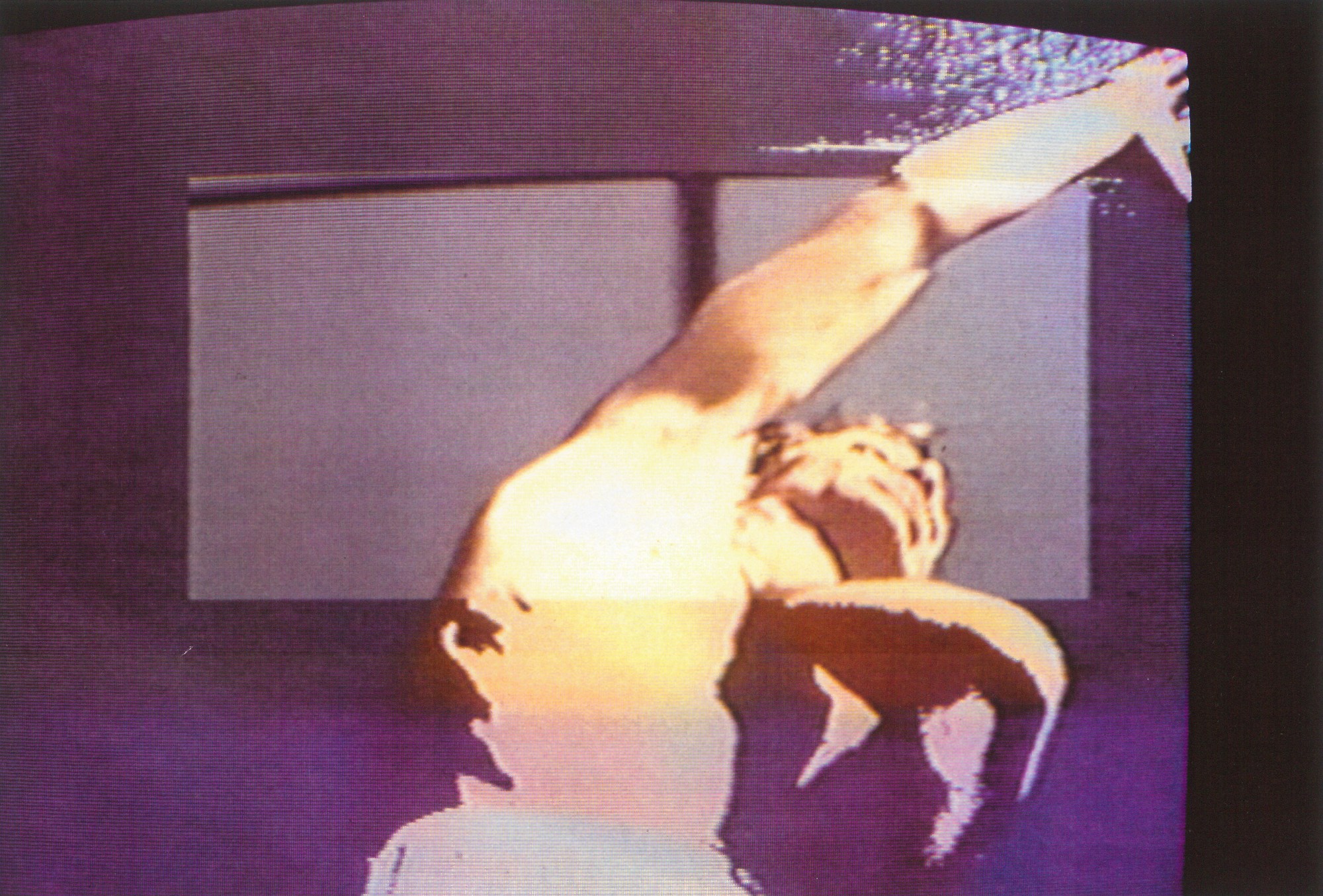

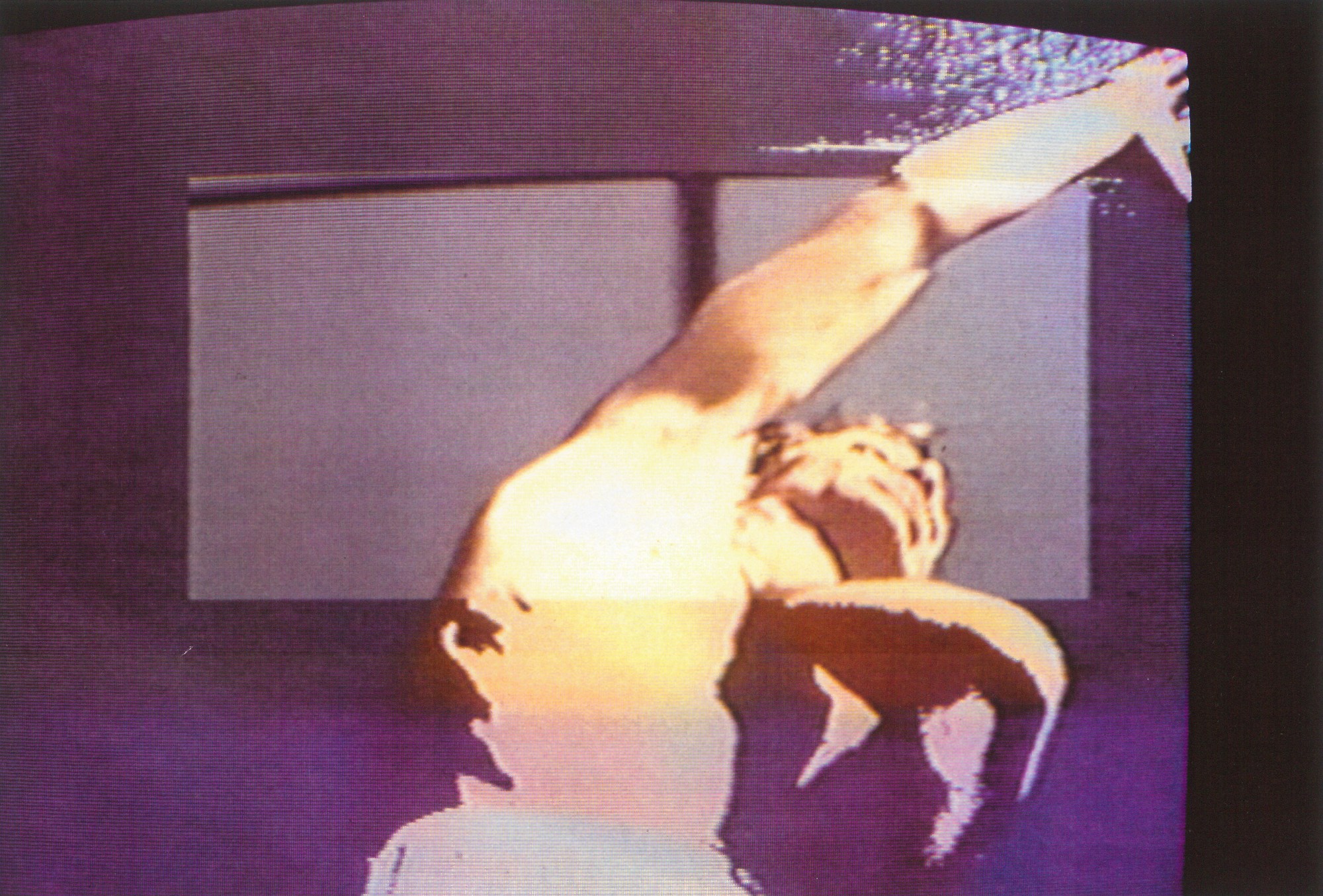

Smoke seeps onto a pristine white runway as two men crawl out from backstage to the drone of an 80s synth. They stand up looking confused, as though they’ve ended up on stage by accident. One pulls on a jumper and the sound of thunder crashes through the auditorium. The men gaze up at the ceiling in anticipation. As if in a panic that the weather is about to turn, they begin to put on layers and layers of clothing. A knitted jumper around the neck, a jacket on top, another coat on top of that. As they pull their hoods over their heads, the spitting sound of rain begins.

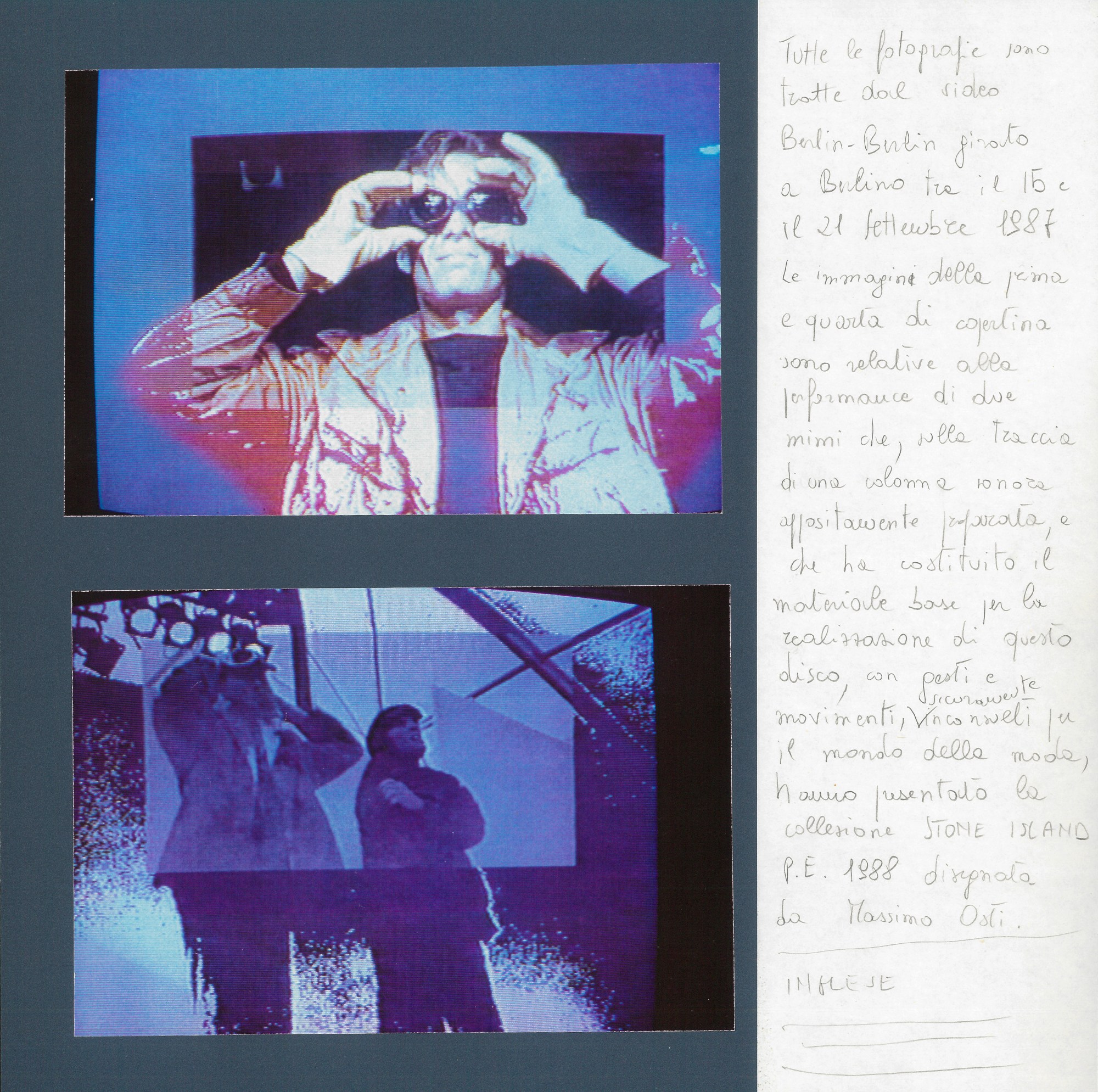

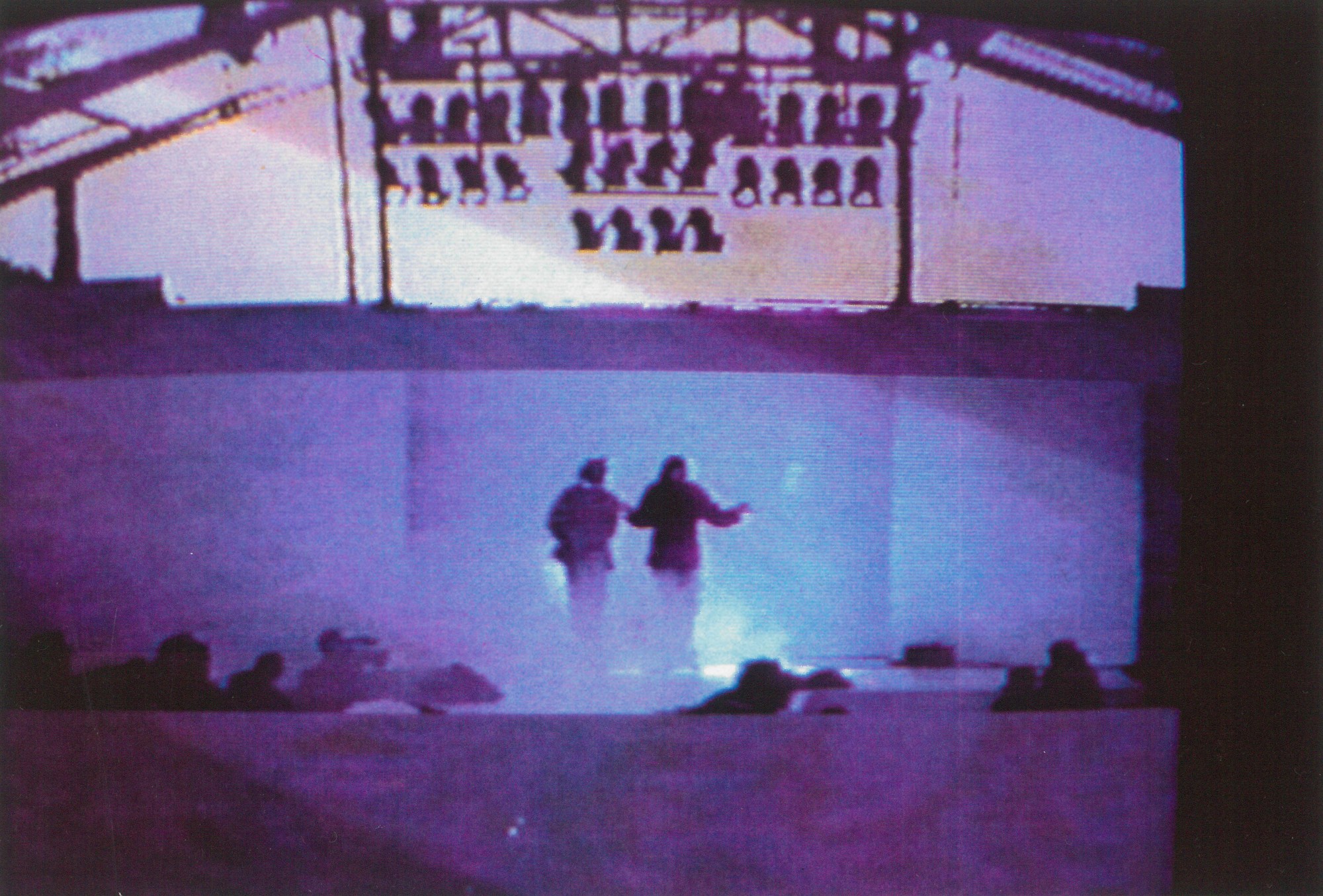

This is the opening sequence of Italian designer Massimo Osti’s first and last ever fashion show. It was 1987, and Osti had been invited to Berlin by the West Berlin Senate. The city had asked him to organise a runway show and an exhibition of his work at the Reichstag, the seat of the West German government, where he debuted his now-famous way of displaying garments squished in between two pieces of glass. The events celebrated fifteen years of Osti’s work as a fashion designer, as well as the 750th anniversary of the formation of Berlin and the 150th anniversary of the mass production of ready-to-wear in Germany.

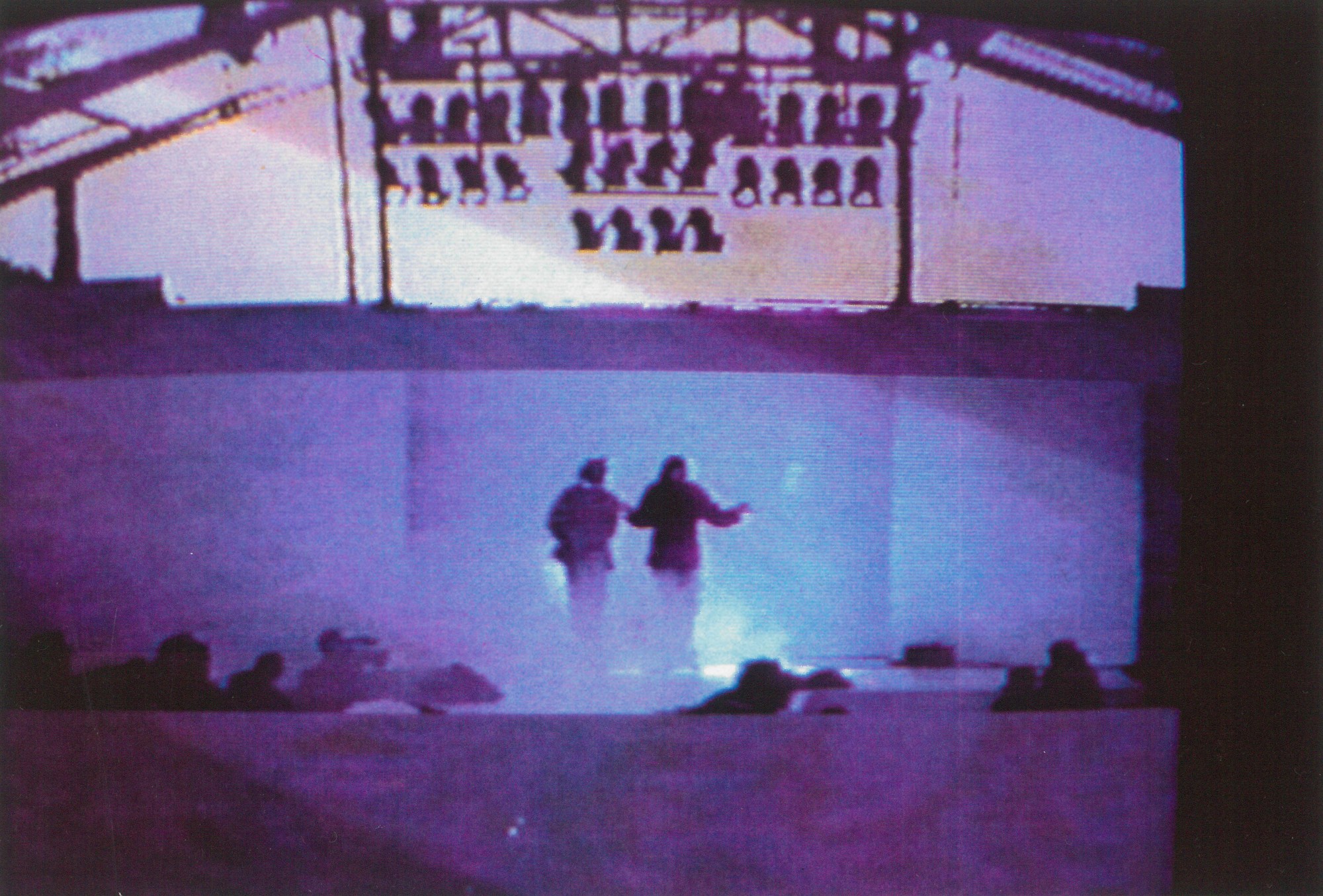

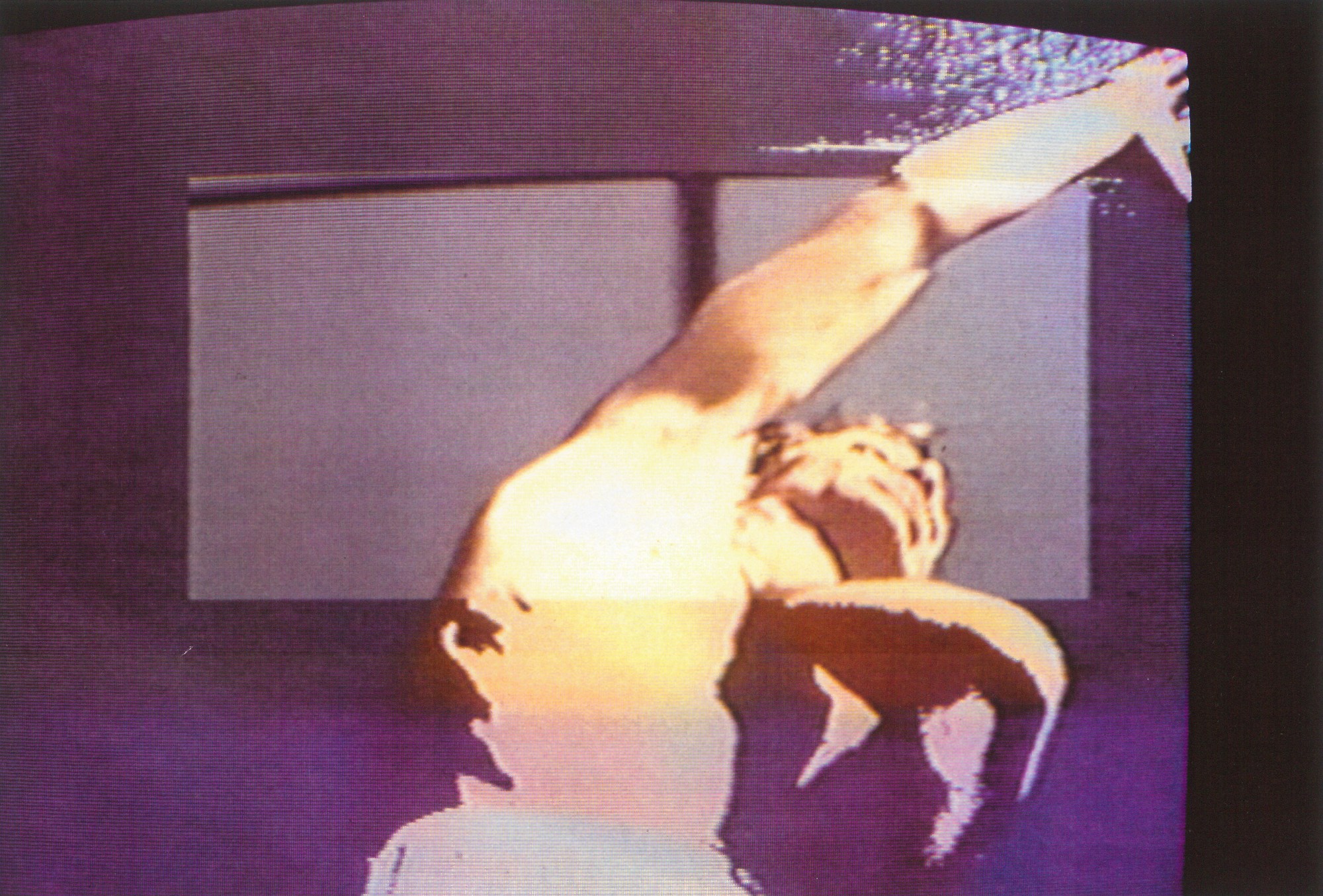

Most alluring, however, was his runway show presented at 6:30pm on the 19th of September: a coalition of performance art and design nous. Instead of models, an audience of German officials and press witnessed two mimes from the Berlin-based Circus Roncalli acting out scenarios that hinted at situations involving work and leisure. “My father hated catwalks and never wanted to do one,” Lorenzo Osti, Massimo’s son who is now President of C.P. Company, explains. “But doing one was a condition [from the West Berlin Senate] so the idea was, ‘How can I do it differently? Let’s try to change everything I can change.’”

The array of clothing put on show was just as unusual. Garments from Osti’s three most prominent sportswear brands, C.P. Company, Stone Island and Boneville, all appeared on stage together. For fans of C.P. Company and Stone Island today, it might seem unusual that these two labels would appear side-by-side (as well as the now defunct Boneville) but Osti, who passed away in 2005, approached his labels as though they were each a part of one wider sartorial vision. “Everything started in my father’s head, in my father’s studio,” Lorenzo explains, “and only after something [was designed] was it falling to one of the brands.”

Having had no formal fashion education, Massimo Osti approached his work like a graphic designer. For example, Osti created garments not by constructing toiles like many are trained to do, but by using a Xerox machine to photocopy garments he had sourced for research. He would print these out and pin them to other research garments to create his designs, creating Frankenstein monsters of paper and fabric. The clothing he created borrowed details from workwear and military uniforms, which were readily available on the secondhand market. He became well-known for the groundbreaking fabric developments his company created with specialist factories in Italy and Japan.

He added elements to natural materials to make them more hardy, such as his creation of Raso Gommato – a military grade cotton coated with a layer of polyurethane to make the material waterproof and windproof – and Rubber Flax and Rubber Wool, where the fabric was sprayed with a waterproof layer of rubber. Garment dyeing, his most well-known and revered development, was a process by which an entire piece of clothing would be dyed after it was constructed, creating an effect that looked as though it had been well-worn even when it was brand new. The thermosensitive fabric of the Ice Jacket, designed for Stone Island in 1989, is still one of the designer’s most covetable garments on the resale market, 36 years since it was initially designed. Its most famous iteration – in a woodland camouflage pattern – can cost up to £1500.

The environment within his studio was completely different, too. In order to freely experiment with all these innovative design methods, his workspace acted more like a laboratory. “We did almost all experiments in-house,” says Lorenzino Piazzi, a researcher and designer who worked with Osti from 1975 until the 1990s, developing many of these innovations. “In the factory there were showers, a dyeing section, a print section, a knit section. I designed one garment in the morning, and the morning of the day after I saw the piece.” The now-iconic Ideas from Massimo Osti labelling on C.P. Company pieces from the 70s, 80s and early 90s were a nod to this freewheeling form of experimentation.

“This is a person who had little to do with fashion,” Moreno Ferrari, designer for C.P. Company from 1996–2001, explains. Fashion with a capital ‘F’, that is. In Italian fashion terms, the 80s was the age of Armani, Versace and Moschino, all based out of Milan. For both women and men, silhouettes were replete with boxy shoulders and nipped waists. Osti, who lived and worked in Bologna his entire life, designed clothes with relaxed forms, such as baggy shell-like outerwear that was intentionally oversized and jumpers that were wider than they were long. He was guided by the philosophy that clothing should be comfortable and functional.

As the legendary sci-fi writer William Gibson, a long-time fan of Osti’s work, wrote in his introduction to the book Ideas From Massimo Osti, he catered to men “for whom ‘dressing down’ was a genuinely radical gesture.” For Gibson, his work indicated “a refusal to play a crucial game. Rumpled. Death to shoulder-pads, cufflinks, loafers trimmed with bridle-hardware.” Osti rejected the old world of suits, shirts and dress shoes in favour of clothing imbued with a sense of liberation. “My objective,” Osti stated in a 1991 interview with fashion trade rag Gap Italia, “is the dilation of the concept of ‘free time,’ of extending it, at least in clothing, into the working hours of the day.”

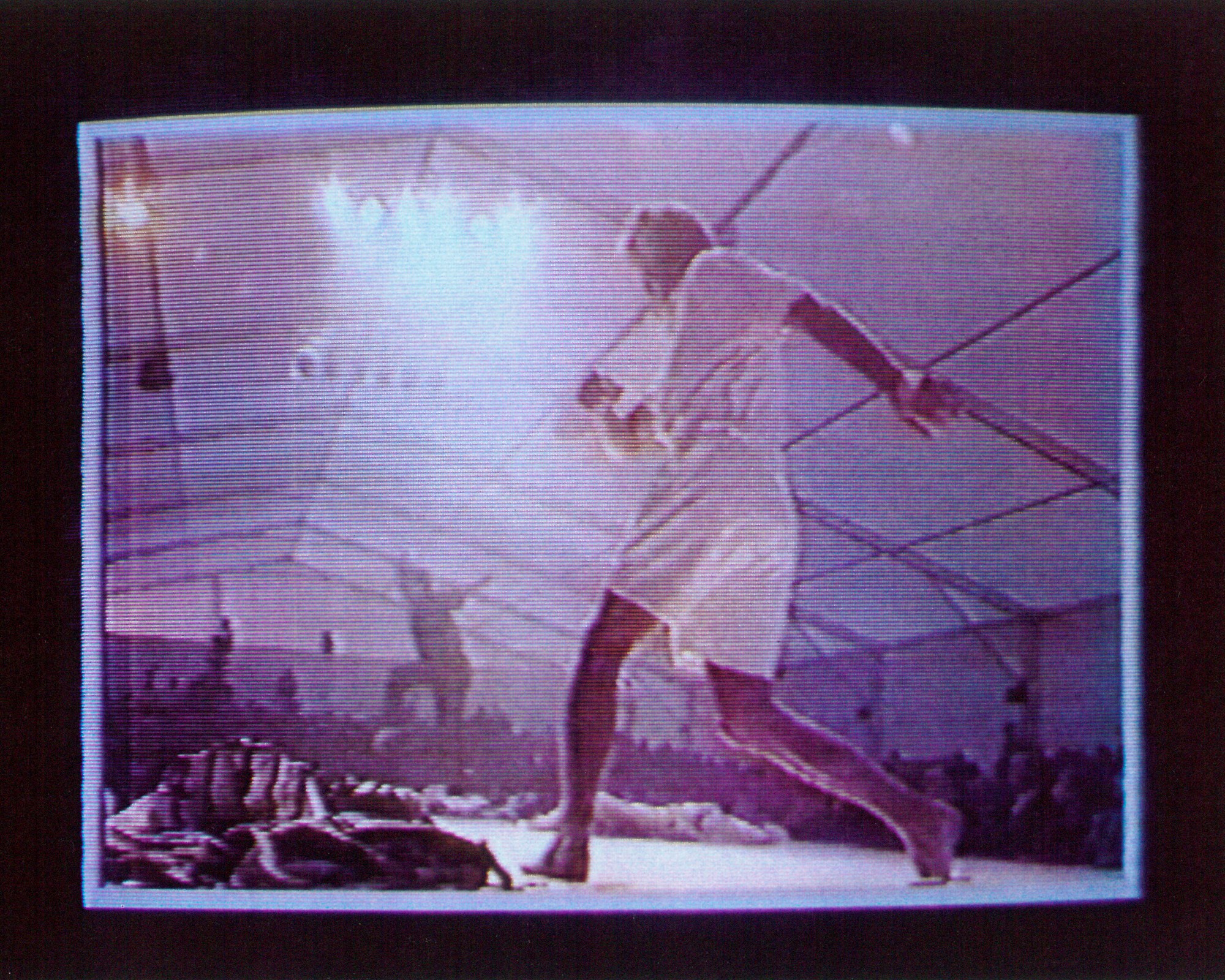

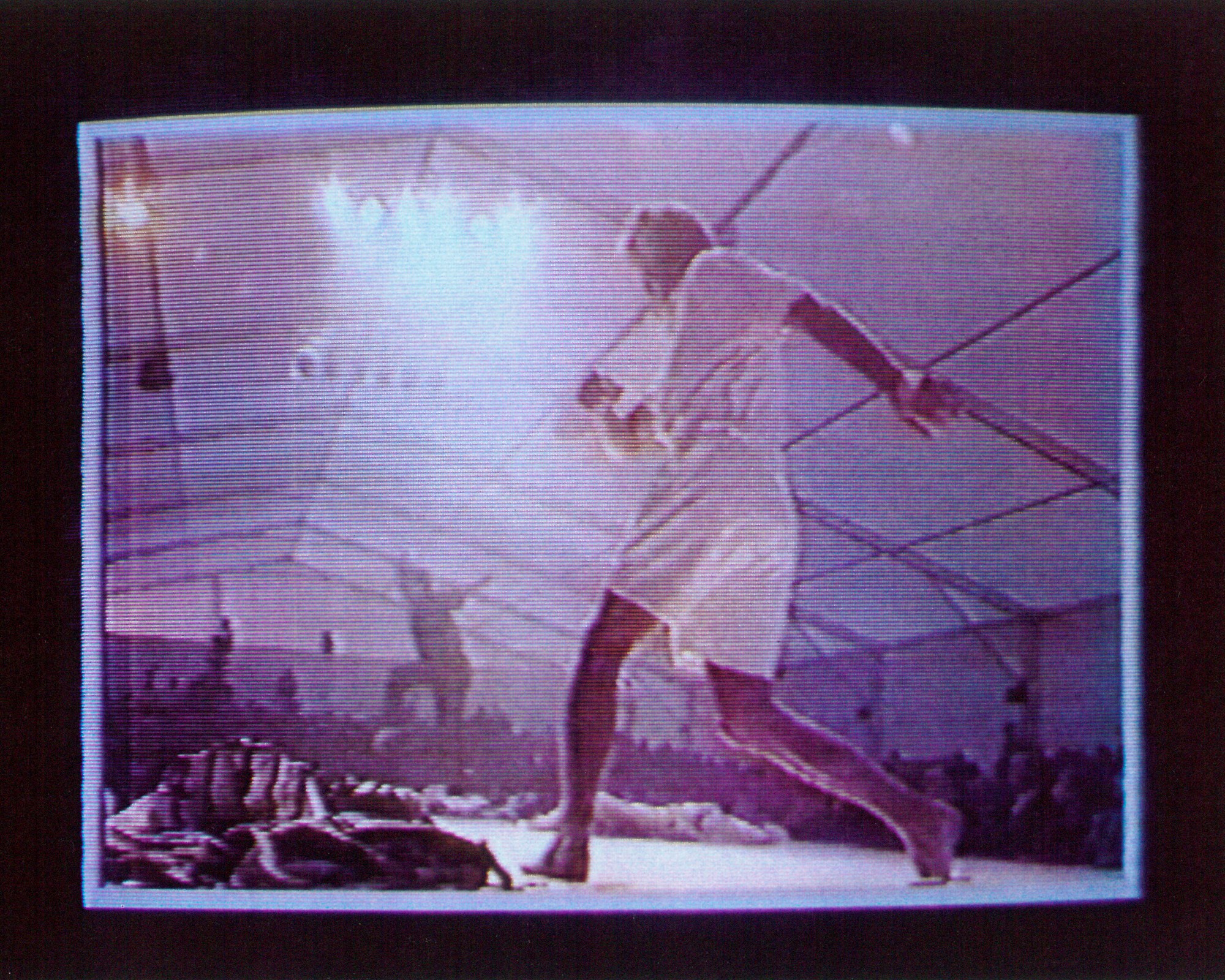

The Berlin show was a effort to communicate this ethos. In the performance, viewable in the last six minutes of this video, men encounter different scenarios in nature, such as braving a storm and swimming in the sea. At one point the sound of a helicopter prompts the performers to act, rather comically, like soldiers. The performers stand to attention — one wearing a C.P. Company coat based on a hunting jacket and the other in the brand’s legendary Goggle Jacket — then mime fighting with swords. They then before dropping to the floor to act like snipers hiding in the long grass. The soundtrack of rolling synths suddenly comes back, and, as though they have been released from their service by this aural shift, the men begin to dance. “It’s sort of an imaginary background to the collections,” explains Agata Osti, the designer’s daughter, and the manager of his extensive archive in Bologna. “Because, of course, the clothes were meant to be worn in the city – so you have the city sounds, but you hear the sounds of the sea, of the wind.”

“He was not interested in showing his products,” says Renato De Maria, a filmmaker who accompanied Osti to Berlin to document the trip. “He wanted the show to be a kind of philosophy of life.” At one point, the performers mime a game of tennis – a reference to an absurd tennis playing scene in the 1966 Antonioni film Blow-Up, which depicts a fashion photographer’s experience of London in the Swinging Sixties as a strange, hallucinatory time and place. “The show is fearlessly experimental,” explains Robert Newman, a long-time admirer of Osti’s work and Head of Design for Massimo Osti Studio. “But there’s a lightheartedness to it, which I think we miss nowadays in the world of sportswear. It wasn’t grotesque, it wasn’t macho – it was cartoonish.”

Born in Bologna in 1944, Osti started his career as a graphic designer in the 60s, launching his first label Chomp Chomp in 1969, a line of T-shirts whose logo and prints drew on the aesthetics of comic books. He founded his first sportswear brand, Chester Perry, in 1971, which would be renamed to C.P. Company in 1978. Bologna’s creative scene in the 70s was highly influential to the designer. The University of Bologna drew thousands of young students to the city and was home to the legendary art, music and theatre school DAMS (Discipline delle Arti, della Musica e dello Spettacolo) at which the philosopher Umberto Eco was a professor. Around the school, there was an explosive underground art scene, characterised by experimental performance and radical comic book illustration pioneered by artists such as Andrea Pazienza.

“Bologna was very, very alive,” Piazzi, who grew up in the city, explains. In 1967, when Osti was in his early 20s, the Italian student movement began to percolate through Italy, which demanded a copmplete cultural and political revolution. In 1969, leaders of the student movement formed an alliance with striking factory workers, giving rise to the anarcho-communist movement Autonomia Operaia in the 70s. Osti came of age in a place that was steeped in a sense of burgeoning revolution. “He loved Bologna,” Ferrari, a fellow Bolognese, explains. “Bologna in those times was 100 times more advanced than Milan politically and culturally – Bologna was the world.”

“He was not interested in showing his products, he wanted the show to be a philosophy of life”

Renato De Maria

“It’s impossible that all of this didn’t influence his soul, his mind,” De Maria, who was involved in the student movement as a teenager, explains. He met Osti in 1987 when he was just 25 years old and was promptly invited on the trip to Berlin to document their experience. De Maria had recently paid a visit to Berlin and traversed the streets with his friend Wim Wenders, whose film Wings of Desire, following an angel who watches over the inhabitants of the divided city, had been released earlier that year.

“There was still the memory of the war,” De Maria explains, “and there was still a war [going on] at the time.” The dark haze of the Second World War still hung over the city through the spectral shapes of bombed out architecture and the remnants of abandoned industrial space. It was the Cold War, however, that defined the city’s character. In 1987, the city was still divided by the Berlin Wall, which had been constructed in 1961 to create a firm border between the Communist GDR and capitalist Republic of Germany. A press note dated to the 26th September, just after the show, highlights the particular interest Osti had in visiting Berlin: “The reasons for Massimo Osti’s presence in the city, which is the heart of Europe and a symbol of the contradictions of our time, lie not only in the uniqueness of his technical work but especially in the particular ‘history’ of the C.P. product.”

“Our family has always been into politics,” explains Lorenzo, “and being in the centre of these colliding two words was definitely important to my father.” The show itself may well have been a jab at the West German government. A long-time leftist, who eventually served on the Bologna council for the PDS – an outgrowth of the Italian Communist Party – he was fascinated by the Eastern side of the Berlin Wall. “Treating garments like someone in a workshop would treat their boiler suit in front of a load of people in government, there’s some sort of gesture there, right?” Newman laughs.

Ambiguity, however, was a characteristic of camera-shy Osti’s career. The original name for C.P. Company, ‘Chester Perry’, was adopted from the fictional factory where the hero of Frank Dickens’ comic-strip Bristow works, a place where no-one knows what is being produced and all employees try to do as little as possible. This was hardly the experience of workers in his studio in Bologna – or himself, a man who was a famously hard worker. But it is the legend created around his work that matters: the ethos his Berlin show tried to communicate. “There’s a utopian ideal in that show, and in that entire universe,” Newman says. “I think the context of showing it in and to the government was a real manifesto like, ‘this is how people should live.’”

Really, what Osti did with this show was radical. Fashion shows at the time predominantly followed a classic format: models walking up and down the runway showing off the new season. What Osti was doing was more akin to what designers such as Bodymap, who worked with dancer and choreographer Michael Clark on their runway presentations, were pioneering in London. While there has been much attention paid to the explosion of avant-garde fashion in 80s London, Bologna as a site of radical fashion has largely been left out of the history books.

When we think of Stone Island or C.P. Company today, we think of the durable materials, technical know-how and well-placed buttons and zips. But this show proves that the garments weren’t everything. When Newman joined Massimo Osti Studio in November 2022, Agata insisted he familiarise himself not just with the archive of garments designed by Osti, but the other forms of media he experimented with in his career, such as video and graphic design. “The show gives us a glimpse of [his work] in a much more expanded context,” says Newman, “what that guy was really thinking about when he was putting zips and buttons on jackets.”

Although his work had a subversive, political edge, they were, like all fashionable garments, still clothes that had to be sold. Perhaps the most fitting metaphor for the show lies in Lorenzino Piazzi’s description of the garments themselves. “The clothes, they give the sensation of freedom, of revolution,” he says, “but the products often did not contain any real functionality, but a fantastic aesthetic effect.”

Text: Eilidh Duffy

Translator: Sara Quattrocchi Febles