Avery Trufelman is a fashion journalist and host of the Articles of Interest podcast. She is currently working on a book about The Antwerp Six—Ann Demeulemeester, Walter Van Beirendonck, Dirk Bikkembergs, Dries Van Noten, Dirk Van Saene, and Marina Yee—to be released by Simon & Schuster. After the untimely death of Marina Yee on November 1, Trufelman revisited her book research and interviews, writing this ode to Yee’s brilliance and influence on fashion.

A model stepped out on the runway, completely topless. Her long blonde hair was swept up in a tousled bun. Her eyes were rimmed in black kohl, her lips painted red. Although she wore no shirt, her chest was decorated with a fake suntan in the outline of a v-neck shirt, and she covered her breasts with her hands. The one garment she wore were white pants with a raw, unfinished hem. Below that hem were boots with a split toe, like she had hooves for feet. This was the world’s very first impression of Martin Margiela, at his premiere fashion show on October 23rd, 1988.

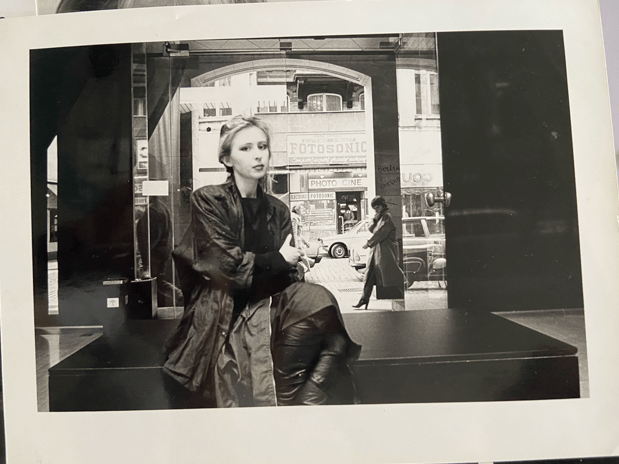

But this is not about Martin Margiela. This is about a woman who was there in the crowd, watching that show. Someone who looked eerily similar to that topless model. Her long blond hair was swept up in a tousled bun, and her eyes were rimmed with black kohl. A friend leaned over and whispered exactly what she was thinking: “She looks completely like you. It’s like, it’s you.”

A second model came out, also wearing tabi shoes, with another stack of tousled blond hair and kohl-rimmed eyes. It was impossible to ignore. More and more models emerged, looking nonchalant and bohemian, wearing backwards skirts, oversized men’s shirts. The garments looked like they had been picked up in thrift shops or sewn together at the last minute. The women all looked, and dressed like this woman in the audience. Her name was Marina Yee.

Marina Yee was an upcoming fashion designer in her own right, and member of the Antwerp Six. She was also a longtime friend and occasional lover of Martin Margiela. Long before “upcycling” was trendy, Marina was digging clothing out of the trash, finding strange pieces at flea markets, and wearing fabric scraps to the club. “By the age of 30 I hope to be at the top with my own collection,” Marina had once said. And there she was at 30 years old, watching Martin Margiela, her childhood friend rise to the top, with a collection that could have very well been her own. It’s just that Margiela had the savvy and skill to get there first, especially because he worked with a business partner, Jenny Meirens.

“People were constantly talking about my talent, but I was insecure and wanted to do everything on my own.”

marina yee

Marina, a consummate artist, had adamantly refused to work with a business partner. “People were constantly talking about my talent,” Marina said. “But I was insecure and wanted to do everything on my own.” Growth had never been Marina’s goal. But now, Marina knew, if she tried to continue in fashion design, it would look like she was knocking off Margiela. Even Meriens’ daughter, Sophie Pay, admits Marina’s influence: “When you just looked at her, how she looked and how she dressed, and you looked at Martin’s collections, it was quite obvious.” Once Margiela laid claim to this look, Marina had been reduced to a muse.

As she watched the versions of herself parade around the catwalk at Margiela’s premiere, Marina couldn’t stop crying. She collapsed in a friend’s arms. “I think it was the worst moment of my life,” she said. The day that Martin Margiela entered the global stage, Marina Yee left it.

Over the next forty years, Martin Margiela, as well as Marina’s schoolmates Dries Van Noten and Ann Demeulemeester, would become titans of the fashion world, and would retire to much fanfare after selling their successful businesses. As of last year, Marina Yee was still renting a one bedroom apartment in downtown Antwerp, where she lived with her adult son.

But at last, in 2021, just after she turned 60, Marina Yee finally planned her comeback. Marina finally found a trusted business partner in Raf Adriaensens, and had been working on a line of clothing that she was starting to sell on SSENSE and Dover Street Market. “Wow,” I thought, as I admired her beautifully remade secondhand coats, “it’s never too late to start again.”

Until it suddenly was too late. Marina Yee passed away on November 1st of this year at the age of 67, after a battle with pancreatic cancer. We lost a brilliant and singular soul, and all the remembrances of her are entirely too short.

Marina Yee was born in Antwerp, but her family moved to the Belgian Congo when she was one year old. Just before the Congo was declared independent, her family came back to Belgium, where they moved from city to city. Marina’s father, who was mixed race Chinese-Belgian, worked as the director of a successful Belgian chain of department stores called Inno, and as he was promoted within the company, the family moved from location to location throughout Belgium. Throughout her childhood Marina moved at least eleven times.

By nature of all these moves, and because of her father’s tendency to lash out abusively towards her mother, Marina’s panic attacks began when she was nine years old. Friends were not allowed to come into the Yee household, for fear of her father’s outbursts, and Marina, by necessity, became a lone wolf. She never related to other children, and Marina became an odd, dreamy, self-sufficient child, who entertained herself by gathering bouquets of wild flowers, baking cakes, and, eventually, sewing clothes.

Marina’s chic and stylish mother taught her daughter that sewing wasn’t difficult, and Marina made high waisted velvet, skirts that were “a bit gothic.” She’d wear these skirts to school, along with her mother’s vintage boots from Paris, wear circles of dark kohl around her eyes, and carry a wicker basket in lieu of a school bag. Marina’s eclectic style stood out during the hippy dippy ’70s, when everyone else was wearing clogs and Indian prints: Marina wasn’t quite en-vogue, but she wasn’t passé either. Her style was just different and entirely unique. And so perhaps it was natural that, when Marina was 15 years old and her family moved again, this time to the town of Hasselt, Marina gravitated to the only other student who also dressed in his own unique way. A neat, dapper, shy boy named Martin Margiela.

Martin and Marina got along like a house on fire. Marina loved to talk, and Martin loved to listen, so he became her audience and she became his entertainment. They became all but glued at the hip. They rode the bus together, they took all their classes together, and spent all their time outside of school together. Marina told Martin about the music that her older boyfriend turned her on to, like Creedence Clearwater Revival and The Doors: music that seemed eons away from the Top 20 hits everyone else was listening to. Their tastes started to merge, especially in the realms of design and in fashion. “He loved my weird combinations. He thought they were fantastic,” Marina remembered. “And so we had something in common, a shared passion for fashion and clothes.” Martin and Marina would be magnetically drawn to the exact same shirt at a flea market, or both of them would bend down at the same time to pick up an abandoned toy on the street. They became magpies—collectors of inspiration and detritus, which they might hoard and incorporate into their art projects.“Our styles were so close: Martin and I were sister cities,” Marina said. “If he thought something, I would say it and vice versa.”

“I regularly had bouts of jealousy… sometimes wished I had become a sculptor or a photographer, or at least something else, so that I could have cheered wholeheartedly for Martin’s success.””

marina yee

Marina followed Martin to the famous Fine Arts Academy in Antwerp, where a department of Fashion was still being developed. At the entrance exam, Marina met a tall affable lanky boy named Dirk Bikkembergs, who readily admitted that he was entirely unqualified for the fashion school entrance exam, but still really wanted to go to fashion school. As Dirk Bikkembergs recalled, it was just by chance that he “saw a very beautiful girl with long blond hair down to her hips, dressed in a white parka that was billowing with the wind,” Dirk recalled. “I thought: she’s definitely also here for fashion. I followed her and sat next to her. Turns out I couldn’t draw. But she could. She helped me out, literally dictating how and what marks I should make. She dragged me through it.” Marina Yee, a beautiful blond girl in the white parka, helped Dirk Bikkembergs into the fashion program, they would meet fellow students Ann Demeulemeester, Walter Van Beirendonck, Dries Van Noten, and Dirk Van Saene, and together they would work hard and party harder.

When she was getting ready to go out, Marina would smoke a joint and throw together an experimental outfit by “creating in the moment” with a single pin or a cinch of a belt, or by quickly sewing a piece of elastic into a swath of fabric. Marina could turn old second hand clothes or a simple scrap of fabric into a show stopping ensemble. “I made my own style.” This also worked because Marina was show-stoppingly gorgeous even though she was the last to realize it. “I was not aware what my influence was,” she sighed. “Walter always told me, ‘Oh, you’re amazing’ because I did things an hour before I went out.”

Whenever Marina went to the club, her last-minute, freeform outfits would always get compliments, and she would always offer to show how she made it. “It’s very easy. Just give me a beer and a pen.” She’d grab a napkin and draw out a pattern: stitch there, stitch there, make a tunnel, feed in the elastic. The next time she came back to the club, someone would be wearing a version of her clothes. She loved it. She was living in the world that punk had created. It was style anarchy. “Everyone could feel the spirit of the moment,” Marina said. “Strong individuals with outspoken personalities came to the forefront. We too could feel that. We broke out of the school; we broke away from the laws of the Academy.” Quite literally, Marina almost got kicked out of the Academy because she would disappear for months on end. Marina couldn’t help but feel like she was “wasting time” in this protective academic bubble, keeping up with strict assignments. Especially when she knew she could already create beautiful clothes in her own way.

The legend goes that this group of friends: Marina, Dries, Ann, Dirk, Dirk, and Walter, would go on to become “The Antwerp Six” when they would travel to London together in 1986. When they were placed inconveniently on an upper floor, it was Marina Yee’s idea to create a poster: She saw the convention center had a copy machine, she grabbed some scotch tape, she grabbed the others (shouting, “We’re all going to be famous!”) and they started making flyers that read COME SEE THE SIX BELGIAN DESIGNERS. They were stronger together when they marketed as a group.

Until Martin Margiela’s premiere show. Although they had dated on and off in the past, it wasn’t until after Martin’s stunning debut that Marina and Martin became a couple. This puzzled everyone I talked to, including Marina herself. But Marina followed Martin to Paris, where they lived together for two years.

Although Marina tried to work for a Spanish clothing brand, it proved unsatisfying, and the collection ultimately ended. It was becoming clear that Marina and Martin were living in opposite worlds. “I regularly had bouts of jealousy,” Marina told De Standaard. “I was sometimes furious about what I saw. Things that I had done, or could have done but never did.” Marina was getting weak and losing weight. “What I went through then I wouldn’t wish on anyone,” Marina said. “I was actually at the end of my career, while things were just starting to go so well for him. We were two incredibly kindred spirits, but at the same time there was also competition between us. I sometimes wished I had become a sculptor or a photographer, or at least something else, so that I could have cheered wholeheartedly for Martin’s success.”

Marina left Paris and opened a successful cafe in Brussels. And then she had a career restoring furniture. For a while she taught classes, she designed maternity clothes, stage costumes, and lines for other designers, including Dirk Bikkembergs’ womenswear line.

When I went to Marina’s small apartment in Antwerp, Marina had finally come back to her calling: to impeccable reconstructions of second hand clothing, ever so subtly rumpled in exquisite ways. Her apartment was full of garments she rescued from the street and thrift bins. She would lovingly breathe new life into these garments with elegant little stitches, the way a sculptor chips at marble. She would sew phrases and poetry inside her jackets and give them names. Her collections of found objects were organized in little bins—one for belts, one for buttons. She rolled me cigarette after cigarette and her cat dodged between our legs.

I continued to walk by Marina’s apartment most nights. Not in a creepy way, it just so happened to be on my way to everywhere else in Antwerp. This secret titan of Belgian design was hiding in plain sight. And always, even coming home from a late night drink, I couldn’t help but notice that Marina’s living room light was on. An eternal flame, curtained by houseplants. I imagined Marina up there in her late night laboratory, hauling out boxes of buttons and sifting through piles of thrifted skirts. Taking this refuse, this junk, and ripping it apart. Breaking it down further into the end of its life. Hastening its decay until it is fully reincarnated.

Lead image courtesy of MARINA YEE