In Untitled, Ludovica de Santis journeys around the Latium countryside near Rome to understand why the town she used to live in seems to be stuck in limbo and stagnation. She dives into the reason the locals decided to stay or couldn’t move out and explores the seemingly infertile landscapes around the neighbourhoods. Her visual research is based on the concept of ‘geographical psychology’ or ‘spatial psychology’ rooted in psychogeography by Guy Debord. It is defined as “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotion and behaviour of individuals.” Informed by this theory, Ludovica returns to her hometown and captures the residents and Italian countryside in their constant monotonicity, social isolation, and existential loneliness.

Ludovica grew up in the small town of Civita Castellana, near the city of Viterbo, but moved to Rome at 14 for high school. After finishing, she stayed in Paris for a few years before moving to Milan, where she’s now based. It’s been two decades since the last time she lived in her hometown. When she returned to visit her family, Ludovica was struck by how the Latium countryside had stayed the same. “Over the years, I’ve seen the silence, the involution, and the inactivity of it all,” she says. “People still suffer from boredom and become estranged from social gatherings. They confine themselves to a life with very few social interactions. Estrangement becomes the norm, and closing oneself off is the response to curiosity, with no genuine daily interaction. In some rural or provincial areas where residents live farther from each other, the lack of public spaces, neglected resources, road conditions, and varying weather conditions can even make matters worse.”

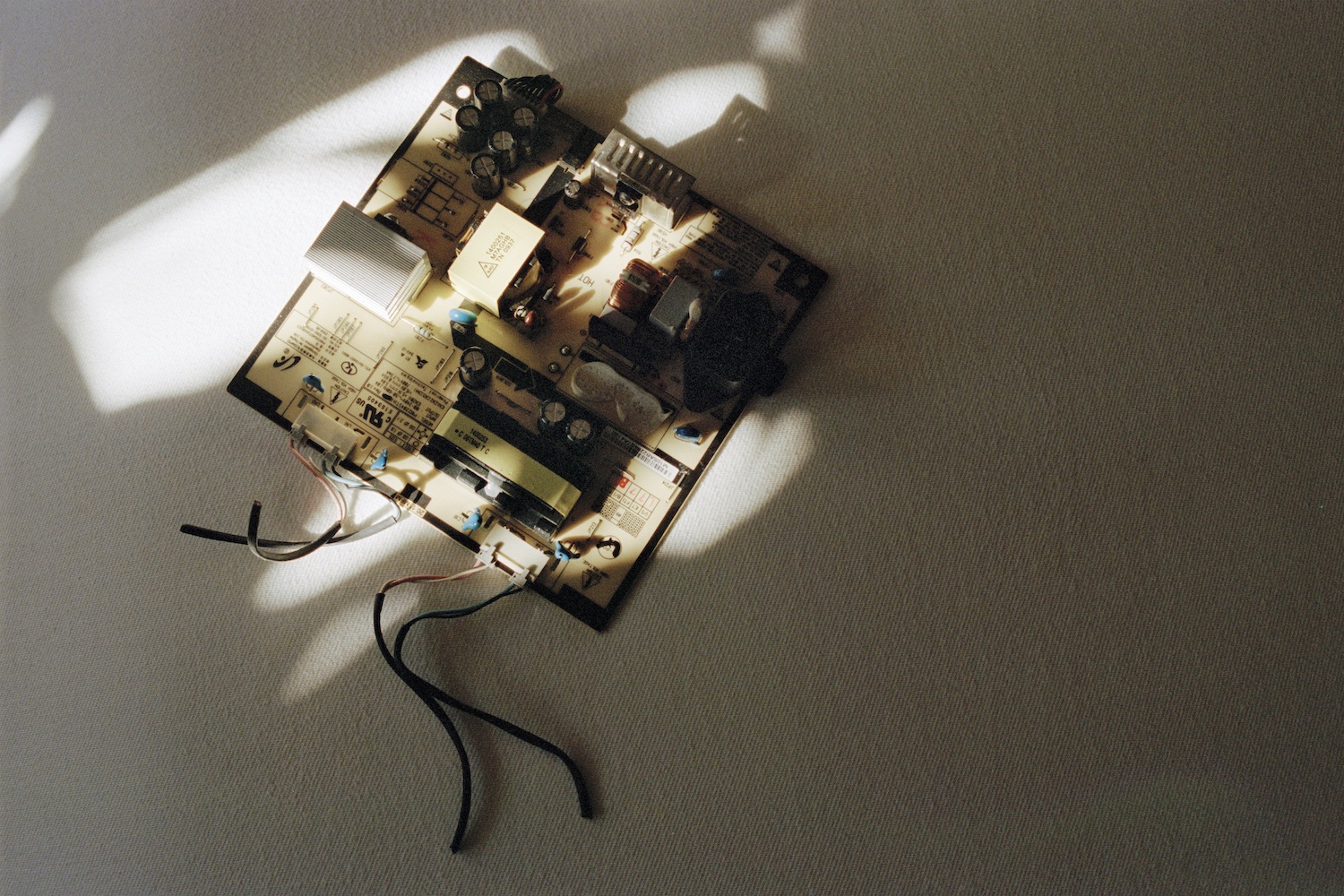

There’s more to stagnation than meets the eyes in Ludovica’s photos. The barren landscape makes the Latium countryside look like a desert. Tall wilted grasses keep growing, and the remaining cement buildings are solely fading. A ditched flat tire was left forgotten on the main road. A dead fox was found on the highway and its lifeless body stayed there for weeks. An abandoned room is thrashed, the former owners leaving all their belongings and furniture inside to rot. The few cars that make an appearance only do so to use the countryside as an detour to cities like Rome and Florence. Yet for the residents, the familiar eerie silence and inactivity reflect an innate state of being, one they’ve built their lives on.

“People stay because the province, in a way, traps you,” Ludovica says. “If you grow up there, it’s hard to leave. The cost of living is lower, everything is more human-sized, and people can live at a much slower pace compared to the city. In the province, there is little confrontation, and the monotony of certain habits makes people feel safer.” The silence and isolation in the city make it a safe space for the residents, away from the petty crimes and confrontations often infesting big cities. Yet the tight-knit community might mean everyone knows everyone, and everybody knows everything. Privacy and secrecy meld, and sometimes, it creates a potent brew for friction.

Take ‘1’, for example, where the man, frail and grief-stricken, sits alone at the dining table, bathed in sunlight and lost in his thoughts. His story, as Ludovica narrates, is as sombre as he looks. “He lost his lover last year,” she says. “Now he lives alone in his house in the Central Italian countryside. He smokes two packs of cigarettes a day. He’s depressed. He’s alone. He should undergo psychotherapy, but in this city, it is difficult to find that kind of drive to analyse oneself. He lacks that self-analytical approach to things, and he doesn’t know anyone who can guide him in such a choice. His family stopped talking to him for a long time due to his homosexuality, and after his partner’s death, he doesn’t have many people left to engage with,” she says.

Untitled focuses on life in Italian suburbs such as this one, reporting a motionless state where almost nothing has changed in decades. “With my images, I want to show the stagnation experienced in small towns, the constant sense of abandonment, the alienation from reality, as well as the loneliness that annihilates any form of growth, progress, community, or human openness,” Ludovica says. “My attempt is not to criticise the countryside or provinces but to provide a profound analysis of how the geographical and urban structure impacts the social reality and psychological dimension of individuals. The countryside may be a barren land, but it is the flowers that bloom in hostile terrains that are the most beautiful, rare, and precious.”

Credits

Photography Ludovica de Santis