“Give me time and I’ll give you a revolution,” said the late, great Alexander McQueen. And while his untimely death was a huge loss for the industry, his legacy lives on in fashion, art and the Sarabande Foundation — a refurbished stable block on Regent’s Canal stocked with an inordinate amount of talent. The Foundation, started in 2012, gives support to young artists and designers that is, unfortunately, often hard to come by in the creative industries.

“The increasing prices of studio space is pushing creative talent out of the cities, or at least into its widest reaches,” explains Trino Verkade, founding Trustee of the Foundation. “It’s extremely challenging, you need connections and luck as well as a huge talent.” But a lot of that huge talent comes from people without connections or trust funds. Which where Sarabande comes in — it provides the UK’s top creative talent with scholarships, heavily subsidised studio spaces and industry mentoring.

As well as financial support, the foundation also teaches the business skills that are integral to making it as an artist. Because having a sustainable career in the creative industries isn’t just about a steady hand and an encyclopedic knowledge of the colour wheel. It’s all the mundane things, the things they don’t teach you in art school — from trademarking, to contract writing, and dry legal letters about intellectual property. “The idea,” Trino explains, “is to give creatives concrete business skills that will help them further their careers.”

So how do they choose the lucky few that get to take up residence in the Sarabande building? “We look for passionate and creative people, those who will push boundaries and those that don’t necessarily tread the conventional path,” Trino explains. “In the Sarabande community they are able to inspire each other to achieve much more.”

Not sure if you’ve noticed, but we’re pretty big on family here at i-D. So we caught up with a few of Sarabande’s talented lot to find out what it takes to make it as an artist in London.

Tenant of Culture, studio 1

My practice concerns itself with the question; how do we determine what should be saved, restored, protected and preserved? I studied fashion, but operating mainly in contemporary art I have been forced to take an interdisciplinary position. I’m from the Netherlands. Dutch fashion education is quite concept oriented, as is our design culture, and that has definitely influenced me. Tejo Remy’s Rag Chair (1991) and You Can’t Lay Down Your Memory chest of drawers (1991) are a good examples of up-cycling in a conceptual way that to this day informs my work.

It would be great if my work could make people think differently about processes of inclusion and exclusion. Especially in relation to institutional archives and the objects that have been selected to represent history. I hope people will question what object is used to tell a story and which one has been left out.

Mimi Hope, studio 2

I was lucky in that my parents took me to see a lot of art as a child. I also had a great art education at Camden School for Girls. I’ve always had ideas for artworks so I think I’ve kind of fallen in to it. Artist Ima-Abasi Okon taught me during my Foundation at LCC and set the bar for dreaming big. Then during university, I worked as Tobias Czudej’s assistant at Chewday’s Gallery — one of the best experiences of my life. I also worked for writer and curator Sacha Craddock and I’m lucky enough to call her a friend and mentor. These people were the best training I could have asked for.

I would love to build a complex in Soho with a foundry, metalwork, woodwork, print room, 3D printer, ceramics studio… and a hangout floor for events and socialising, at subsidised rates and for all kinds of artists, designers and makers at all stages of their careers.

John Alexander Skelton, studio 3 and 5

I’m a fashion designer with strong interests in socio-political movements that shape the world we live in. Art should be political without a doubt, it has to be a reaction to the world we live in. Otherwise it’s not relevant.

I’m from York. It’s a very historic city which is especially apparent in the architecture. I feel that being surrounded by this throughout my childhood has subconsciously had a significant effect on my tastes and cultural interests, which naturally follows through into my work. I believe in sourcing as autonomously as possible within the UK, and that with everything I do there is a sense that the human hand has been involved.

The rapid and unreasonable escalation in rent it makes it nearly impossible to find a studio or a place to live that’s not so far out of central London that you may as well not live or work there. It makes it all the more necessary that institutions like Sarabande are available to aid young creatives in the formative stages of their businesses, so they can grow enough while in residence to enable them to afford a studio afterwards.

Mircea Teleaga, studio 4

I was born in Radauti in 1989. It is a very small Twin Peaks kind of town in northern Romania, and I think it has had a great influence on my work.

The things I would like to change about the industry is most of it. Too much to put down in a few sentences. The biggest challenge about being an artist in London is having a secure income. In this respect, Sarabande has been a real lifesaver; I received a full scholarship, being chosen by Dinos Chapman, to study at the Slade. It’s places like Sarabande with their programme and affordable studios that make life much, much easier for emerging artists.

2018 holds three main shows that I will be in: The Dentons Art Prize for which I have been shortlisted, a solo show at Sarabande opening on 10 April and four-person group show at Space K in Korea.

Saelia Aparicio Torinos, studio 6

I am from a secret island; an imaginary place I use to take spiritual shelter whenever I like. Because it is portable, I make all my work from there. Through my art I compare different dimensions of the absurd — the real one in which we live and the fictions I create. I point at how moralism and social conventions could be considered just as arbitrary as the fictions I construct.

I consider my work as a constant work in progress — I see it and treat it like a novel; a parallel world with a narrativity that relates everything. Some of the artworks are the main character, some are the background, some simply add to the psychological texture of it. I want my work to make people feel as if they were teleport to a planet that is inside this one but their perception wasn’t awake to detect it yet.

Harriet Horton, studio 8

I make taxidermy for people who don’t like taxidermy. Currently I’m making taxidermied prawns which will feature in an exciting project with the chef Jackson Boxer. My work isn’t just taxidermy-focused; the use of neon lighting overrides the death element by creating a mood which exists beyond the physical sculpture. I want my work to make people feel emotive… and hopefully romantic.

I’m mostly self-taught. I studied Philosophy and didn’t go to art school which meant I had to go out and discover everything independently, including all the mistakes that came with it. I often skill swap with other artists — I highly recommend doing this! Beyond experience, the biggest factors are motivation, no Plan B and a positive mentality. Then surrounding yourself with others of a similar mindset.

Having subsidised rent is so crucial for newer artists because it ensures your work is never sales-driven. This is one of the many reason I’m so grateful to be in Sarabande. The freedom and support you’re given is incredible.

Kristina Walsh, studio 8

My work is informed by scientific study and uses artistic design to provoke exploration of the body and behaviour. Before pursuing design, I studied Psychology and Art History and I’m sure that growing up in Chicago, with parents who had a passion for science, has influenced my approach.

After finishing my bachelor’s degrees in the USA, I moved to London to pursue a Masters degree in Footwear at the London College of Fashion. There I was given the opportunity to deep dive into my prosthetics-focused thesis, within which I connected with rehabilitation centres, clinicians, and patients in the USA, UK, and Germany and focused on storytelling the experiences some lower-limb amputees face during rehabilitation.

Everyone has diverse mental, emotional, and physical needs, and thoughtful, artistic design has a very real ability to improve those parts of life. I’d like to advance that perspective and support those needs. I just finished a set of rings that advocate reaching out for mental support by coaxing you to hold another person’s hand — another resident in the studios, Castro Smith, has taught me how to polish them!

Castro Smith, studio 9

I knew I wanted to pursue this the moment I exploded from the womb. I was holding a hammer and chisel. God bless you, mam, you wanted me to be a doctor. She’s a typical Filipina ball of fire — it’s said in the scriptures that she can do anything! My dad is from a north east fishing family in Amble — the history and cold coastline there has always been an inspiration. Tim Blanks described my work best for me: “it’s ancient Assyria transported to the future”.

I apprenticed with some of London’s oldest and best craftsmen on Leather Lane. Then I moved to Japan with the Winston Churchill Trust and trained with the best craftsmen in Japan. Then Sarabande gave me a studio. I am a lucky cricket.

I want my work to make people feel like they own it, it’s theirs. I want them to feel like the piece is something special for them and they can hand it down for generations. And the story of making becomes something to tell others or keep to themselves.

Puck Verkade, studio 10

My videos and sculptural installations address concerns of biological and social definitions with regards to cultural identity, gender and sexuality. I find it important that there’s an accessibility to it, and so I use humour and absurdity to draw the viewer into a vortex of multiple considerations. My favourite is when someone’s completely submerged in one of my videos, and then they suddenly burst out into an awkward laughter. Laughing entangles you, it makes you complicit in a way.

When I moved to London, from Holland three years ago, I experienced a surprising culture clash in English social customs, regarding use of language and layers of politeness, which has definitely informed my practice. Like many artists in London, it’s hard for me to make ends meet here. It seems a never ending loop but I am fortunate enough to have a subsidised studio at Sarabande Foundation, without which I would be unlikely I would be able to afford to keep working in London.

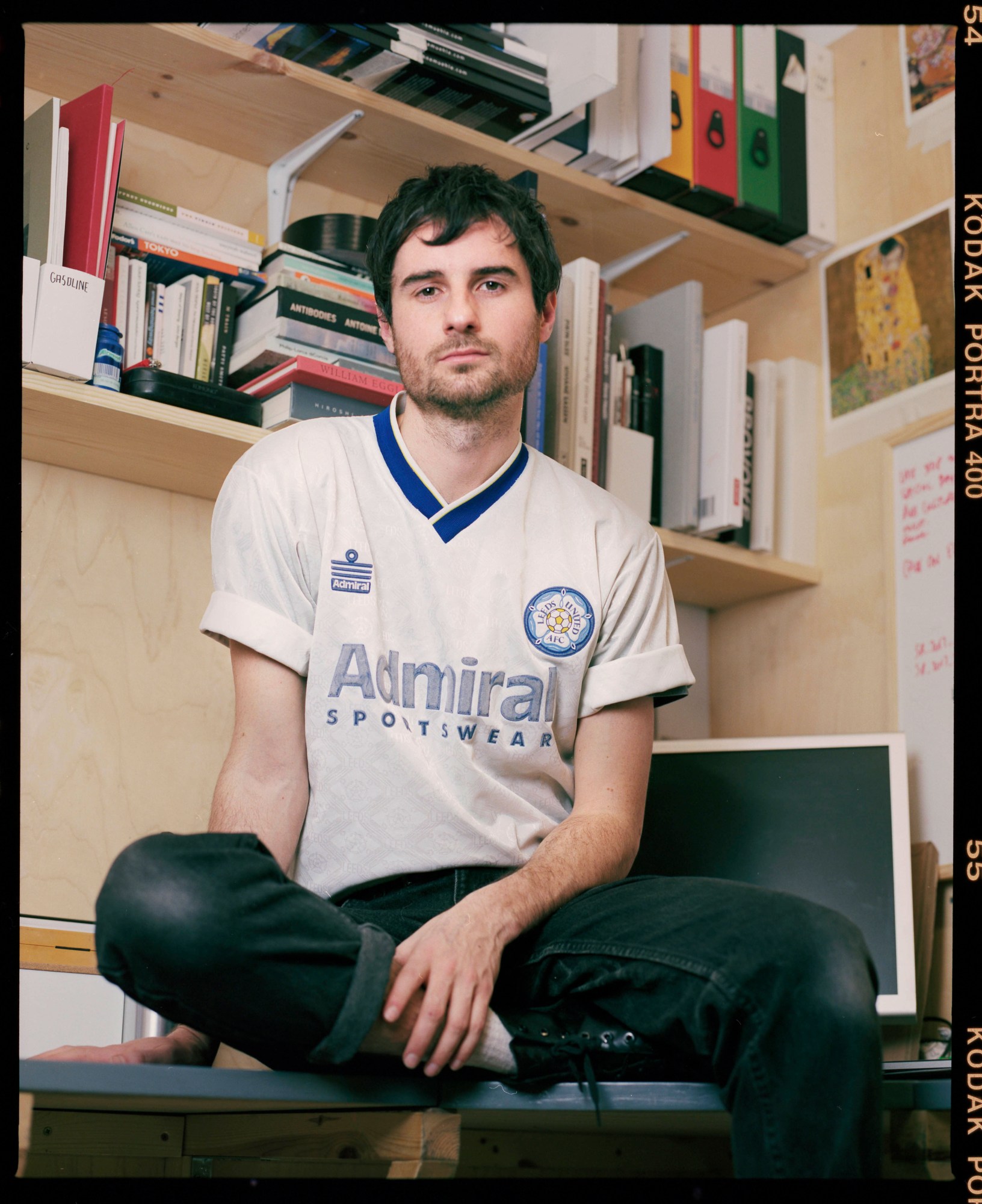

Sam Rock, studio 11

I’m from Harrogate in North Yorkshire. I have a love/hate relationship with the place. So as much as my work is for the love of pictures, it’s more often than not a vessel for my own experience and excitement — an excuse to go places. I hated textbooks, so I chose sport and art. I didn’t start taking photography seriously until about 23 though when I moved to New York after finding a random internship in a photo studio via a Craigslist ad. My training was all working on set and assisting. When I first turned up I still didn’t know what a shutter speed was but some amazing people took me aside and taught me everything from how the camera works, to lighting and general problem solving.

I moved back again to London in September of last year and can honestly say moving into Sarabande has changed everything. Every day there’s a group of passionate artists in one place working tirelessly, but everyone is around to chat and share.

If you want any longevity and self-satisfaction you have to find a way to not do the same thing that we’ve all seen a million times before. I think we’re all getting tired of seeing images. I am. So it has to be something else. If that’s even possible.

Judas Companion, studio 11

I am German and grew up in a small village. My parents are both creative and taught me many things including sewing, knitting, painting, drawing, photographing, printing and woodwork. Most of these techniques are visible in my artworks. They address transformations of identity. I create masks, costumes and wearable sculptures using off-cuts, leftovers and donated materials. I then photograph the pieces while wearing them to create the final work — a masked self-portrait.

I usually like things which go a bit ‘wrong’ — things that fail intentionally and unintentionally. To me it’s interesting when a piece of work reflects the human being as a product of nature. Art is the only part of my life where I don’t have to wish. I make what I want to.

ROBERTS | WOOD, studio 13 and 15

I want my work to make people feel curious. I make clothing created from the point of view of construction, often engineering garments and textiles in unconventional ways — for example, without stitching. I’d say it is somewhere in the middle where art meets science. I started off with a completely different background. I trained as a doctor in Glasgow, then did an MA in Fashion at RCA some years later.

Sarabande is such an amazing thing — having the physical space to create work in a very supportive environment is a rare privilege. The Foundation also takes a very holistic approach when working with the residents here, and there is a brilliant community and network.

Georgia Lucas-Going, studio 14

When someone asks me to describe my work, I say it’s self-taught survival techniques. I got to this point through my parent’s continuous emotional support. I am fortunate to have had my mum and dad (RIP) turn up to weird gigs, be on the front row, take pictures on their phones, help me write applications and not ask me when I’m going to have children or get married. Also down to Sarabande Foundation for funding my studies and studio — I point blank would not have been able to do an MFA, or be sat in this studio writing this, without their support.

There are definite hierarchies in the art world and performance is always bottom of the list. It can take months to perfect a performance, and all my performers with me must be paid also. For example, I can’t afford to split one artist fee with my mother who often works with me, and I especially refuse to not pay her as she has worked hard enough as a black woman.

If you look at my work and feel nothing, I’ve failed.

Credits

Photography Giovanni Corabi