“Most people, when they see my work, assume that I’m a man,” Esmaa Mohamoud says pensively when we meet at NADA art fair in Miami, where she recently showed her work for the first time in the U.S. “My perspective comes from my own masculinity. Even though I am a woman, I am masculine as well.”

At 25, the Toronto-based artist has quickly arrived at the forefront of the contemporary Canadian art scene with her evocative, multimedia installations at the intersection of race, gender, and athleticism. Her concrete sculptures of basketballs, in conversation with her sophisticated performance-based photography, draw simple yet ambivalent narratives around blackness, challenging its mass-mediated iconography. “I’m interested in how we perform gender within race,” says the artist, who lists David Hammons and Richard Serra as key inspirations, “and I’ve been using athleticism as a way to enter within this.”

Sports culture played an important role in Esmaa’s upbringing. She describes it as a “place of community.” But as she grew older and saw her (mostly male) friends getting college scholarships to play basketball or football, she became conscious of how the politics of athleticism and education can operate in America: “Without these sport-related opportunities, they wouldn’t be able to attend post secondary [education],” she explains. “That was a scary reality for many young black people.”

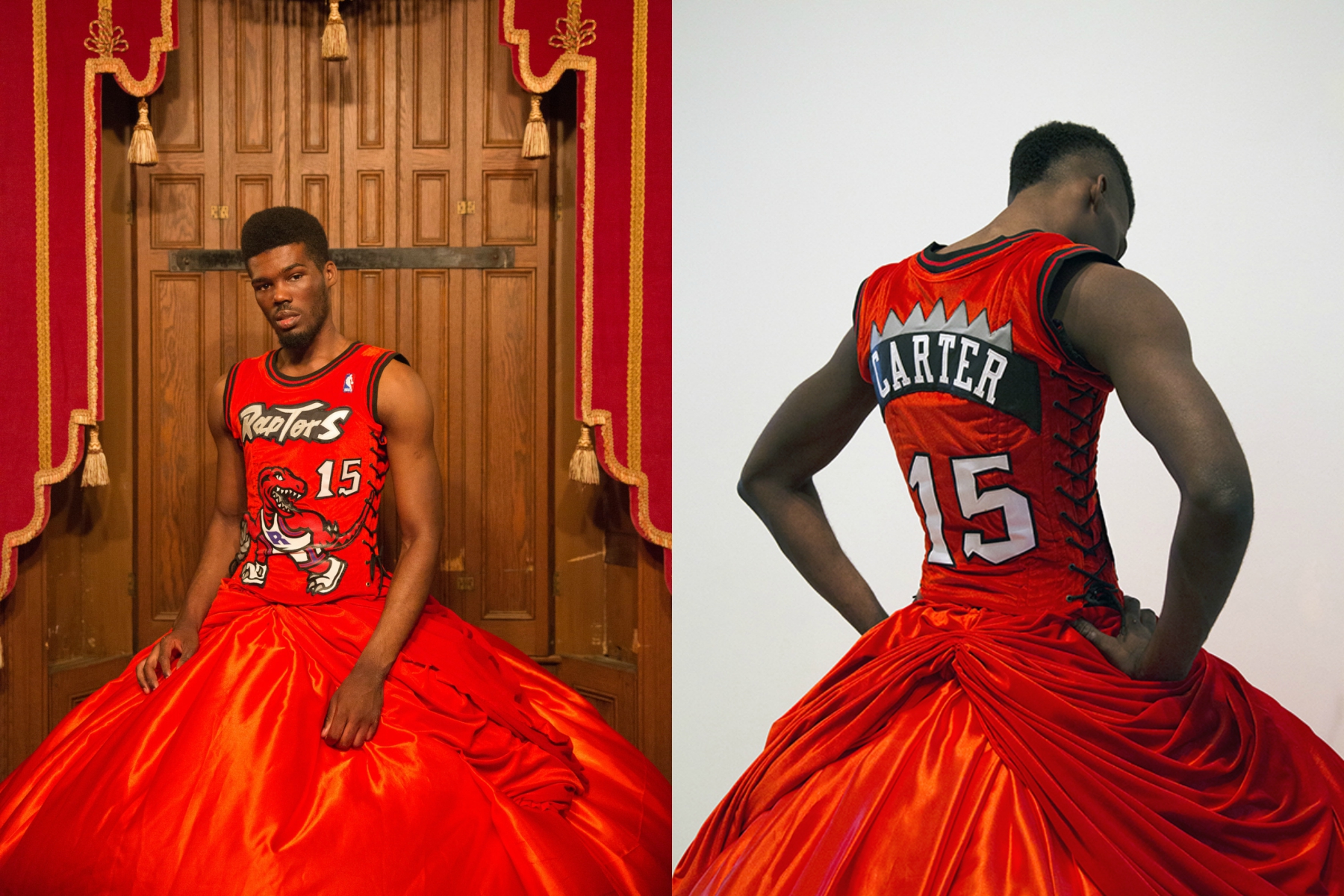

For her multimedia series One of the Boys, Esmaa recruited two muses to wear a hybrid garment (designed in collaboration with artist Qendrim Hoti) made out of a basketball jersey that morphs into a flamboyant, bouffant ball gown from hips down. Two of the resulting photographs (which were on show in Miami) portray a black model viewed from behind. Esmaa tells me that the subject in the purple dress is female, after I incorrectly assume they were both men. “That’s part of why they’re shot in this position,” the artist explains, “it’s so you play with the ambiguity of gender and the assumption of who performs in these realms.”

When I ask who the models are, she smiles: “It was actually quite hard to find a black man who was willing to put on a dress,” she admits. After asking a dozen people — including unwilling fellow artists — her friend’s little brother finally agreed to take up the task. “I find this work important right now, because black masculinity is so fragile that just wearing a garment really alarms a lot of black men,” she says, explaining that she was equally as interested in having those conversations as she was in producing the final works.

Esmaa understood fluidity at an early age. But as the only girl of five children, born to immigrant parents with comparatively traditional views, her perception of gender didn’t always match with familial expectations. In fact, the title of her photography series references an early childhood memory: when her mother would demand that she put on a dress before going outside to play, Esmaa’s natural response would be to put on a jersey over the dress. The unimpressed parent then argued that she was not “one of the boys.”

“Here in North America, I find that gender is much more fluid,” says the artist, who grew up in London, Ontario. “I never really felt that I had to present as either a woman or as a man.”

As Canada celebrates its 150th anniversary this year, the discourse around cultural identity — specifically in the context of reconciliation — continues to generate national debate. Over the summer, while Prince Charles was being dragged around Gatineau in a horse-drawn carriage during an official ceremony, a group of indigenous protesters set up a teepee outside of Ottawa’s Parliament Hill in what they described as a reoccupation.

In the cultural sector too, there has been tension. In September of this year, the Art Gallery of Ontario curator Andrew Hunter resigned in protest against what he described as “a deeply problematic and divisive history defined by exclusion and erasure,” which, he said, burdened the institution. The statement dropped a bomb, arriving soon after the AGO had launched Every. Now. Then: Reframing Nationhood — a sort of anti-150th anniversary group show looking at Canada’s alternative national histories, in which Esmaa’s work was featured. (Soon after Hunter left, the museum announced the appointment of its first Indigenous art curator.)

“You need multiple voices, even to discuss collective shared experiences between cultural groups,” affirms Esmaa, reflecting on the representation of minority groups within institutions. Next year, she will be part of the Royal Ontario Museum’s group exhibition Here We Are Here, which celebrates the work of seven contemporary African-Canadian artists. “I think the diversity of blackness within this exhibition is inspiring,” she says, describing the work she’s producing as an afro-centric football-inspired piece and performative sculpture, referencing NFL players’ gesture of “taking a knee.”

In Miami, her work was shown in conjunction with the silk-printed photographs of John Edmonds, portraying young black men in nylon do-rags. He is Esmaa’s senior by only a few years, and he too, is part of a younger generation of artists who are interested in addressing the iconographic significance of the black body — alongside the likes of Tschabalala Self and Diamond Stingily. But Esmaa is wary of how institutional visibility rolls out: “Sometimes, I feel it becomes a tokenization of black contemporary artists,” she says, calling for an increased awareness from artists about how institutions function. “What I find so fascinating about blackness is that it is a multiplicity, and not a monolith. The accountability falls on both the institution, which chooses to represent a monolithic view, but also the artist — it’s not just one or the other.”

‘Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art’ opens on January 27, 2018 at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto. Esmaa Mohamoud’s solo show ‘three-peat’ opens on February 16 at ltd los angeles, Los Angeles.