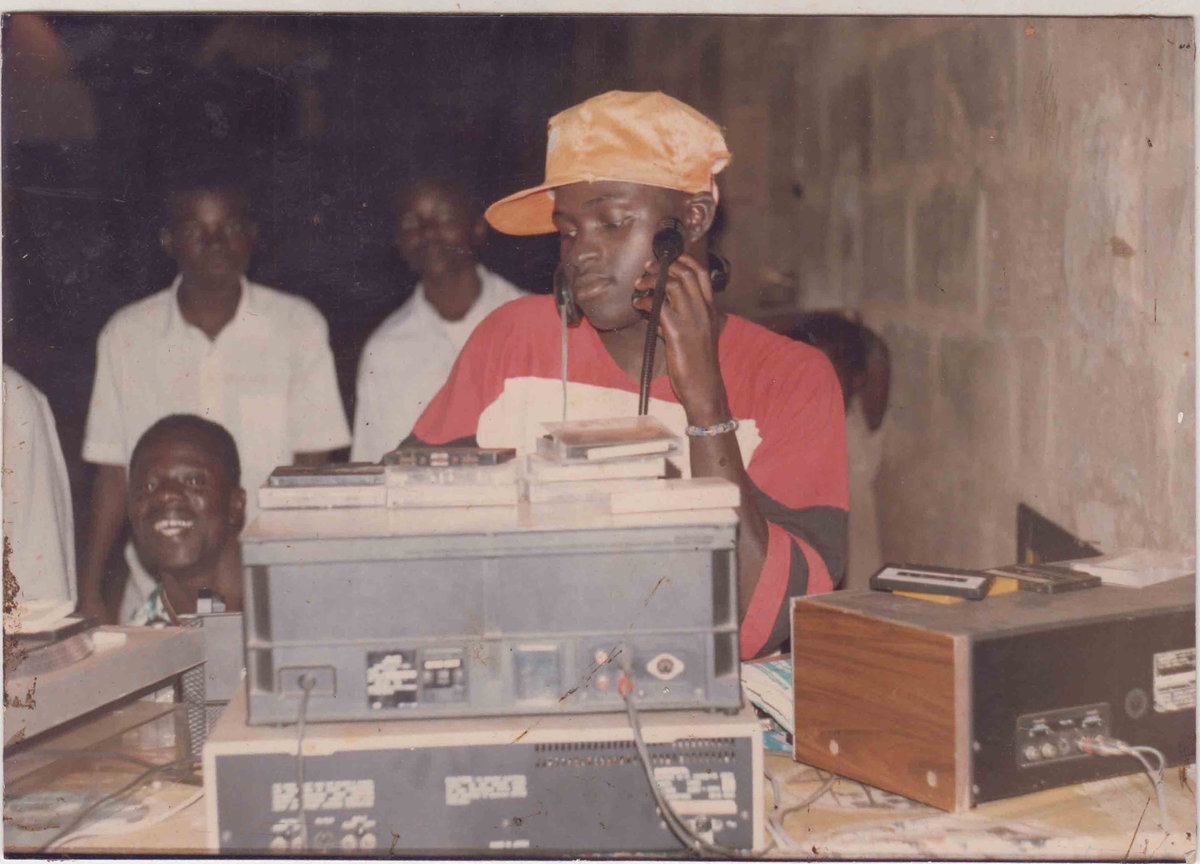

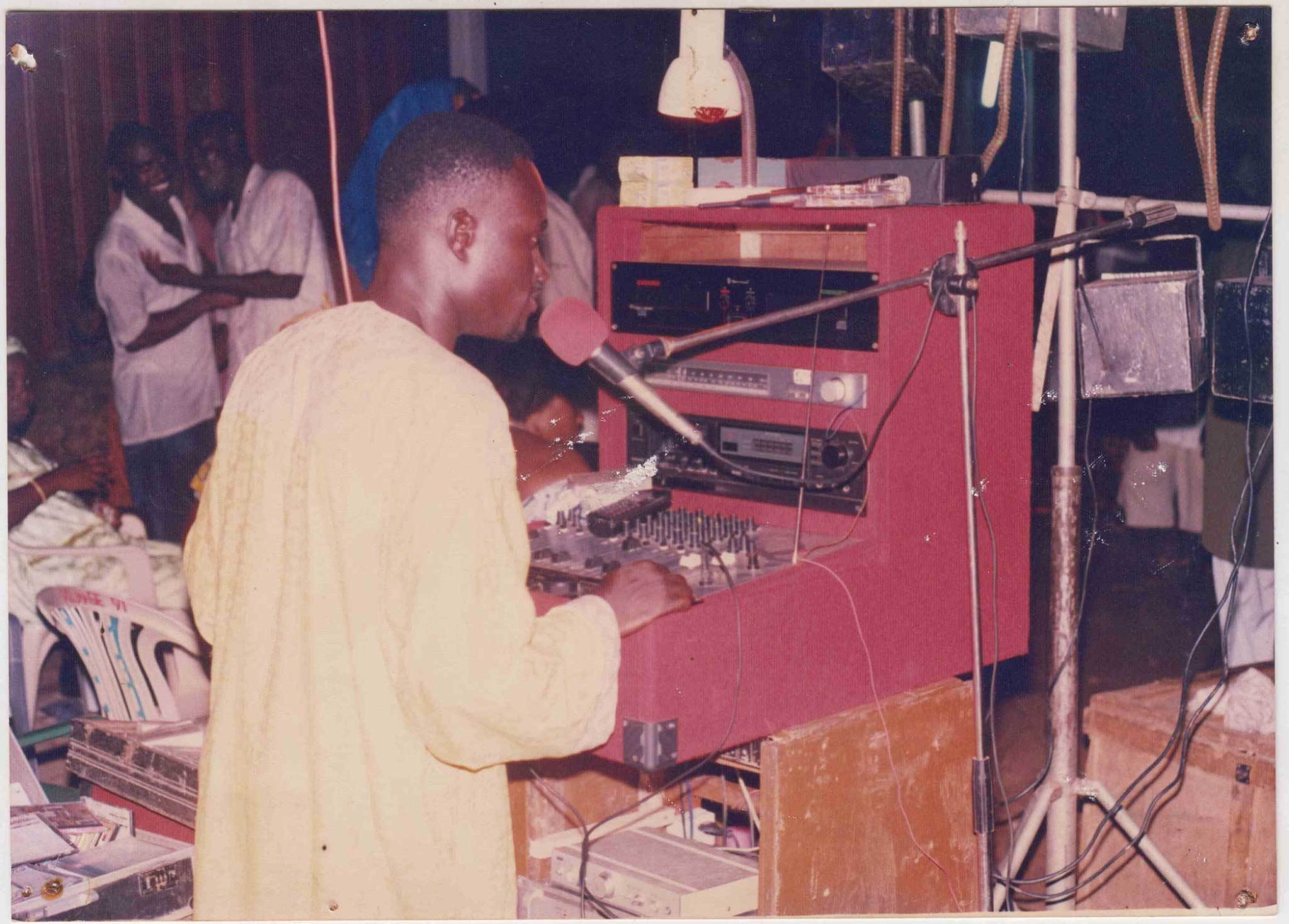

Over time those traditions merged with new sounds coming into the country from across the globe to form new movements. In the late 80s Ghana grabbed hold of the electronic beats emanating from the west and turned those into a new dancefloor-lead musical identity for the country. It created a one-of-a-kind dance music culture which came to embody the spirit of the country and through its lyricism and energy, helped encapsulate everyday life there. “What keeps people dancing, not sleeping, and playing music for three or four days non-stop are the funerals” begins Ishmael Abbey, otherwise known as Accra’s DJ Katapila who made his name playing those funeral marathons. Ghanaians do things a little differently you see. In Ghana funerals are a reason for celebration along with the more typical birthdays and weddings. They are a way for DJs to rise through the ranks by associating themselves with the biggest, loudest and bassiest soundsystems which, in DJ Katapila’s case, were Mobisco Sounds and Risky Sounds.

“Everybody was in a competition with each other” he explains. “You could have a record and when you have that song you wouldn’t give it to anybody. Mobile spinners would have different disco lights and equipment and the other soundsystems would watch your car arrive. If you have a big car it proves that you have more equipment. Sometimes I would sit on top of the car so the people could see me before we arrived and come to the dance.”

There’s a very DIY, somewhat romantic attitude to Ghanaian dance culture both past and present that is reminiscent of the free party days of acid house. It’s openness, simplicity and potential to unify are, as Brian mentions, things that “if you’re Ghanaian you can probably recognise and grab onto”. With the foundations of its dance music culture in Highlife it is something that Ghanaians can always feel nostalgic about, from generation to generation.

“Almost anybody can show up to these funerals and drink and dance and pay their respects” says Brian. “There’s definitely a fancy club scene there but whereas in London or Chicago a rave is deep in some neighbourhood far away, there’s a lot of public stuff that happens across west Africa, if there is a ticket price at a dance people would be out front listening through the gates.”

“There are parties happening in stations, open parks and between houses on the road, a lot of funerals take up a road on a Saturday and block off the street. A lot of people live in housing compounds in Ghana so there’s a lot of stuff in people’s backyards or a courtyard. It’s very out in the open and everyone’s very involved in the music.”

Ghanaian dance music of today has its foundations in the Highlife scene, which began in the 20s as an aristocratic get-together for Ghana’s high rollers. But it had mass appeal and it swiftly became an urban craze which, after the country became an independent nation in 1957, would become the national music thanks to the socialist government’s heavy encouragement of indigenous music and bands. While a military coup in 1966 created an unstable fluctuation between military and civilian single party governments in 1993 a democratic government was formed and the formerly state-owned media was liberalised. This ushered in a host of private radio stations that sprung up across the country, bringing with them a lot of the mainstream house, techno and hip-hop tracks being played across America and Europe at the time and embedded themselves into Ghanaian music. With this huge coming together of different styles and different sounds why did this find a home in Ghana and with the Ghanaian people?

“I learnt from techno and house music,” Katapila explains. “Even though I didn’t understand the language it was the beat, the instrumentation and how it kicks. There is something in the music, it touches the soul. I make sure to play music that the crowd don’t understand but is very danceable.”

“The important thing to look at is that house music and techno is obviously black music” continues Brian. “That comes from Africa in a lot of ways. Africans in general who are involved in music and production are super aware of how most of the cool music in America comes from Africa.”

“Human beings by nature cannot stick to one thing, we appreciate change,” Yaw Atta-Owusu, otherwise known as the once mysterious musician Ata Kak, suggests. “Ghanaians want change, it’s a call for creative ability and that is why I’m doing my best to come out with something different to the Africans, the Europeans and the Americans. In that case everybody appreciates it because it is something that is somehow unique or maybe somehow strange. I want to be different, and that keeps me going.”

It’s good to see Ata Kak look to the future with his music as it remained relatively unknown until very recently. While many Ghanaian artists make their name in the nation’s DIY DJ circuit, Yaw had a very different rise to prominence, and whereas finding Katapila “wasn’t too hard because he had his phone number on the back of the tape,” Brian explains, it was a very different story for Yaw.

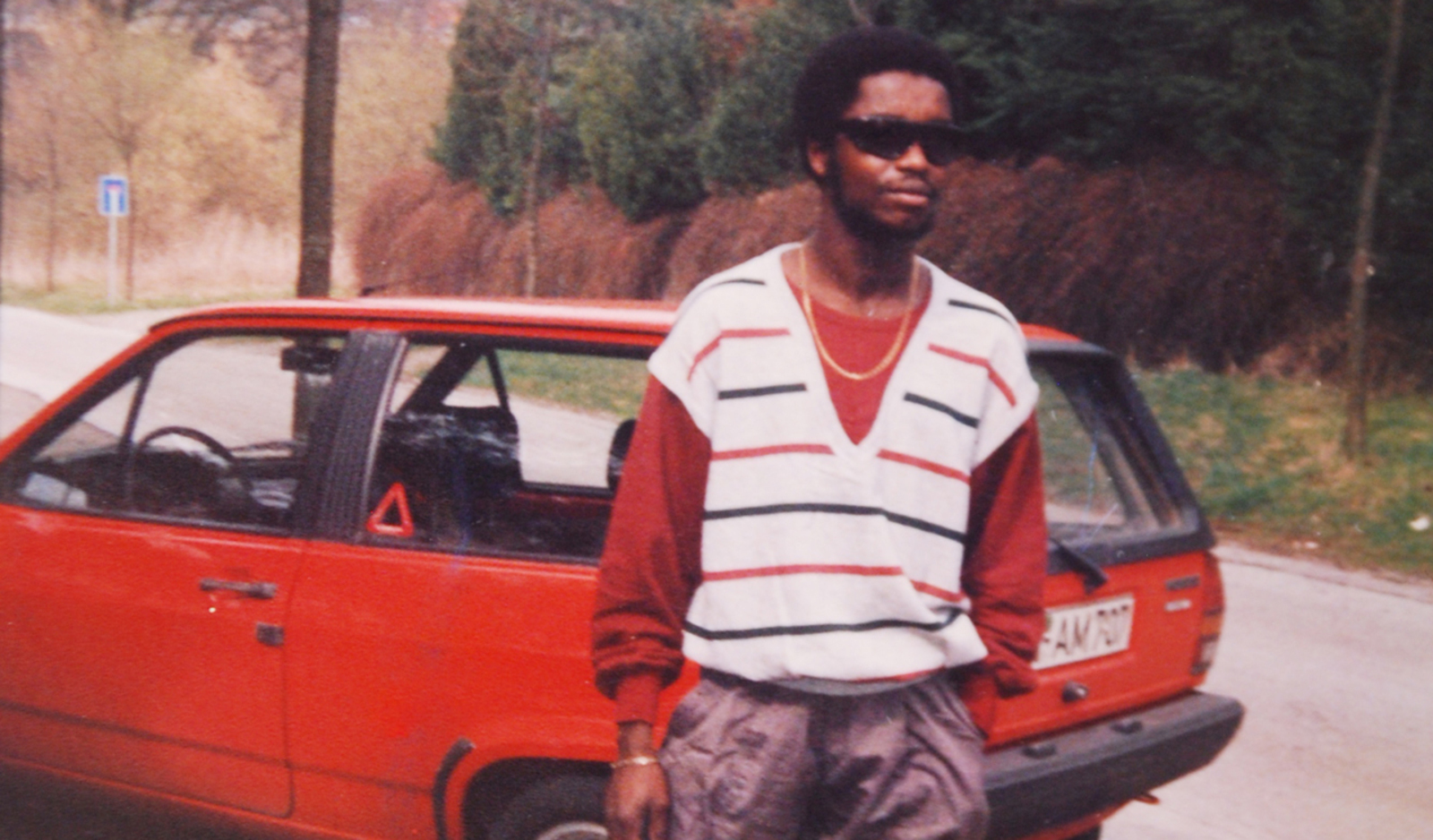

In the mid-80s Yaw had moved from Ghana to Germany with his wife Mary, followed by a 17 year stint in Toronto, Canada in 1989 where he created the fabled Obaa Sima LP with little to no knowledge of music production. 21 years passed between the initial release of Obaa Sima and its eventual re-release on Awesome Tapes From Africa, seven tracks of bedroom produced frenetic rap madness unlike anything you’ve ever heard.

Over several years Brian’s search for Yaw lead him from Los Angeles to Germany, through Ghana and then ended his mission driving through Canada with a BBC radio crew in tow who were documenting the lengthy experience. Eventually a chance Facebook plea through an unofficial Ata Kak Facebook page by Brian and the BBC team was picked up by his son who then put them both in touch. Until then, he was unaware of these efforts taking place halfway across the world, instead residing back in Ghana operating his own water drilling company until the call came.

“I was so disappointed initially because I couldn’t get any paper for the next release,” Yaw says, thinking back to his first incarnation as Ata Kak. “Finally I came back home to Ghana, I bought a drill machine and started drilling for water as my business. It wasn’t paying much because Ghanaians don’t have that much money and as I was running into debt I had to stop. Fortunately, Brian came in and everything changed greatly.”

“I was very young when I started recording my own music in my apartment in Canada,” he continues. “I thought here in Ghana I’d be very popular but up to now nobody knows me here, so when Brian called we were all overjoyed because finally, the sun that was behind the clouds for many years is coming to light again so we had to celebrate.”

For Brian, Ata Kak helped achieve everything he set out to do with his work as Awesome Tapes From Africa, but more importantly it is something that perfectly encompasses both Ghana and the African continent as a whole. “It perfectly defines what the blog is about, which is finding things that are not some sort of African version of American music, but a very African and local kind of music that has bits and pieces which those from outside the continent recognise and can grab onto. A connection, and Ata Kak perfectly encapsulates that.”

While Yaw has been travelling the globe with his live band, having finally reached a much wider audience he is more than happy to admit that he still remains largely unknown in Ghana, however this is something he isn’t planning to change anytime soon. “I’ve never performed in Ghana, it’s so strange that even here, right now nobody knows I’m a musician. Even my close neighbours have no idea what I do for a living.”

“Now I’m living a normal life because nobody knows me” Yaw goes on to say. “I can walk wherever I want to walk, say whatever I want to say, nobody knows me and I’m an ordinary, nice guy but once I become popular all of this will change. Suddenly, when I’m in town people will know me and I wouldn’t be able to live a normal life again and that scares me.”

There’s an undeniable ethos shared by Ghanaians that the music is not for the performer, it is for the people and both Ata Kak and DJ Katapila share that mantra entirely. “When I’m singing and I’m on stage performing I don’t do it for myself. Even though I enjoy what I do it’s my duty to entertain the audience” says Ata Kak. “It’s like a high to me.” It is this spirit, that welcoming of diversity to build something new and share it with the world which drives Ghana’s unique dance culture. “I’m proud of who I am, I’m proud to be Ghanaian and I’m proud of all the other things that I do” says Yaw. Finally, after all these years, we can welcome him and his culture the same way he has ours.

Credits

Text Jack Needham