Last month saw the release of Listen to Me Marlon and Amy, two prismatic but different documentaries that arrive at a similar conclusion: that the blood of their eponymous stars, Amy Winehouse and Marlon Brando, is on our hands. More importantly, the bloodshed won’t cease until we examine and correct our carnivorous treatment of celebrities.

From The National Inquirer to TMZ, there’s a world of “journalism” predicated on exploiting the misfortunes of the famous, all in the name of transparency. As Nick Denton, the founder of Gawker, whose company appears to be unravelling right before our eyes after outing a CondéNast employee, famously said in a memo to staffers, “We believe that the best web content optimization strategy is something as old as journalism itself: the shocking truth and the authentic opinion”.

It’s true that journalism has a long history with what Denton calls “the shocking truth,” and we’ve always been enraptured by the personal lives of stars.

But Gawker’s raison d’etre has little to do with transparency. Denton’s approach to reporting, which was ushered into the 21st century by the Perez Hiltons of the world, is about destruction. A cursory scroll down the Gawker frontpage will reveal headlines like, “Meek Mills: No, Really, Someone Peed on Drake in a Movie Theater” (kind of funny) and “Billionaire Republican Who Mocked Hillary Clinton’s Marriage Had an Ashley Madison Account”.

Our desire to read this lewd material has grown and been exacerbated by the internet. We’re in a golden age of sado-journalism where the aim is to obliterate those in the spotlight by unveiling and critiquing their foibles. We gleefully profit from others’ pain.

But this profiteering on the shortcomings of the famous is not profound art. A hundred years from now, no one will be awe-struck reading The National Inquirer’s “exhaustive” investigation into the death of Robin Williams (an article that posits Williams did not commit suicide but was, in fact, murdered). What we’re churning out on a daily basis at breakneck speeds is mindless ephemera that evaporates into thin air just soon as it takes orbit. The life cycle of these pieces range anywhere from 20 to 30 seconds. And to the standard consumer, these vicious attacks go in one ear and out the other. But what about the subjects of these affronts?

It’s clear Brando and Winehouse had the talent necessary to garner attention, but if Amy and Listen to Me Marlon are to be believed, neither had the capacity to withstand the gaze of public eye. Whether it was the disintegration of Brando’s family or Winehouse’s romantic life, each artist was forced to endure an opportunistic media, desperate to please their insatiable readers.

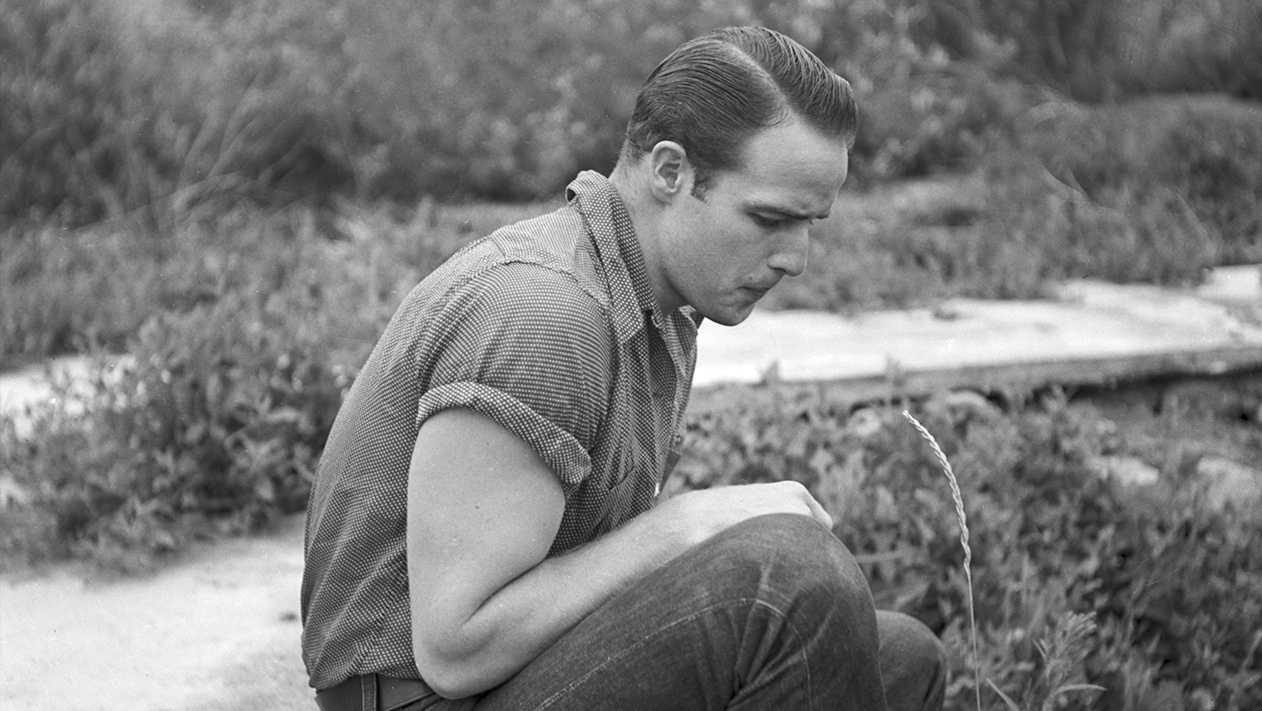

Amy and Marlon are vulnerable because their personalities are built on their genuineness; their art sits atop their unabashed honesty and openness. In Amy, documentarian Asif Kapadia utilises home-video footage to paint a vulnerable portrait of an artist, youthful and zit-faced, excited to simply make music. Similarly, Listen to Me Marlon director Stevan Riley cobbles together hours of Brando’s audio recordings to exhibit the method actor in all his complexities. Brando and Winehouse, in their own unique ways, were mentally troubled, wholly sincere individuals. Tender and thoughtful, they spoke from the heart — a quality evident in their creative output.

Unfortunately, sincerity is often anathema to stardom, or at least the one-dimensional “stardom” of Hollywood. Marlon once claimed the only reason he was still acting was that he “didn’t have the moral courage to refuse the money.” Instead of allowing figures like Brando and Winehouse to be themselves, their lives get reshaped and refigured into inanimate public spectacles for the press to feed off. Soon these fictitious public personas begin to take over and the individual inside the silver screen or in front of the album cover fails to keep up. After all, who the hell could?

Toward the beginning of Amy, the titular artist struts into a meeting with various music producers. They kindly ask her if she could offer a little taste of what Frank — her debut album — will sound like. With an endearing mélange of confidence and nervousness, a young Winehouse picks up her acoustic guitar and begins to sing. The room is transfixed. As soon as she utters those first words (“I couldn’t resist him…”), everyone watching understands they’re in the presence of greatness — a talent that comes around about once in a generation.

The scene goes on and she continues to pour out her soul. “What do you expect?” she frustratingly inquires, “You left me here alone; I drank so much and needed to touch.” Later titled I Hear Love Is Blind,the song revolves around a woman describing, to her boyfriend, a sexual encounter she had with another man. The character justifies this act by claiming, “it’s not cheating” because “love is blind.”

It’s a pivotal moment in Winehouse’s career, and even more so for the audience. Perhaps that same love, that admiration we have for celebrities, blinds us, too. Swept up in our all-consuming veneration for Brando and Winehouse, we become lost in them. We lavish them with superlatives when they’re up and kick them to the curb when they’re down.

Marlon once said to Truman Capote in a profile for the New Yorker, “The more sensitive you are, the more certain you are to be brutalised, develop scabs, never evolve. Never allow yourself to feel anything, because you always feel too much.”

It could work as a mantra for both the audience and actor; throughout it all, we avoid humanisation, so horribly afraid that when the cameras stop rolling and the lights come up, these icons will appear just as idiosyncratic and flawed as the rest of us.