Photographer and recent graduate from Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, Maisy Lewis shares an excerpt from her personal photo project and accompanying diary, documenting a surreal and evolving collaboration with a Catskills groundskeeper named Shawn. What began as a thesis project became an intimate exploration of fantasy, trust, and forgotten places.

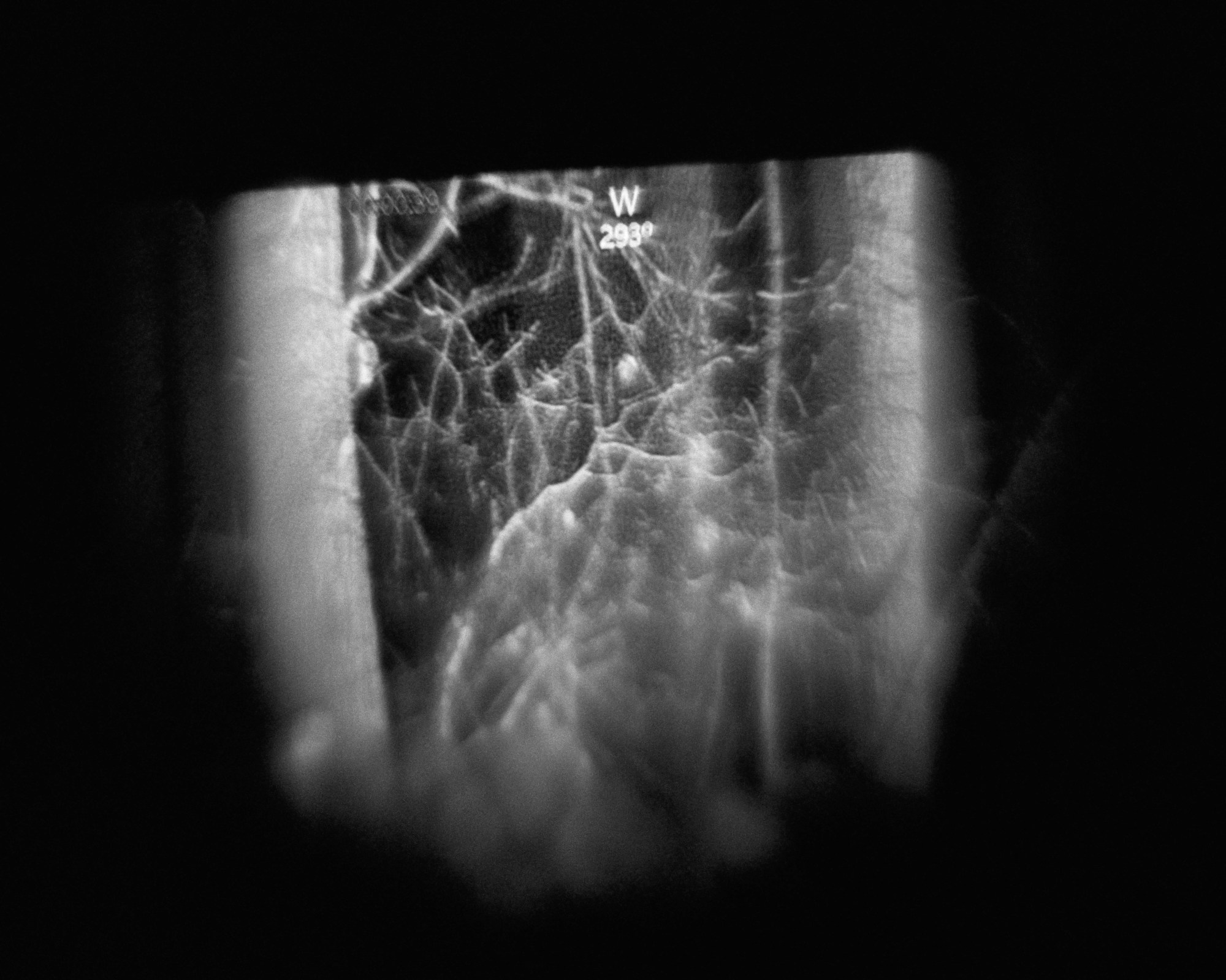

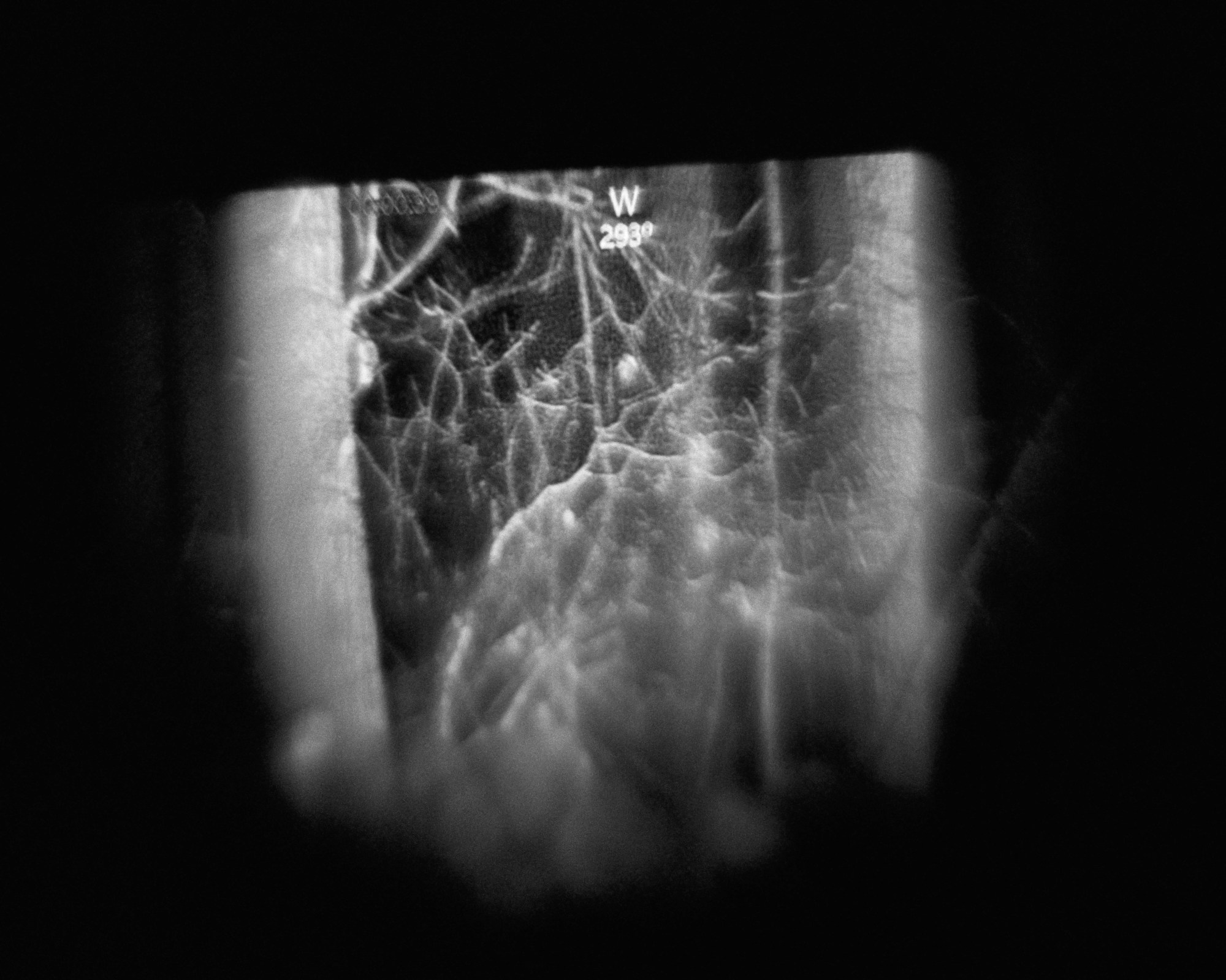

It’s January in upstate New York, and I’m standing in a pitch-black Catskills forest at 11 p.m. Snow covers the ground. I can’t see more than two feet in front of me, and my only companion is a 54-year-old man in a ghillie suit, carrying a rifle. In contrast, I’m 23, a woman on the cusp of graduating college, bundled in my dad’s oversized puffer jacket and holding an old Pentax 6×7 medium-format film camera.

I’ve lost track of time and can’t tell if one day has ended and the next has begun. My phone buzzes. It’s my twin sister FaceTiming to say hi. I put my camera down and lift my phone to show her the scene: a group of bare trees illuminated by photography lights on tall C-stands. My tripod leans crookedly on a pile of snow next to two boxes of 120mm film. My camera hangs from my neck. Shawn—the man in the ghillie suit and my subject—grins at my sister through the netting. She looks terrified. “I’m busy with a shoot,” I say. “I’ll call you later.” She hesitates, then asks if I’ll check in when I get home safe. Of course I will.

January marks my fourth month photographing Shawn. We met while I was location-scouting for another photographer I’d worked with throughout college. I was deep into my photography thesis for my undergraduate degree in studio art. With a looming critique on Monday, I needed something new to show my advisor.

For the past three years, I’d explored feminine identity through photography, creating bright, pastel portraits of women, bedrooms, and hair dye. These images helped me navigate my place in the world. But by my senior year, the work had become predictable. I felt stuck. For my thesis, I wanted something different—something strange, maybe even uncomfortable.

When I got a call about an abandoned zoo, I drove three hours from my university in Connecticut to the Old Catskill Game Farm, a derelict private zoo tucked into the woods of upstate New York. Shawn, the groundskeeper, greeted me at the gate in an old golf cart, holding a long staff, with a herd of goats trotting behind him. He was tall, much older than me, and a man—three things that set off alarm bells in my head, especially alone in the wilderness.

My photographer friend was running late but on her way, so I (cautiously) accepted his offer of a tour. He led me down half-paved roads into crumbling buildings and winding forest paths. As we walked, he asked about my family and guessed I was Swedish—maybe because of my blonde hair. “I’m Estonian,” I said. “Then we’re both Baltic Sea vikings,” he replied. That afternoon, we bonded over family history, mythology, and our shared love of The Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones. Maybe my braids reminded him of Daenerys Targaryen, or the camera in my hands looked like Legolas’s bow. Whatever it was, he seemed to take a liking to me. By the end of the tour, I no longer felt unsafe. Shawn was eccentric, sure, but generous, kind, and eager to share his strange affection for the decaying zoo he helped maintain.

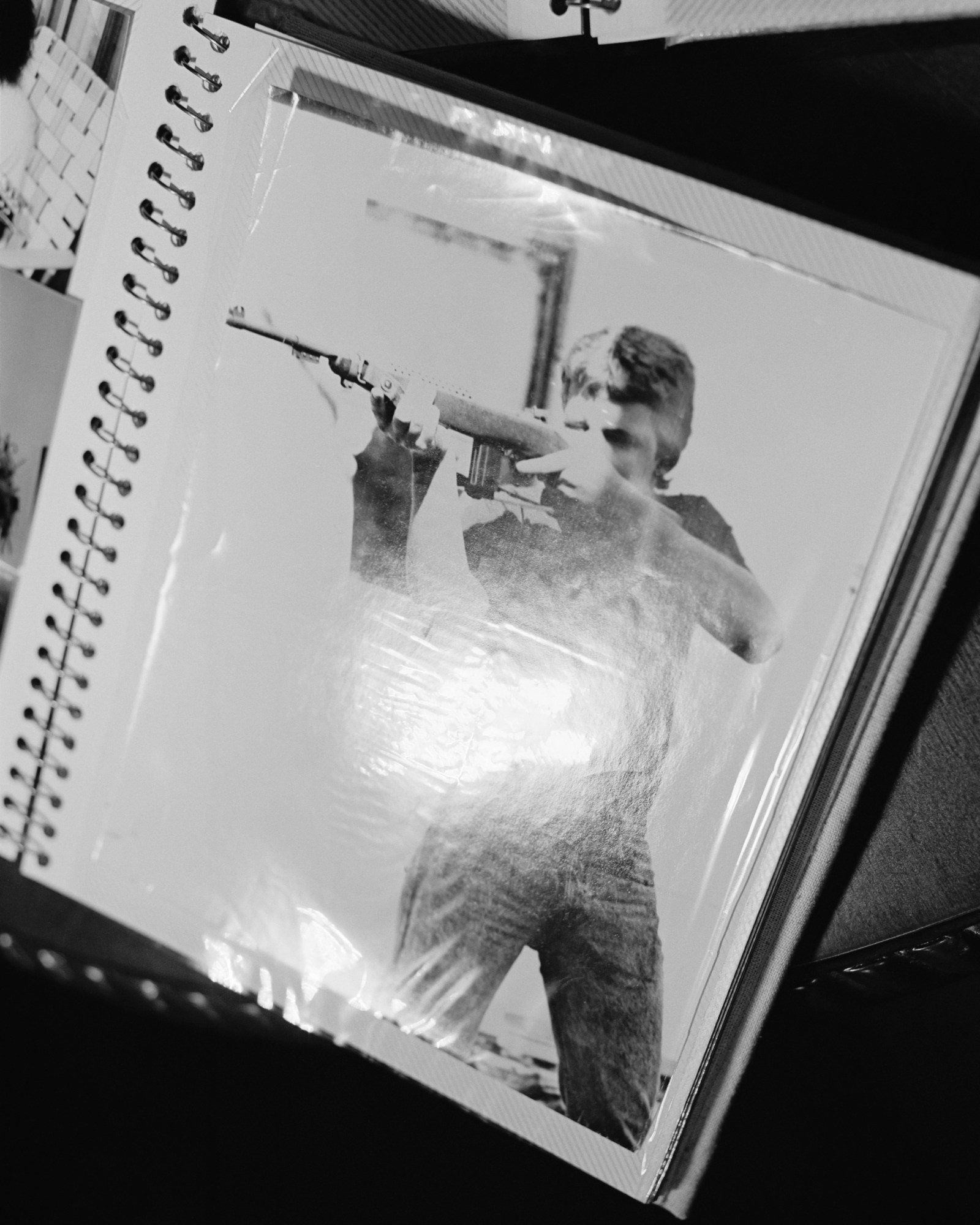

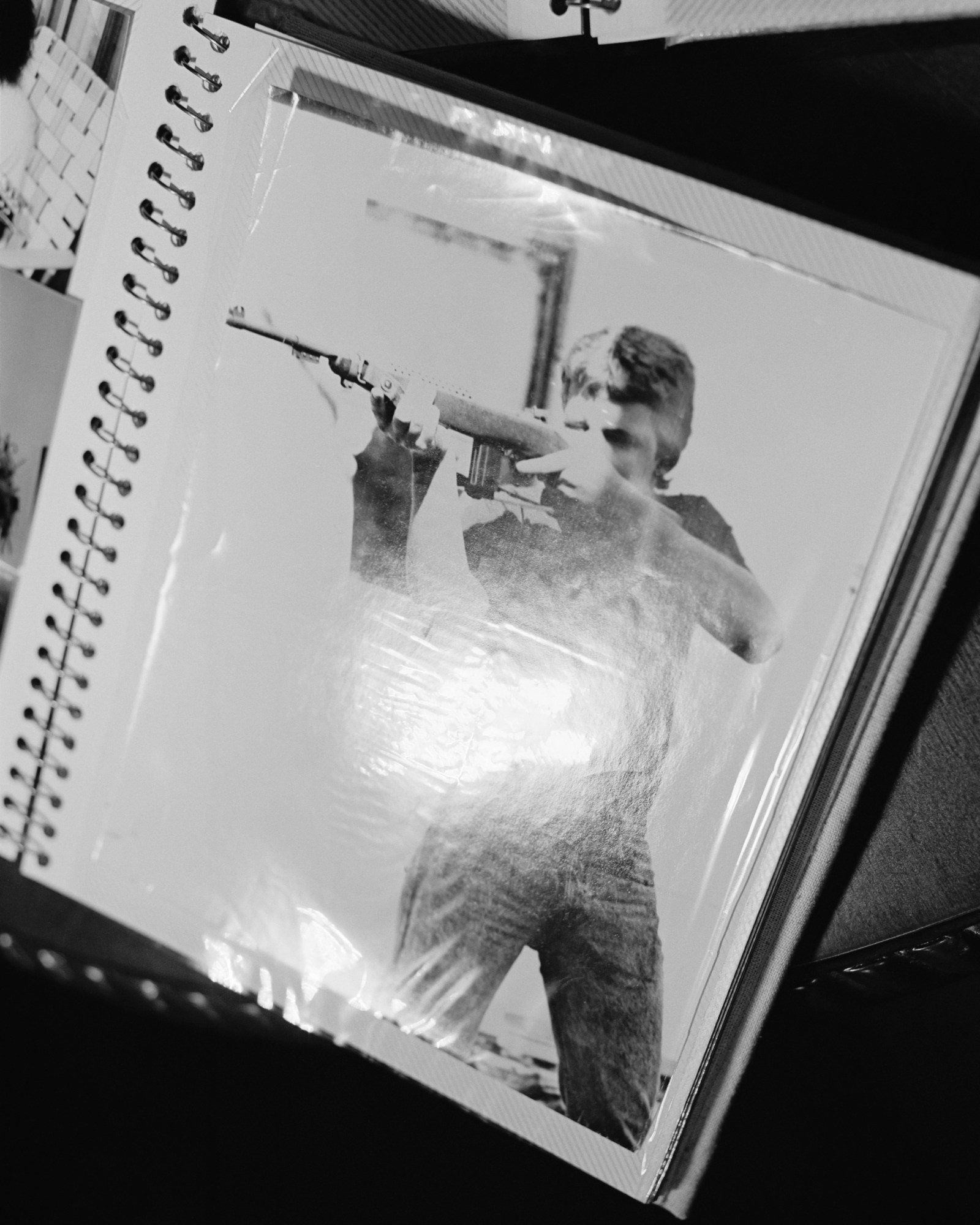

In the months that followed, he introduced me to his six goats, who followed him like puppies. He showed me his collection of guns, knives, handmade dioramas, and action figures. He told me stories—some possibly real, others clearly imagined—about fighting the Ku Klux Klan as a teenager or doing undercover work for the Navy. His cigars left every room steeped in a sickly sweet haze. Dragon tattoos peeked out from beneath his t-shirt, permanently branding him with fantasy. I kept my camera close, always loaded with a fresh roll of film, my finger near the shutter. I wanted to dig deeper into his world.

As our relationship evolved, my images began to reflect the strange space I occupied in his life. He started calling me his little sister. He nicknamed me “Maisy Star,” after our shared favorite singer, Mazzy Star. When I asked if I could photograph his dragon tattoos, he stripped off his shirt and knelt in front of me without hesitation. I realized then that he trusted me.

Our relationship—and our art-making—had become an exchange of personal vulnerability. With no partner, no children, and no close family, my images became portals into a life otherwise unseen. Each photo was an intention we set together, a moment that disappeared until I uncovered it again in the darkroom. There, we became something else—both artist and art object.

When my sisters and I were kids, we built fairy houses in the backyard and played mermaids in the ocean. Shawn’s forgotten zoo felt like a grown-up version of that, a crumbling stage for his juvenile fantasies, where he could play with guns and imagine himself as the lone hero of a dilapidated fairy tale. Shawn is both a full battalion and a solitary soldier. I direct him as both a witness and a participant in his fantasy world. He is a divine shepherd and a lethal sniper, a hero and a perpetrator, a builder and dissector of delusion. He is a full cast and a one-man show. This is his psychological theater, where fantasy and reality, dream and nightmare, coexist.

Shawn revives legacies of spaces left behind. By photographing his world, I continue that cycle—immortalizing a life that might otherwise be forgotten. These images are two-way dreams: our shared language, a layered reality of dragons, goats, and land lost to time.