“I think South Americans are called the invisible community because everyone knows about us, but they just skim past us,” says Manuella Alvarez, one of the teenage protagonists in More Than Other, a new short film from Brazilian director Romano Pizzichini.

The notion of invisibility comes up often when discussing the UK’s quarter-million-strong Latinx population. A 2016 study from Queen Mary University analysing its size and social characteristics was titled Towards Visibility (it followed up a 2011 research paper called No Longer Invisible). Romano’s documentary finds the rapidly-growing community officially “other”-ed — excluded from the standard ethnicity categorisations on government forms like the census — and struggling to be noticed amid London’s vibrant patchwork quilt of immigrant enclaves.

It’s about to become even less visible. London’s two most important Latin American hubs, the Latin Village market in Seven Sisters and the Elephant and Castle shopping centre, are threatened with imminent closure — both front-lines in the losing battle against the capital’s ongoing gentrification and physical erasure of working-class communities.

The Elephant and Castle shopping centre is a 1960s hulk sitting inconveniently among the recently-minted skyscrapers and refurbished plazas of what was, until fairly recently, one of London’s more physically unwelcoming public spaces. The giant, choking one-way system that kept the centre isolated and unapproachable to the wider population — and thus affordable and viable for the tenants and communities that used it — is now partly removed and pedestrianised. Now the bulldozers are coming for the centre itself.

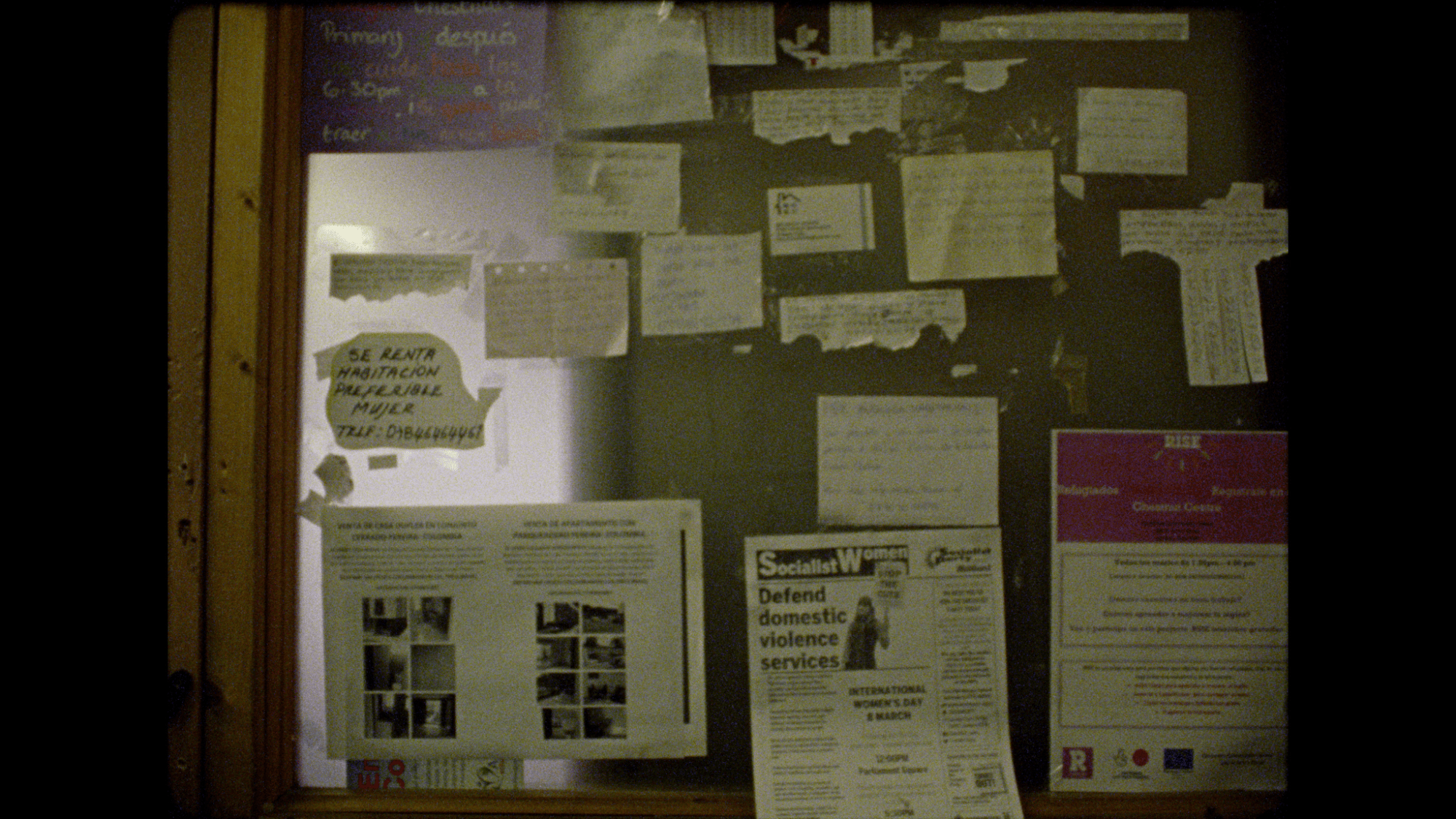

Though rendered unsightly by later additions — weather-beaten blue plastic cladding, a greying canvas canopy — the interior of the shopping centre retains some of its original, modernist-utopian elegance. It’s less a chain-filled mall you’d recognise, more a typical London high street with a roof on it. There are chemists and supermarkets, green-grocers and mobile phone repair places, charity shops and pawn brokers. There are diners that don’t appear to have changed much since the centre’s 60s heyday and units turned into art galleries, performance studios and community spaces. Mixed in among these are businesses that tell the story of the area’s unique ethnic make-up: Ecuadorian cafes; Colombian bars, delis and fashion retailers; international money-transfer providers with signs in English and Spanish. All will be gone, barring an unlikely last-minute reprieve, once the centre closes for good at the end of July.

Images released by the developers, Delancey, show what will replace the centre once it is demolished: airy, traffic-free public spaces, brightly-lit chain stores and a notable lack of wire-transfer facilities or Dominican bodegas. The plans talk vaguely of relocation funds and “securing alternative affordable space for shops, cafés and restaurants in the area.”

“It’s run down but it’s soulful,” says Romano, who first encountered the mall while studying film at the neighbouring London College of Communication. “I’d never been to Venezuela or Colombia but being there, even though it was slightly different from my own culture, the distance from home made it feel very close, and those differences dissolved.”

It was a combination of homesickness, fascination and puzzlement that his classmates seemed oblivious to the rich community on their doorstep that led Romano to document it. Initially hoping to set a fictional piece in the enclave, he struggled to find young Latin American actors and the funding he needed to complete it. “That’s when I realised a documentary has to come first, to start the conversation,” Romano explains. “[I thought] this needs to be done, so I might as well do it — I know some of the kids, I know the area, I have some insight. It came from a place of necessity rather than me seeing myself as a documentary filmmaker.”

Work began on the film, a collaboration with Rio-based production company Capuri and Breno Moreira, in the summer of 2018 — a time of unusual hyper-visibility for the community. The World Cup was on and people were wearing the football shirts of their, or their parents’, home countries. For Romano, it provided an excuse to approach, make small talk, and street cast for his new project. The result is an eight-and-a-half minute series of portraits of British-Latinx teens: Dylan, a 17-year-old MC who raps in Spanish and English; Bryan, an aspiring actor whose Colombian immigrant dad teaches taekwondo; Joshua, who connects with his family’s heritage by photographing the Latin Village; Kamixlo, a British-Chilean musician who mixes reggaeton and metal; Zharinck and Cecilia, who campaign for Latin representation and census recognition as part of the LatinXcluded advocacy group.

They are mostly second generation, with parents who arrived around the turn of the millennium, or as so-called onward migrants from Spain after the 2008 financial crash. They talk about balancing their Latin heritage with their London identity, the ethnicities they get mistaken for (Turkish, Indian, Middle Eastern, “mixed”) and the challenges of carving out a space for shared cultural celebration and pride. “When people move here for the first time they’re not necessarily thinking about representation or identity,” says Romano. “They’re thinking, ‘I want to have that life, or to create a better life for my children.’ But once their children are here then they start realising that they don’t really feel like they fit in.”

The documentary’s shot on film, giving a warm, nostalgic feel. “I wanted it to feel quite tender, intimate, a little bit dreamy because they were thinking about the future as well as looking back,” Romano explains. “I didn’t want it to be a harsh, ‘urban’ cliche.”

La Barra is a Colombian restaurant, housed in a railway arch just south of the Elephant and Castle shopping centre. There’s a Dominican restaurant upstairs, in the same arch, and a peluquera squeezed into the entrance way. Even on a midweek mid-afternoon, the restaurant is fairly busy: there are couples, teenage friends, a family celebrating a birthday. Romano isn’t a “typical” Latinx Londoner — he came here to study, he’s lived in Canada and Sweden as well as his birth country, his ethnic heritage is a mix of Brazilian, Lebanese and Italian — but then, who is? “You talk about a Latin American person in the States, you have a stereotype. It might not be true but you have an idea, an image in your mind, but here there’s nothing,“ Romano says. “Then you think about other cultures in the UK, like Jamaican. You have that dual identity… that British-West Indian identity exists and is really strong. But that population moved here earlier — so now it’s like these [Latinx] kids who are shaping what the culture will be: they’re defining it, they’re doing it all from scratch, there’s no template.”

And then there’s the simple fact that Latin American is an identity forged in diaspora, drawing from a vast population and geographic area: from the border with the USA to the southern tip of Chile, incorporating two continents and dozens of countries. As Romano says, “you become Latin American once you leave Latin America,” and it’s in the shops and restaurants of Elephant and Castle that the disparate nationalities come together and build something collective. “There’s a Dominican place, a Peruvian place, a Colombian place, a Venezuelan place, a Brazilian place around the corner,” says Romano as we step out of La Barra into the cold London air. “They have created a community and a safe space.”

Six miles north of Elephant, Tottenham’s Latin Village faces a similar fate. A collection of some 60 small business — Ecuadorian, Venezuelan, Colombian, Brazilian — operating in an old Edwardian department store that had stood empty for many years, it’s set to be demolished to make way for 40,000 square foot retail and residential development, a partnership between developers Grainger and Haringey council. Nearly 200 new housing units are to be built, none of them affordable. As at Elephant, traders have been offered alternative spaces nearby, but without guarantees against rent increases, many see the plans as an effective death sentence for the much-loved community hub. Compulsory purchase orders were given out last year, and evictions began last month — despite the best efforts of the Save Latin Village campaign. “There’s so many reasons for it not to be torn down, the only reason for it to be torn down is money,” says Romano.

More Than Other doesn’t offer solutions to the cleansing of London’s ethnic neighbourhoods, and Romano acknowledges the battle against developers’ millions, and underfunded councils trying to regenerate by any means necessary, is a “David versus Goliath fight.” Instead he hopes to screen his film at events as a means to uplift and celebrate the community it documents; to help strengthen the cultural bonds and amplify the voices of its younger generation, and to encourage outsiders to explore the vibrant London-Latin experience sitting, overlooked, under their noses. As Romano explains: “If people don’t know about the community, it’s easier for developers to just sweep it under the rug — like one of the girls in the documentary said, ‘they’d never tear down Chinatown.’”

Romano Pizzichini’s guide to Latinx London

Latin Village (Seven Sisters)

“If you’ve never been to Latin America, this is a great taste of it. Coming here is like entering another world. Amazing energy, people, food (don’t miss the Pan de Horno at Blanca’s). In here you’ll find restaurants, groceries stores, bars, hair salons and barber shops. It gets even more lively at night. Go there, fall in love, and help fight to keep it from turning into a Costa Coffee or similar.”

La Barra (Elephant and Castle)

“One of the area’s many great Colombian restaurants. This one stands out for the Dominican Pica Pollo, which some say is the best fried chicken in London.”

Brazilian Wax (various locations)

“A queer Latinx club night, run by Joana Nastari. Expect Live Samba, mind-melting pole and drag acts, cold fruit, caipirinhas and Brazilian homemade snacks. The next one is at Vault Festival on February 29. Joana says: ‘In a nutshell we are a group of people who are passionate about safe space, night life. I am queer, Brazilian and a former sex worker, and I wanted to create a space of joy and solidarity that people from these three identities and beyond could come to be free, be themselves, and meet other people from their communities. This party also was originally started to raise money for artistic projects and activist campaigns.’”

Distriandina (Elephant and Castle)

“Restaurant by day. Club by night, with regular reggaeton parties.”

Elephant and Castle Shopping Centre (Elephant and Castle)

“A meeting point, safe space and cultural gem of London’s Latinx community. Sadly, it will be shut down as of July. Go there to enjoy it while it lasts, discover an array of shops and restaurants, and become more aware of why we need to fight against social cleansing.”

Reggaeton parties (various locations)

“There are loads of these in London, but here’s an upcoming one for Valentine’s Day.”

See some stills from Romano’s documentary below: