Sara Berman and Luella Bartley’s show, Armoured at Kristin Hjellegjerde, is framed by a poem. Co-written by fashion curator Judith Clark and psychoanalyst Adam Phillips, it lists the contradictions and mysteries of the clothed body. “1. Keeping a dark or secret profile,” it opens. “2. Hardened for the elements; soft-centred.” Perhaps the most fitting point though is number 5. “Sustaining belief in the inside and the outside/ the invulnerable space and the essentially unprotected body.”

Sara and Luella’s show is full of contrasts and antitheses. Hard/ soft. Inside/ outside. Clothed/ naked. Powerful/ unprotected. The two women, who have been friends for years, didn’t know exactly what it was that they were embarking on when they first agreed to a joint project — but they knew that there was something important to uncover.

“We made this pact early on to be incredibly honest about everything,” Luella says. “It was weird, because we would meet and we’d have these long walks, and we didn’t necessarily talk about the work… but that was the underlying thing.” They walked, they talked, and then they went away and embarked on frenzied periods of making. “There was quite a bit of commonality around where we find ourselves, within our bodies, at this stage in our lives,” Sara adds. “We both coded [that] from different points of view. Luella really focused on the line. I focused on the mark. And we ended up with a body of work that feels like a conversation.”

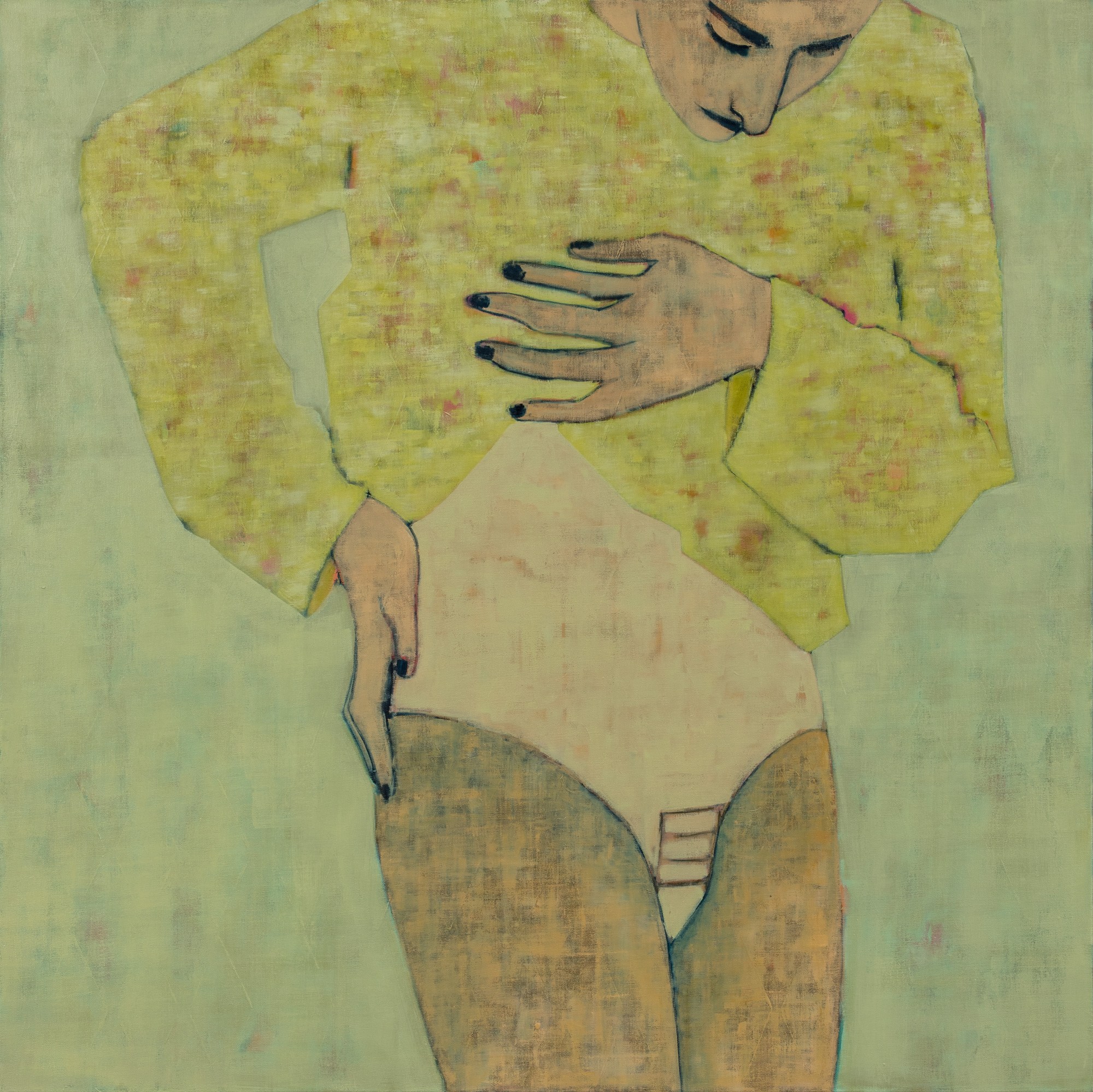

In the gallery, this conversation plays out between white walls. Luella’s lines are jagged. Across paintings and clay and plaster sculptures, she captures what she describes as “these big, bold, sort of beautiful, grotesque bodies.” With their contorted limbs and exaggerated features, the paintings hold echoes of Egon Schiele and Jean Cocteau. Many shield their faces, anonymous and somehow in a state of flux. The images, Luella says, are somewhat inexplicable, but came from “a need to expose and be very raw.”

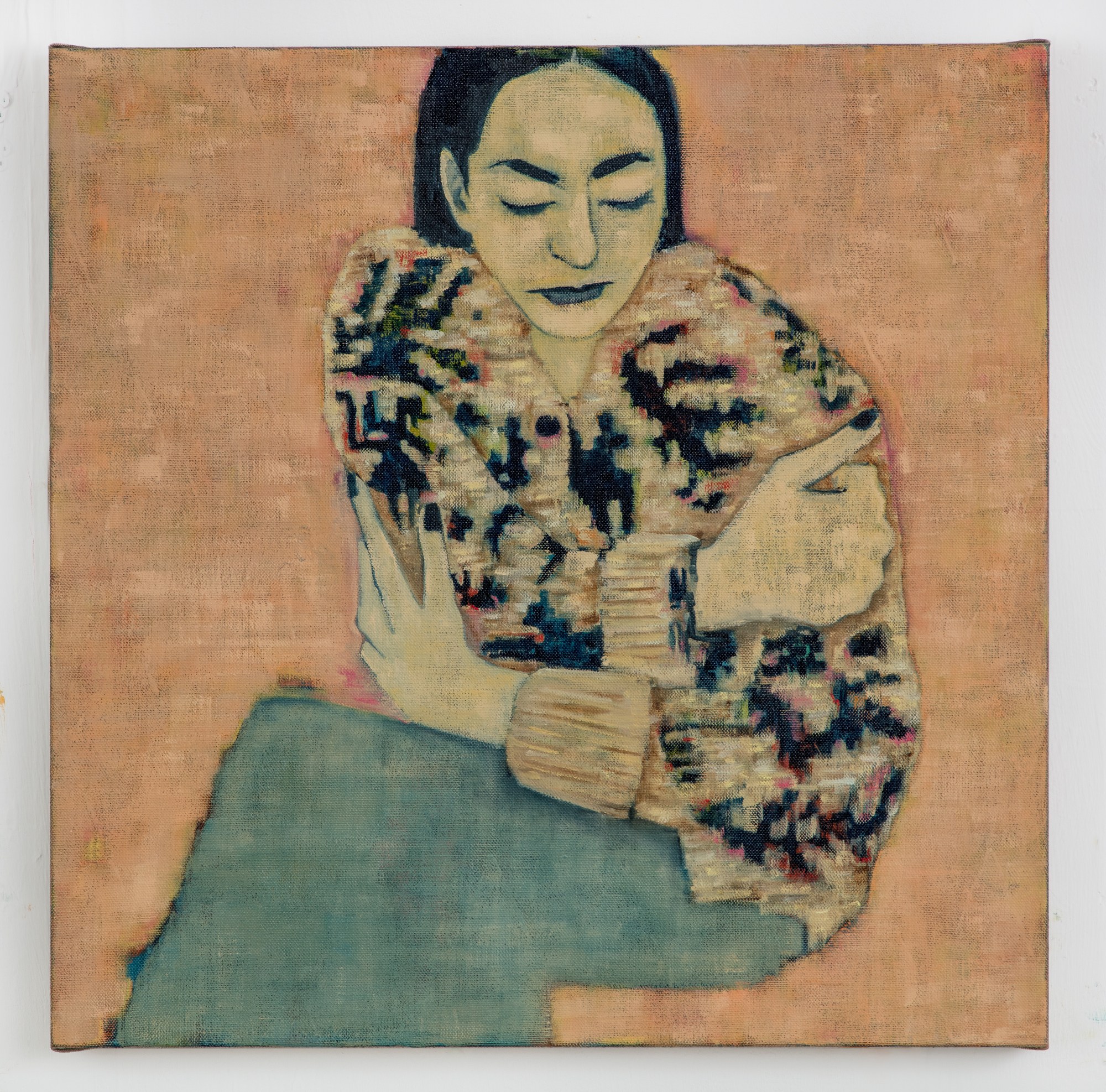

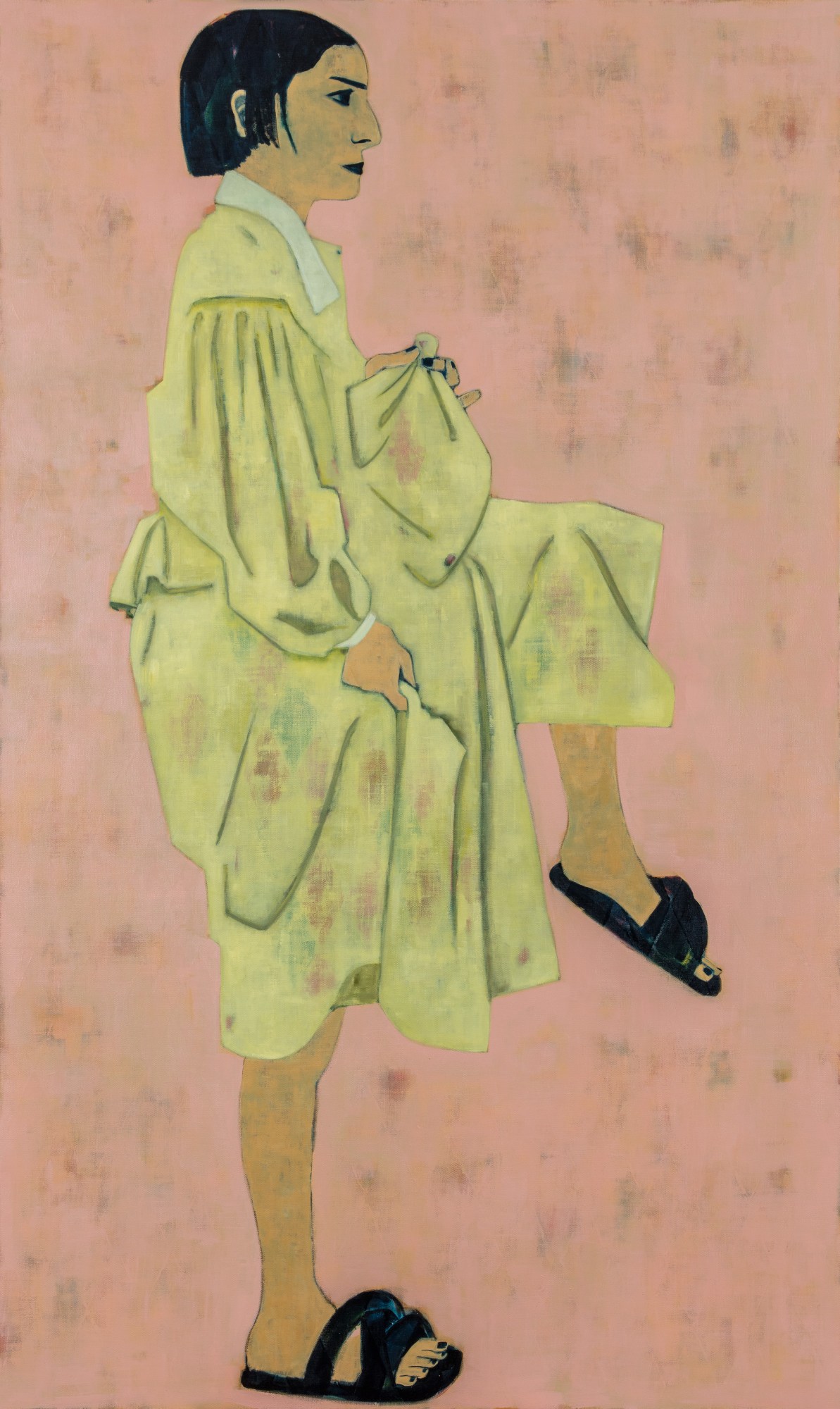

By contrast, Sara’s works all centre on the same dark-eyed, dark-haired woman, who bears a striking resemblance to her. Across several vast portraits — some stretching nearly floor to ceiling — the woman’s mood shifts: sometimes pensive, sometimes sullen. Her clothes do too. She wears cowboy boots and thick-knitted cardigans. In one, she sports a buckled coat that looks rather dashing until you find out that it’s a deconstructed straitjacket. Squint at them sideways, and you’ll start to see other layers lurking beneath the fabrics: a harlequin pattern struggling to make it to the surface. “The work is based on the tradition of the harlequin: Arlecchino being the trickster-joker of the commedia dell’arte,” Sara says. “But as a woman the trope is the trickster whore.”

Sara describes this harlequin diamond print as “the soul of the painting from which all the work is built.” To her, it’s the perfect vehicle for her preoccupation with the silencing of women: a background that is painted over but can’t quite be escaped. “I spend my time obliterating that persona, that tricky woman, that voice of a harpy, but her voice comes through in the colours and the patterns,” she says. “No matter what you do to subdue it, it will still come through.” The process of stripping back the layers can be incredibly forceful, involving hours scraping and peeling. “I love the fact that the soft palette belies the violence of making them,” Sara says, smiling.

For Sara, it took a while to become comfortable with painting clothes. For both artists, in fact, this is a new creative chapter, each having previously helmed a successful fashion label under their own name. “I was lucky enough to get the end of an amazing period: to be working in fashion in the 90s, at Central Saint Martins in the 90s,” Sara says. “It allowed me to develop into the type of artist that I am. I’m really proud of it, and proud of owning a business.” Although this background doesn’t directly inform the dialogue between the two artists, she sees it as a point of shared affinity. Having grown up in the same culture and navigated some of the same challenges, there’s a deep mutual understanding.

Clothing — or its lack thereof — is an enormously present part of Armoured. For Luella, doing away with clothes was a means of reconnecting with what felt real. “This is quite an autonomous [approach to the] body,” she says. “When you’re working in fashion, you’re always thinking about the idea of femininity and sexuality… You’re dressing a woman.” She saw fashion as something driven by narrative: her irreverent designs offering the chance to play with or subvert expectation. Nevertheless, she says, it was still “an image, a mask… [you could] hide behind. This feels very exposed. I had to rip everything apart.”

By contrast, for Sara it’s been a process of rediscovering the symbolic power of those outer layers. After closing her label in 2012 and subsequently completing an MA at the Slade, she largely painted nudes — a strategy she now characterises as “avoidance”. It was only after she alighted on the harlequin figure that she felt comfortable re-engaging with what her subjects wore. “[Now] I work with textiles a lot, she says, nodding at one of the portraits clad in a cream smock and black sandals. “But it’s less about fashion and more about what clothes do. How do we operate within them?” She would never paint a stiletto, she adds. “I hope nothing about it feels fragile.”

The final point in the poem Armoured is a simple one. “7. Undressing revised.” One senses here a supple, and very personal, set of revisions: ones that not only dress or undress the human form, but redress it too. In these layers and processes of unpeeling, these heavy fabrics and light suggestions of motion, there is a sense of something being imagined afresh — a conversation begun, but not necessarily ended.

‘Armoured’ is on at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery until 11 June.

Credits

All artwork courtesy Luella Bartley and Sara Berman