This story was originally published by i-D France.

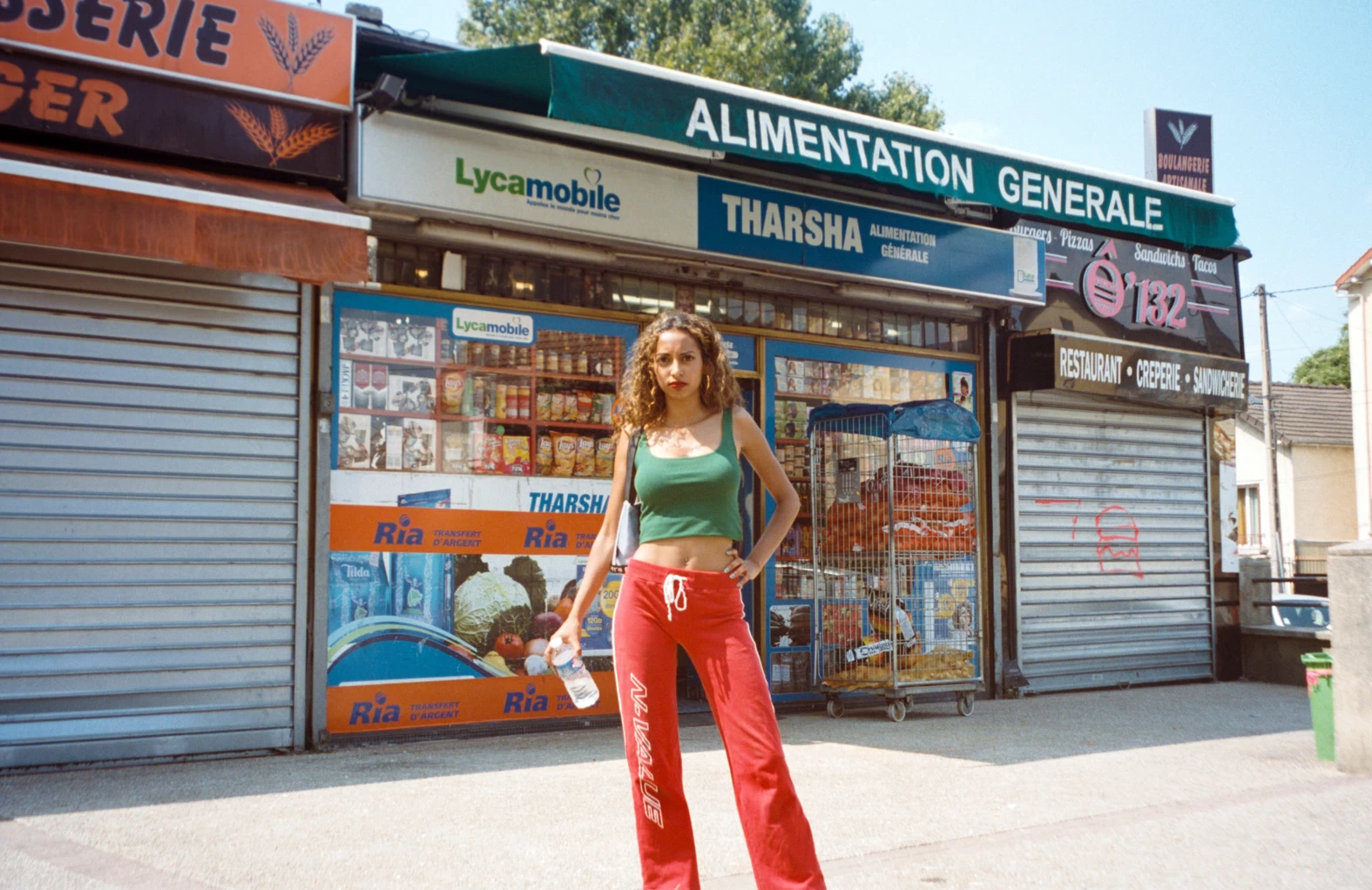

Over the last few years, curious Parisians, for better or for worse, have opened up to suburbia — exploring it to rid themselves of the hasty preconceptions that French society tends to apply to its suburbs. But seldom do we wonder what goes on in the mind of a young person who experiences that same crossing the other way around. That is, the mind of a young person raised in the projects, who has spent their entire childhood fantasizing about Parisian nights, and who suddenly experiences a redefinition of his identity when the inner city finally opens up to them, bringing forth new dialects, new dress codes, and new cultural references. This has been the experience of Marvin Bonheur, a 27-year-old photographer raised in the 93 suburbs and a resident of Paris since 2014. It’s this unsettling arrival to Paris which sparked his first collection of pictures, Alzheimer, combined with the desire to re-engage with his suburban culture, so often negated by Paris and downplayed or dramatized by society at large. We discussed this with him just over a year ago. Marvin had shot the iconic places and architecture of his childhood and teenage years, along with the scenery and lifestyles of these marginalized existences. His follow-up is Thérapie, the second installment in a trilogy in the making, on view at Floréal Belleville until November 7. After having mapped out his suburban spaces, from Aulnay to Bondy and Villepinte, Marvin sets his focus on the people, the faces, the smiles, and the emotions which arise in these areas as his own personal therapy, teaching himself and the world about the richness of this suburban culture. i-D chatted with Marvin about Nike “Requins,” and what comes after Alzheimer and Therapy.

Can you start out by coming back to your Alzheimer collection ?

Alzheimer began in 2014, when I moved into Paris. I experienced a minor cultural shock, due to the gap between Parisian lifestyle and my childhood and education mainly spent in the 93 suburbs. I came to wonder whether I truly had a culture. I had cultural references that my colleagues from Paris or provincial towns did not share, and vice-versa. And since I’d taken up photography a couple of years prior to that, I came up with the idea of shooting a series that would talk about me and my memories. This allowed me to go back to my childhood, to the spaces I grew up in, in order to reconnect with myself. And also to practice photography in a space and an environment that I knew intimately. It wasn’t called Alzheimer to begin with, it was just a series I shot for myself, with snaps of my memories. It went on for almost three years, and over time the project gained in consistency, as new ideas came to me. I found myself anew.

How did the follow-up come to be ?

The follow-up came to be in 2017, upon the release of Alzheimer. I was questioning whether I should stop shooting in the suburbs and focus on what I was doing in Paris or my travels. But a vast number of questions and misunderstandings arose in reaction to Alzheimer and its somewhat exclusive edge. I thought it was crazy that it was seemingly so incredible to display these architectures and scenes of daily life which were all but familiar to me. I told myself that it would be interesting to develop the exploration of this culture, or at least to discuss it more in-depth. To go into a stage of therapy, both for myself and for the people who know nothing about the 93. To “teach” them about this environment, to show them the faces which inhabit it, the emotions encountered there and the daily lives of the projects.

Did you also experience a form of withdrawal?

I’ve been living in Paris for five years, in the 17th district, and when I come home every weekend to visit my mother, my siblings, and my mates, I clearly see that my language also changes. Words that I hadn’t heard in a while come back to me, and a form of communion. It sounds silly but when I have lunch with them, it’s clear that everything is shared without a second’s hesitation, no questions asked. Those are things that I’d somewhat forgotten. It really brought me back to my senses. I’ve found my home again. Like so many youths from the projects, I had spent my childhood wishing that I could leave at any cost, to go to Paris or abroad. And the truth is: it’s bullshit. In fact, I’ve come to realize that there was a super interesting culture and extremely positive side to life in the projects. That’s what I set out to show, without turning a blind eye on certain truths which are not necessarily pleasant to witness, but which do exist.

It’s interesting, there’s not much discussion about this injunction to change when one crosses the “ring road” from the suburbs into Paris. To change one’s language, and sometimes one’s apparel, because of the preconception that there might be rejection. And it’s crazy to be so far, but yet so close.

Exactly — this is why I use the phrase “mini-worlds” so often. I already used it for Alzheimer. It’s a way of renaming the community space. Because whether you’re in Villepinte or in Bondy-Nord, you’re still in small villages, with their own idioms. So even when I shot Bondy, Aubervilliers, and Aulnay, I encountered a ton of similarities, because they’re all suburbs, they’re all set in the 93, but each location comes with its own miniature world. They’re mini-countries. And of course, being isolated comes with its ups and downs.

Coming back to the title, is the “therapy” primarily related to your own experience ?

Definitely. This word is relevant for myself just as much as it’s intended to resonate with the audience that will see my work. My main sources of inspiration are my own wishes and desires. My primary goal is myself. I do this for myself. Then, once a picture is taken I make it into something “commercial,” I want to show it to others, to sell it to others, to share it. But it all starts with me allowing myself to be guided by my emotions and my memories. There are faces that I really wanted to photograph, emotions that I really wanted to capture.

Did the trilogy format come to you from the start ?

No, rather when I started to work on the second part, three or four months after I’d gotten into Thérapie, around the end of the summer of 2017. It was never my intention to lock myself into this but I’m aware that there’s an audience that enjoys my work because it’s rooted in the suburbs. That is very interesting, but I don’t want to get too focused on this and to restrain myself from exploring other topics. I want people to understand that my approach is not targeting one specific point. Even if I stay in one specific space, it has more to do with socially minded photography than with pure “projects art.” I did a series of photos in Martinique, and that’s what I’d like to cover next: the suburbs and the working-class neighborhoods on the islands — remain focused on working-class environments, but on an international level. The idea was to establish an action plan for my work in the suburbs, and a trilogy seemed like the best option I had in the sense that I had a starting point, a centre, and closing series. So a third installment should come out in the coming year.

Over the past few years, we’ve witnessed a resurgence of suburban aesthetics, through cinema, music videos, and fashion. Do you see that as a positive fact or as a form of capitalization which could encourage fetishizing environments that people are unfamiliar with?

I’ve got a mixed opinion on the matter. On one hand, we can display our culture, our values — and show that we’re not “de la racaille,” scum. But at the same time, is that really what the people living in suburbia really want? Take the Nike Requins: when I see Parisians wearing them, I can’t help but smile. I know that their parents were shitting on the lads that wore them five or 10 years ago. Today, their children wear them because they’re hype. Good for them! Those who were stuck in this dress code ideology are now a bit confused. Matthieu from the 16th district, now that he’s wearing Requins, does that make him scum? In the past, that was all it took. But then, that person wearing Requins, has their perception of suburbia changed just because of it? Are they still scared of the youths from the projects? This is why I’m uncertain. When I come into Paris, with my photos, I find myself in exhibition openings and I meet people who dig my work. But if I asked them to join me for a weekend in Aulnay, I’m not convinced they would all show up.

What would you want people to take away from your series ?

I wanted to inform and somehow “educate” people. This Greater Paris thing is cool, but one needs to be careful in the process, to care for the people who live in these areas. These spaces have a culture, a life, a history. You shouldn’t just demolish in order to build something bigger and think, “There we are, this is the Greater Paris.” We’re not like Americans, coming in to displace the indigenous people. This is an excessive image, but there is some of that, on a much smaller scale. People are thriving in the suburbs. Despite all of the issues, they have their culture, their language, their codes and their lifestyles. What I tried to do with Thérapie is to put together a small booklet, to show how things are in our neighborhoods. And if people really are interested in the 93 — and I hope that they are — then they’re welcome here.