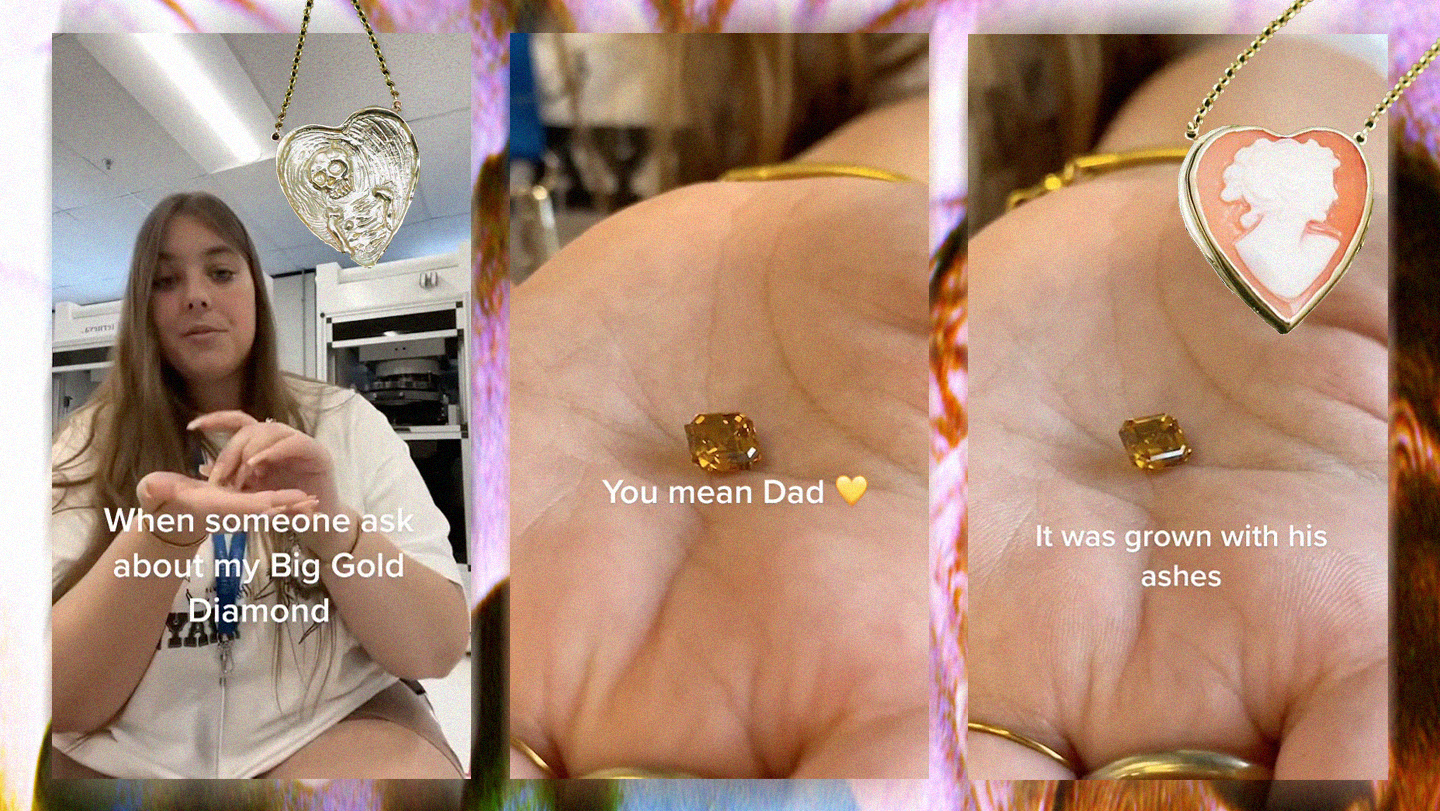

Not to be too bleak, but… if you lost someone you loved, would you turn their cremains into a diamond ring? Or wear them around your neck in a pendant? Could you? Some people can. Tear-inducing clips of mourners flexing their memorial diamonds are trending all over TikTok, as more and more people are wearing their grief out in public, dangling it from their necks or wrists like a fashion statement. And, while it might seem morbid, it can only be a good thing.

For those who’ve never browsed a funeral home catalogue: memorial jewellery is a piece of bling you wear to commemorate a dead loved one. It can be subtle; the delicate heart-shaped pendant one mourner filled with her mom’s ash. It can be overtly gothic; the ash-filled casket-shaped rings Margaret Cross made after losing her best friend. It doesn’t even have to contain human remains. “Losing that would feel too weighty and my dad wanted his ashes to be scattered,” explains mourner Ton Stevens. Instead, Tom wears his dad’s guitar pick as a pendant, silver-plated and engraved with his dad’s fingerprint. But if TikTok’s discovery page is anything to go by, most mourners today opt for memorial diamonds. They’re grown using human remains and even Kris Jenner considered turning herself into one.

Most of TikTok’s memorial diamonds are from Eterneva. Its co-founder, Adelle Archer, owns two delicate memorial rings herself. Respectively set with a black and champagne diamond, she lovingly calls them her “Tracey-rings”, as they’re grown from Tracey Kaufman’s cremains. “She was my close friend and business mentor and we wanted to start a lab-grown diamond company,” shares Archer. Tracey’s passing led Adelle to have a conversation with a diamond scientist around what to do with her ashes. This, in turn, prompted the start of Eterneva.

Although Eterneva as a company is relatively young, memorial jewellery itself has been around for centuries — it was hugely popular with the Victorians — and the ashes-to-diamond option having been available since the early 2000s. So why are people only getting hyped up now? Well, chances are, you think of grief as a trauma to be processed, which you’d do by “letting go” of the deceased. At least, that was the popular opinion. According to Dr Candi Cann, who investigated the therapeutic value of memorial diamonds, that’s also why therapists traditionally disapproved of memorial bling. How could you let go of someone while wearing their cremains around your finger?

“But now, conversations around mental health are being destigmatised and Covid-19 has brought death close to home,” says Adelle Archer. As a result, we’re accepting grief as something more public and permanent. At Eterneva, Archer and her colleagues call this: “the sixth stage of grief”. Dr Cann, too, agrees that grief isn’t really about letting go, but about finding new ways to connect with the deceased. Memorial jewellery, then, has massive therapeutic value.

“We’re a much more mobile society today and we don’t want to leave our people behind,” adds Adelle. Assuming you don’t want to haul a body around Little Miss Sunshine-style, memorial bling is a wearable and socially acceptable way of keeping your deceased physically close, wherever you go. Lots of Adelle’s clients use jewellery to include their deceased in life’s important milestones: “They commission a diamond before their wedding day, so their mom can be there or their dad can walk them down the aisle.” But many also wear their jewellery daily, in which case a pendant or ring can help them reconnect to memories during the minutiae of life. That’s when loss makes itself most known anyways: when someone who used to be a part of your day-to-day is suddenly absent from it. As she speaks, Adelle toys with the diamond pendant around her neck, which she reveals to be her grandmother. “And I can see my Tracey-rings when I’m typing,” she continues. “It’s a comfort to have them with you, not just as a thought, but as a physical piece.”

When someone dies, they’re essentially reduced to memories, grief, maybe a small digital footprint. These are very immaterial things, so connecting to the deceased turns into a game of memory. Is something real if it only exists in your mind? Perhaps that’s why most memorial jewellery contains human remains (or in Stevens’s case, a fingerprint). It’s a physical manifestation of an abstract thing; forensic evidence that this person existed, that your memories are legit and so is the pain you feel over losing them. In her paper, Dr Cann phrases it better: “Grief, in its most basic description, is the experience of absence. The diamond allows a marking of absence through presence.”

People usually tiptoe around topics like death, grief and the obvious absence of a loved one. But given statement rings often draw attention, memorial jewellery works like a conversation prompt. This can be cathartic for the bereaved, but it also helps break some of the stigma around grief as a whole. Another client, Liz Pires, lost both her children to an opiate overdose and enlisted Eterneva for the memorial diamonds. “She has two huge diamonds set in a gorgeous ring and now she’s dedicated her life to attacking the opiate epidemic,” says Adelle. “Usually, people would avoid the topic. But that ring is such a statement piece. She gets asked about it daily and she can talk about her kids.”

Like an ash-filled urn, memorial jewellery is a material reminder of the deceased. But urns signify death. So people tend to hide and ignore them. Has anyone ever complimented someone’s urn? Jewellery, on the other hand, is glossy and lustrous and treasured. “Unlike an urn, when people looked at their memorial diamond ring, they were reminded of the deceased’s vibrance, brilliance and spirit. It was a reminder of how they were in life,” says Adelle. As such, memorial jewellery is both physical and allegorical – body and metaphor. It’s forensic evidence, conversation-starting fashion piece and a memento all at once. Reassuringly for the bereaved, it’s also permanent. Unlike life, it won’t perish; unlike an urn full of ashes, it can happily be passed down through generations; unlike memories, it never fades. Or, in the famous words of copywriter Mary Frances Gerety: “A diamond is forever.”