Few people have played such a major role in avant-garde fashion over the last 30 years as Martin Margiela. His work has inspired countless designers. Raf Simons, who saw Margiela’s iconic White show in 1989, has confessed that it inspired him to shift directions from interiors to fashion. As Marc Jacobs said in 2008: “Anybody who’s aware of what life is in a contemporary world, is influenced by Margiela.”

In 2019, however, 31 years after Martin launched his label, the Maison and its founder are experiencing something of a victory lap. The usually hermetic designer is stepping out to soak up (some) of his glory. First off there’s the long-awaited documentary, Margiela in His Own Words. The film, directed by Reiner Holzemer, will offer unprecedented access to a man who has meticulously avoided the glare of the spotlight.

Secondly, this year, a decade after after he sold Maison Margiela to Renzo Rosso and resigned as creative designer, and 30 since he became the first recipient of the ANDAM Fashion Award, he’s returning to judge the prize that helped make his name. In a rare statement, Martin spoke about leaving the industry and the state of fashion today.

“Many say that fashion has a short memory as it is obsessed by actuality and novelty. But some recent exhibitions about my work exemplified the opposite,” he said. “Again, my homeland Belgium was the first to honour my work at the MOMU Antwerp, and then my adoptive city Paris followed with two more, at Palais Galliera and Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

“A beautiful tribute to a period of hard work and dedication starting at early age and lasting for more than 30 years, until 2008 — the very year I felt that I could not cope any more with the worldwide increasing pressure and the overgrowing demands of trade. I also regretted the overdose of information carried by social media, destroying the ‘thrill of wait’ and cancelling every effect of surprise, so fundamental for me. But today, I am happy to notice again a growing interest for creativity in fashion, by some upcoming designers.”

Given how far reaching and pervasive his touch on the world of fashion has been, and to mark this special year in his history, we asked four people who knew and worked with Martin Margiela about his influence on them and his enduring legacy.

Kristina De Coninck: “My First, My Last, My Everything”

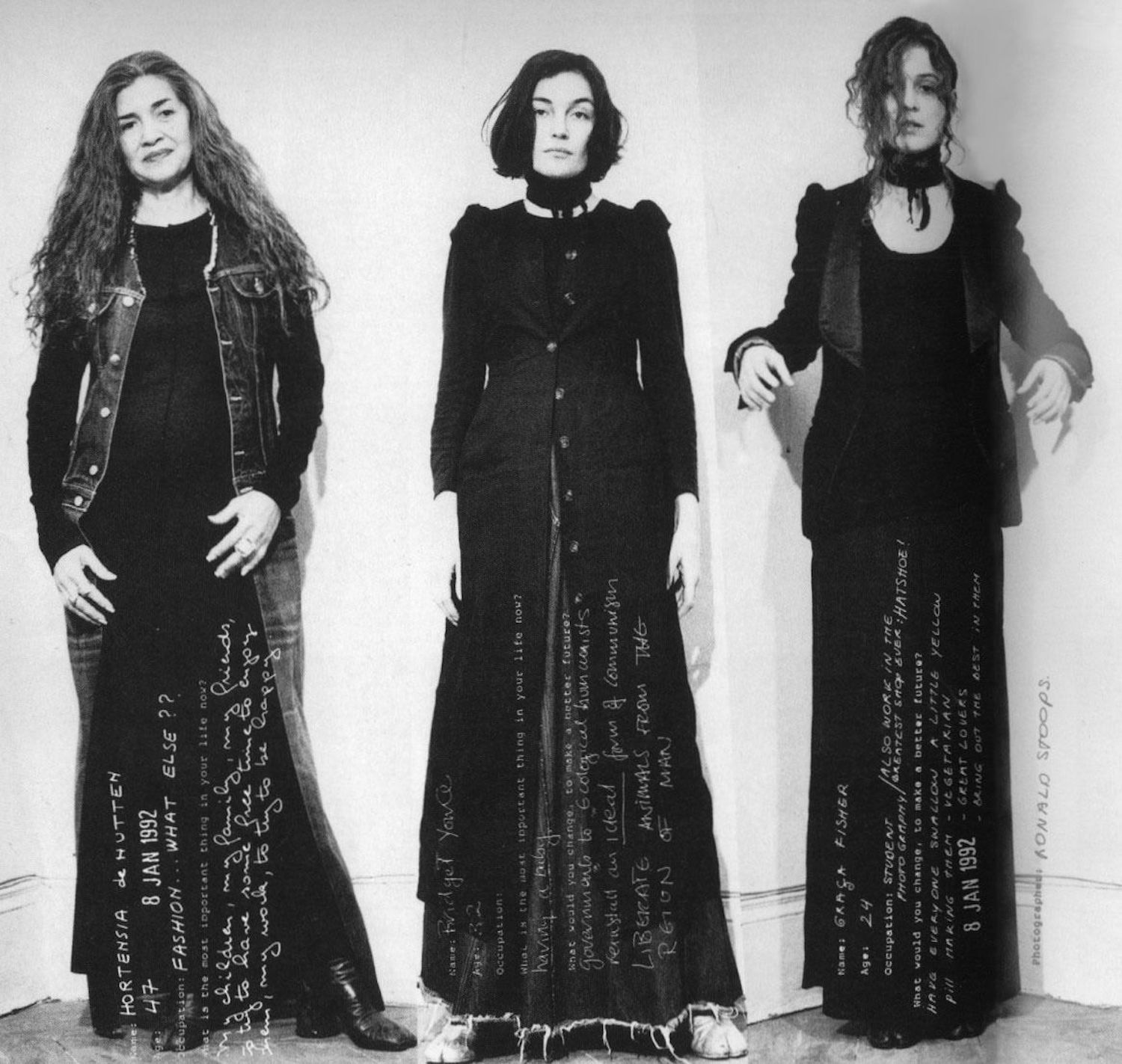

Fellow Belgian Kristina De Coninck, was an artist who became Margiela’s favourite model and muse, and they’ve remained good friends until this day. Kristina became a model almost by accident, when at 26 she was scouted in an Antwerp café, where photographer Ronald Stoops (husband of Margiela’s favourite make-up artist Inge Grognard — Antwerp really is a small town) earned some extra money as pulling pints.

He convinced her to go to a casting call for designer Dirk Van Saene, one of the Antwerp Six. Martin Margiela saw the resulting shoot and the rest is history: Kristina moved to Paris, rented a tiny apartment and started to work with Martin.

“Martin showed so much respect to all of us, in the way he was talking about the models. Many of my happiest memories with Martin are related to the music we listened to, we had so much fun together! In one of his shows — at The Conciergerie in Paris — and also during his exhibition in the Musée Gallièra last year, he included my favourite song: Loving You by Minnie Ripperton. Can you imagine how that made me feel? So much joy!

“Then I think about the moments where we had some crazy laughs, moments that I felt so understood by him. The moments when I saw him working, he was so focused, often I would just melt watching him! Often Martin showed me what he had made, it was not fashion, it was totally different, it was original and I still know what it looked like. I was touched that he shared these moments with me. Thanks to him I learned that in life you need guts, courage, determination… but all these strong words only make sense when there’s also a place for sensitivity, tenderness, attention, devotion, taking care and believing in yourself.

“To abstract an entire life in one sentence is not that easy, but I am thinking about a love song, Barry White’s My First, My Last, My Everything and dancing together with him — heaven!”

Jean Paul Gaultier: “I admire him for his uncompromising stance on creation”

Famously Martin Margiela’s first job in Paris was working for Jean Paul Gaultier, who has called him the best assistant he ever had.

“I was on the jury at the Antwerp Academy for the graduate show of the class which is now known as the Antwerp Six. Martin was a year older and I had heard about his work but had not seen him. A friend of mine who worked at the Libération newspaper asked me to see him. When I met him and I saw his work I told him immediately that he was ready for his own line and that he didn’t need an apprenticeship. But he insisted that he would like to work with me. He stayed with me for three years, he was my best assistant, he became my friend, and when he told me that he wanted to leave and start his own line I could only wish him good luck.

“I think that some of the things that he decided to do were in reaction to what he saw while working for me. I was part of the first generation of designers who were starting to get mediatised and he chose total anonymity, to never be photographed or interviewed. I think also that we share the love for le trompe à l’oeil and reinterpretations of the classics. I have always admired him for his uncompromising stance on creation and for his strength to stay away from fashion once he had decided to stop.”

Sonja Noël: “I didn’t know what to think of his first collection: was it beautiful or ugly?”

Brussels shop owner Sonja Noël is as passionate about fashion today as when she opened her first store Stijl, on rue Dansaert in Brussels, where she sells brands such as Ann Demeulemeester, Rick Owens, Haider Ackermann, Dries Van Noten, Y/Project, Raf Simons and Martin Margiela. She opened the first Martin Margiela shop in Europe in 2001, in a 18th century house in Brussels.

“I remember his first show very well — mostly because I couldn’t attend it, as I was having my first baby on that day! I watched a video of the show afterwards, saw the clothes in his showroom and didn’t know what to think of the collection: was it beautiful or ugly? Margiela cut jackets with very narrow shoulders and sleeves, at a time where everybody else showed jackets with wide power shoulders. His wide trousers had pre-made knee shapes in them and the seams were raw and unfinished. In a way I loved it, so I ordered the entire collection — and got the showpieces, since Martin’s first collection didn’t even go into production. I still have some of those pieces and plan to donate them to a fashion museum in Brussels.

“Then when I opened the Margiela shop, he came over from Paris to tell me how the shop should look — he took photos of everything and drew on them with a white marker. We put in old wooden doors, heavy glass windows, white marble floors, crystal lamps… everything was recycled and got a lick of white paint, we put white gauze on the lamps and made the shop look intimate. Martin knew exactly what he wanted and I respect that a lot.

“His work was always a revelation, always new and surprising. From the locations of his shows to the invitations he sent out to the media and the buyers, his choice of models… how their hair and make-up was done. Then there were the collections themselves, he didn’t do pre-collections, so, as buyers we never knew what to expect. Martin gave us so many ideas in his 20 years that it will inspire designers for years to come.

“He was an artist. In his refusal to communicate about his designs — his clothes told his story. He influenced the way that I think about fashion enormously.”

Demna Gvasalia “To destroy in order to create”

Demna Gvasalia had his first job after graduating from the Antwerp Royal Academy of Fine Arts at Maison Margiela in Paris. He is now one of the most lauded designers working, the creative director of Balenciaga and at his own label VETEMENTS, where he has constantly paid tribute to the energy and spirit Martin instilled in him.

“I think of my time spent working at Margiela as a sort of masters programme after graduating from Antwerp. Working there I discovered that beauty can be found in everything around us, mundane objects can be turned into creative concepts and become a completely new product.

“I never worked with, or met, Margiela himself, but through the work that I discovered in the archives I educated myself, he sparked my curiosity about clothing. I discovered that creativity can mould something great and completely new from left-overs and next-to-nothing. Margiela made me ‘think clothes’.

“His approach justified for me the idea that creativity needs to be limitless. I learned at Margiela that one can make a garment from an old supermarket bag. I also discovered the immense creativity that comes from having limited resources. In this way it justified my own creative identity.

“At Margiela I learned more about clothes, about falling in love with them, turning them inside out or upside down, all the things that I’ve loved ever since I can remember. At Margiela I learned that you may need to destroy an old garment to create a new one. This may be one of the most important things I learned from the legacy of Margiela: to destroy in order to create.”