Greta Bellamacina

National Poetry Day: Who Gives a Fuck? was the name Greta Bellamacina gave to a short film she made about Ezra Pound. She’s convinced that we all should give a fuck about poetry if we want to keep it alive in a world where cuts to the arts are rife and spaces to embrace them are being closed. “I wanted to make a point that poetry, if political, doesn’t sleep”, she explains. Greta sees all art as a political act, a form of resistance. “Poetry is a democratic way of bringing the world to rights, anyone can write a poem and publish it,” she says. “It’s uncensored. It’s unforgiving and forgiving, an antidote to a soulless materialist world. Poetry is a community of people painting a shadow on the world for everyone to see, beautiful, harrowing and gentle.”

Greta’s no stranger to using the arts as a rallying cry. Her 2016 documentary The Safe House: A Decline of Ideas, was a call to action against the cuts and closures of Britain’s libraries. “I think the future will be a dark and culturally barren place without these spaces,” Greta says. “The internet is not enough to educate the next generation, and it’s a myth that every student can afford to have a laptop, wifi, books, their own room.”

“The poverty divide is real and it will continue to grow if we don’t give every child a chance to dream and learn.” Without the space to embrace art, our world would be a much more horrible place.” As a mission statement, it resonates. The constant background noise of daily bad news and gloom and the cacophonous roar of the internet where it seems we’re always being warned of an impending apocalypse can make it hard to stay cheerful. But, Greta explains “art has the power to transport you somewhere else. Being hopeful in your message is the most radical statement you can have,” she says. “To push past the horrors of the world and remember that we are full of light.” Text Roisin Lanigan

Sang Woo Kim

Sang Woo was the first Korean model to saunter down a Burberry runway. We’ve lost track of how many editorials his machete-sharp cheekbones have graced. And while the model-come-artist inevitably learnt a lot about angles and light from his posing days, one lesson stuck above all: “It challenged my commitment to my art,” he tells us. “I think it was a necessary hurdle for me to take in order to be able to really pursue what I wanted.”

That said, he’s not entirely sure what propelled him down this path: “If I knew why I paint or create images then I guess I wouldn’t be doing it. It’s not just about enjoying and loving art, it’s about understanding why you’re doing it.” His works are a visceral collection of layers, textures and mixed-media. One day he’s blocking thick stripes of oil on a canvas, the next he’s juxtaposing figures with a flower-lined basement for Coach in his motherland of South Korea. “Many have said that my paintings are abstract and textured,” he explains. This process of deconstruction — often painting over or re-contextualising past work — is how he probes themes around memory, nostalgia and recollections. “I guess I could call it ‘recycling’ paintings, which portrays a timeline of my emotions.” So how does he know when a work’s finished then? “I think you just know when you know.” Text Georgie Wright

Faye Wei Wei

Faye Wei Wei was raised in the harsh grey of south London with, as she puts it, “nothing delicious for the eyes.” Perhaps that’s why she’s always been so obsessed with creation, so brilliant at dreaming up fantasy worlds in full colour. To a soundtrack of Arthur Russell, Björk and Mitski, the 24-year-old layers oil paints on canvas in a studio full of flowers, Japanese seashells and plenty of jasmine tea. The result? Beautiful dark fantasy tapestries shrouded in love, symbolism and poetry; black velvet flowers, mysterious women in great dresses, hearts, plants, devils, leopards, giant snakes and androgynous merpeople.

Faye paints until the tension between her body and the infinite bodily space of the canvas has disappeared. “You kind of dip in and out of that space; attacking the picture plane, embracing it, kissing it…” she says. “You know when it’s over because there’s a feeling like you’re no longer bound up in that dance. Then you step back and look at the image you created… and that’s the most wonderful feeling in the world.” If she could have her work hung in any fictional place, it’d be “inside a Kubrick film,” she says, smiling.

Although she credits late American painter Cy Twombly for making her want to be an artist, Faye admits that really, she does it all in the name of making her father proud. Earlier this year she spent time living in the desert of New Mexico on a painting residency with art friend Omari Douglin, who she calls “a magic boy!” It sounded heavenly.

Reflecting on time spent in Athens for a recent show, Faye remembers the beauty she discovered there and the inspiration she took from it. “We went up to the peak of a mountain, as if closer to the gods. The belly of the church, at the very tip of the mountain, had walls covered in paintings…” she beams, “like El Greco, folds of velvet with fish lying within every dip. An old lady with eyes like blue planets gave me a wink, it broke my heart.” Funnily enough, Faye Wei Wei, you break ours. Text Frankie Dunn

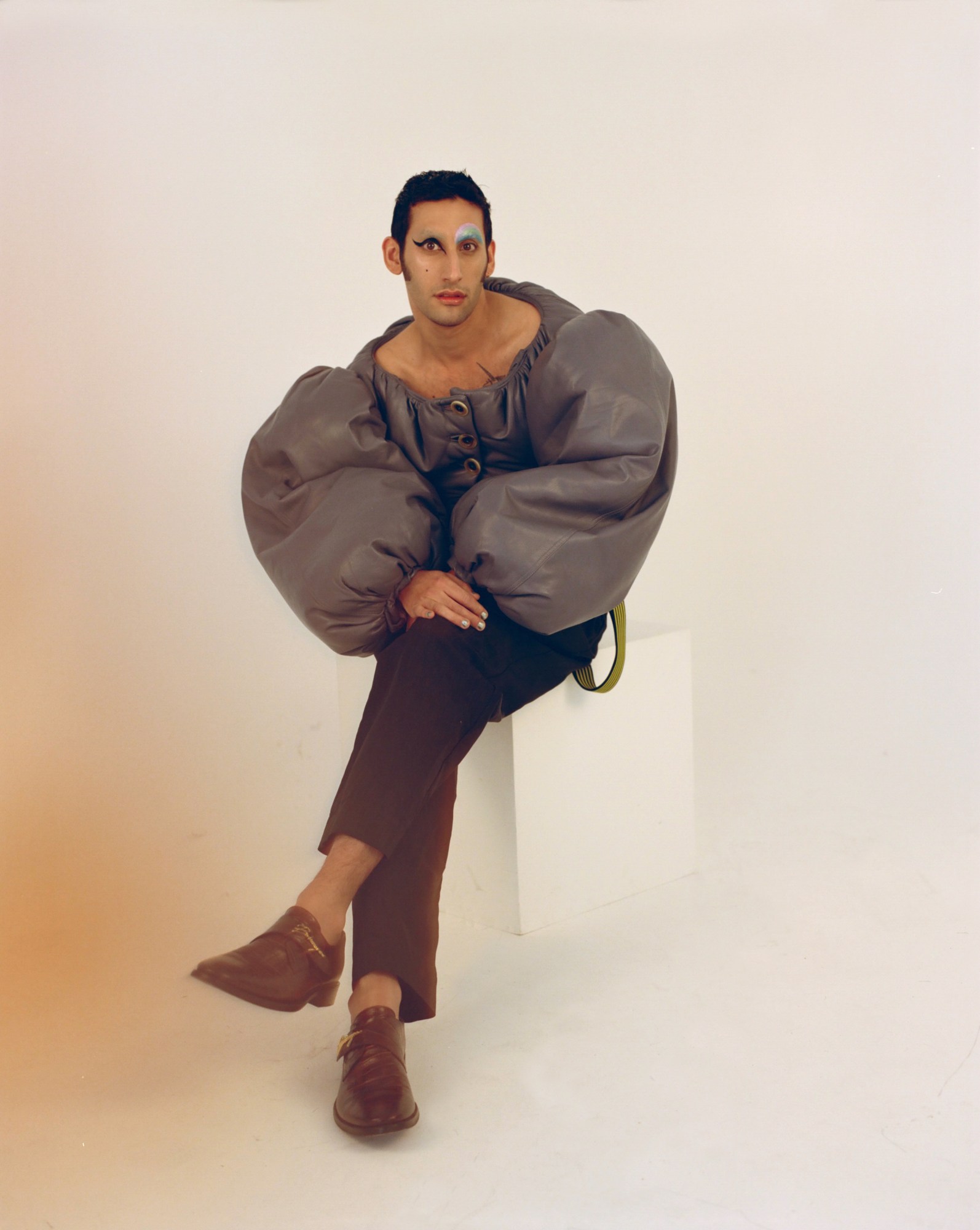

Amrou Al Kadhi

Artist, activist, actor, filmmaker, drag queen — Amrou Al-Kadhi is a man of many talents. But before he was any of that he was a happy little boy growing up in the Middle East, in awe of his mother (“sort of like a drag queen herself”) and the powerful femininity of his culture. Then, as a queer teenager, his relationship with his identity became blurred and painful. It was the discovery of the art of drag, his technicolour female persona Glamrou, and his sisterhood celebrating drag collective Denim that helped him fall back in love with his heritage and unite the different facets of his identity. “The most reparative thing that Glamrou has done for me has been allowing me to fall back in love with my Muslim heritage”, he says.

“During my adolescence, I experienced devastating rejections from family and religion. I completely exiled myself from my family and the community at 16. Turning into Glamrou, I’m able to reconnect with my Muslim heritage through the femininity of Arab culture. In many ways, I dress up as my mother as a way to save the image of her I loved as a child, before we grew apart.”

Glamrou was born before the advent of RuPaul’s Drag Race, the show that took drag from counterculture to the mainstream. But the RuPaul school of serving looks and lip-syncing for your life isn’t the only avenue for young queens. “Although I love the show, it’s rooted in American capitalist notions of drag,” Amrou explains. Instead Amrou uses his work as a way of champion Muslim and queer voices in a media landscape where those voices are marginalised and underrepresented. “As a queer Arab in Britain, I have to constantly narrate my own experience in public forums so that it doesn’t get skewed or erased. I need to have agency over my story.” Text Roisin Lanigan

Olly Shinder

I first met Olly Shinder at a party, wafting seamlessly through a crowd of people. Some exotic clubland creature you just couldn’t ignore. Or would want to. Who was he? What did he do? It didn’t really matter. Back then his hair was a crop of bleached blonde curls, and he was wearing a vintage Margiela suit. He’s over that look, now. These days he’s sporting a shaved head, dog’s collar and cyberpunk boots.

Olly grew up in north London. He spent his youth gorging on the city. Dining on the finest it has to offer. “It’s perfect for someone like me who is into all the weird shit that’s happening across the different neighbourhoods. There’s also so many great exhibitions and I’ve met lots of inspiring people.”

The first thing to really make an impression on young Olly was Test Site — Carsten Höller’s 2006 slide installation at the Turbine Hall, and the Jean Paul Gaultier exhibition at the Barbican. “That had a real impact on me,” Olly says. “I was just shocked about all the different inventive things Gaultier had done; his use of colour and how he mixes ideas of sex into his clothing so tastefully.”

Just 18, Olly has his whole life ahead of him, whether that means forging a career as an artist or designer or maybe even both. For now, though he’s focusing on fashion with a foundation course at CSM. “I love making things,” he says. “I think you can tell a lot of stories with clothes. Right now I wouldn’t say my style is quite there yet, as I’m only beginning, but I’ve been doing some quite experimental stuff, exploring unconventional shapes and fabrics. I like to toy with stereotypes.” He pauses. “I’m just doing what I want and what feels right to me.” Text Tish Weinstock

The White Pube

“We write about how we feel,” says Zarina Muhammad, one half of cool young art critic duo The White Pube. “There’s no point trying to squeeze into these tight confines of what an art critic should be,” adds the other, Gabrielle de la Puente. They met at Central Saint Martins studying a BA in Fine Art. They’re both 23-years-old, born just seven days apart — Gabrielle in Liverpool, Zarina in London. They speak quickly and finish each other’s sentences. They laugh a lot, are incredibly sharp, and are very, very tired of the elitist old, white world of art criticism. The pair wanted a space where they could write about art on their own terms, so they launched their website at the end of 2015. Free from the shackles of sponsorship or advertisers, The White Pube can write what they want, about who they want. It offers a new, youthful art writing, replacing impenetrable, impersonal texts with amusing soliloquies and whimsical emoji summaries.

They write on their phones and write the way they speak to each other, setting the tone of each review by explaining how they feel. “I have an anxiety problem,” Gabrielle begins one review. “The physical effects of this precarious transitional stage I’m in post-uni trying to make The White Pube lyf into My Actual Life has curdled my body n brain.”

Another central focus is dismantling the notion that identity must play a driving role in decoding the work of minority artists. As a woman of colour, this is incredibly important to Zarina. “Critics should focus less on identity and more on the value of the work itself,” she says. “Sometimes you need to be privy to an experience to write about it.”

The White Pube aren’t in it for the likes. This isn’t a vanity project. Nor are they in it for the money. In fact, if they didn’t live at home and have jobs on the side, The White Pube wouldn’t be sustainable. Instead, they’re doing it out of vocation. “For so long we were seen as irreverent, and we felt irreverent,” Gabrielle says. “Now, when I say, “Hi I’m an art critic,” it doesn’t make me laugh as much, because that’s what we are.” They’re the radical art heroes we need rn. Text Tish Weinstock

Credits

Photography Liam Hart

Styling Bojana Kozarevic

Hair Hiroshi Matsushita using ORIBE Hair Care

Make-up Rachel Singer Clark using M.A.C (For Rosie, Hannah, Bianca, Greta, Lewis, Gabriella and Zarina)

Make-up Anne-Sophie Costa (For Amrou, Franziska, Gala, Sang)

Photography assistance Andy Moores

Styling assistance Louis Prier Tisdall

Hair assistance Keisuke Takano

Make-up assistance Rachael Freeman (Anne-Sophie Costa)