Mark Leckey’s story originally appeared in i-D’s The Get Up Stand Up Issue, no. 358, Winter 2019. Order your copy here.

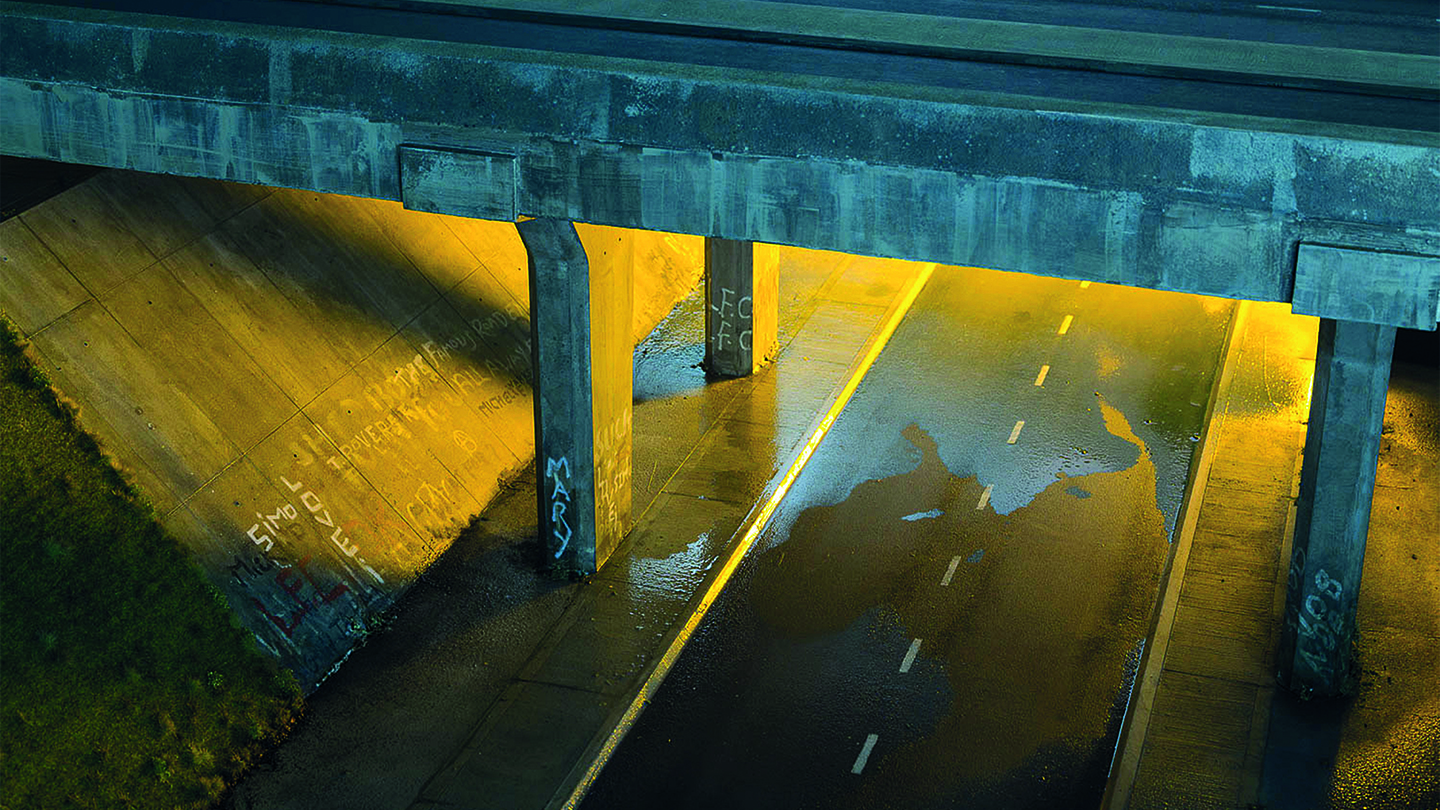

It’s been 20 years since Mark Leckey first released his seminal film, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore. Made in response to the music video format and exploring the organic evolution of musical subcultures, it’s a film that not only asserted the legitimacy of working-class vernacular culture, but also the art world’s historic resistance to it; standing out at a time when the industry was dominated by the capitalist tendencies of Eton-educated Jay Jopling and White Cube, and a whole roster of YBAs willing to get rich quick through the investment of dubiously-acquired wealth. Fiorucci set in motion a career that has always attracted praise from the more discerning corners of the critical press, and Leckey was awarded the Turner Prize in 2008 for his exhibition, Industrial Light and Magic. But bigger, tectonic movements in culture have now also brought Leckey squarely under the mainstream spotlight. Following his show, O’ Magic Power Of Bleakness, at Tate Britain earlier this year, Leckey’s audience has never been so diverse and far-reaching. Drawn by his portrayal of life at the fringes — a world that exists at the end of an A Road under streetlight — he is fast becoming the artist for those whose experiences, despite constituting the majority, have been steadily erased by the forces of neoliberalism from the wider culture. We caught up with Mark to find out how he’s taking it all…

How have you felt as a working class man making work about that working class experience? I know a lot of the YBAs came from working class backgrounds, but so much of their work was essentially ahistorical. You always stood out for that reason.

I mean, things have definitely changed in the last couple of years. I’ve never been adverse to class but now it feels like it demands it in some way. When I came out of art school I couldn’t make anything, I didn’t know what to do, and then 10 years later I ended up making Fiorucci, which was

definitely a sort of response to something. Fiorucci was made out of resentment. I wouldn’t say I was angry, but I felt like the culture I’d grown up with, the music and the clothes — what was called street culture I guess — that there was an intelligence to it, there was a mind, and entering into the art world that kind of culture was too easily or readily dismissed.

There was this continuing idea that art was somehow an avant garde practice, that it was pushing things forward and everything else was just reactionary or conservative. Fiorucci came out of that. It came out of feeling like I couldn’t understand what I was being taught at art school, and that was a class thing. I felt like I wasn’t equipped. I didn’t have the intellectual background to seize those concepts or understand that dense language. So I basically came out of art school feeling stupid and that turned out into slight simmering resentment in some ways.

And then I just thought, well I want to celebrate the culture that I came from. I thought it was equally intelligent and just as, if not more, forward thinking than a lot of what we were being taught in school. I grew up learning to understand semiotics and signs and how to read things and use them and play with them in a very sophisticated way and so, yeah, that was kind of how I started making work.

Were you surprised by the reception to Fiorucci?

Yeah, it was very surprising. When I first made it 20 years ago, I remember thinking it was just a steaming pile of shite. I thought it was maudlin and creepy. I thought people were gonna hate it. And then it got a good reception, although back then the reception wasn’t as immediate as it is now. There wasn’t all these channels of communication to say, well I give this six flaming stars and a thumbs up. It percolated. But the night it showed at the ICA everyone told me it was good and they really liked it, so I assumed that was the way you made art. Then, with the next thing I made, I discovered it doesn’t always happen that way. Even with the Tate show, there’s a new piece that I didn’t get to watch it until the last minute and I just thought “Oh jesus this is so bad”. I had the same anxiety attack that I did 20 years ago just thinking “I don’t want this to go public! This is just horrible.” I read something recently that said we should stop using the term ‘imposter syndrome’ because it’s basically brought on by class…

That was by me!

Oh was that you! Brilliant! It’s good you said that, because every time I read about ‘imposter syndrome’ I’d just be like c’mon. It’s about class, it’s about gender, it’s obviously about power.

Yeah, absolutely. I’ve also been thinking about cultural production and the role that these big galleries play and all of that, and what struck me about your show at the Tate, is that it required participation. It wasn’t a passive experience, it was immersive, you moved around, things happened at different times. Are you interested in the work of groups such as the Situationists, and people who sought to return culture to something outside of the passive, consumer space where it is always intended to bring a return to capital?

Well, I wrote my dissertation on the Situationists. When I was making this show I basically didn’t want to think about it as art. That’s something I normally do, because if you start thinking about things in terms of art then you start leaning toward ideas that are not your own. That’s where cleverness can be an obstacle and it’s that kind of cleverness that I’m always trying to step over. Halfway through making this piece I was thinking: it’s not an expanded structure, it’s not an immersive environment, it’s an attraction. In the same way that Blackpool Lights are an attraction and I like the idea that art can be an attraction, that you can go there and have fun! Or be creeped out. It’s like a haunted house.

Did you go to many haunted houses as research?

No, but I did look at lots of those cursed images online. Pictures of failed attractions. I guess they’ve got that uncanny quality that essentially we haven’t got over in the art world.

In the last couple of years we’ve seen a massive surge of interest in the writings of Mark Fisher – are you into him?

I met him once, he interviewed me. After that I kind of caught up with his writing and I’m a fan.

He argues that the working class and the left need to find a constructive way of expressing themselves and a constructive identity, of getting beyond the hauntological. That’s what your show felt like to me, that we were finally moving into something a bit more tangible.

That’s kind of along the lines of the conversation I had with Mark. I remember reading back over our interview after he died and thinking ‘Oh shit he was asking me some really big, profound questions and I’m just replying quite glibly to them.’ But that’s what he was saying all the time you know, how do you produce this culture that isn’t just nostalgic or based on some idea that the working class still somehow just refers to white working class men. Part of the problem I had at art school is that a lot of it is sort of diagnostic, and I’m not interested in that. I am interested in understanding the pathology of culture and I’m also trying to produce this effect. That’s why I keep talking about… power is the wrong word, charisma is the wrong word. Those words are too masculine, they’re too tainted with that Damien Hirst kind of thing. There is this effect that I’ve seen, particularly through music, that’s forward thinking, often to the point where it’s alien at first. It changes language. It creates its own language. That’s what I meant before about it being avant garde. I guess that’s what I’m still looking for. I still have faith in that idea. But I guess the difference in me is that I locate it within class more rather than something academic. I’m not interested in being academic. The class war is more present now. And there are more channels for people to be heard who have never been heard before.

You have an interesting relationship to digital culture. You seem less nostalgic for a pre-digital era than many artists. How do you think the internet affected you, and what are your earliest memories of it?

You know I’m 55, I grew up in a wholly analogue age. But then I got involved in the internet very early. I did web design back in 94, and I learnt HTML in America, I went to live in America, in San Francisco for a bit too. I had quite early involvement in it. I remember over here there were some organisations starting up and the first flourish of excitement around quite a utopian idea of what the internet was gonna bring back in the early 90s. I think that’s part of where I’ve come from. I feel slightly cybernetic in that sense. There’s a slightly arthritic old analogue part of me that I’ve had to upgrade… no that’s a really terrible metaphor. But I’ve had to adapt. No not had to adapt. I was eased into it. I had an easy time, I fell into it. I’m waffling now.

No, no! I think that’s very interesting.

I did this talk a long time ago called The Long Tail. Do you know about this theory? It’s sort of dismissed now, everyone thinks it’s ridiculous. But it was this theory by Chris Anderson who wrote for Wired, and the theory was that analogue production was all condensed into this head and what you would see through the internet is this kind of long tail of distribution. So rather than something like Top of the Pops you get this infinite distribution of different niches. That’s been realised in music more than anything else. But then, you know, now you’ve got Amazon, Facebook, these big giants, all the rest of it. You’ve got these monopolies again so everyone thinks this Long Tail

idea is ridiculous. But I still see it at work. I think it was at work with Trump, I think that was how he consolidated his fanbase. But also you see it generally, on social media, how these different interests can come together and consolidate momentarily by using their collective power. I find that really exciting and interesting. I still think the internet has positive potential. And when people talk about Twitter spats I’m like yeah but look what it’s doing, it’s fucking amazing. I mean the people I follow on Twitter, it’s incredible. I basically get educated through Twitter now. I go on there and listen to people whose opinions I might have a kneejerk reaction to but then I start to follow them and listen to what they’re saying and they persuade me, you know what I mean?

Yeah I’m the same. It’s basically my homepage.

Yeah, exactly. I still find that quite exciting. I don’t hark back to some great analogue rave era. It was a thing and it was beautiful but it’s gone. I was there and at the time there was all this nostalgia for the 60s. It was just this idea of looking for something authentic through something that’s already a fiction, something that’s already been mediated, it’s impossible.

Do you teach at all?

Not so much anymore, I used to. Art school’s a funny thing at the moment because there are fewer people from my kind of background there at the moment, but there are still interesting people there and it’s much more cosmopolitan than when I went. I find parts of it very frustrating, but then that’s part of teaching, being frustrated. That’s part of the job. I’m looking to teach at a younger level, like sixth form age. I tried it recently and it’s much harder but I’m going to persevere. I’m just trying to find some way, some access, for people who might not otherwise get into it.