Louise Lyngh Bjerregaard is not only a designer and artist, but also somewhat of a textile whisperer, if you will. “I’m very obsessed with materials,” she tells me, on the phone from her home in Copenhagen. “I think that they all want something and the life they have is not necessarily the life they want to have. I try to listen to the material, to see what it wants, in a way.”

The multi-disciplinary creative has harboured a deep fascination with the lives of fabrics since childhood. Growing up as the youngest sibling in a family without the disposable income to spend on new clothes, Louise was often the recipient of her older brother’s hand-me-downs. “It was a struggle growing up as a girl wearing oversized boy’s clothing,” she recalls. “It was something I was teased about in school.” Resourceful, even at a young age, the designer quickly found a way to make the pieces work for her, either through inventive styling or by cutting them up. “I was trying to make the clothing something it was not, originally. It was a way to take ownership of what I had and a way to create my own identity with it,” she explains. “I think that was one of the turning points for me in terms of what fashion can do for you: how you can communicate yourself through clothing.” The designer has gone on to translate this lifelong love of fabrics and garments — and this inherent craftiness — into a career that has spanned not only fashion, but the realms of visual art, performance and more.

Louise studied fashion knitwear at the Scandinavian Academy of Fashion Design and then at Central Saint Martins in London. But it was during a stint interning with New York-based label Eckhaus Latta that she really discovered her preternatural expertise in textiles. “When I see a fabric, I already know what it wants to be. I see how it can be brought to another life,” she says, of her textile selection process. “That’s what I’m good at. That’s what I did for Eckhaus Latta and I know that’s what [they] saw; they said, ‘You can see a textile’s purpose.’”

Since relocating to her native Copenhagen, Louise has brought this intuitive design sensibility to her namesake knitwear label. And her atelier is set up to encourage an exploratory process — with textiles always at the heart. The studio is divided into two sections, one devoted to non-electrical machine knitting and one to hand-knitting, with a huge tower of yarn — “you know the towers of cans in supermarkets?” — on display in the center. “This is where our process starts: the fact that we’re always exposed to the yarns and materials. Because then we’re constantly dreaming and thinking,” she says.

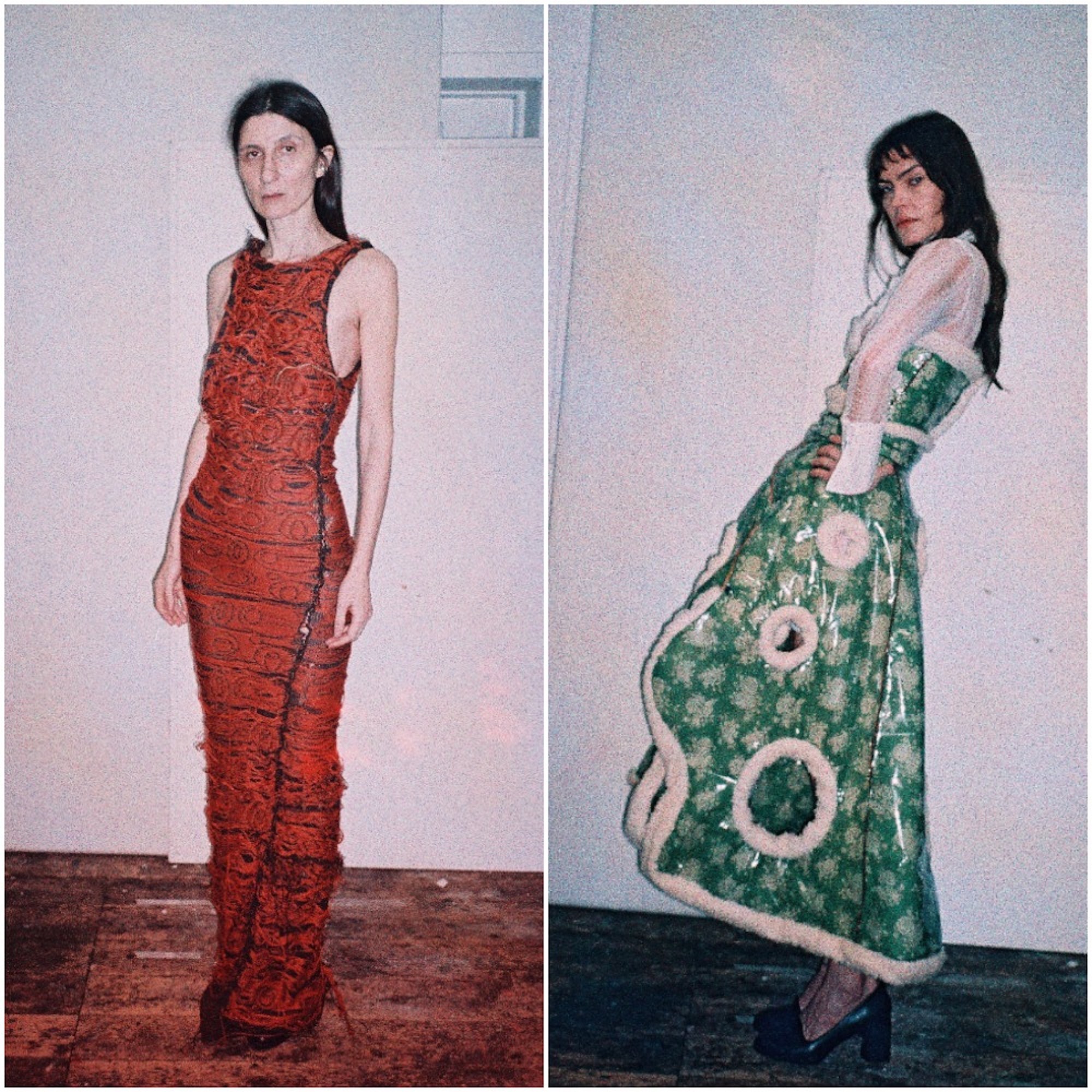

Around 70 percent of the label’s textiles are deadstock — some sourced on the go or stumbled upon, by chance, from various hole in the wall shops and international markets, some are hand-me-downs from other designers or factories. An undulous green skirt set — the showpiece of the label’s autumn/winter 20 collection — is crafted from a tablecloth found at a New York City hardware store. Pieces from previous collections are sometimes cut up and remade into new-season garments. A leather ballgown was painstakingly assembled over a month and a half period from tiny scraps that would have otherwise ended up in the studio bin. “We’re constantly trying to use what we already have,” Louise explains. “I think that’s the good thing about being a young brand who’s not financially secure in any way, if you decide to work with it and not against it. It’s about learning how to adapt to your situation, to make the best of what you have, and to not limit yourself.”

Louise describes her studio’s design process as “a conversation about trying the impossible” with the goal of “creating our own language within knitwear.” Louise and her team are constantly trying to push conventional boundaries, and break down sometimes physical barriers in order to create things that have never been made before. She describes how this process takes shape in the real: “Trying to use a thick bouclé on a knitting machine is such a struggle. But then it’s kind of a competition, in a way, to find how it can be used and how we can work our way around this.”

Experimentation also comes about in outré color pairings, unusual textures and mix-and-match yarn combinations: “It’s a very considered approach to working with colors and materials, considering what types of different materials work together. I work in a way that combines traditional textiles with non-traditional textiles. We have a sequin yarn that works well with a fine wool bouclé, but in traditional knit you would never do that.” Louise’s green tablecloth dress is trimmed in this same creamy bouclé. It’s an oddball combination that, somehow, works.

Although Louise and her team don’t design in seasonal collections — forgoing the fashion calendar’s frenetic pace for a more fluid creative process — they presented their newest collection in Paris to coincide with the AW20 shows. Creating a full collection — a first for the team — proved a challenge, albeit a “fun” one. It was a matter of stretching the designer’s uncompromising approach to knitwear across an entire range of garments to create a cohesive entity. The collection also served as a turning point, or, perhaps, a point of reflection for the interdisciplinary artist. “I initially thought that making textiles as art pieces would be the direction that would set me free, in a way,” Louise says. “But with this collection, I experienced that it’s the other way around, that I’m more free creating clothing.”

The showroom for the label’s new collection, which was conceived in collaboration with musician Astrid Sonne, as half-performance art piece and half-fashion show, is a typical representation of Louise’s artistic oeuvre. “I wanted to have Astrid performing in the showroom without it being centered around specific garments. So, what we did (and I hope I’m not going to get in trouble for this),” she laughs before continuing, “is we bought a lawn in Paris — fifty square meters of real grass — and covered the floor of this beautiful Parisian apartment in it. And then with set designer Isabella Killoran, we turned all the clothing into furniture so people could interact with the garments in a different way. It was kind of nerve-wracking, but nothing broke, luckily.”

Louise’s artwork center around textiles; both her design work and her art exist together, in a middle ground between the two disciplines, frequently exhibiting a palpable push-and-pull, her clothing never wanting to fully cross over into the realm of ‘fashion’, and vice versa. “I do consider myself both an artist and a fashion designer; that interdisciplinary field is where I thrive,” she says.

For her most recent art installation, “All That Matters and Then Some”, Louise and her team moved their entire atelier – “everything: all the furniture, all the boxes with all the labels, all the clothing, all the machines, all processes for dyeing textiles, just literally everything” – from Copenhagen to Wood Wood’s retail space in London. The live installation featured two members of the studio team and Louise, herself, working around the clock, seven days a week, for a month last December. “We wanted to show our universe to [Wood Wood’s] customers,” Louise says of the concept behind the piece. “I wanted to create an intimate space for people to see the process behind making these garments, behind running an atelier, especially in these consumerist times. When you have a label, everything is so closed off. I wanted to remove that distance and create another way of seeing our industry.” Visitors to Wood Wood could see Louise Lyngh Bjerregaard’s finished garments hanging, price tag and all, on the store’s racks, and then wander downstairs, to the atelier-installation, to see how those final pieces came together: “the beginnings, me draping, the final touches and some of the girls taking naps in the corner,” she laughs.

Louise and the team decided, very strictly, not to interact with any of the viewers — “I wanted them to be able to snoop as much as they wanted without feeling they were in the way.” Instead, she set up one of her knitting machines for visitors to try out the processes they were seeing, for themselves. “I wanted people to experience the anxiety of trying something new, which they would obviously not be good at. But then immediately, when they started knitting, they would feel a sense of joy and commitment and ease,” she explains. The experiment resulted in a large knitted textile piece, marked by many cuts and errors, either due to the machine jamming or the knitter losing track of their yarns. “It became more of a symbol of being together despite errors. And it ended up being very beautiful and personal. That feeling of community is something that I really like,” she says. “We have the piece in our atelier.”

When asked whether knitting is as much an emotional process for her as it was for the beginner knitters at Wood Wood, she answers, emphatically, “Definitely. It hits all the emotional aspects that I have as a human being. It helps me when I experience anxiety or when I’m not feeling well, or even when I’m feeling very happy. Because I’ve experienced what it can do for me, I want to pass that on to other people. If at least one person experiences what I can experience working with textiles and knitting, then I think it’s a worthwhile accomplishment.”