“I tried to make paintings of pubic hair so gorgeous you can put them over your couch,” says American artist Marilyn Minter, who has dedicated her life to breaking taboos and ending shame around sex and desire. “Throughout art history, there are only a handful of paintings with public hair and big dicks because they decided these things were too vulgar. They couldn’t tolerate it. Just having breasts was like hardcore porn in those days. Victorians would faint at the sight of an ankle. I just want to give people permission to look at porn, get pleasure out of it and create images for their own pleasure.”

As a pro-sex feminist throughout her five-decade career, Marilyn has been at odds with the Right and the Left alike, for porn — and its opponents — has bedfellows on both sides of the political spectrum. Yet, for all the efforts to censor it, Marilyn understands that “porn, like fashion, has always been a major engine of the culture. It’s despised by intellectuals because it’s considered shallow, but it’s so much more important than anything academia could turn up.”

Indeed, sex — in its most essential state — ensures the very survival of the species. In its primal form, art can be used to manifest dreams and desires into reality, making it the perfect tool for sexual expression. Invariably, depictions of sex are as old as art itself, with some of the earliest cave paintings and carved figurines dedicated to fertility rites and idols. The voluptuous curves of the female body were no more exaggerated in prehistoric art than they are today, through cosmetic enhancement procedures that serve similar needs.

Art and porn evolved as one until religious doctrines demonised sex, driving a wedge between the two — elevating one as ‘high’ and denigrating the other as ‘low’. But despite public prohibitions, porn (like sex) continued on behind closed doors, relentlessly moving the culture (like the species) forward. As Patchen Barss chronicles in The Erotic Engine: How Pornography Has Powered Mass Communication, from Gutenberg to Google, books, paintings, photography, film, video, and digital has all evolved as a result of pornographers, who as early adopters, usher in new media by meeting the demands of an unquenchable market for sexual content.

Inherently arbitrary, the line between pornography and art continuously shifts, reflecting the level of tolerance and permissibility of any given place and time. “I know it when I see it,” U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said during the 1964 Jacobellis v. Ohio case, referring to the protection of free speech that extends to everything but hardcore pornography. With the criminalisation of distributing “obscene” materials lasting until the early 1970s, many artists were forced to work underground, lest they face harassment, police raids, persecution, fines, and imprisonment.

In an effort to distinguish art from porn, some have tried to create frameworks using subjective standards of arousal, exploitation, morality, vulgarity, harm, merit, and response. But like Pablo Picasso, who understood that “taste is the enemy of creativeness”, artists have always pushed boundaries with their work, searching for new ways of exploring age-old themes of beauty, desire, love, and lust.

From the very outset, Marilyn has been at the vanguard, developing a new iconography of the female gaze, one that was equal parts seductive, sensual, and subversive. With the publication of her latest book, All Wet (JBE Books), she offers a steamy and sensual look at the classic archetype of the female bather in the new millennium.

Immortalised by artists from Rembrandt to Degas, paintings of women bathers have long maintained voyeuristic overtones, carefully treading the line between art and pornography. By establishing the toilette as part of the art historical repertoire, male artists gave themselves license to intrude upon what is among our most personal rituals of self-care. Adopting the position of a Peeping Tom, an outsider going unseen, the male artist adopts a perspective that inevitably implicates the viewer by extension in a purportedly innocent yet illicit scene.

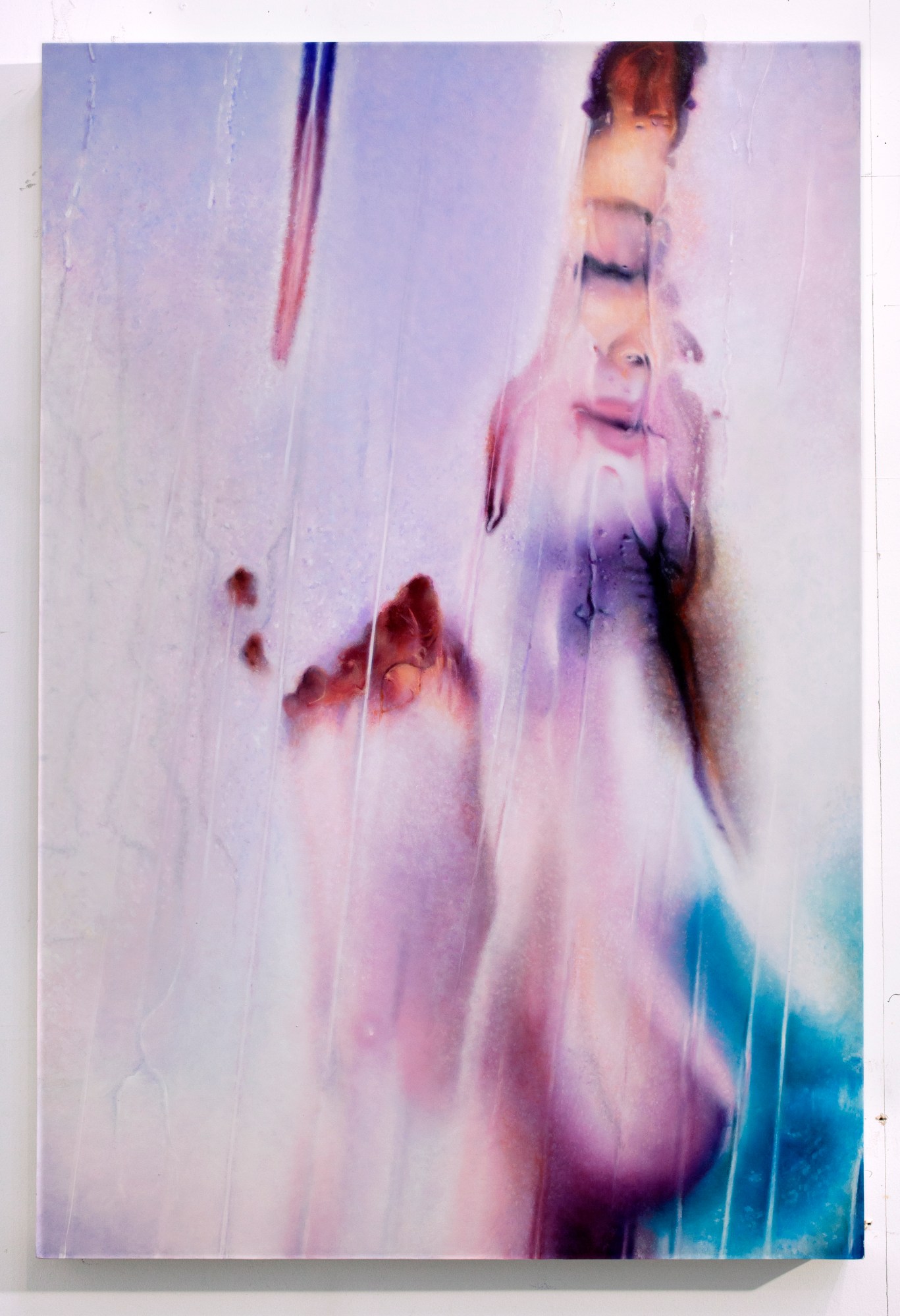

As a woman, Marilyn inherently understands seeing and being seen alike, and maintains that sense of ambiguity in All Wet. Suggestive, rather than explicit, her evocative images of the female body — as seen through diaphanous and translucent layers that obscure, reveal, and entrance — offer a new way of looking, one that understands mystery is an integral part of power itself.

Marilyn draws inspiration from artist Richard Tuttle, who recognised that a great work accounts for both the visible and invisible realms. That ineffable, unknowable, yet profoundly compelling energy that we feel but cannot fully articulate; that is the space that the work of art negotiates. “A painting or a sculpture really exists somewhere between itself, what it is, and what it is not,” Richard said. “And how the artist engineers or manages that is the question.”

For Marilyn, the answer lies in embracing, and thereby erasing, the line between porn and art, adopting a pro-sex stance that was derided as anti-feminist until recent years. From the very beginning, Marilyn remembers just how difficult it was to take a radical position in America. “I hate to say it because it’s really hard to believe, but we were such a small minority in the 1960s,” she says. “When I got to college, most people were fraternity jocks. Maybe one in 25 were feminist. We were on the margins to such an extent it was dangerous.”

By the 1990s, Marilyn watched as the Left and the Right united against porn — just as she was questioning why women artists didn’t engage with these materials in their work. In 1989, she created Porn Grid, a series of four colour-saturated scenes of fellatio, which enraged the virulently anti-porn era of mainstream American feminism. Just as PC culture began to emerge, Marilyn was decidedly unorthodox, adopting a sex-positive approach in her efforts to reclaim porn from the patriarchy.

The Left’s attacks, which Marilyn describes as “very painful”, took their toll. At the time, the Culture Wars were in full swing, and Congress convened hearings to pass the Helms Amendment, restricting the disbursement of government grants to artists who engaged in what they deemed “obscenity” and encouraging of homosexual activity throughout the AIDS crisis. Marilyn remembers, “Anti-sex feminists like Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin had the floor. I was considered a traitor to feminism and dropped by galleries. No one could see Judy Chicago, Carolee Schneemann or me. Then the internet came, and my side won.”

Being on the right side of history takes guts, especially if you get there decades before the mainstream does. “Artists don’t think strategically — they just make whatever that have to, whether people can see it or not,” Marilyn says. “This is what I am compelled to do. It’s like I have no choice.”

With All Wet, Marilyn wanted to see what it looks like to have a woman bathing painted by a woman. “Does it change the meaning? How different does it look if a woman makes images for their own pleasure?” she asks. Casting real women rather than professional models, Marilyn photographs them at length, creating a collage with at least 20 different Photoshop layers. Once the image is complete, she paints the scene in enamel on metal, which adds to the deeply luminous, lustrous sheen.

The result is pure pleasure and delight — an image that is as much about the sheer joy of seeing light, colour and shape as it is about the subject of the woman lost in a moment of leisure, relaxation and self-care. With All Wet, Marilyn understands the female gaze is not a fixed concept but a multiplicity of perspectives slowly coming to the fore.

“I’m very curious about everything,” she says. “I let my work tell me what to do.”

Credits

All images © Marilyn Minter