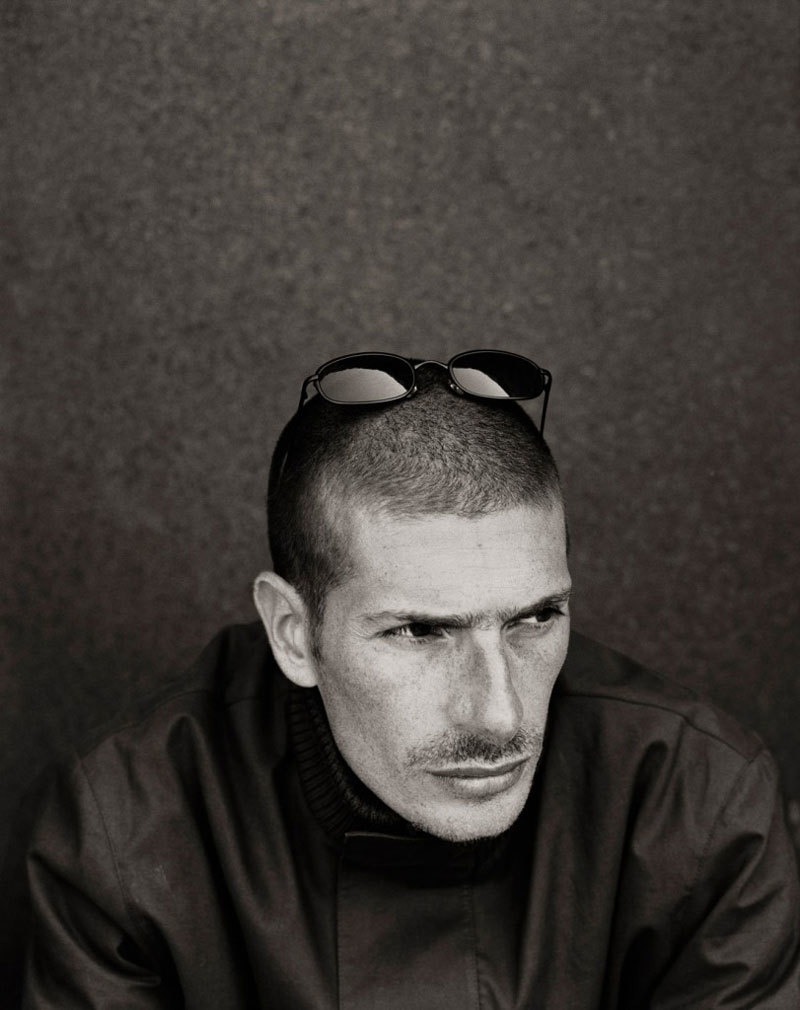

To understand how much of a mark Jonathan Mannion left on the history of hip-hop, look no further than the rappers whose portraits he took over the course of twenty years: Notorious B.I.G., Jay-Z, DMX, Outkast, Kanye West, Eminem, Mos Def, Drake, and Rick Ross. In other words, with a resume like that, the New York-based photographer isn’t concerned about competition. Over the years, he’s become one of the major witnesses to the hip-hop scene, combining memories, anecdotes, and funny stories. Mannion shared some of these moments and recollections with us.

Can you tell us about the moment it became clear that you could make a living off your photography?

First of all, it must be known that I come from a family with an artistic background. Both of my parents are painters, and I studied art at Kenyon College in the U.S.. It was only during the last year of my studies that I started to get seriously interested in photography. I saw a project about the basketball player Ch’e Smith, and the technique really interested me. What’s funny is, that same year, my school gave us the opportunity to take some courses with Richard Avedon. I was there and I learned a ton at that time. I understood that the most important thing was the interaction [between the photographer and] the subject. I also got lucky: A month and a half later, I was employed at Richard’s studio.

Was it at his side that you were able to work with rappers for the first time?

Not really, no. I wasn’t anything more than one of his four assistants at the time. The people who allowed me to work with MCs were Steven Klein and Ben Watts. They made me realize I should concentrate on hip-hop and document it.

Was it easy for you to spend time around rappers when you were just starting out?

Actually, yes. You know, I spent tons of time working, sometimes from 7am to 9pm. When we were finished, I’d follow them out to clubs where I [got to hangout with] artists like Notorious B.I.G. It was a dream for me: I absolutely wanted to be a part of this musical movement, contribute to its development, and document the stories of all its artists.

Were you biased towards portraiture right away?

Let’s just say that I really love the human interaction that portraits entail. You need to talk to the subject a lot; have exchanges, dialogues, et cetera… Without those steps, you’re not going to have anything but a photograph that’s devoid of all meaning. At least that’s what I believe in, and that’s why I’m constantly deep in observation and discussion.

What do you particularly strive to capture? A mood? A way of being?

Basically, I look for the moment where the rapper is totally sure of himself; where he closes his eyes and opens his heart. For me, it’s at that exact moment where I can take the most beautiful photo possible. I want to see how far I can push someone, how far they’re willing to go, whether that’s into joy or introspection. From there, the goal changes constantly — everything depends on the rapper who’s being photographed, what he’s willing [or unwilling] to give me, and the rapport we’re going to establish. I’m not known for taking photographs that are engaged or strange. I’m there to capture a moment.

Over the years, you’ve also been very productive in magazine photoshoots. Is there an exercise you prefer between this and album covers?

For me, the most important thing is to create photos that mark the artist’s career and that fit into the story. The format, in the end, doesn’t matter, although you could think that album covers are more likely to be iconic than photos in magazines. Just think of John Coltrane, or the cover of Bob Marley’s album Kaya. Those photos are almost as mythical as the artists themselves. And it’s a gift for me, for the artists, and for the public to be able to create such moments with the artists.

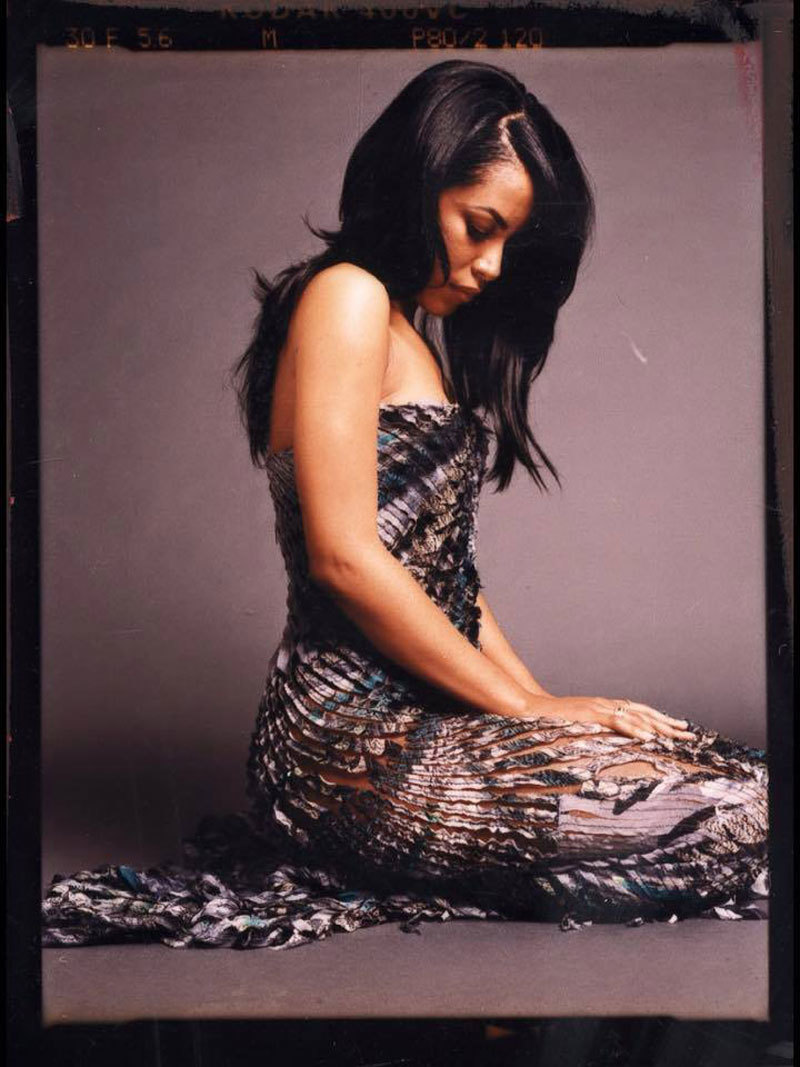

Throughout your career, you had the opportunity to photograph Aaliyah. What can you tell me about her?

I only had one opportunity to work with her, but it was very different than what I’d been experimenting with for a few months. I’d worked with Jay-Z, DMX, Nelly, and Ja Rule, and my approach was inevitably more raw. Then, [I was given the chance to do] something I’d always dreamed of: rendering a sublime woman. And I was happy to do that for the first time with someone as compassionate and kind as Aaliyah. She was very attentive, everyone in her entourage was hyper-attentive to her, and I’ve never found that again with another artist. I’m just sorry that she passed away shortly after our shoot. Nobody could’ve expected that it would be her last session at the time…

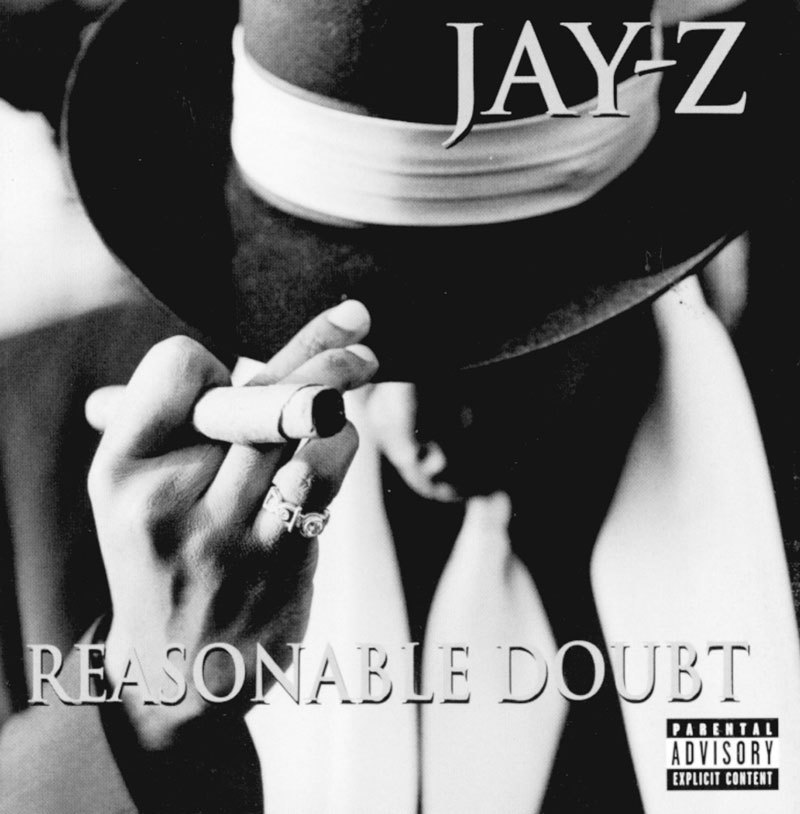

I read that the cover for Jay-Z’s Reasonable Doubt is your favorite cover. Why that one?

Because it was one of the most incredible moments of my career. A moment I’ll never forget. In fact, it was 1996, I was 24 years old, and that album cover marked the beginning of my professional career. I had already photographed well-known guys before, like D’Angelo, Puff Daddy, or Biggie, but it was then that I really had the chance to create something different. His album talked about Brooklyn, about New York, and style and I wanted to translate all of that visually in a single portrait. Moreover, it was my very first album cover. I ended up shooting seven others for Jay-Z, but that one defined my style, my identity.

He didn’t take it badly when you photographed Nas a few years later? When you think about the conflict they’ve had between them for some time, it’s a bit surprising…

I don’t think there was such hatred between the two of them; it was just competition. Like there is throughout all of hip-hop: This musical genre has always brought together artists who want to show just how good they are. There, it was the same. When I worked on the album art for God’s Son, I didn’t have the impression that I was part of the Nas clan or that I betrayed Jay-Z. In any case, these guys are smart enough to know the difference between those two things, especially since I’d already worked with Nas before the cover for God’s Son. For that one, he’d also set aside the “bling bling” aspect of hip-hop for me. So I was able to concentrate entirely on him and understand who he was.

The cover for Flesh of My Flesh, Blood of My Blood is equally as crazy. How did you get the idea to cover DMX with blood?

For a while I’ve thought — and I hope I’m right — that DMX was the rapper who’s the most honest and real. He’s certainly unpredictable and ruthless, but no one can take away his authenticity. I wanted to [build] on that image even though I didn’t have any info about the album beyond its title. Se took a few photos the first day, but he was tired. So we met up again the next day and a discussion [really bloomed] between me and him. The funniest part is that he gave an interview a bit later in which he said the cover was his idea. [It was] a bit like he ended up understanding that it was a good thing for him to appear with all that blood all over him.

Today, as a veteran of the scene, how do you feel when photographing the new generation of rappers?

I love the energy of these guys. Often, they’re excited by the idea of working with me because of what I represent in the history of hip-hop, but I come across guys just as often who know absolutely nothing about the earlier decades, and I think that’s really good. That gives them a rather savage, unpredictable edge — something that lets them kick down doors and make themselves heard. It’s almost a new movement, incredibly bursting with energy. There isn’t, for example, almost a single thing in common between Kendrick Lamar, J. Cole, Danny Brown, or Travis Scott. And nevertheless, they’re all impressive.

Lastly, is there a rapper you’re sorry you never photographed?

Without any hesitation, I’d say 2Pac. He was gone too soon. I actually had the chance to photograph his mother, Afeni Shakur, who told me that her son had adored my personality. You can’t imagine how happy that remark made me.

Credits

Text Maxime Delcourt

Photography Jonathan Mannion

Translation Meredith Balkus