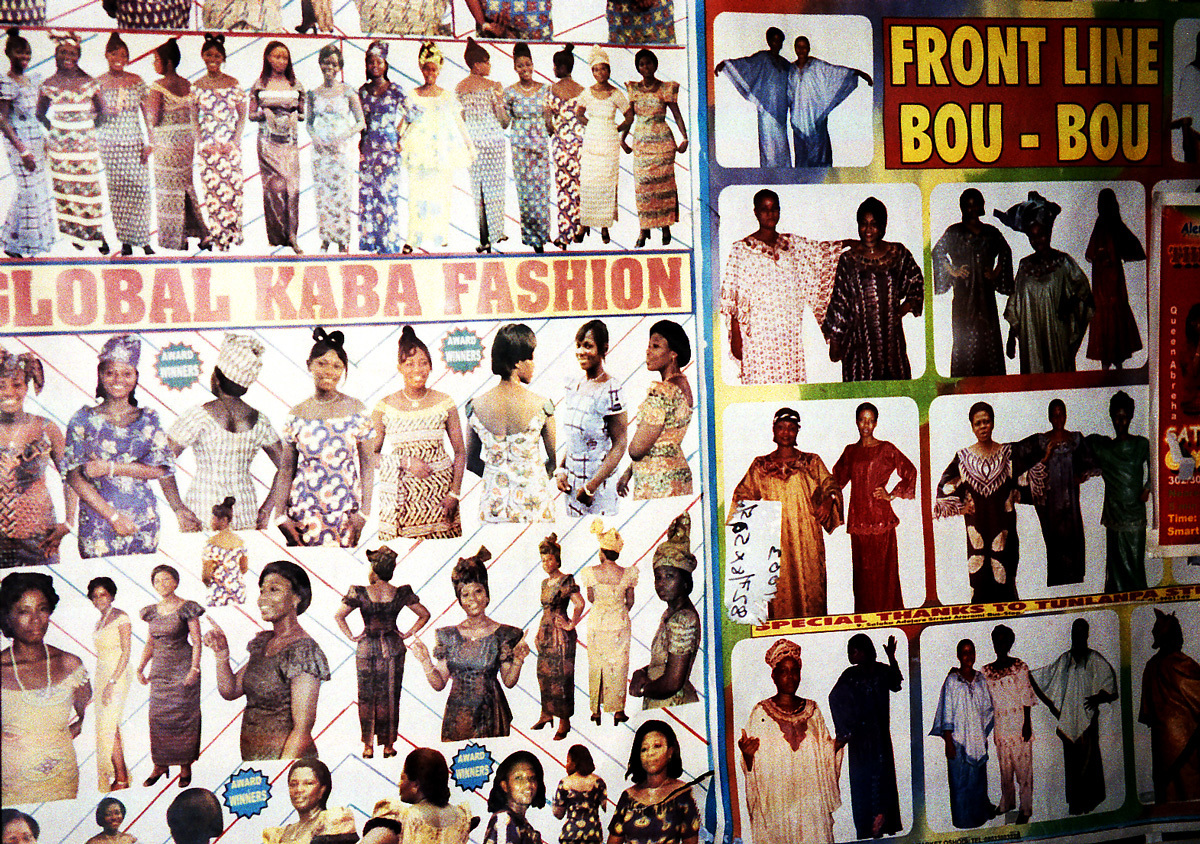

Liz Johnson-Artur is in Brixton’s Windrush Square, surrounded by people who are making the most of one of the last evenings of summer — they’re eating, drinking, listening to music. Sometimes, they wander over to where we’re sitting, in the far corner of the square, to take a closer look at one of her portraits, which will be projected onto the walls of the Black Cultural Archives every night for the next week. The images openly celebrate black communities, black aesthetics, and black creativity; exhibiting them in this particular public space, with all its history and resonance, feels like a deliberate political act. Liz explains that her tribute to South London is part of an ongoing battle for the soul of the area. “Representation is really important in this struggle. You have to stand up and do something — and people are fighting what’s happening. Tonight, through my work, I want people to see themselves represented as being physically part of this place.”

Does she consider her work political? “Yes, of course.” Then, after a thoughtful pause, she clarifies, “I take what I do very seriously, but I wouldn’t necessarily have called it political unless you asked me that question. My work’s political in the sense that it’s about communicating, about being able to understand people’s struggles, to learn how we can live together.”

Liz came to London in the 90s and has had a studio in Peckham for 25 years. She’s been obsessively recording black communities all over the world ever since. She talks at length about London, about ‘regeneration’ and the impact it has on the creative potential and energy of a city. Gesturing out into the night, she says, “There’s a cafe that I really like in the market here. I’ve been going there for 20 years. And you you can eat well, and drink, chill out and watch TV, all for five pounds. That must sound really simple but it’s very important to have these places in a city like London, in a community like Brixton. Places like that are getting eaten up.” It’s easy to often feel quite desperate about the situation, but Liz strikes on a tentatively optimistic note. “I’m not a negative person. There’s always the official story and there’s also the story on the street, you know what I mean? Somehow, people always know how to survive.”

This last sentence really resonates, because Liz has spent much of her career telling stories about survival and resilience on the streets of South London. And so, it’s important that she’s giving her work back to the people and the places that they came from. It’s something that she gets very passionate about. “I want to show the pictures to the people they’re taken from. And this is a nice space because it’s private, but it’s also public. The people that I photograph… I wouldn’t say they don’t go to galleries, but I would say they don’t get approached by galleries, and they can be quite intimidating spaces.”

The pictures Liz is showing in Windrush Square are part of a lifelong project which she calls the Black Balloon Archive. It’s clear that, as well as the political desire to create powerful images of the black diaspora, Liz is motivated by a personal desire to make connections with communities which, until her mid twenties, she barely knew existed. Growing up in Eastern Europe and Germany, she tells me that she only begin to consciously explore her own blackness much later in life.

“I’m going to be 52 this year and for half my life, I had barely had any contact with black communities or black culture, because I only grew up with my mom, who’s white. But, growing up, I did have this one picture of me, my mom, and my dad. And, looking at this photo of my dad, I realized that through photography you can access different cultures and places. So, pictures were important in terms of discovering things about myself, and about other people.”

When Liz first arrived in London, as an outsider, photography was her way of gaining access to these exciting new spaces. “Photography is a really personal thing for me. Having a camera with me was my way of asking if I could come into these communities. The first real thing that I did was take pictures of a black church in Elephant and Castle. I’d never seen anything like it before. And I started to think that if they let me in, maybe others would, too.”

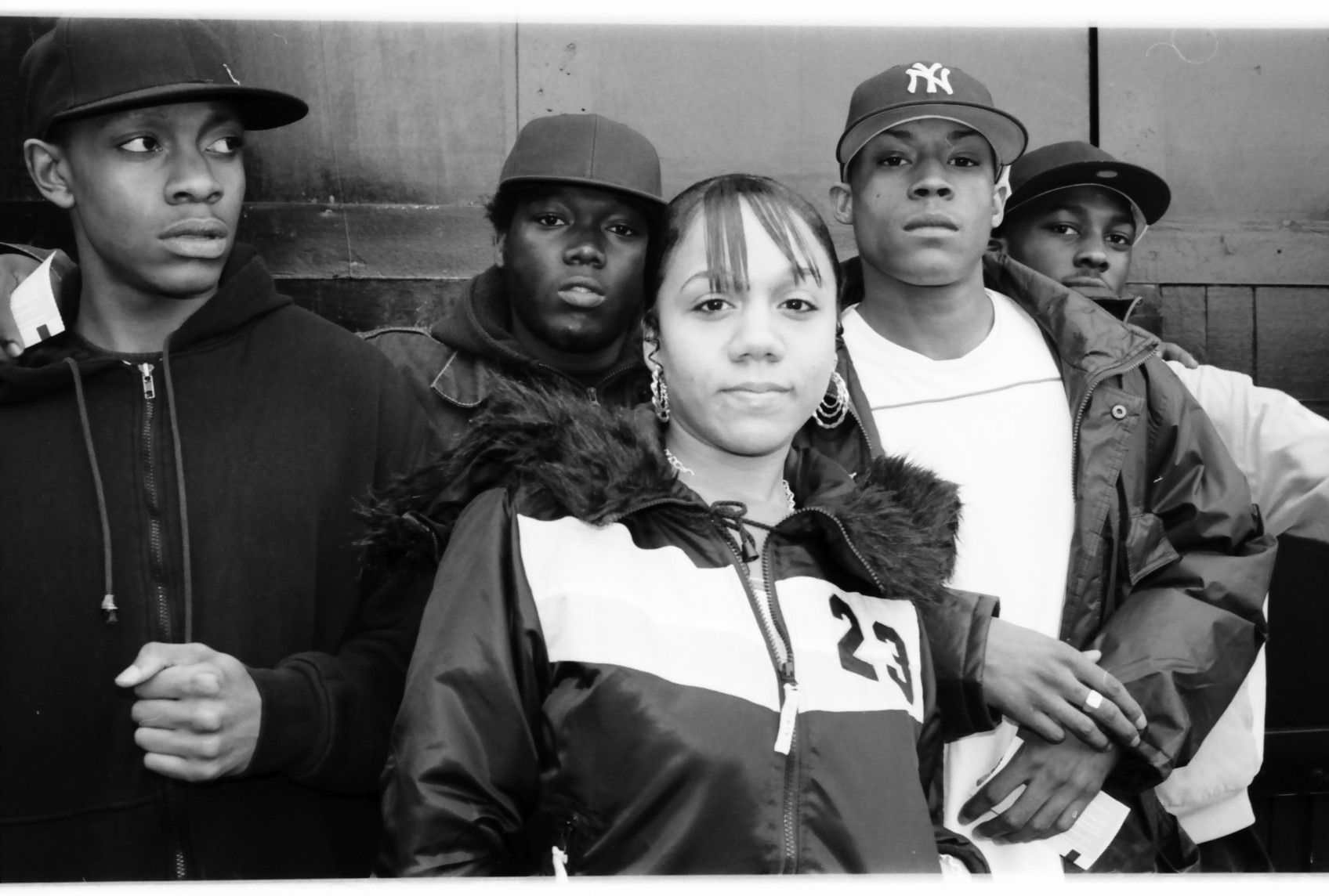

It’s been a long time since a pastor in Elephant and Castle let her take photos of his congregation. But that way of working — being truly grateful to the people who let her into their spaces, making close connections with her subjects, and working collaboratively — hasn’t changed. There’s a real intimacy about her photos because of this: a sense of being behind the scenes, feeling like you’re actually on the night out with the gang of girls at the back of the 98 bus. “For me, taking portraits is a very personal, one-on-one experience,” Liz says. “It’s a collaboration, even if it’s only a very brief encounter.”

Collaboration is another core principle of the Black Balloon Archive. She tells me that she’s always conscious of “how people want to represent themselves.” There’s a clear level of respect for the way people present and curate their own public image, which is really important when the media often show us images of black bodies — particularly those of young black men — that demonize and dehumanize them. “There’s a sense of pride in how people display themselves. It’s why I like street portraits, because I think there’s a real presence that everyone has.”

Liz tells me that, ultimately, she got into photography because she “wanted to record the normality of black lives and black culture, which is something that isn’t often reflected in the mainstream media.” She resists one-dimensional images and flat stereotypes. The portraits on the wall behind us, changing every few minutes, celebrate the normal and the extraordinary, the vibrant and the banal, the nuances of each individual life.

Credits

Text Niamh McIntyre

Photography Liz Johnson-Artur