By the time Destiny’s Child released their sophomore album The Writing’s on the Wall in July 1999, lead single “Bills Bills Bills” had already spent six weeks on the Billboard Hot 100, with one sitting right at the top (they knocked Jennifer Lopez’s debut, “If You Had My Love” from the spot earlier that month). In spite of the accompanying hype, when he was commissioned to shoot the group for Vibe magazine later that year, Markus Klinko was ignorant of their success. “They were just these young girls who came to my studio with the mom, Tina,” he recalls.

“But as soon as I started shooting I noticed this incredible charisma. I remember specifically pointing to Beyoncé and looking at her mom, who was styling. I said, ‘this one in the middle, she’s gonna be huge’. Her mom just said, ‘oh yeah, we know’.”

Speaking over Zoom from Los Angeles, a city notorious for its proximity to stardom, the Swiss-born photographer initially found little interest in working with celebrities, preferring to focus solely on models. “But my style appealed mostly to record labels, advertising agencies and celebrity publicists, so I needed a lot of convincing from my agents,” he says. Despite these early protests, he has since manufactured a multi-decade career informed by the trust and intimacy established with his famous subjects. Working closely with some of the music industry’s most celebrated performers, his name has become synonymous with the 2000s and an aesthetic beholden to Photoshop in particular. Moreover, for a significant number of millennials, his photographs were fundamental in shaping their visual language.

“People say to me all the time, ‘oh, I was 14 when this came out and I had the poster in my bedroom’,” he continues, alluding to the weight of his earlier assignments. In 2003, for example, he collaborated with Beyoncé again, this time on the imagery for her debut solo record, Dangerously in Love; while in the same year he worked with Kelis on Tasty, widely regarded as her commercial breakout. A campaign with Britney Spears followed, and two years later Mariah Carey tapped him to shoot her for the release of The Emancipation of Mimi. More recently Markus has shot Billie Eilish for Vogue and Ice Spice for Paper, while his 2002 cover art for David Bowie’s Heathen is a favourite amongst galleries and will make a cameo in upcoming A24 series, The Idol (courtesy of The Weeknd’s personal collection).

A former harpist, photography wasn’t a big part of Markus’s initial career trajectory: in the early 90s he was a touring musician. “My father was a symphony orchestra musician, and early on I was forced to play piano,” he says. “Around age seven I discovered Elvis and was allowed to play the classical guitar, which I loved. Then I became a classical concert harpist, signed with EMI Classics and recorded several albums.”

A relative anomaly — a young guy playing the harp — Markus appeared in several fashion magazines and grew privy to the framework of the industry. When in 1994 a mysterious hand injury left him unable to play, he decided to switch it up and teach himself to use a camera. “I had zero experience but a lot of self-confidence,” he acknowledges. “I bought a book by Ansel Adams and a lot of expensive equipment.”

Living in Paris, he secured an agent and was commissioned for campaigns and fashion editorials, quickly immersing himself in digital post-production, then in its infancy. His glossy, overly-airbrushed aesthetic was built around this new technology, while his music career was similarly influential he says. “The type of music I played was very colourful — most of the harp repertoire is Debussy and Ravel, French impressionists — so I developed an inherent taste for colour,” he says, noting how he translated that sense of drama to his image-making. At the time this style was considered wholly commercial, and too much by some, especially in comparison to the raw sensibility employed his contemporaries working for youth culture titles, but things have changed he observes. “My work for Beyoncé is very colourful and bright, so when that came out someone would’ve looked at it and said, ‘Oh, that’s not cool enough for us, that’s not street or lo-fi enough’. Now it’s a signature aesthetic of the 2000s — it’s no longer really commercial but just a moment in time.”

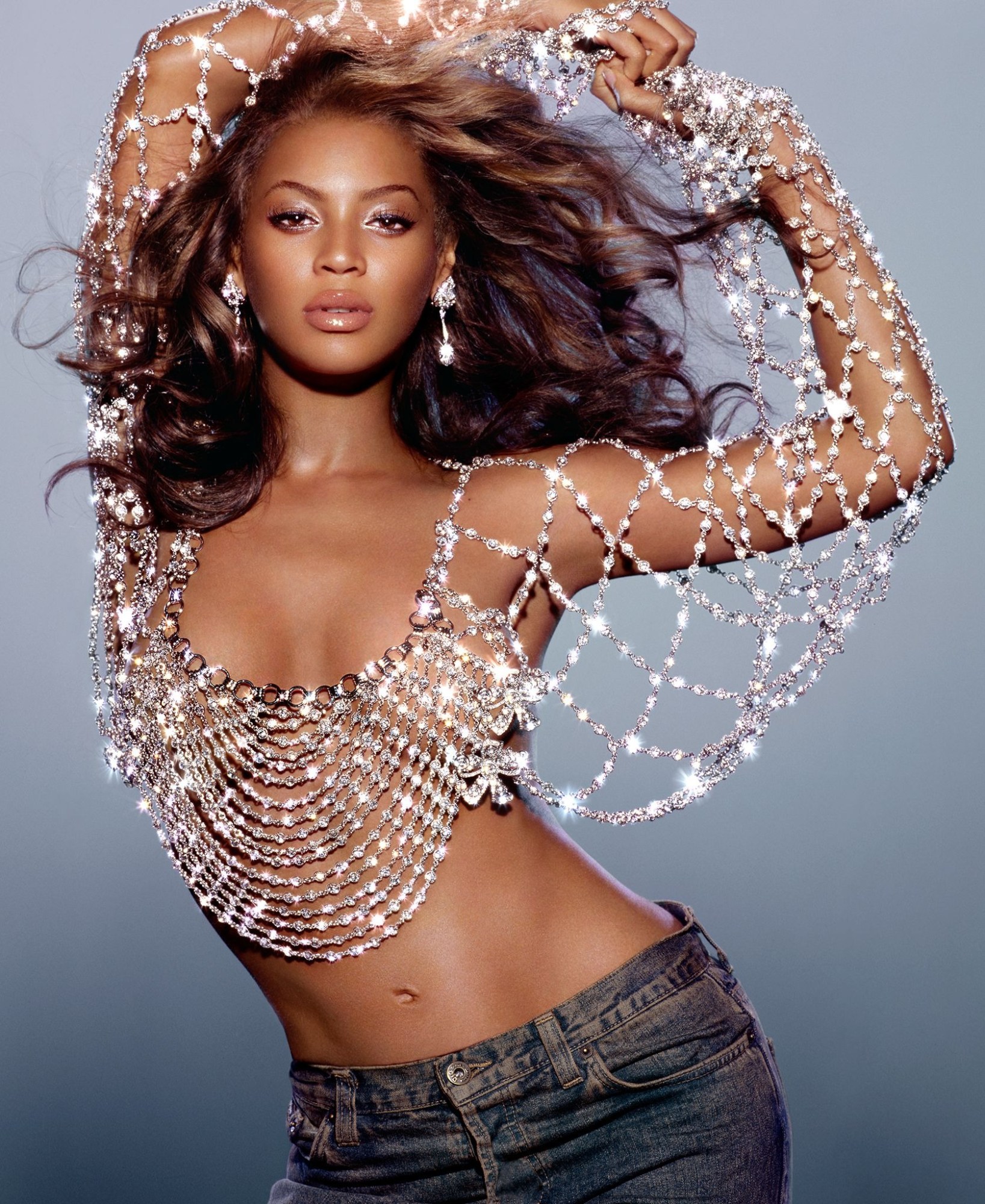

With Dangerously in Love and Tasty both turning 20 this year, a wider, revised assessment of his contribution to contemporary pop culture is no doubt set to follow, not least in the case of the jeans-and-a-nice-top aesthetic, for which the Beyoncé album cover was pivotal. Inspired by an earlier shoot Markus had done with Laetitia Casta, in which the French model is tangled in a shimmering spider web, the now-iconic look was something of a happy accident, with the diamond top initially dismissed. “Tina had brought all these long skirts and Beyoncé thought it would look too red carpet,” remembers the photographer. “I suggested she should wear it with denim, that it would be this cool juxtaposition. They didn’t bring any denim, so I just said ‘maybe you could wear mine.’ I didn’t really think about it that much.”

Tasty, a more playful affair visually, was also the product of an editorial meet cute, following a shoot for Interview magazine. “Kelis had all these ideas [for the album cover], and told me the story that she used to be a waitress at a diner, and how the milkshake she used to serve inspired her song [“Milkshake”],” says Markus. “She went back to the diner and put it all together, they brought it over in an icebox and I shot the milkshake that she art directed. She became one of my favourite collaborators.” Reflecting on his practice and these relationships, Markus attributes the sense of trust to his stint signed with EMI. “It’s helped me make people feel at ease; to connect on a deeper level without having to speak much. I understand, in a certain way, where they’re coming from.”

While the common thread in his work is an element of fabrication, Markus is untethered from any one reference pool, instead drawing from what he sees and hears around him. Pressed on a specific influence however, he cites Andy Warhol. “Obviously I’m not a painter, and I wouldn’t directly compare myself to him, but the business model and how Warhol so successfully documented pop culture [inspires me]. How he worked with celebrities, took that culture and really created art out of that; not seeing difference between what’s commercial and what’s art,” he shares. It’s not hard to read his own catalogue as a kind of modern day example of the late artist’s ideas about fame.

“It’s interesting; celebrities would go to The Factory, get photographed, and then Warhol would put them in his shows — that pop culture moment was very much existing around the artist. And I feel that’s kind of what’s happening now, and what makes me excited.”

Credits

Images courtesy of Markus Klinko