2015 was a landmark year in critical conversations concerning black culture. This year, we entered into a greater dialogue about cultural appropriation and clarified why it’s not ok. We saw the growth and progression of #BlackLivesMatter and debated why #AllLivesMatter undermines the movement. In fashion, we witnessed the rise of Grace Wales Bonner and celebrated natural black hair back on the runway. But even in 2015, there’s still a long way to go. Photographer Ronan McKenzie aims to take another step towards normalizing the black figure in her exhibition, A Black Body.

Ronan may have been born and raised in the multi-cultural hub that is East London’s Walthamstow, but the reactions she received towards her skin color and dreadlocks led her to delve deeper into her heritage, only spurred on by the lack of ethnic models for her to shoot. We caught up with Ronan before Thursday’s opening to chat black hair, black bodies, and dating white boys as a black girl.

This show explores society’s perception of the black figure in terms of sexuality, prejudice and power. What are your own experiences with this cultural perception?

Although London is insanely diverse and multicultural, that doesn’t necessarily mean everyone understands and is comfortable with everyone else’s culture. In my opinion, the black figure is completely over-sexualized both for men and women. The idea of the black male is that he’s strong, powerful, big, muscular and has a big… haha. Which isn’t a bad thing, necessarily; it’s amazing to see more black actors getting great prominent parts like Idris Elba and Adrian Lester. It’s just a shame that for black and many other ethnic minority males, it’s either that or the ‘token’ role. Black women on TV are mainly curvaceous, bolshy and independent like Queen Latifah and Missy Elliott which, again, is great. It’s just a shame that those are the only situations in which black women are seen to be powerful, in my opinion. You rarely hear about black power — excluding in the civil rights movement, and at school even that part was skimmed over — the main thing we were taught about was slavery, not powerful black writers, creatives or professionals.

Even though I grew up in a multicultural environment, my idea of what was beautiful or sexy was looking European — straight hair, lighter skin, slimmer features, because that’s all I saw. When I got a bit older, I became comfortable being who I was. I grew locs and embraced that. Even though I literally can’t go anywhere without someone — of any race — calling me a Rasta, I’m comfortable with myself. When I started dating, for some reason the majority of them were white English, and every single one of them — except my boyfriend now — at some point said something like “You’re so approachable for a black girl,” ” You’re so exotic!” or “You’re the first black girl I’ve been attracted to!” In their eyes, these words were supposed to be compliments, but it’s so backwards and almost offensive that I was only seen as attractive because I spoke, looked, or dressed in a way that these white guys could relate to, not because of who I actually am.

I think if you’re black, you’ve had a situation at some point in your life in which you’ve been the only black person that you can see. You feel that you’re different. Even at school, my mom was always worried that my brother would be perceived in a negative way because he’s a young black boy. Statistics show that young black males are more likely to be stopped and searched than any other race. How is that supposed to make you feel, as a young black person, knowing that racism and prejudice are institutionalized and seen as the norm?

Are there any specific examples in the media that sparked you to start this project?

I’ve always been interested in finding out more about my black culture and heritage. As I was getting more involved in fashion from a photographer’s point of view, looking for models to shoot who are of ethnic minorities was becoming ridiculous. In my experience of looking for models, most London agencies have about 1-4 black girls, who either look white with brown skin or are the epitome of Africa — wide features, blacker than black skin and a shaved head — both of which are absolutely beautiful. But there’s just no in between. There are hardly any East African or Kenyan with Indian heritage girls, with natural hair.

What do you want to show or say about black identity in your exhibition?

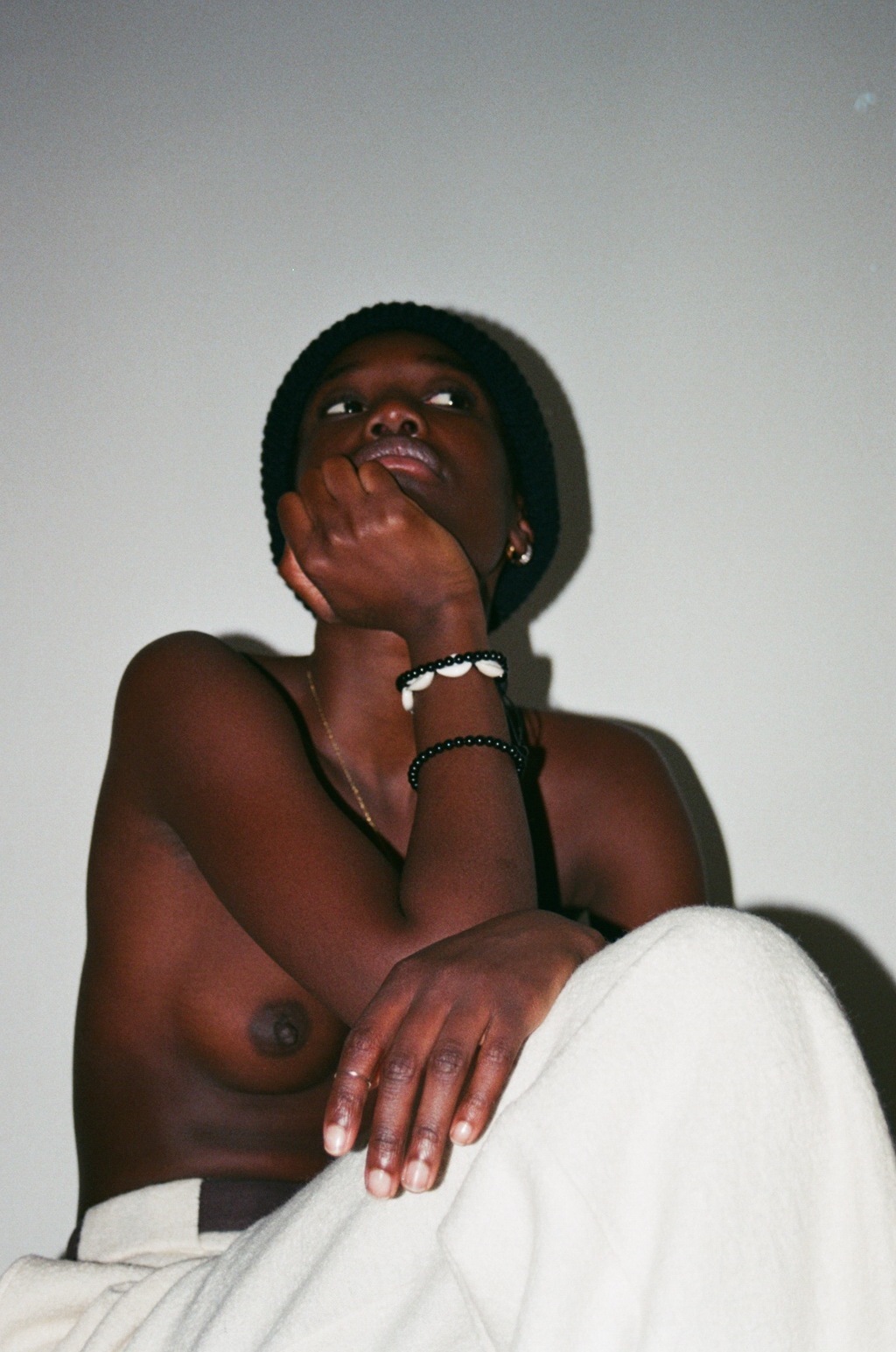

I want to show that black identity is as diverse as our skin tones. It’s so important to be comfortable with who we are as black people in a society where black people are still looked down on in some situations, and be proud of who we are and certain about what we do. Within my exhibition, I don’t want to assume anything about the people I shot, I just want the images to speak for themselves. For example: I shot this amazing guy, Wilson, and I was going to put him in a suit. At the last minute, I asked him how he’d feel about wearing one of Marie Yat’s beautiful rib dresses. He just said, “I’ve never worn a dress before, but sure I’ll give it a go.” For me the images we created aren’t about Wilson looking gay — or Wilson wearing a dress at all — it’s about the power that he exerts through just being himself and feeling comfortable in who he is. He makes the outfit he’s wearing or situation he’s in almost irrelevant, and that’s what’s important about black identity to me.

How does gender affect how we perceive the black body?

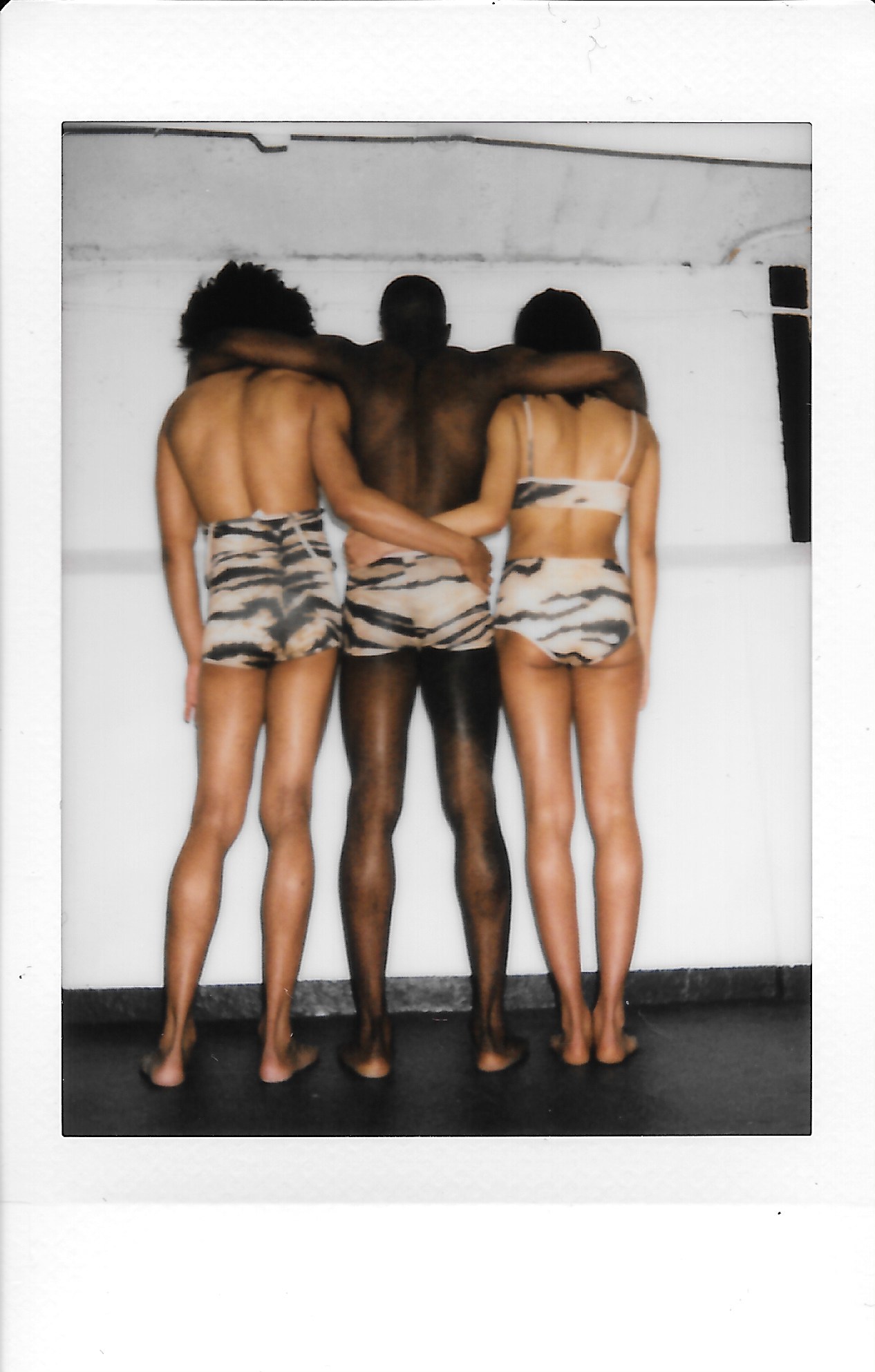

When I talk about the black body I mean it as our actual bodies as well as the body of the black community. I think perceptions of the black body — both physically and as a community — depend more on your own personal experiences rather than on gender. For example, when I started secondary school, I got asked by a white classmate what color my nipples were — she’d never seen a black person naked. This comes from all of the books you have when you’re a kid, in my experience, most children’s books were all illustrations of white people. Diagrams of the physical body included were only of white people, so something as small and irrelevant as the color of nipples was unknown to people who’d never seen a physical naked black figure before.

How do you think perception of the black body has changed in recent years?

Black people have been in the media much more than they were 10, or even five years ago, which has an affect on the general perception of the black body. The more people who see the black body, the more normal it becomes and the more people see black people as equals.

What about in fashion?

I’m so happy to see Grace Wales Bonner doing so well and sticking so firmly to her positive afrocentrism. The shoot that Harley Weir and Julia Sarr-Jamois did with Wales Bonner was just beyond words, as are Grace’s presentations. And it’s incredible to see Lineisy Montero with her beautiful natural hair doing so well in fashion, but I still feel that fashion has a long way to go in terms of not only accepting black people, but other ethnic minorities, too. I was thinking about actually starting up my own agency to showcase these beautiful people that hardly exist in fashion in London. Most black models still have a weave or wig to have straight hair, not only because it’s seen as more desirable, but so that hair stylists don’t damage their natural hair because they don’t actually know how to work with it! The perception of the black body is definitely changing, slowly but surely. The demand needs to come from way higher up though. If big brands and designers thought that their sales would still flourish by using a more diverse range of models, they would. Then modeling agencies and casting agents would be forced to sign more culturally diverse models because there would be a demand for them. Unfortunately, that’s not the case at the moment.

What are the differences between our conscious and subconscious perceptions?

To me, conscious perceptions are perceptions that we create ourselves, subconscious perceptions are ones that have been engrained in us that we don’t always know we have or agree with. For example, I was watching Reggie Yates’ new documentary on homophobia within black and Asian communities. One homosexual black girl said that homophobia had been engrained in her since she was so young, that even though she’s come out as a lesbian, she still feels uncomfortable or negative thoughts when she sees a gay couple kissing. That’s a subconscious perception.

How did you cast the people in your photographs?

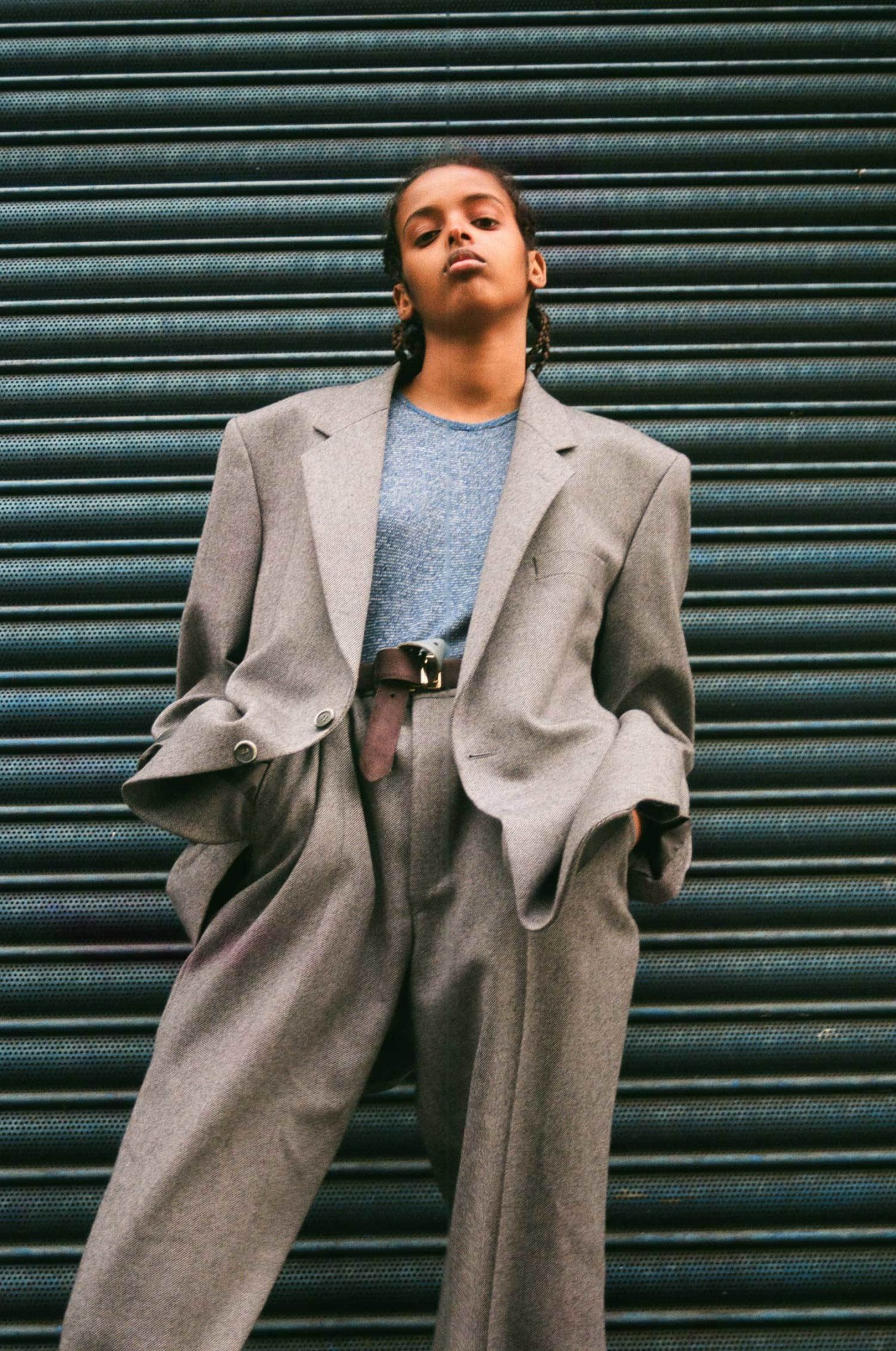

This specific project was really exciting because I could shoot exactly who I wanted to. I got to shoot my mom, which I absolutely love doing, and some of my friends which makes it so much more personal. A lot of the people are models; I shot an amazing Somalian girl, Hamda, I shot the beautiful Poppy Okotcha three times. There were a few people that I just found on Instagram, and I also took some random photos of people out in Camden one night. So it’s a big culmination in loads of ways, really.

Who styled the portraits and what were the reference points?

I styled everything for this myself, and it was important for me that the designers that I pulled from were interested in the topic. I emailed all the designers directly before contacting PRs to make sure that they were down for the project and I got such an amazing response! I also love shooting pieces from new designers; within the exhibition, I shot pieces from Mark Glasgow, Marie Yat, Amy Crookes and Kate Zelenstova who all create super cool and intricate pieces!

Is this a topic you want to explore further?

Definitely, researching and creating for this exhibition has only made me more interested in representations of the black body in contemporary society. It’s also made me think more about what I can do to make perceptions of black people more positive and the amazing things that black people do in society more widely known.

What are you working on next?

There are a few things that I’m working on at the moment; at the exhibition, there’ll also be the launch of two zines I’m making, one called Meninas — which is ‘girls’ in Portuguese — and one called Strangers. They’re both ongoing projects that I’ve been working on for a while, so I’m excited to continue those and hopefully turn them into regular print zines. Maybe I’ll start up that modeling agency, too.

A Black Body is open December 17 – 20th at Doomed Gallery, Dalston.

Credits

Text Felicity Kinsella

Photography Ronan McKenzie