After the Charlie Hebdo massacre, the people took to the streets. After the November attacks, the military did. Public protest gave way to police protection; solidarity became suspicion. A state of emergency was declared, and continues to this day. The City of Lights has never quite been the leafy boulevards, cobbled backstreets, and café culture utopia of the postcards. The segregation of city and suburbs demarcated by the périphérique, the ring road surrounding Paris proper, has long drawn symbolic divisions more intractable than the concrete on which it sits. The suburbs — the banlieues — struggle with crime, gangland tensions, ghettoized migrant populations, and enduring racial and religious tensions born of France’s colonial past. In a city divided, unity has come under threat.

In February 2015, a month after the Charlie Hebdo attacks, Combo the Culture Kidnapper — an acclaimed French street artist — tattooed the word “coexist” on a Parisian wall. The Muslim crescent formed the ‘C’; the Star of David formed the ‘X’; the Christian cross formed the ‘T’. Its call for religious unity and peace provoked the opposite: in a savage attack by four young men, Combo was left beaten, bloodied, and with a dislocated shoulder.

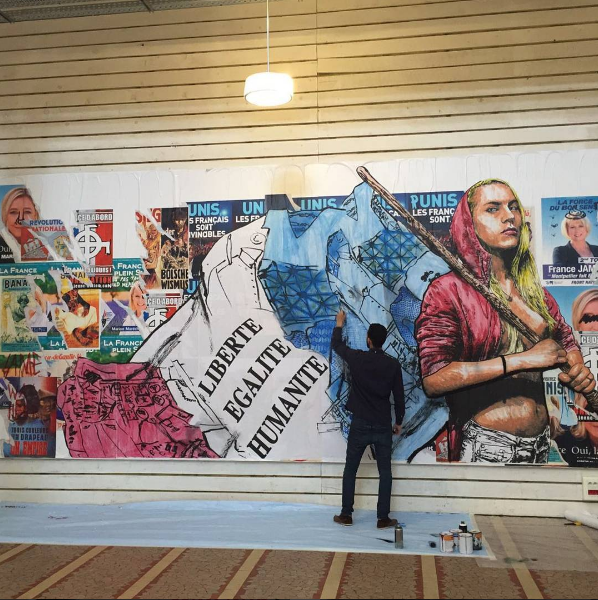

His subsequent exhibition at the prestigious Institut du Monde Arab in Paris, featured a diverse cross-section of his work, from Romantic tableaux depicting drowning migrants to cut-and-paste collages clashing stencilled Muslim youths with hashtags, news clippings, religious imagery, and quotes from literary classics. In exploding the barriers between “high” and “low” culture, offering alternative narratives on real-world events, and exploring the composite nature national and individual identity, Combo forces art to become action.

“We are all different,” he explains, sipping mint tea in a crowded Parisian café, “but I think that’s our common ground: it should be what unites us.” Asked whether he thinks unity is best achieved by doing away with labels of identity, or by accepting and embracing the differences they denote, he opts for the latter. “It’s a question of freedom,” he says, “the freedom to be different.”

Yet identity has long been a vexed question across the world, from digital social justice movements to civil war in the Middle East, and France’s political landscape becoming increasingly polarized along identity-informed lines. Identifying with Arab, French, Jewish, Christian, and Muslim heritage, Combo has felt the rise of the Front National, the French fascist party, particularly acutely. Most worrying, he argues, is the way in which the new wave of nationalism has shifted old battles over nationality on to new grounds over race and religion.

“First, we were Arabs, and now all of a sudden, we’re Muslims,” Combo explains, touching on the idea that while France’s colonial past once made Arabs the Other that white nationalists struggled against, now it is Islam at large.

Outrage is nothing new, however, either from the nationalists who declare him an “anti-white racist” or the conservative Muslims who condemn him for tags such as “Don’t die a virgin, there are terrorists up there waiting for you.” Combo is open about the provocative nature of his work: “Look, if you’re making stuff your grandma says is ‘nice,’ you’re probably doing something wrong,” he says with a smile. From breaking into Chernobyl’s nuclear plant in an attempt to draw attention to French reliance on nuclear power to working in Beirut on Islamist extremism, pushing boundaries, breaking taboos, and posing questions many would rather not answer is precisely what unifies his work.

The global resonance of his work has been amplified in the age of social media. “The hashtag has become as important the wall you’re tagging,” he says, “and as as soon as I mention migrants or Muslims, I know it’s going to take off,” albeit for the wrong reasons. “I don’t make art for social media, that’s boring, but in some ways street art works by the same logic as Twitter,” he adds: “you make phrases that are concise, important, and shareable” and, citing the way Twitter has been used in mass protests all over the world, “both are about hijacking power.”

Asked whether social media has changed the way people interpret his work, and if the new contexts created by sharing and retweeting have threatened the integrity of his work, he is dismissive: “You can’t control what people think of your work, and I don’t try to. It’s my job to pose a question, not to offer a response. If there isn’t dialogue, that’s when problems arise. What I’m doing is starting dialogue, I’m not transmitting truths.”

Dialogue is the watchword of the conversation, recurring again and again, piercing through the machine-gun pace of Combo’s French as something in which he has unshakeable faith. “I have faith in people, faith in intelligence, faith in the idea that we don’t just reject what we don’t understand, but that we start a dialogue,” he explains. “When we do, when we start to open up, beautiful things can be born.”

While such lofty statements risk sounding pretentious in the mouths of most, for Combo, these ideas are more pragmatic than philosophical. This isn’t art for art’s sake: it’s art that demands social change and that, like popping a blister, forces whatever is festering under the surface out into the open. It is unfailingly human, in its content, in its treatment, and in its often collaborative process.

“Art changes things because people change things: art in itself changes nothing, people do,” he explains, “That’s why my art takes place in the street.”

In fact, “it goes beyond art,” he adds: “I work with charities, I attend planning meetings, I sit on panels, I’m involved in creative action. Street art is just one tool. Alongside it, you need forge alliances and new communities with others.” Building coalitions between communities, whether ethnic, religious, geographical, sexual, or political is the only path available in a globalized world. Coexistence isn’t an ideal: it’s a necessity.