In 2010, Boule Nguyen, a 21-year-old Vietnamese-Canadian, dropped out of school, cashed in his savings, and embarked on a year-long road trip throughout Canada and the United States. Driving non-stop with a car full of Vietnamese clothing samples, he had a simple goal: to build a distribution business from scratch by going city to city, store to store.

A decade later, armed with years of experience winning the trust of brands, Nguyen is flipping the script with his latest, and most ambitious endeavor: There VND Then, a tri-level Saigon concept store centered on importing coveted international brands making their first-ever entrance to Vietnam. Opening in October in the heart of the city’s bustling District 1, There VND Then (the VND stands for Vietnam’s currency, the Vietnamese đồng) will also house an on-site ice cream parlor, barber shop, a rooftop bar and lounge.

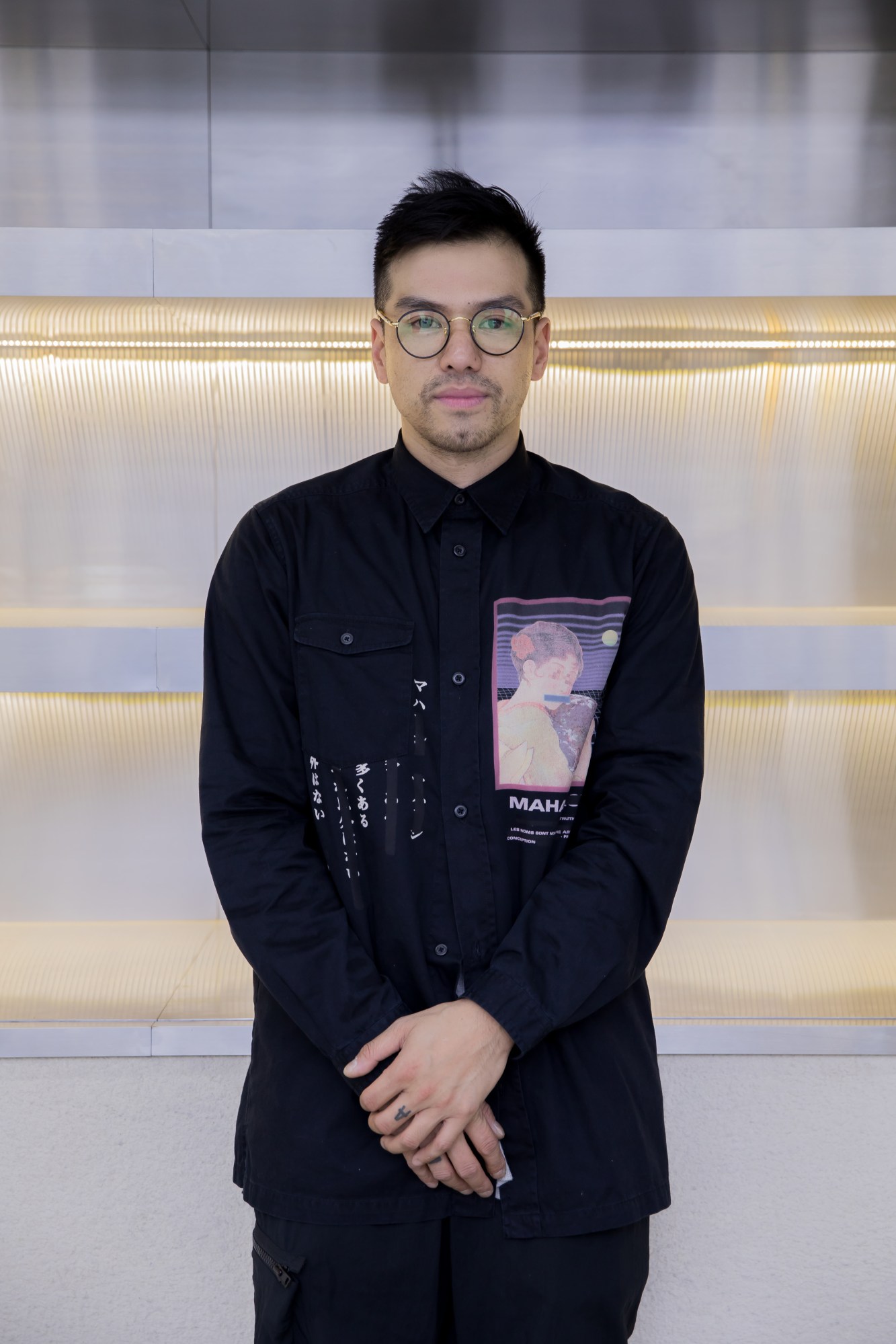

“We’re the first to do what we’re doing in terms of the scale and range of concepts,” says Nguyen, now 34 years old. “I noticed over a decade ago that things were really bubbling in Vietnam, but there were so many barriers from taxes and duties to lack of market maturity. We didn’t just lack resources to open a store like this, we also didn’t have trust from foreign brands. It was like asking someone to hand over their baby.”

Though you’ll still find “Made in Vietnam” on goods from Nike, North Face, Lacoste, and more, decades of explosive economic growth have transformed the country from just a production hub to a legitimate consumer fashion market. And with a powerful middle class hungry to participate in global culture and commerce, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam’s largest city and commercial epicenter, welcomed its first locations of fast-fashion retailers like Zara, H&M, Forever 21 all within the last two years.

Now, the launch of There VND Then signals a watershed moment for Vietnam’s fashion scene, which, like the country, has become increasingly diverse and democratic. There’s a palpable excitement and sense of pride, especially in the creative capital of Saigon, that Vietnam could become a key player in fashion in the digital age—whether that means bringing Western and East Asian goods to the local marketplace or exporting homegrown talent like designers Nguyen Cong Tri and Phuong My, both of whom presented collections at New York Fashion Week fall/winter 2019.

Nguyen, a Montreal native whose family returned to Vietnam when he was a teenager, says he wanted to target a very specific gap in the market for mid-range and premium apparel brands, especially those rooted in streetwear. Thus far, there’ve been just a few high-end boutiques like Runway selling exclusively high-fashion brands like Givenchy and Saint Laurent. Meanwhile, the nascent scene of local upstarts, while innovative and ambitious in design, can’t meet consumer demands for internationally-recognized labels.

To purchase a Nike sneaker or Stussy t-shirt, then, Vietnamese consumers would either have to absorb the item’s exorbitant fees or rely on what Nguyen describes as intricate “networks of air stewardesses and tourists hand-carrying goods back to Vietnam.” Either way, they were shelling out more for the exact same item.

“Nike produces tons of its shoes in Vietnam, but they don’t sell many styles here,” Nguyen explains. “It’s not fair for Vietnamese consumers to have to pay 20 to 40 percent more than everyone else. At our boutique, our goal is to always hit MSRP—sometimes we have to take a hit, but as we build our relationships, we can tighten up and cut down on shipping costs. We’re fighting an old mentality.”

There VND Then’s offerings—from Heron Preston and Common Projects to Yeezy and Thrasher—speak largely to the tastes of Vietnam’s booming youth population—over 70 percent of the country is younger than 35 years old, according to the World Bank—who leverage social media to embrace global sensibilities not just in fashion, but in food, art, and music. Just a few weeks before the store opened, Vietnam’s reigning prince of pop Son-Tung MTP released a single featuring Snoop Dogg along with a music video starring American singer Madison Beer.

“Nowadays, brands are not just targeting middle-aged consumers—the Vietnamese youth are playing an important part in creating the trends,” says Vinh Khuat, fashion editor and stylist at Harper’s Bazaar Vietnam. “Vietnamese fashion is undergoing a phase of globalization and rejuvenation. We’re seeing more and more streetwear-oriented events and shows here. So while a franchising concept store [like There VND Then] might not be so foreign to those who’ve travelled to other cities, the Vietnamese market is very much in need of this kind of outlet.”

But importing outside brands is just the start of Nguyen’s vision to connect Vietnam with the rest of the world. Next, he hopes to engage local brands and talents, many of whom he says have paved the way in terms of identifying and catering to the youth demographic. Nguyen cites key players like Floralpunk, a women’s boutique founded by his friend, the Vietnamese-German influencer Julia Doan, as well as 42 The Hood, a collective of fashion enthusiasts that includes designers, models, stylists, and photographers—many of which produce their own brands.

“There are tons of amazing, hardworking designers here, but the trajectory is limited,” Nguyen explains. “Once you establish yourself in Vietnam, there’s no support to grow and support the brand internationally. I have so much appreciation for the people who are creating, or making art and music, without resources you take for granted in North America. And I want them to one day sit in our store next to the brands they covet. It would be a monumental thing for me to achieve and for them to see—hopefully, we’ll smash that ceiling.”

With increased access to digital media—the number of smartphone users in Vietnam reached 28.77 million in 2017—there’s plenty of potential out there for an upstart Vietnamese brand to take the world stage. Just take Julia Doan’s work with Floralpunk, which she started as a personal style blog while still a 21-year-old in college. In 2013, she launched it as a full-fledged brand selling original women’s clothing. Now the owner of three successful brick-and-mortar locations in Saigon, Doan says she chose to launch Floralpunk in Vietnam because of low production costs, but also increased demand among consumers.

“Vietnam is a very young market with growing spending power, which is a great opportunity for a fashion business,” she explains, “The demand for Floralpunk in Vietnam was much higher than in Germany because five years ago, there weren’t many shopping destinations for millennials especially in Saigon. That’s why I decided to move the whole business to Vietnam and and grew it mostly through content and influencer marketing.”

Doan says she believes its essential for Vietnam’s fashion leaders and brand owners to stand together and collaborate, a sentiment echoed by Ryan Son Hoang, a 25-year-old entrepreneur and founding member of 42 The Hood. As Hoang explains, the group developed its name after its members—each with their own brand—decided to come together and rent out an entire apartment building one unit and floor at a time. The building’s address? 42 Ton That Thiep.

While each brand still operates out of its own space at that building, Hoang changed the game in 2016 when he opened The New Playground in Saigon, a boutique selling only local brands, including many of those from his 42 The Hood cohorts like The Beuter and Mamavirus. At the end of last month, he opened a second location called The New District in Hanoi. “Almost all the brands we sell are created by young people,” says Hoang. “We aren’t just selling clothes—we’re selling inspiration for the community. And young Vietnamese people are slowly learning how to embrace their style.”

It’s a hopeful message that Hoang echoes in There VND Then’s first big editorial campaign, for which he served as a creative director. Spotlighting the boutique’s inaugural offerings from the likes of South Korea’s IISE and New York’s Maharishi, the futuristic, alien-themed video and photo series touts fearless individuality and expression.

Such empowerment is likewise a guiding principle for Nguyen, whose eyes light up when he talks about his hopes for Vietnam’s future. Soon, he says, they’ll launch a creative workspace called Collab to help cultivate new talent and offer a forum for sharing ideas. He calls it a network of creatives—advised by a council that includes designer Cong Tri—that’ll fill a much needed void for Vietnamese youth who want to build a creative business: “In countries like Vietnam, it’s necessary because we don’t have community centers for youth—we need these kinds of spaces.”

It’s this work that makes There VND Then truly a concept for the people of Vietnam—and the future. “I’m well aware that fashion is not the most important thing in the world, but it’s a means to express yourself—a platform to pursue your passion,” says Nguyen. “With the coming Fourth Industrial Revolution, everything will be automated and jobs will become obsolete—all we will have then is our creativity and that cannot be emulated. We need to prepare the next generation and give them something they can hold onto.”