“What are some of your earliest memories? What images or smells do you associate with it? How do you define the future? How is it similar or different from how your family or your community defines it?”

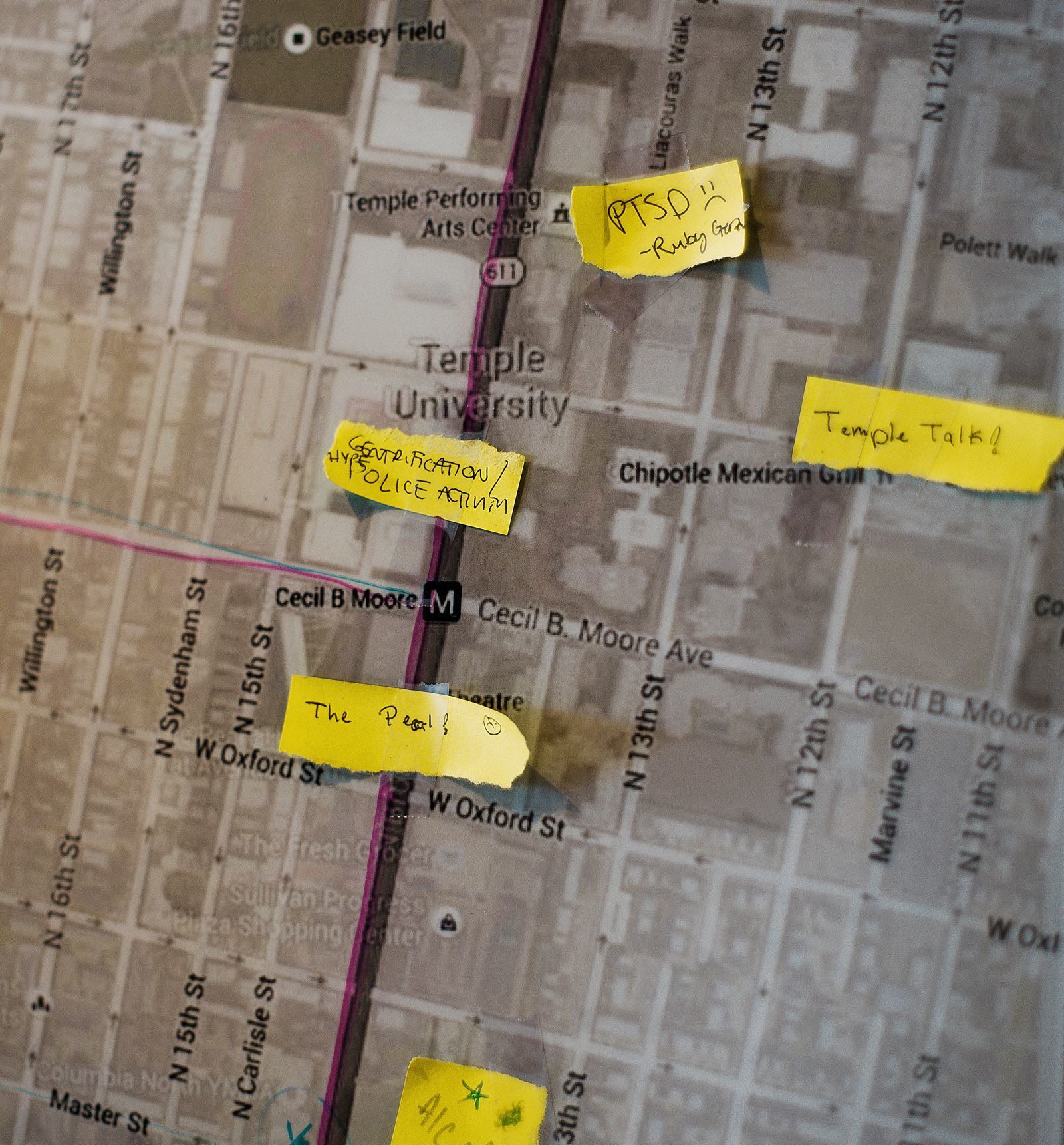

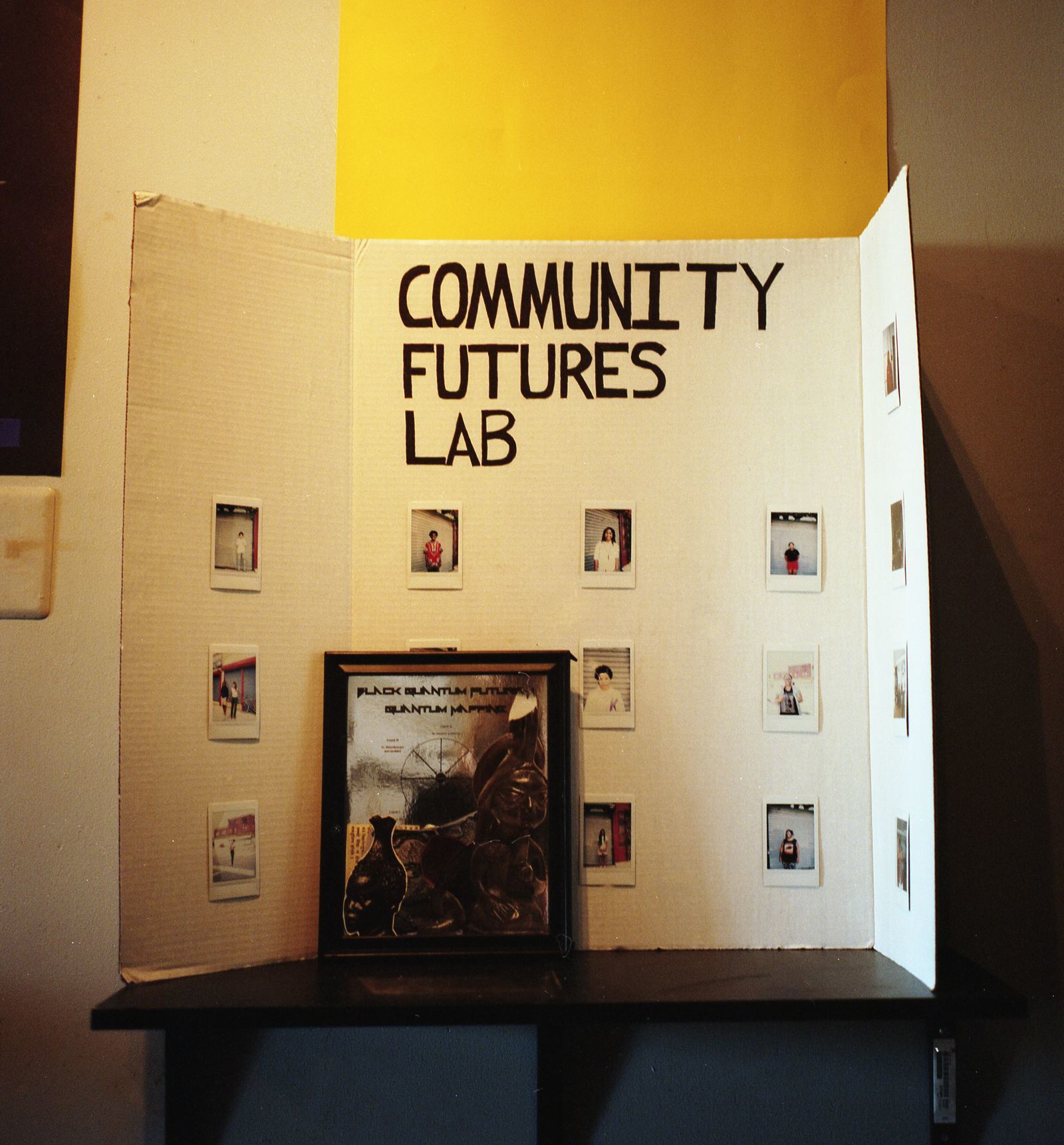

These are some of the questions on a survey about time and memory at the Community Futures Lab in North Philadelphia. Put in these terms, time travel ceases to be farfetched and reveals itself to be something we engage with every day — in memories and dreams and aspirations, in seasons and holidays and routines. As the surrounding community is displaced by gentrification, Community Futures Lab uses time travel and Afrofuturism (an aesthetic that applies sci-fi and technoculture to African diasporic experiences and imaginaries) to preserve community memory and envision generative futures.

The Lab’s co-founders, Camae Ayewa and Rasheedah Phillips, have long used Afrofuturism and time as lenses for their art and activism. Ayewa, who makes music as Moor Mother, is currently touring on her critically-acclaimed debut full-length Fetish Bones, a noise-poetry-punk-jazz masterpiece. For nearly a decade, Ayewa has co-booked ROCKERS!, a monthly show series that features queer, trans, POC, and femme artists. Meanwhile, Phillips — a sci-fi writer, mother, and full-time housing lawyer — was booking charity balls under the name Afrofuturist Affair as a way to celebrate Afrofuturism and connect its creators with one another. “Afrofuturism was very much an academic term,” Phillips says, “but also used in underground spaces. I was interested in the practical aspects of it and how it could be used in communities and for the people that I work with as an attorney.”

Having begun to collaborate when Ayewa made a soundscape for Phillip’s debut novel, the pair’s involvement eventually evolved into Community Futures Lab. As with many former manufacturing centers in America, North Philadelphia was gutted by national industrial collapse and white flight, and largely ignored by the city until it was targeted as a site for a multi-million dollar redevelopment plan that is already uprooting the current community. Ayewa is from Maryland and Phillips is from New Jersey, but both have called North Philadelphia home for over a decade and emphasize their ties to the area. With only a year-long lease, the Lab can’t prevent gentrification, but it does hope to stage a sort of intervention by hosting workshops on issues such as tenants’s rights and mental health in black communities. They’re also interested in documenting community memory and creating a quantum time capsule meant to be accessible across time, rather than just in a distant future.

On a sunny Tuesday in winter, the multicolored buildings along Ridge Avenue are glowing, the Lab is preparing for the Sixth Afrofuturist Affair charity ball, and Ayewa is getting ready to go coach varsity basketball. We catch up to talk about the Lab, time travel, housing, and working within a community while also being expansive.

What is the relationship between some of your other collectives (Metropolarity, Black Quantum Futurism, Afrofuturist Affair) and Community Futures Lab?

Rasheedah Phillips: Community Futures Lab is the natural evolution of [those principles] — us putting into practice in a particular embedded community, these principles of Afrofuturism, and black quantum futurism and using it as this liberatory tool. And using art and music. We don’t see those things as separate — they’re just ways of living and experiencing the world and empowering people. I mean, we don’t think we empower people, I hate that concept. We’re in a community.

We live in this community and we’ve been watching and experiencing what’s happening in terms of gentrification and redevelopment. We wanted to have a space where we could think about it and theorize with the community around what we’re going to do and how we’re going to seek change, and bring or create this future that we all collectively want to see.

So much of this project about preserving community memory. How has the community interfaced with that idea?

RP: It’s a popular idea. It sounds cool, but that’s to the choir of people who are engaged with this stuff already. When we do a workshop we get a lot of people from outside of the community. It’s harder to get people from the community to come — one, because they’re getting displaced, two, they have to evaluate coming to this workshop over going to work or having this hard day and wanting to go home and go to sleep. It’s a lot more difficult and challenging.

We’re getting written about now, that’s awesome, but I don’t think it’s yet changing perception around the people who are being affected by this displacement. That’s a very long term process. It’s not something that we can do in six months just by having a bright storefront.

Looking at this schedule, there are tenant’s rights workshop, domestic violence workshops. You’re doing work on a multitude of levels.

Camae Ayewa: Yeah and we change them up, so these are the workshops we’re doing now for winter. Wintertime — slum landlords, people are cold, things are getting cut off, things are not properly fixed. But we’ve [also] done stuff from creative writing to just talking about music.

RP: The lens of the project is housing. And housing is the most important stabilizing factor for people individually and for communities. If the housing situations aren’t proper then nothing is proper, really. So talking about housing experiences gets at how people [and communities] experience time. This community is being displaced and [developers are] building housing but that housing is not necessarily going to be for [the community].

CA: We want everyone to understand that where you have lived and the times you have moved impacts how you are and what you’re able to bring to the place you are now.

I went back to somewhere I haven’t been in a long time and realized one of the most familiar things was the quality of the light. I’d never counted that as a sense before.

CA: I came to school here in the fall, so whenever it’s fall here I’m like, “Ohhh, this!” Everything that’s happening — the smell, where the wind is — takes me back to coming here for the first time. I feel like that’s what people are trying to investigate.

We also participate in the erasure of our own memories, of being able to not care, or being able to find ways to cut ourselves off. I feel like we need to do that investigation in ourselves more.

Currently, so much attention is given to “pop feminism,” feminism really rooted in being young. It’s so important to emphasise the intergenerational issues.

CA: Yeah. [If you’re just looking at] black Twitter, they don’t speak about the actual situations that black women are going through. You would think that we’re just mad about a publication not doing the right thing or something.

[For example] we talk about underreporting because of what can happen with the police — there are so many examples of losing your home because you call the police too much.

What are some things you’re excited about in the future?

CA: In March we’re having an exhibit at the Kelly Writers House connected to the University of Pennsylvania. In February, BQF will be taking part in Transmediale festival in Berlin. This weekend there’s the Afrofuturist Affair charity ball [for the six year anniversary]. We’re still doing events but in a way that’s not so draining of us and that we can expand and can reach more people besides these artist kids that are afraid to come to North Philly.

RP: We’ve gotten so many more resources from co-curating, even though for me it sometimes feels like selling out. But I get so much more support if I go over to Berlin and Rotterdam and do some sort of Afrofuturism fest than I would in my own city.

CA: On my last two tours I’ve seen… They don’t want us in Portland. They don’t want us overseas. But we are overseas. And that’s the whole idea… moor is another word for black. Black people weren’t just brought on some slave ships to America and that’s how we started. We’ve been to America before Christopher Columbus. We were in Brazil before conquistadors. All over the world. I don’t know, it may seem like a sellout to somebody but this is expansive! We can’t just change North Philly with one storefront in six months. But we can expand the idea of what North Philly is.

Credits

Text Nina Mashurova

Photography Tonje Thilesen