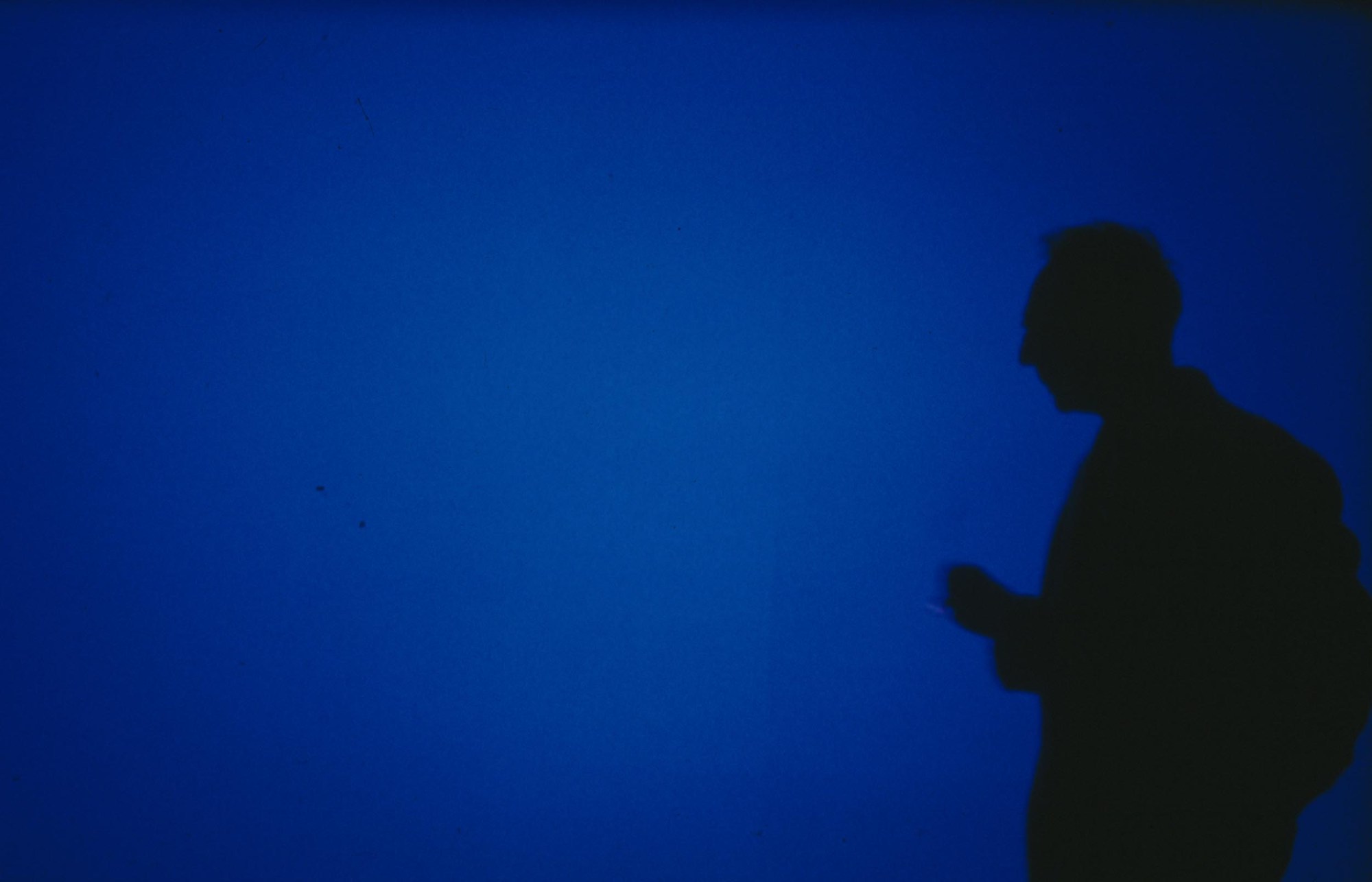

When a journalist asked Derek Jarman how he would like to be remembered in 1994, only weeks before he died from AIDS-related complications, the British artist and filmmaker answered that he would prefer to evaporate. “I wish I could take all my works with me,” he said, amused. “That’s what I’d like to happen — to just disappear.”

Luckily for us, this final wish didn’t come true, as a freshly-opened major retrospective at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin demonstrates. Marking the 25th anniversary of Jarman’s death, PROTEST! gathers some 150 works — many of which have never been seen before — spanning four decades and focusing on his practice as a painter, writer, set designer, gardener and political activist.

Jarman of course is best remembered as the maker of radical films such as Jubilee (1978) , a dystopian tale in which Queen Elisabeth I is catapulted to gruesome 1970s London’s punk scene and Caravaggio (1986), a fictionalised re-telling of the life of the Baroque painter. Weaving political commentary of the Thatcher era with pop-culture and historical references, Jarman staged queer stories in postmodern settings before any of these concepts had made it to mainstream consciousness. The British maverick also gave their first break to many then emerging talents, including Tilda Swinton, Joanna Hogg and Sean Bean.

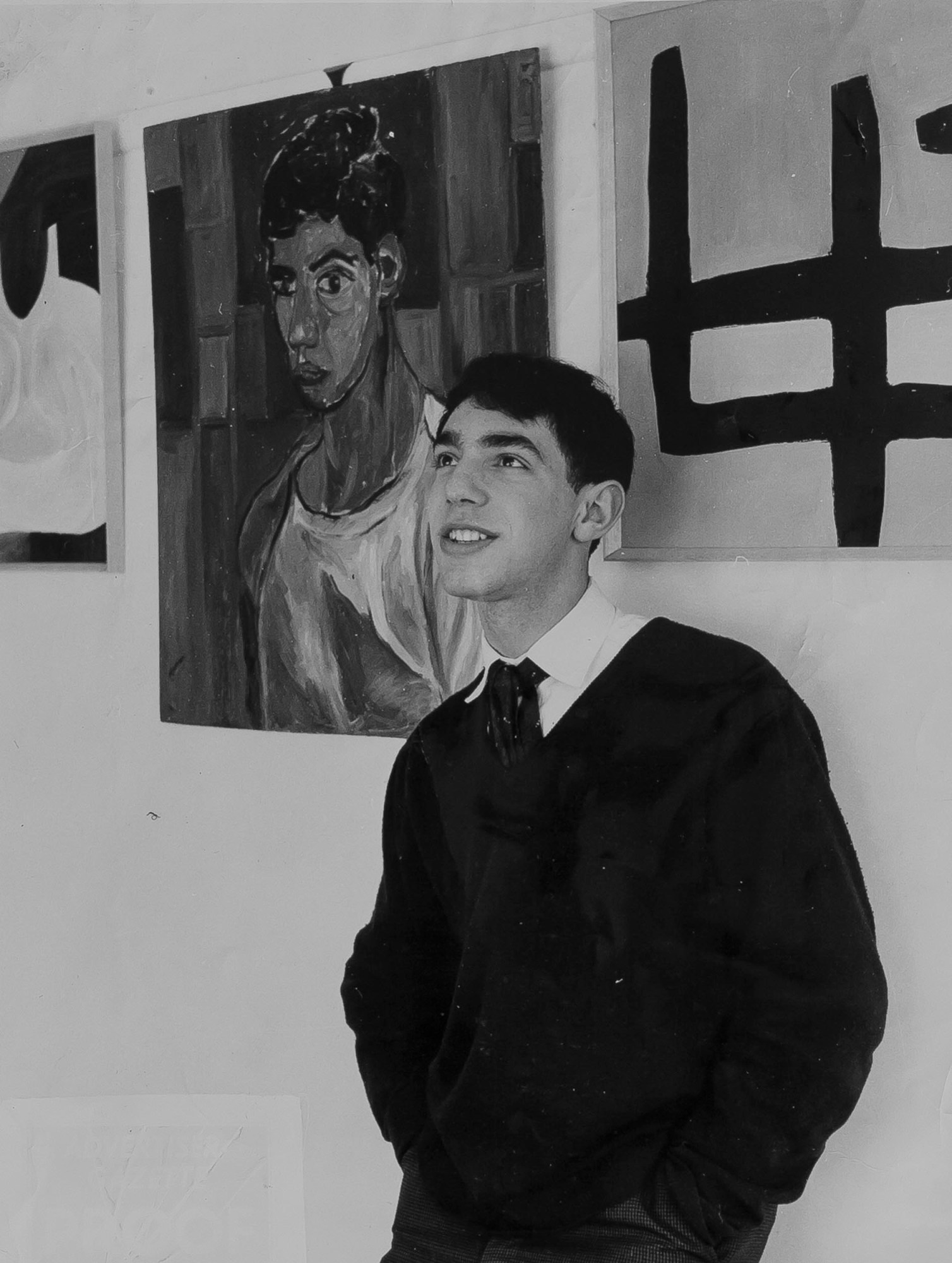

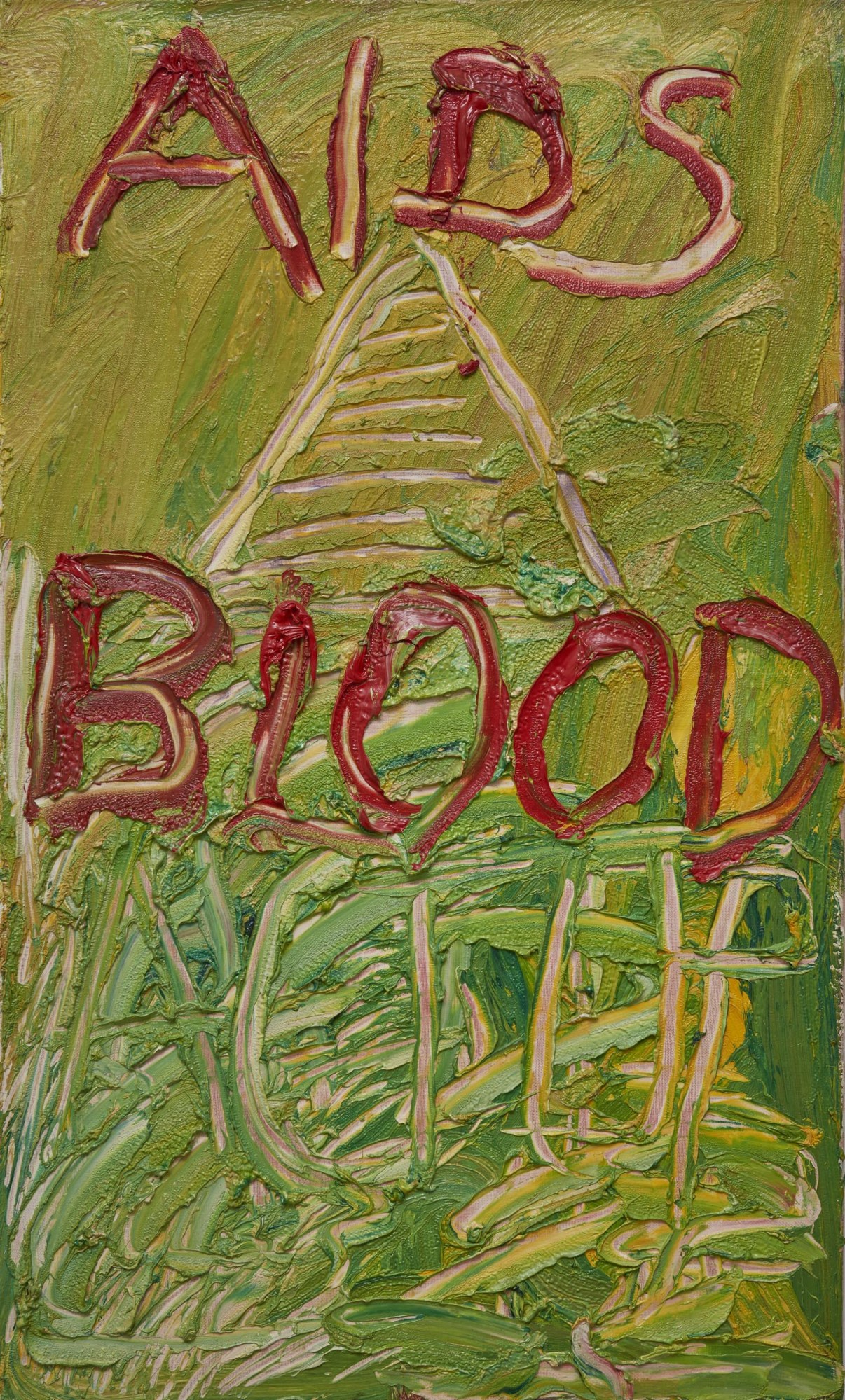

But what fewer people know is that the influential filmmaker was also a devoted painter. Trained at London’s Slade School of Art in the early 60s, Jarman was part of a group of young artists, including Patrick Procter and David Hockney, who embodied a changing mood in British art. Following an interminable legal dispute between Jarman’s former art dealer Richard Salmon and long-time partner Keith Collins (who died last year, shortly after the case was settled), a number of rarely-seen paintings became accessible, making this ambitious exhibition possible. They feature surprising early works from the late 50s to 1970 (including a self-portrait made at the age of 16), as well as from his expansive 90s series of ‘Slogan Paintings’ which address the repressive government policies and tabloid hysteria of the AIDS crisis.

To celebrate the opening, IMMA invited writers, artists and activists to pay homage to Jarman’s radical legacy. Here’s what they had to say:

Olivia Laing , writer, novelist and critic

“I grew up in a gay family in the Section 28 era, a moment when the gay family was explicitly being made illicit by the state. But it was also the era that Derek Jarman’s films were being played on television. There was a feeling in the work that he’d created a collaborative world, a way of art making that involved many people rather than the individual heroic artist. You’d think that the artist is always doing that: creating a communal, collective dream world that we can all inhabit, but it’s something rare. An artist who can do that is incredibly inspiring to other artists. Walking around the show and seeing how strong the paintings and elements of Derek’s work are, it’s almost like he’s rising to our vision now. This always happens to artists — it takes almost a generation to see who they were and what they were doing.”

Peter Tatchell , human rights campaigner

“Derek Jarman was the first public figure in this country to come out as HIV positive. And that took incredible courage in the toxic, homophobic atmosphere of that era. Derek wanted to transform society for the benefit of everyone: queer and heterosexual. He wanted to change society, not merely get equal rights within it. He had a very skeptical view towards straight serving laws and institutions such as the police, the church, the armed forces. He never wanted any honours or state recognition. He didn’t require approval. And I think we see that not just in his direct activism for LGBT+ rights and the rights of people with HIV, but all throughout his artistic endeavour as well. He was a great English radical.”

Jon Savage, writer, broadcaster and author

“I actually knew Derek well for the last thirteen years of his life. Derek was a very important figure, certainly in London, to the resistance against Margaret Thatcher and the new right regime and the start of all this horror that we have now. Derek is still very contemporary and it’s really great that we have these exhibitions highlighting his work. In a way, I think he’s found his time.”

Seán Kissane, curator of Derek Jarman, PROTEST! at IMMA

“There is that theory that to be a white English man means that you have no identity, you are invisible. For me, I see Jarman as queering Englishness, and queering that white heterosexual identity, because he’s constantly picking at it and making it bleed.”

Charlie Porter, writer

“My mum and dad were at the Slade with Derek. I had a black and white TV in my bedroom and they encouraged me to watch Jubilee on Channel 4. I was very young, about ten or so. I stayed up until midnight and watched this film and it was my first window onto queer life. Derek was everything that century didn’t want. There wasn’t a place in English culture for someone doing more than one thing and going between them.”

Elisabeth Lebovici, art historian and critic, author of Ce que le sida m’a fait (les presses du réel, 2017)

“Something that I see in this Derek Jarman exhibition is the way he imposes some material effect not only to the object represented, but also to the material of representation itself. I’m thinking about how in his painting — and maybe film, photography and also architecture and scenography — there is something that is attacking pure visuality, pure vision. Something, in religious words, that is going from incarnation to incorporation. And I think it is really important to notice that in his way of working. I was really interested in the queer series of paintings and how Jarman attacks the support with something that has to do with rage.”

Tonie Walsh , civil rights activist, independent curator of Irish Queer Archive

“Derek’s early filmography was part of my coming of age as an activist and as a gay man. It was really crucial for me in developing a positive sense of self identity. He has so much to say about the ways in which we remember. Particularly the place of memory in adjusting to the AIDS crisis. I think we’re at a healthy remove now where we really need to try and make some sense of that dreadful period, learn from it and apply that memory to the place we find ourselves in today. Derek has this utter lack of sentimentality, around how he expresses himself as a radical queer man. He embraced notions of intersectionality before people had even given it a name.”

Richard Porter , artist and publisher at Pilot Press

“Growing up in the post-AIDS era, it dawned on me that a lot of people I was idolising were dead, and there was no one I could go to for mentoring. Derek and his work inspired me to try and emulate those things through collaboration. He was kind of a light that inspired me to do it.”

(Quotes were extracted from a one-day seminar and edited for readability).